A Homeowner's Guide to the Living Shoreline Permit Exemption Part 2: United States Army Corps of Engineers

Background

"Living shoreline" is a catch-all phrase that describes a riparian area managed with restoration techniques that use natural material such as oyster reef, mangroves, and marsh grasses to stabilize the area, prevent erosion, and protect property. Living shorelines typically involve construction or placement of materials within navigable waters of the United States. Therefore, the US Army Corps of Engineers (also known as the Corps) regulates the installation of living shorelines through a permitting process. This process ensures that project activities do not conflict with the public interest and defines actions that must be taken when a project is expected to have negative impacts. In the interest of streamlining the approval process for environmentally beneficial projects such as living shorelines, the Corps has created a permit mechanism called Nationwide 54 that can fast-track permitting for small-scale living shoreline projects that meet certain criteria. See Appendix for the list of criteria a living shoreline must meet to qualify for a Nationwide 54 permit. The Corps process is similar but not identical to the Florida statewide exemption available through the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Similar to DEP, Corps staff are able to conduct pre-application meetings to help ensure the permitting process goes smoothly for you. To request a pre-application meeting with the Corps, use the form provided in the Appendix.

Credit: NOAA

Part 1 of this guide covers the DEP permit exemption and Submerged Lands Authorization process. If you have already navigated the DEP application process and received an official Verification of Exemption letter, Submerged Lands Authorization, and if your DEP office also issued you federal authorization through the State Programmatic General Permit (SPGP), then no further action is required before proceeding with your living shoreline project. However, if you did not receive a federal (Corps) authorization through DEP, which is typically the case, then you must submit a separate permit application to the Corps.

You probably already have all of the required information at your fingertips. The Corps nationwide permit application is short and free to submit, and it requires information very similar to that requested by DEP. Remember, Corps staff at your regional regulatory office are willing to meet with you on site or talk with you over the phone about your project during a "pre-application" meeting.

This guide provides example text for each application section that covers all of the bases but is still no longer than a paragraph for each section. You can adapt the example text to your needs. Site drawings can be hand drawn or easily produced using widely available software that you probably already have on your computer. As long as you have all the information and drawings handy, completing and submitting the form should take roughly 30-60 minutes. As stated above, this information is very similar to that requested by DEP, and thus there will be overlap between the information below and the information provided in Part 1 of this guide.

What This Guide Covers

This guide is a companion to the document A Homeowner’s Guide to the Living Shoreline Permit Exemption Part 1: Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Consult Part 1 to learn about how to apply for the living shoreline permit exemption and Submerged Lands Authorization available through DEP. This guide (Part 2) covers the federal permit application managed by the Corps, a step which may not be necessary if the DEP issued both a federal and state authorization for your project.

In Florida, permit applications are managed by the Jacksonville District of the Corps through a series of regional offices. Visit the office locations page for a map of the counties in Florida covered by each regional office. You will need to complete the ENG FORM 6082 (Nationwide Permit Pre-Construction Notification (PCN) form) linked below. Complete it electronically or by hand and submit it by mail or email to the contacts listed on the regional offices webpage along with the required project drawings. There is no fee to submit this form. This guide will help you complete and submit the form correctly.

Steps to complete the Corps' permit application form are presented below, in a page-by-page fashion. You may also find value in the application instructions and checklist available as a PDF from the USACE. The checklist applies to a different but very similar form (ENG FORM 4345) so the box numbers shown on the checklist may not match exactly. Nevertheless, the checklist may still be helpful as the most of the same elements are required for the Nationwide Permit form.

The glossary provides definitions for several key terms you will need to understand when preparing your application.

After You Submit

Processing and approval of a permit application to the Corps typically takes about 60 days for a complete application. If you fail to include any of the necessary information, a Corps officer will contact you with a request to provide the information or elaborate on certain aspects of the project. Failure to provide all of the necessary information will result in delays to your project approval.

PDF Form

The permit application form (ENG FORM 6082) can be downloaded by right clicking the “Nationwide Permit Pre-Construction Notification” link found on the Corps’ Obtain a Permit webpage and then clicking “Save link as…” to download a copy to your computer. You may fill out this form electronically, or you may print it and complete it by hand. The steps below will guide you through each page of the form. There are also additional instructions on the last three pages of the form itself. The final section shows examples of the vicinity map and drawings you are required to submit.

Page 1: On this page, you will need to provide general information such as your contact information project title, and (optional) the contact information of your agent, if any, and your signature authorizing the agent. Usually, the agent would be a contractor you are working with, but it is likely you will not have an agent if you plan to complete the project yourself. You can designate any project name or title that you wish but make it descriptive. We suggest you include the term “living shoreline” to quickly orient the regulatory official to what you are proposing.

Page 2: On this page, you must provide the waterbody name, information about your property (location, tax parcel ID, and GPS coordinates), driving directions to your project site starting from a known landmark, such as an interstate exit, nearby town or city, or major highway intersection. You must also provide information about the project, including the nature of activity, project purpose, and the Nationwide permit number you intend to use. It is important that you are thorough and provide enough information for the Corps to assess whether or not your activity is allowable. Incomplete information in any of the sections on this or other pages will result in delays. You may append as many extra sheets as you need, with the block number of the question noted at the top of the extra sheet. If you first completed the Request for Verification of Exemption form for DEP, you will be able to re-use much of the descriptive text you already gathered.

- Some specific tips and guidance for Page 2:

- The name of the waterbody should be name of the estuary, bay, river, stream, marsh, or creek where you will build your living shoreline project.

- You can locate the coordinates for your property using free tools such as Google Earth® or https://www.latlong.net/. Important: When entering coordinates for your project, make sure you provide them in the requested format (DD = decimal degrees). If the tool you use to locate the coordinates does not provide them in DD format, then you can use a free online coordinate converter such as http://www.earthpoint.us/Convert.aspx.

- Find your tax parcel ID number in any of several ways: Check your most recent property tax bill. Visit the website of your local tax assessor. Call your local tax assessor’s office and request the information.

- For Block 18, most living shorelines would qualify under Nationwide Permit 54. If you are applying for a living shoreline, enter NWP 54 into Block 18.

- Blocks 19 to 22 ask for information about the specifics of your proposed activity (living shoreline). See below for examples of how to fill out Blocks 19 to 22 for three different scenarios: planting only, breakwater/sill only, and breakwater/sill with planting. Feel free to adapt the example text below for your own use. Note: the figures given in the text below are only examples. You should consult with a local expert to determine the appropriate plant species, oyster reef heights, and materials to use in your project. Useful resources can be found at www.floridalivingshorelines.com, www.flseagrant.org, or your local UF/IFAS Extension office.

- Block 23. You may need to fill this out if your project includes activities other than your living shoreline. For most simple, small-scale living shorelines projects this will not be the case. If you are only applying for living shoreline activities, enter “None”.

- Block 24. If the number of acres you entered in Box 22 is less than 0.1, this section is not applicable. However, for most simple, small-scale living shorelines projects that are built on eroding or degraded shorelines, there will actually be a creation of wetlands rather than impacts to wetlands. Use this space to explain that your project is creating or restoring wetlands rather than impacting them. If the number of acres you entered in Box 22 is higher than 0.1, then describe your project in additional detail using the instructions on page 5 of the form for guidance.

Example Text:

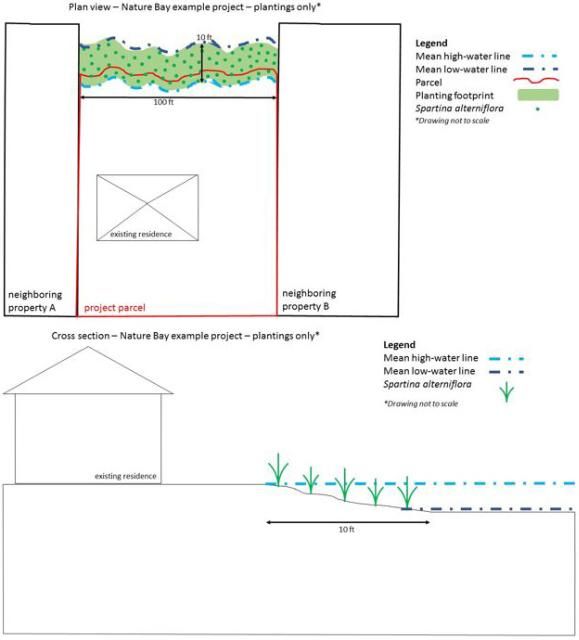

Plantings only—

Block 19: I plan to install native marsh vegetation along the shoreline of my backyard (100 linear feet). I will obtain smooth cord grass (Spartina alterniflora) from a local nursery and plant it in the intertidal zone along the shoreline. I will plant clumps of plants on 2-foot centers along a 10-foot-wide section of shoreline (5 rows of plants that will extend no more than 10 feet waterward of the mean high water line).

Block 20: Planting will occur at low tide over the course of 2 to 3 days. Plants will be monitored for survival, and any plants that die within the first three months may be replaced with fresh specimens (also obtained from a nursery). All exotic vegetation will be removed from the site prior to project activities. No fill will be added other than soil imported with nursery grown transplants. There will not be any discharge associated with the project other than that imported with nursery-grown plants. Plants must be installed to mitigate erosion. Plantings will occur at low tide and cease when the tide covers the work area. There will not be any sediment releases or turbidity associated with planting at low tide because resuspension of sediments will be impossible without water present. Sediments loosened by digging holes for plants will be packed back into place immediately upon placing the plant in the hole.

Block 21: My property, located in Nature Bay, Florida, has been experiencing erosion over the past few years, likely because of seawalls on either side of my property. In order to slow and reverse this erosion, I am proposing to install a living shoreline and I would like to begin construction by [provide your proposed timeline].

Breakwater/sill only—

Block 19: I plan to install an oyster reef breakwater in front of my property (90 linear feet) in Nature Bay, Florida, to protect my shoreline from further erosion. I will deploy oyster shell contained within heavy-duty plastic mesh bags or gabions (pprox.. 4 to 5 gal. of shell per bag/gabion). The bags/gabions will be deployed in the intertidal zone with the waterward toe occurring no more than 10 feet seaward of the mean high-water line. Bags/gabions will be stacked on top of each other in alternating orientations in order to achieve a height of 2 feet, allowing them to reach the ideal zone for oyster recruitment and growth. We will use stable, natural materials (bagged oyster shell/seasoned oyster shell contained in gabions with 2.5-inch openings) to construct the breakwater and the bags/gabions will be secured using rebar stakes.

Block 20. Gabions/bags will be deployed at low tide over the course of 1 to 2 weeks. The breakwater will not encroach upon and will not be placed anywhere within 3 feet of any submerged or emergent vegetation. There are no seagrass meadows in the vicinity of my project. The waterward toe of the breakwater will not be placed more than 10 feet waterward of the mean high tide line. Shell material will be sourced from Nature Bay Shell Recycling that has seasoned the shells outside in the sun for at least 6 months. Additionally, the breakwater will have a 6-foot wide gap every 47 feet along the shoreline to allow for water and wildlife passage. Oyster shell bags/gabions will be deployed using hand carry methods and, thus, no equipment with the potential to damage the shoreline will be used. The breakwater will be installed at low tide, and all activity will cease when the tide covers the work area. There will not be any sediment releases or turbidity associated with deploying oyster bags/gabions at low tide because resuspension of sediments will be impossible without water present at the site.

Block 21. There are seawalls on either side of my property that are causing erosion of my property. I am proposing to install a living shoreline consisting of oyster reef breakwaters to interrupt wave energy and reduce erosion of my property. In order to mitigate erosional forces of waves and currents, it is necessary to deploy a breakwater/sill structure. I have selected oyster shell bags and gabions as the appropriate material to place in front of my property to achieve erosion control.

Breakwater/sill and plantings—

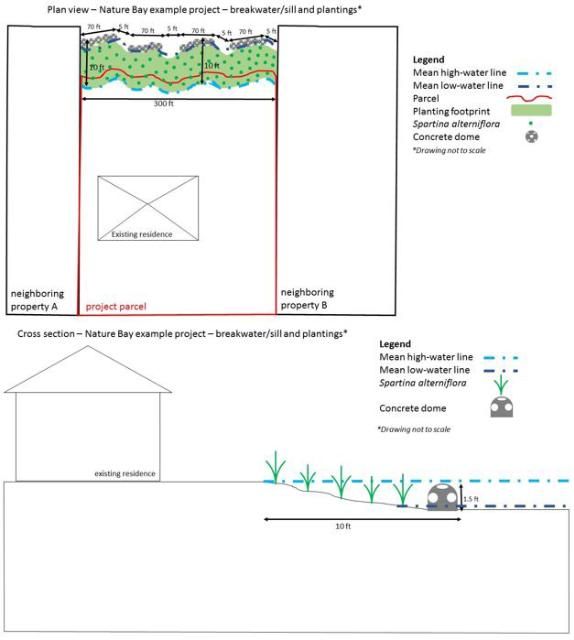

Block 19. I plan to install a concrete dome breakwater in front of my property on Nature Bay, Florida, to protect my shoreline (300 linear feet) from further erosion.. Concrete domes will be deployed by professional contractors in the intertidal zone, with the waterward toe of the concrete domes occurring no more than 10 feet seaward of the mean high-water line. Concrete domes will be approximately 1.5 feet tall and 2 feet wide, placing a high percentage of the concrete dome surface area within the ideal zone for oyster recruitment and growth. Concrete domes will be deployed continuously regardless of tidal stage using hand-carry/float methods over the course of 1 week. After installation of concrete domes, the shoreline behind the breakwater will be planted with native vegetation to further reduce erosion and increase habitat value. I will obtain smooth cord grass (Spartina alterniflora) from a local nursery and plant clumps of plants on 2-foot centers behind the 10-foot-wide section of shoreline protected by the concrete domes (5 rows of plants that will extend no more than 10 feet waterward of the mean high tide line).

Block 20. Planting will occur at low tide over the course of 2 to 3 days. Plants will be monitored for survival, and any plants that die within the first three months may be replaced with fresh specimens (also obtained from a nursery). All exotic vegetation will be removed from the site prior to project activities. Plantings will extend no more than 10 feet seaward of the mean high tide line and the inner toe of the breakwater will likewise extend no further than this line. No fill will be added other than soil imported with nursery-grown transplants. The breakwater will not encroach upon and will not be placed anywhere within 3 feet of any existing submerged or emergent native vegetation. The coastal area behind my home is a mudflat, and there are no seagrass meadows within 0.5 mile of my home. The breakwater will be constructed of stable materials (concrete domes) and will be secured using fiberglass stakes. Rows of concrete domes will have 5-foot-wide gaps every 70 feet along the shoreline to allow for water and wildlife passage. There will be four, 70-foot-long breakwaters with 5-foot gaps in between each. Concrete domes will be deployed by professional contractors using hand-carry and float methods, and, thus, no equipment with the potential to damage the shoreline will be used. Plantings will occur at low tide and cease when the tide covers the work area. There will not be any sediment releases or turbidity associated with planting at low tide because resuspension of sediments will be impossible without water present. Concrete domes will be deployed using hand-carry and/or float methods, and very limited resuspension of sediments will occur with this method (walking across the site). No heavy equipment or tools (other than a hammer to drive in a narrow fiberglass rod) will be used in this project. The disturbance to sediments at the site will be minimal.

Block 21. There are seawalls on either side of my property that are causing erosion of my property. I am proposing to install a living shoreline consisting of oyster reef breakwaters to interrupt wave energy and reduce erosion of my property. To mitigate erosional forces of waves and currents, it is necessary to deploy a breakwater structure with plants behind it. I have selected Spartina alterniflora and concrete domes as the appropriate material to place in front of my property to achieve erosion control.

Block 21 supplemental text. See below for some additional descriptive text that can be added to Block 21 (purpose). Feel free to adapt the example text below for your own use, but keep in mind that you should consult with an expert for help choosing the best method for you.

Example text:

Plantings only—This project aims to create/restore wetlands in order to benefit from the ecological functions. By installing native vegetation, this project will benefit the local ecosystem as well as my personal property.

Breakwater/sill only—The breakwater will be constructed in the intertidal zone in water deeper than mangroves and marsh grass can survive. The primary purpose of the project is to mitigate erosion along the shoreline adjacent to my property. The project will create habitat for oyster recruitment and overall will benefit the local ecosystem.

Breakwater/sill and plantings—This project aims to create/restore wetlands in order to benefit from the ecological functions. By installing native vegetation and oyster recruitment substrate, this project will benefit the local ecosystem.Block 22 Tips. Unless you are installing plants only, you will need to fill out the wetland impact section (Block 22). In the eyes of the Corps, materials such as oyster bags, gabions, cinder blocks, and rocks are considered fill material. Therefore, you will need to fill out this section if your project incorporates oyster shells, concrete domes, gabions, coir logs, sand fill or other structural elements placed in the water. Feel free to adapt the example text below for your own use, but keep in mind that you should consult with an expert for help choosing the best method for you.

Plantings only

Block 22- Acres. N/A; wetlands will be created, not filled in.

Block 22 Linear Feet. N/A; wetlands will be created, not filled in.

Block 22 Cubic Yards. N/A; wetlands will be created, not filled in.

Breakwater/sill only

Block 22 Acres. 0.005*

*Acres may be estimated by:

- calculating the length of the project in feet, subtracting any mandatory gaps (90 feet minus one 6-foot gap = 84 feet in this example);

- taking the width of the structure (3 ft in this example);

- multiplying length by width to obtain square feet; and

- dividing the square feet by 43,560 to get the value in acres.

Block 22 Linear Feet. 90

Block 22 Cubic Yards. Type: bagged oyster shell; amount in cubic yards: 18.7**

- **Amount in cubic yards can be estimated by:calculating the length of the project in feet, subtracting any mandatory gaps (90 feet minus 6-foot gap = 84 feet in this example);

- estimating the height and width in feet (2 and 3 feet, respectively, in this example);

- multiplying the three numbers together (length × width × height) to yield the volume in cubic ft (504 ft in this example); and

- dividing by 27 to yield the value in cubic yards (18.7 cu yd in this example).

Breakwater/sill and plantings

Block 22 Acres. 0.01* .

*See above for instructions on how to estimate acres.

Block 22 Linear Feet. 300

Block 22 Cubic Yards. Type: concrete domes; amount in cubic yards: 31.1**

**See above for instructions on how to estimate cubic yards

Page 3: On this page, you must provide background information about any work that has already been completed (usually none for a living shoreline) and information about endangered species, historic resources, or wild and scenic rivers that might be affected by the project. Finally, you need to sign and date the permit application. See the office locations webpage for information about where to submit your permit application form. Select the regional office that serves your county, and either email or mail the application and all drawings and illustraions (see below) to the appropriate location.

Some specific tips and guidance for Page 3:

- Block 26. Fill in the names of any endangered species that occur in your project area. The National Endangered Species Act habitat mapping tool is a good resource for figuring out which species to list. This mapping tool shows all of the designated critical habitat for endangered species. If your project will occur within critical habitat, you must list the species name in this block.

- Block 27. List any historic properties that might be affected. For most living shoreline projects, this will not apply. Check the National Register of Historic Places map if you are unsure.

- Block 28. If your project will occur within the Loxahatchee River or Wekiva River, list that information here. If you are unsure or would like additional information, see https://www.rivers.gov/florida.php.

- Block 29. This block applies if your project will permanently alter or occupy a federal civil project managed by the Corps. Usually, this will not apply to small scale living shoreline projects.

- Block 30. In this block, you can provide additional information to support your application. For Nationwide Permit 54, it helps the Corps if you also provide information any state or local permits or authorizations you have already received in this section. This particularly helps with the additional requirements such as water quality certification and Coastal Zone Management Act concurrence (see instructions on Page 6 for more information).

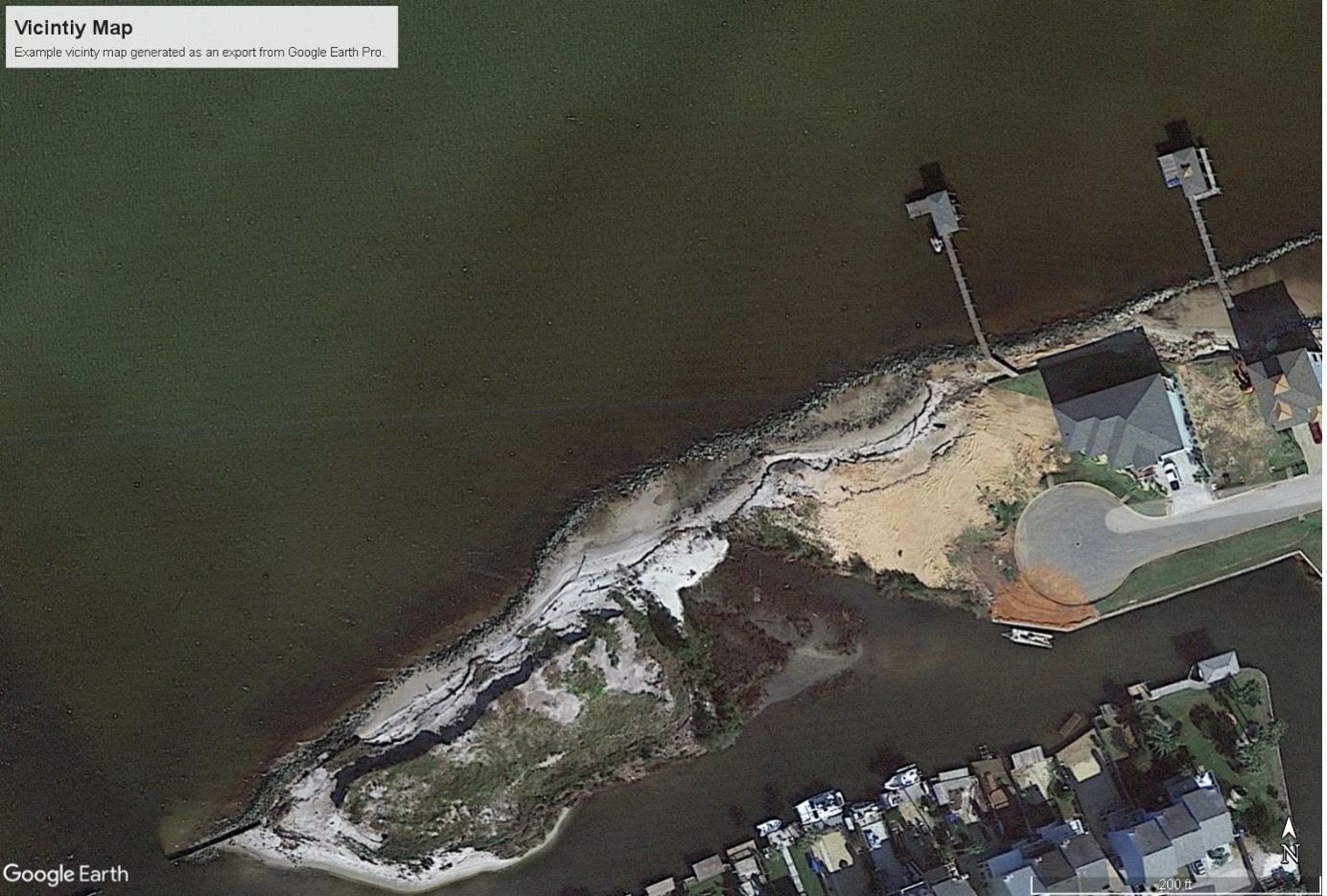

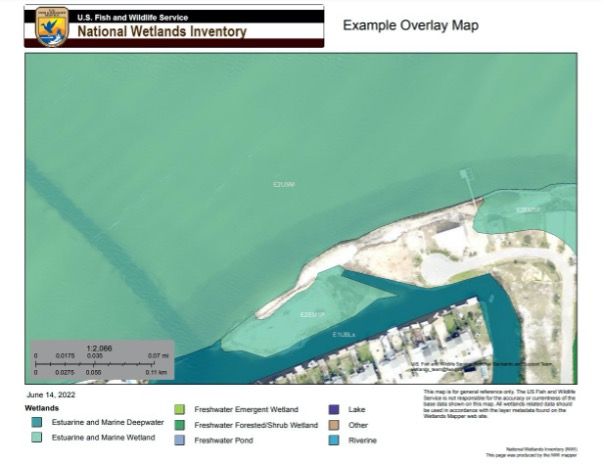

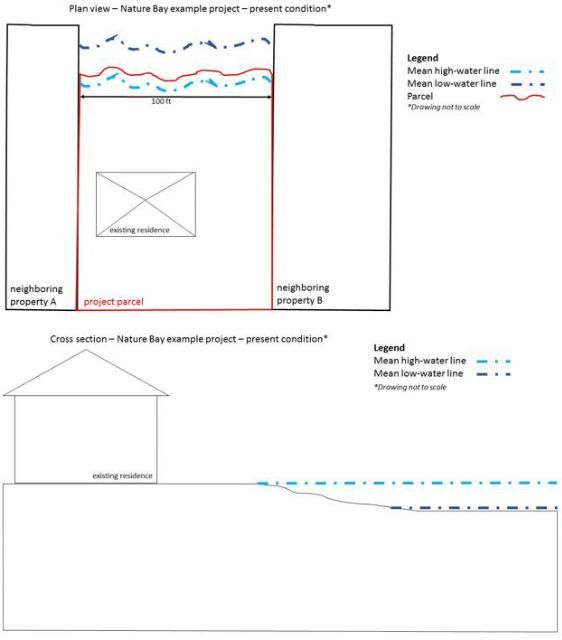

Drawings and Illustrations: You must include 1) a vicinity map with enough detail to allow someone to find the project, 2) an overlay map showing the a delineation of all wetlands and surface waters on site, and 3) overhead (plan) view and cross-section drawings of a) the present site condition, and b) your project when you submit the ENG 6082 form. See below for examples of acceptable plan view and cross-section drawings.

The overlay map can be produced using publicly available data from the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Access the USFWS National Wetlands Inventory Wetland Mapper Tool and zoom in to your site location. Once your entire project area is in view, use the “PRINT” feature in the top right to export your map. Give your map a name in the dialog box that pops up and then click the green Print button. A legend and title will automatically be generated in the print file. Your map will show up under “Print Jobs” in the dialog box and then you can download the exported map as a PDF to include with your application.

The detailed set of drawings should depict both the current site conditions and the project in cross section and in overhead (plan) view. These drawings must show:

- The location of the mean high-water and mean low-water lines;

- The linear distance along the shoreline covered by the project;

- The linear distance the project will extend into the water, as measured from the mean high-water line;

- Planned spots for placement of plants, breakwater/sill elements, and gaps in breakwaters with dimensions such as linear distances and/or heights noted;

- Existing structures;

- Any nearby habitats and the approximate location of the shoreline of neighboring properties;

- An arrow indicating the direction of North;

- The locations of the cross-section drawing(s) shown on the plan view drawing.

You may produce these drawings yourself either by hand or using simple shape illustrations available in computer programs such as Microsoft PowerPoint. Drawings need not be to scale, as long as this is noted on the drawing. It may be helpful to include extra photographs of the site to aid in your explanation. Of course, you always have the option of hiring a contractor who will provide the drawings as part of the contract, but this is typically not necessary for simple projects. To give you an idea of the level of detail required, see the example cross section and plan view drawings below. We have provided an example for each of the three basic project types mentioned above: plantings only, breakwater/sill only, breakwater/sill and plantings.

Vicinity Map

Overlay map

Credit: undefined

Present condition

Plantings only

Breakwater/sill only

Conclusion

This guide covered the process for applying for a streamlined living shoreline permit (Nationwide 54) from the US Army Corps of Engineers. We covered background information about living shoreline permits, provided sample text for several sections of the Corps application, and outlined the process for creating acceptable project drawings for small-scale projects. We gave instructions for submitting the permit application to the Corps. If you provide complete and correct information on the application, within 60 days you should receive confirmation that your project is approved. The Corps will send you a permit letter with attachments. The letter will notify you that your project has been approved and outline instructions for communicating with the Corps regarding construction activities. Be sure to thoroughly read the letter you receive and make note of any additional permits or follow-up information you may need to provide. To avoid fines, fees, or other regulatory action, make sure you construct your project exactly as planned. If you find you need to make changes to your project, notify the Corps before you make them to verify the changes will not jeopardize your approval.

Helpful Resources

Florida Sea Grant Living Shorelines: https://www.flseagrant.org/?s=living+shoreline

Florida Living Shorelines Project Example Page: http://floridalivingshorelines.com/florida-sampler/

Florida Living Shorelines Resource Database: http://floridalivingshorelines.com/resources/

NOAA Understanding Living Shorelines: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/insight/understanding-living-shorelines

NOAA Climate Resilience Toolkit: https://toolkit.climate.gov/topics/coastal-flood-risk/coastal-erosion

NOAA Living Shorelines: https://www.habitatblueprint.noaa.gov/living-shorelines/

NOAA Tools for Planning: https://www.habitatblueprint.noaa.gov/living-shorelines/applying-science/tools-for-planning/

NOAA Guidance and Training: https://www.habitatblueprint.noaa.gov/living-shorelines/applying-science/guidance/

NOAA Consultations and Permits: https://www.habitatblueprint.noaa.gov/living-shorelines/consultations-permitting/

StormSmartCoasts - Erosion Control Structures: http://ms.stormsmart.org/before/mitigation/only-as-a-last-resort-flood-and-erosion-control-structures/

StormSmartCoasts - Non-structural Shore Protection: http://ms.stormsmart.org/before/mitigation/non-structural-shore-protection/

US Army Corps of Engineers Jacksonville District Permitting Source Book: https://www.saj.usace.army.mil/Missions/Regulatory/Source-Book/

Contact information for professionals working on living shorelines in your region can be found at http://floridalivingshorelines.com/contacts/ or your local UF/IFAS Extension Office.

Glossary of Terms

Breakwater—generally, a structure built to provide a barrier to or protection from waves. There are many definitions of the term "breakwater," but usually they are offshore structures designed to reduce incoming wave energy, resulting in calmer water between the shoreline and the structure. Oyster reef breakwaters are built at intertidal heights (submerged at high tide) out of materials conducive to colonization by oysters. In Florida, breakwaters built as part of small-scale living shorelines are only exempt from permitting if they are built no higher than the mean high-water line.

Clean oyster shell—Oyster shell used in living shorelines must be clean of disease and pests in order to be a safe material. There are several sources of clean oyster shell, including recycled shell and fossilized shell, from both non-profit and for-profit organizations. Recycled shell that comes from seafood restaurants must be cured outdoors in a sunny area in piles that are routinely turned for at least 6 months. This prevents the spread of oyster pests and disease. The DEP will usually request information about the specific source of the shell when reviewing an application for Verification of Exemption.

Coir logs—biodegradable logs made from coconut fiber often used in construction of sills in living shorelines.

Concrete dome—concrete forms in the shape of domes. This method of oyster reef construction uses molded, pre-cast concrete forms designed to mimic the attributes of the natural three-dimensional structure of oyster reefs. In some cases, the concrete mixture is fortified with an additive to increase oyster recruitment. There are many commercially available forms.

Cross-section drawing—a depiction of your living shoreline project in cross-section, including information about the slope of the shoreline, approximate mean low-water and mean high-water locations, breakwater heights, spacing of plants, location of existing structures, etc.

Emergent vegetation—wetland plants that are rooted with stiff or firm stems, like cattails. Emergent vegetation usually stands above the water surface, but in some cases can be found submerged during occasional periods of high water. Lily pads and many marsh plants are considered emergent plants.

Erosion—process of sediment being carried away from an area. In coastal environments, the major driving processes of erosion are storms, flooding, wave action, sea level rise, and human activities (i.e., boating, seawall construction, development). Erosion is a natural process in coastal ecosystems, but it becomes an issue when homes and other infrastructure are threatened.

Exotic/invasive species—exotic species are those that are not native to an ecosystem. Invasive species are those that are not native to an ecosystem and cause harm to native species and/or ecosystem functions. Examples of invasive plants in Florida's coastal environments include the invasive Brazilian pepper and Phragmites australis marsh grass. You can check to see if a plant is invasive at https://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu/assessments/.

Intertidal zone—the area that is above water at low tide and under water at high tide (in other words, the area between tide marks), commonly inhabited by oysters.

Gabion—a wire framework container that provides a structured foundation for shell material. Made of a material similar to chain-link fencing, gabions are filled with shells and ballast, then stacked and wired together to construct sturdy, three-dimensional structures.

Marsh vegetation—herbaceous (non-woody) plants that thrive in wetlands. A wetland is an area that is inundated or saturated by surface water or ground water at a frequency and a duration sufficient to support, under normal circumstances, a prevalence of vegetation typically adapted for life in saturated soils. Most living shorelines deal with the creation of low and middle marsh that are more frequently inundated by water than the upper marsh zone.

Mean high-water line (MHWL)—the line on a chart or map that represents the intersection of the land with the water surface at the elevation of mean high water (the average of all the high water heights observed over the period of time defined by the National Tidal Datum Epoch). Homeowners can roughly estimate the MHWL using physical markers like stakes or flags placed at high tide over a period of weeks, or by observing and marking the location of at the tidal wrack lines (line formed by debris washing up at high tide), or by looking at aerial photos. DEP suggests erring on the upland side instead of the waterward side when approximating the MHWL. The MHWL can also be determined by a licensed surveyor.

Mean low-water line (MLWL)—the line on a chart or map that represents the intersection of the land with the water surface at the elevation of mean low water (the average of all the low water heights observed in the period of time defined by the National Tidal Datum Epoch). Homeowners can roughly estimate the MLWL using physical markers like stakes or flags placed at low tide over a period of weeks or by observing aerial photos. The MLWL can also be determined by a licensed surveyor.

National Tidal Datum Epoch—the specific 19-year period adopted by the National Ocean Service as the official time segment over which tide observations are taken and reduced to obtain mean values (e.g., mean lower low water, etc.) for tidal datums. It is necessary to standardize mean tide level in this way because of periodic and apparent trends in sea level.

Native vegetation—plants that occur naturally in an area.

Ordinary high-water line (OHWL)—the analogue of the mean high-water line for freshwater bodies such as rivers, streams, and lakes. The OHWL is typically determined by using the best evidence available, including water marks, soil and vegetation indicators, and historical aerial photos.

Oyster-recruitment substrate—structure such as shell or concrete deployed in the intertidal zone of the coast for the purpose of increasing oyster attachment opportunities.

Plan-view drawing—a depiction of your living shoreline project from an overhead perspective, including information about the approximate mean low-water and mean high-water lines, breakwater/sill placement and spacing, spacing of plants, location of existing structures, location of parcel boundaries, etc.

Sill—material deployed at the base (toe) of a vegetated zone for the purpose of reinforcing and protecting the area from moderate energy waves and currents. Sills can be constructed out of materials such as shell, concrete, or coconut fiber logs. Sills differ from breakwaters in that they are constructed directly adjacent to the vegetated area.

Submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV)—Grasses that grow to—but not above— the surface of shallow water. This includes seagrasses and freshwater aquatic grasses.

Turbidity—the measure of suspended solids, which influences water clarity. Murky water has high turbidity.

Waterward toe—the bottom-most portion of the offshore side of a structure such as a sill or breakwater.

Sources

Federal Register, Vol. 86, No. 245, December 27, 2021

Florida Administrative Code 62-330.051(12)(e)

Florida Master Naturalist Program—Coastal Systems Manual

Florida Master Naturalist Program—Coastal Shoreline Restoration Manual

https://aquaplant.tamu.edu/plant-identification/category-emergent-plants/

https://chesapeakebay.noaa.gov/submerged-aquatic-vegetation/submerged-aquatic-vegetation

https://shoreline.noaa.gov/glossary.html

https://toolkit.climate.gov/topics/coastal-flood-risk/coastal-erosion

Appendix

Source: Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 245 / Monday, December 27, 2021

Nationwide Permit 54. Living Shorelines.

Structures and work in navigable waters of the United States and discharges of dredged or fill material into waters of the United States for the construction and maintenance of living shorelines to stabilize banks and shores in coastal waters, which includes the Great Lakes, along shores with small fetch and gentle slopes that are subject to low- to mid-energy waves. A living shoreline has a footprint that is made up mostly of native material. It incorporates vegetation or other living, natural ‘‘soft’’ elements alone or in combination with some type of harder shoreline structure (e.g., oyster or mussel reefs or rock sills) for added protection and stability.

Living shorelines should maintain the natural continuity of the land-water interface, and retain or enhance shoreline ecological processes. Living shorelines must have a substantial biological component, either tidal or lacustrine fringe wetlands or oyster or mussel reef structures. The following conditions must be met:

(a) The structures and fill area, including sand fills, sills, breakwaters, or reefs, cannot extend into the waterbody more than 30 feet from the mean low water line in tidal waters or the ordinary high water mark in the Great Lakes, unless the district engineer waives this criterion by making a written determination concluding that the activity will result in no more than minimal adverse environmental effects;

(b) The activity is no more than 500 feet in length along the bank, unless the district engineer waives this criterion by making a written determination concluding that the activity will result in no more than minimal adverse environmental effects;

(c) Coir logs, coir mats, stone, native oyster shell, native wood debris, and other structural materials must be adequately anchored, of sufficient weight, or installed in a manner that prevents relocation in most wave action or water flow conditions, except for extremely severe storms;

(d) For living shorelines consisting of tidal or lacustrine fringe wetlands, native plants appropriate for current site conditions, including salinity and elevation, must be used if the site is planted by the permittee;

(e) Discharges of dredged or fill material into waters of the United States, and oyster or mussel reef structures in navigable waters, must be the minimum necessary for the establishment and maintenance of the living shoreline;

(f) If sills, breakwaters, or other structures must be constructed to protect fringe wetlands for the living shoreline, those structures must be the minimum size necessary to protect those fringe wetlands;

(g) The activity must be designed, constructed, and maintained so that it has no more than minimal adverse effects on water movement between the waterbody and the shore and the movement of aquatic organisms between the waterbody and the shore; and

(h) The living shoreline must be properly maintained, which may require periodic repair of sills, breakwaters, or reefs, or replacing sand fills after severe storms or erosion events. Vegetation may be replanted to maintain the living shoreline. This NWP authorizes those maintenance and repair activities, including any minor deviations necessary to address changing environmental conditions.

This NWP does not authorize beach nourishment or land reclamation activities.

Notification: The permittee must submit a pre-construction notification to the district engineer prior to commencing the construction of the living shoreline. (See general condition 32.) The pre-construction notification must include a delineation of special aquatic sites (see paragraph (b)(4) of general condition 32). Pre-construction notification is not required for maintenance and repair activities for living shorelines unless required by applicable NWP general conditions or regional conditions. (Authorities: Sections 10 and 404)

Note: In waters outside of coastal waters, nature-based bank stabilization techniques, such as bioengineering and vegetative stabilization, may be authorized by NWP 13.

You can download the APPLICATION MEETING REQUEST FORM here: https://uflorida-my.sharepoint.com/:w:/g/personal/savanna_barry_ufl_edu/ERjiTm92GxVLodcnGMF6KMMBD-heHKyR276gdquVqPIK5Q?e=y7lYd3