Responsible Boating Protects Coral Reefs

Abstract

Florida’s Coral Reef is the largest in the continental United States. It sustains tourism and jobs, particularly in southeast Florida. With coastal populations continuously growing, it is imperative that boat operators are aware of this precious natural resource, and steps that can be taken to avoid physical contact that causes long-term damage to this slow-growing system. This publication is intended to serve the recreational boating community.

Florida is often referred to as the boating capital of the nation, with more than 961,000 registered vessels (Florida Highway and Motor Vehicles 2019). Florida’s numerous natural resources such as mangroves, seagrasses, estuaries and coral reefs are a major draw to resident and visiting boaters alike. Outdoor activities associated with boating, such as birding, fishing, swimming, snorkeling, and diving, contribute to the state’s economy.

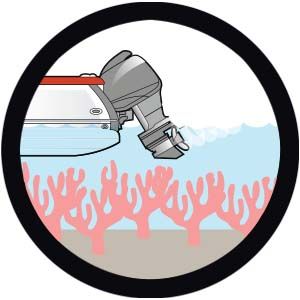

However, increased traffic on the water can bring potential risks, particularly to sensitive ocean bottom habitats such as coral reefs and seagrasses. This publication discusses how new and seasoned boaters can minimize harm to Florida's coral reefs by taking a few simple precautions. Responsible boating will not only help protect the only living barrier reef system in the continental United States, it will also help prevent costly damage to boats.

Credit: National Park Service

Coral Reefs Are Living Organisms

Often mistaken for rocks, corals are living organisms that are closely related to jellyfish and anemones. Individual coral animals are called polyps, and multiple polyps form coral colonies. Many species of coral colonies grow closely together to form coral reefs, which are delicate and complex systems that make up only one percent of the entire ocean floor (Patterson & Lohr 2016). Coral reefs develop in areas with very specific conditions: appropriate levels of sunlight and salinity, a solid base for the coral animals to colonize, clear water, regular wave action, and warm water.

Credit: Kara Wall

Healthy Coral Reef Communities Are Valuable

Coral reefs provide the first line of defense for coastal communities during major storm or weather events, reducing storm surge and flooding (The Nature Conservancy and Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact 2015). Even though they occupy a tiny percentage of the ocean floor, coral reefs support almost one third of the world's marine fish species (Rinkevich 2008). Moreover, coral reefs, particularly those in Southeast Florida, are world-renowned tourist attractions for the fishing, snorkeling, and diving opportunities they provide.

Florida’s Coral Reef is Threatened

Beginning 70 miles from Key West at the Dry Tortugas, Florida’s Coral Reef (FCR) runs approximately 350 linear miles north to the St. Lucie Inlet in Martin County. The FRT hosts an ecosystem that is home to more than 600 species of fish, more than 40 stony corals, 37 species of soft corals, 70 species of sponges, and 600 species of invertebrates. Seven of these reef-building stony coral species carry “threatened” status under the Endangered Species Act.

Many factors threaten the health and integrity of coral reefs, including but not limited to coastal development, marine debris, physical damage, overfishing of marine life, poor water quality, warming ocean temperatures, changing pH levels, marine debris, and disease (Burke et al. 2011).

Grounding Vessels on Coral Reefs and Dropping Anchor Over Them Damages Fragile Coral

Vessel groundings can obliterate an entire area of reef, flattening it into a rubble field, or "pavement" area. Anchors dropped onto reefs can dislodge or break corals apart. Corals are slow-growing; depending on the species, some only grow 1 to 7 inches per year. This means recovery from either of these phenomena can be a slow process, if it happens at all.

The Florida Coral Reef Protection Act was created to increase protection of coral reef resources on sovereign submerged lands. Sovereign submerged lands include, but are not limited to, tidal lands, sandbars, shallow banks, and lands waterward of the ordinary or mean high water line, beneath navigable fresh water or beneath tidally influenced waters (https://floridadep.gov/water/submerged-lands-environmental-resources-coordination/content/sovereign-submerged-lands-ssl) off the coasts of Martin, Palm Beach, Broward, Miami-Dade and Monroe Counties (Florida’s Coral Reef Protection Act 2009). This act makes it illegal to anchor on or otherwise damage coral reefs along the Florida Reef Tract. For more information visit: https://floridadep.gov/rcp/coral/content/reef-injury-prevention-and-response-program.

Credit: Ana Zangroniz

What can you do to become a responsible boater?

The good news is that physical damage to coral reefs from boating is 100 percent preventable and simply requires practicing responsible boating.

Here is how to be a safe boater:

Avoid

- Check tides and weather before going out.

- Use polarized sunglasses when boating to scout for shallow areas where reefs may be close to the surface and avoid those areas.

- Confirm that you are over sand before you drop anchor.

- Familiarize yourself with reef locations using local navigational charts.

- Tie up to mooring buoys instead of anchoring. For mooring buoy locations in southeast Florida, please visit these websites:

- Southeast Florida Mooring Buoys, (Martin County south to Miami-Dade County) https://floridadep.gov/sites/default/files/2019-03%20Mooring%20Buoy%20Brochure_Updated.pdf

- Biscayne National Park Mooring Buoy Locations https://www.nps.gov/bisc/planyourvisit/mooring-buoy-locations.htm

- Buoys within Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary http://floridakeys.noaa.gov/mbuoy/buoymap.html

- Always anchor safely and securely in sand, not on coral reef. To find a sand spot to drop your anchor in, download and use the Southeast Florida Reef locator app: https://floridadep.gov/rcp/coral/content/reef-injury-prevention-and-response-program

- Take a boating safety class. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission provides an extensive list of classroom course and online providers at this website: https://myfwc.com/boating/safety-education/courses/

Trim

- If you do run aground, do not try to use your motor to power off of the reef. Using your motor over the reef will almost certainly cause additional damage.

- Turn off your motor.

- Trim (tilt) your motor up.

- If possible, take note of your GPS location for reference.

Call

- If you happen to get stuck on a reef, stay put and contact a towing or salvage company for assistance.

- Be sure to notify the appropriate agency if any coral reef damage occurs.

- In the Florida Keys: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: 888-404-FWCC.

- North of the Florida Keys: Florida Department of Environmental Protection's Coral Reef Conservation Program, 866-770-7335; also online at www.SEAFAN.net.

Remember These Rhymes to Avoid Damaging Sensitive Bottom Habitats

Brown, brown, run aground: Avoid brown areas. Brown indicates reefs or seagrass beds are close to the surface.

White, white, you just might: Use caution. Sandbars and rubble areas may be much shallower than they appear.

Green, green, nice and clean: Green waters are generally safe for shallow-draft boats; larger, deeper-draft vessels should exercise caution.

Blue, blue, cruise on through: Clear sailing in deep-water areas.

Conclusion

Florida’s Coral Reef hosts a diverse, environmentally productive and economically dynamic ecosystem. The reefs generate an estimated 70,000 jobs and $6.3 billion in sales and income (Johns et al., 2001). This system faces many threats, both locally and globally. Physical damage related to boating is completely preventable and this publication offers several practices that are easy to adopt. Responsible boating will make a difference in protecting this valuable resource for future generations.

References

Burke, L, Reytar, K., Spalding, M., Perry, A. 2011. "Reefs at Risk Revisited." World Resources Institute.

Florida's Coral Reef Protection Act. Florida Statute 403.93345.

Florida Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles. 2019. https://www.flhsmv.gov/pdf/vessels/vesselstats2019.pdf. Accessed on February 16, 2021

Johns, G., Leeworthy, V. Bell, F. Bonn, M. 2001. Socioeconomic Study of Reefs in Southeast Florida. Report by Hazen and Sawyer under contract to Broward County, Florida.

The Nature Conservancy and Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact. 2015. "Nature-Based Coastal Defenses in Southeast Florida."

Patterson, J., Lohr, K. 2016. FA199. Coral Reef Conservation Strategies for Everyone. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fa199

Rinkevich, B. 2008. "Management of Coral Reefs: We Have Gone Wrong When Neglecting Active Restoration." Marine Pollution Bulletin, Volume 56, 1821–1824

Sovereignty Submerged Lands. https://floridadep.gov/water/submerged-lands-environmental-resources-coordination/content/sovereign-submerged-lands-ssl Accessed on October 18, 2017