Melon Thrips, Thrips palmi Karny (Insecta: Thysanoptera: Thripidae)

The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The melon thrips, Thrips palmi Karny, is a major pest of vegetables and some other important crops.

Distribution

In recent years, melon thrips has spread from Southeast Asia to most of the rest of Asia, and to many Pacific Ocean islands, North Africa, Australia, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. In the United States it was first observed in Hawaii in 1982, Puerto Rico in 1986, and Florida in 1990. It has the potential to infest greenhouse crops widely, but under field conditions its distribution likely will be limited to tropical areas. In Florida, so far, it is a field pest only south of Orlando.

- Asia: Bangladesh, Brunei, China (numerous provinces, including Hong Kong), India (numerous states), Indonesia (Java, Sumatra), Korea (North and South), Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand

- Africa: Mauritius, Nigeria, Reunion, Sudan

- Caribbean: throughout

- North America: United States (Florida and Hawaii)

- Oceania: American Samoa, Australia (Queensland, Northern Territory, Western Australia), Federated States of Micronesia, French Polynesia, Guam, New Caledonia, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, and others

- South America: Brazil, Columbia, French Guiana, Venezuela

(CABI 1998).

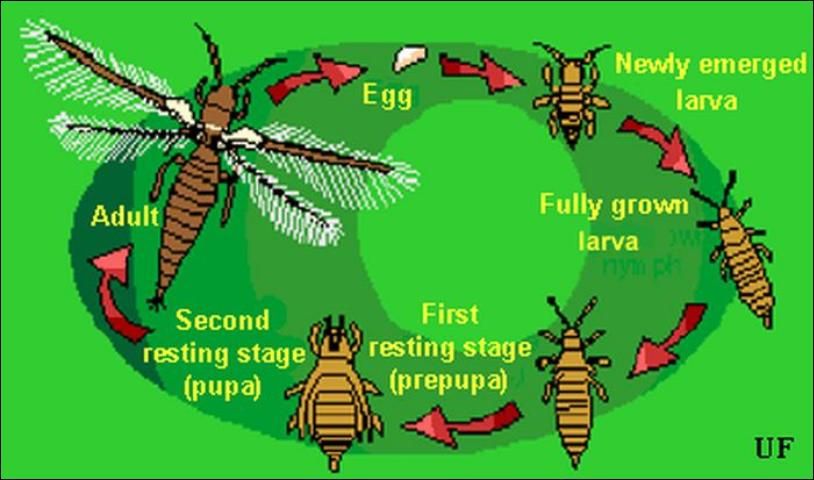

Description and Life Cycle

A complete generation may be completed in about 20 days at 30°C (86°F), but it is lengthened to 80 days when the insects are cultured at 15°C (59°F). Melon thrips are able to multiply during any season that crops are cultivated but are favored by warm weather. When crops mature, their suitability for thrips declines, so this thrips growth rate diminishes even in the presence of warm weather. In southern Florida, they are damaging on both autumn and spring vegetable crops (Seal and Baranowski 1992; Frantz et al. 1995). In Hawaii, they also become numerous on vegetables during the summer growing season (Johnson 1986).

Eggs

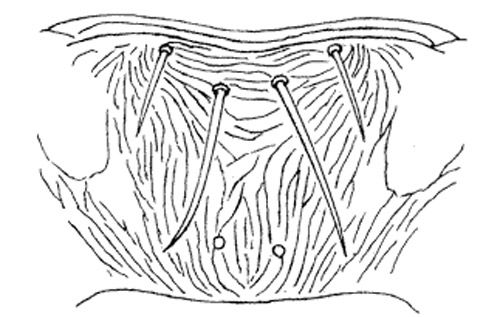

Eggs are deposited in leaf tissue, in a slit cut by the female. One end of the egg protrudes slightly. The egg is colorless to pale white in color, and bean-shaped in form. Duration of the egg stage is about 16 days at 15°C (59°F), 7.5 days at 26°C (78.8°F), and 4.3 days at 32°C (89.6°F).

Larvae

The larvae resemble the adults in general body form though they lack wings and are smaller. There are two instars during the larval period. Larvae feed in groups, particularly along the leaf midrib and veins, and usually on older leaves. Larval development time is determined principally by the suitability of temperature, but host plant quality also has an influence. Larvae require about 14, 5, and 4 days to complete their development at 15°C, 26°C, and 32°C (59°F, 78.8°F, and 89.6°F), respectively. At the completion of the larval instars the insect usually descends to the soil or leaf litter where it constructs a small earthen chamber for a pupation site.

Pupa

There are two instars during the "pupal" period. The prepupal instar is nearly inactive, and the pupal instar is inactive. Both instars are nonfeeding stages. The prepupae and pupae resemble the adults and larvae in form, except that they possess wing pads. The wing pads of the pupae are longer than that of the prepupae. The combined prepupal and pupal development time is about 12, 4, and 3 days at 15°C, 26°C, and 32°C (59°F, 78.8°F, and 89.6°F), respectively.

Adult

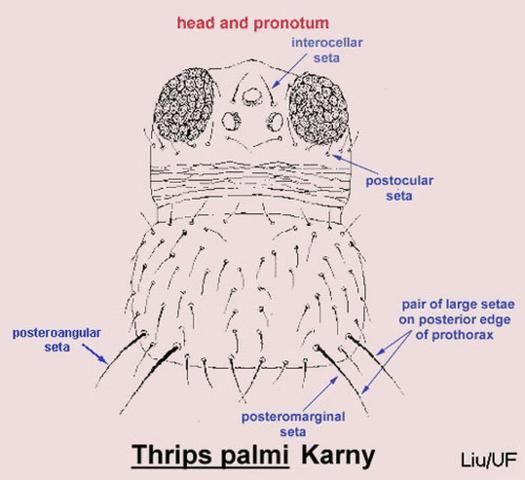

Adults are pale yellow or whitish in color, but with numerous dark setae on the body. A black line, resulting from the juncture of the wings, runs along the back of the body. The slender fringed wings are pale. The hairs or fringe on the anterior edge of the wing are considerably shorter than those on the posterior edge. They measure 0.8 to 1.0 mm (< 1/16 in) in body length, with females averaging slightly larger than males. Unlike the larval stage, the adults tend to feed on young growth, and so are found on new leaves. Adult longevity is 10 to 30 days for females and 7 to 20 days for males. Development time varies with temperature, with mean values of about 20, 17, and 12 days at 15°C, 26°C, and 32°C (59°F, 78.8°F, and 89.6°F), respectively. Females produce up to about 200 eggs, but average about 50 per female. Both mated and virgin females deposit eggs.

Credit: University of Florida

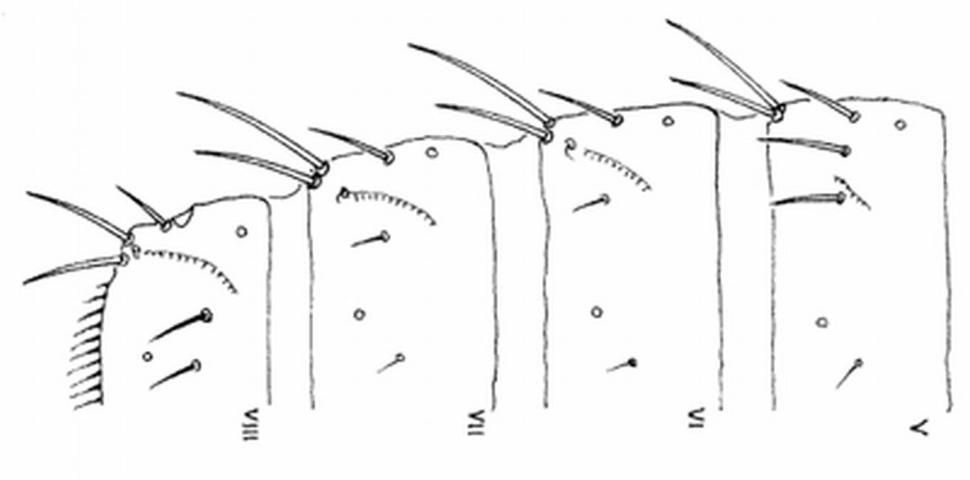

Careful examination is required to distinguish melon thrips from other common species. The Frankliniella species are easily separated because their antennae consist of eight segments, whereas in Thrips species there are seven antennal segments. To distinguish melon thrips from onion thrips, Thrips tabaci Lindeman, it is helpful to examine the ocelli (simple eyes). There are three ocelli on the top of the head, in a triangular formation. A pair of setae are located near this triangular formation, but unlike the arrangement found in onion thrips, the setae do not originate within the triangle. Also, the ocelli bear red pigment in melon thrips whereas they are grayish in onion thrips. In general, the basic body color of adult melon thrips is yellow, but in onion thrips it is yellowish gray to brown.

Credit: T.X. Liu, Texas A&M

The most complete summary of melon thrips biology and management is presented in Girling (1992). Developmental biology is given by Tsai et al. (1995) and field biology by Kawai (1990). Keys for identification of common thrips were presented by Palmer et al. (1989) and Oetting et al. (1993). However, an additional species, Frankliniella schultzei (Trybom), has recently been introduced into Florida, where it occurs together with Thrips palmi. Methods to separate these two species are found in Kakkar et al. (2012). PCR techniques can also be used to identify thrips species (Walsh et al. 2005).

Host Plants

Melon thrips is a polyphagous species but is best known as a pest of Cucurbitaceae and Solanaceae. Tomato is reported to be a host in the Caribbean, but not in the United States or Japan. Tsai et al. (1995) reported that cucurbits were more suitable than eggplant, whereas pepper was less suitable than eggplant. In Japan, eggplant, cucumber, and melon are superior hosts (Kawai 1990).

Among vegetables injured are bean, cabbage, cantaloupe, chili, Chinese cabbage, cowpea, cucumber, bean, eggplant, lettuce, melon, okra, onion, pea, pepper, potato, pumpkin, squash, and watermelon.

Other crops infested include avocado, carnation, chrysanthemum, citrus, cotton, hibiscus, mango, peach, plum, soybean, tobacco, and others. Also, weeds can serve as important hosts, including species of nightshades (Solanaceae), legumes (Fabaceae or Leguminosae), and asters (Asteraceae or Compositae).

Damage

Melon thrips cause severe injury to infested plants. Leaves become yellow, white, or brown, and then crinkle and die. Heavily infested fields sometimes acquire a bronze color. Damaged terminal growth may be discolored, stunted, and deformed. Densities from 1 to 10 per cucumber leaf have been considered to be the threshold for economic damage in some Japanese studies. However, studies in Hawaii suggested a damage threshold of 94 thrips per leaf early in the growth of the plant (Welter et al. 1990). Feeding usually occurs on foliage, but on pepper, a less suitable host, flowers are preferred to foliage. Because melon thrips prefer foliage, they are reported to be less damaging to cucumber fruit than western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) (Rosenheim et al. 1990). Nevertheless, fruits may also be damaged; scars, deformities, and abortion are reported. Pepper and eggplant fruit are damaged when the thrips feed in blossoms. In Hawaii, thrips were observed to attain higher densities on cucumber plants infected with watermelon mosaic virus, but it was not determined whether the plants were more attractive to adults or suitable for survival and reproduction (Culliney 1990).

In addition to direct injury, melon thrips are capable of inflicting indirect injury by transmitting some strains of Tomato spotted wilt virus and bud necrosis virus.

Natural Enemies

Natural enemies, particularly predators, are important in the ecology of melon thrips. In fact, there is strong indication that melon thrips' abundance and damage are increased by application of some insecticides (Etienne et al. 1990). It is usually inadvisable to apply insecticides if predators are present. Some insecticides are not too disruptive to beneficial insect populations, but pyrethroids should be avoided. Among the most important predators observed in Hawaii were the predatory thrips Franklinothrips vespiformis (Crawford) (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae) and especially the minute pirate bug Orius insidiosus (Say) (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae).

Other predators in Hawaii were the lady beetle Curinus coeruleus (Mulsant) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), the predatory plant bug Rhinacoa forticornis Reuter (Hemiptera: Miridae), and the minute pirate bug Paratriphleps laevisculus Champion (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae). Other predators and parasitoids are known in Asia (Hirose 1991; Hirose et al. 1993; Kajita 1986). The parasitoid Ceranisus menes Walker (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) shows particular benefit in many Asian studies, and this wasp has been introduced to Florida (Castineiras et al. 1996a). Fungi known to affect melon thrips include Beauveria bassiana, Neozygites parvispora, Verticillium lecanii, and Hirsutella sp. (Castineiras et al. 1996b).

Management

Sampling

Larvae and adults generally are found on foliage. Adults tend to move toward young foliage, with nymphs tending to be clustered on foliage inhabited by adults several days earlier. Adults can also be sampled with sticky and water pan traps. Blue and white are attractive colors for thrips and have been used to trap melon thrips. However, yellow has also been suggested to be an attractive color (Culliney 1990).

Cultural Control

Several cultural practices apparently affect melon thrips abundance, but few have been evaluated in the context of North American agriculture. Physical barriers such as fine mesh and row cover material can be used to restrict entry by thrips into greenhouses and to reduce the rate of thrips settling on plants in the field.

Organic mulch is thought to interfere with the colonization of crops by winged thrips. Plastic mulch also is reported to limit population growth, but it is uncertain whether this is due to reduced rates of invasion or denial of suitable pupation sites. Crop stubble was not an effective deterrent (Litsinger and Ruhendi 1984).

Melon thrips can hitch-hike on food products, which can be a significant quarantine issue that affects the potential to ship produce to certain areas where the thrips is not known to occur. However, this (and many other) thrips are susceptible to atmospheric modification during shipping, which will kill the trips without damaging the commodity. High levels of carbon dioxide, particularly in conjunction with high temperatures, can be a useful fumigation technique (Seki and Murai 2012).

Heavy rainfall is thought to decrease thrips numbers (Etienne et al. 1990). However, there seems to be no evidence that overhead irrigation is an important factor in survival.

Host Plant Resistance

Nuessly and Nagata (1995) reported that susceptibility to injury varied among pepper cultivars. They reported that although sweet and jalapeno types were sensitive to foliar injury, cubanelle and cayenne types produced acceptable size and quality fruit. This is the reverse of injury susceptibility to western flower thrips, so in areas with mixed thrips populations growers cannot rely solely on plant selection to avoid damage.

Biological Control

The predatory mite Neoseiulus cucumeris (Oudemans) has been investigated for suppression of melon thrips (Castineiras et al. 1997). The mite density is correlated with thrips density, but within-plant distribution differs among the two species, suggesting that although the mites may increase in numerical abundance, they are unlikely to drive the thrips to extinction. In Colombia, several genotypes of beans displaying resistance to T. palmi have been identified (Cardona et al. 2002).

Chemical Control

Foliar insecticides are frequently applied for thrips suppression, but at times it has been difficult to attain effective suppression. Various foliar and drench treatments, alone or combined with oil, have achieved some success (Seal and Baranowski 1992, Seal et al. 1993, Seal 1994) though it is usually inadvisable to apply insecticides if predators are present, especially pyrethroids. The eggs, which occur in the foliar tissue, and the pupae, which reside in the soil, are relatively insensitive to insecticide application.

Selected References

Bhatti JS. 1980. "Species of the genus Thrips from India (Thysanoptera)." Systematic Entomology 5: 109–166.

CABI. December 1998. Thrips palmi Karny. Distribution Maps of Plant Pests. https://www.cabi.org/isc/abstract/20066600480 (22 February 2022).

Capinera JL. 2001. Handbook of Vegetable Pests. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Cardona C, Frei A, Bueno JM, Diaz J, Gu H, Dorn S. 2002. "Resistance to Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in beans." Journal of Economic Entomology 95:1066–1073.

Castineiras A, Baranowski RM, Glenn H. 1996a. "Temperature response of two strains of Ceranisus menes (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) reared on Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)." Florida Entomologist 79: 13–19.

Castineiras A, Baranowski RM, Glenn H. 1997. "Distribution of Neoseiulus cucumeris (Acarina: Phytoseiidae) and its prey, Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) within eggplants in south Florida." Florida Entomologist 80: 211–217.

Castineiras A, Pena JE, Duncan R, Osborne L. 1996b. "Potential of Beauveria bassiana and Paecilomyces fumosoroseus (Deuteromycotina: Hyphomycetes) as biological control agents of Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)." Florida Entomologist 79: 458–461.

Culliney TW. 1990. "Population performance of Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on cucumber infected with a mosaic virus." Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society 30: 85–89.

Etienne J, Guyot J, van Waetermeulen X. 1990. "Effect of insecticides, predation, and precipitation on populations of Thrips palmi on aubergine (eggplant) in Guadeloupe." Florida Entomologist 73: 339–342.

Frantz G, Parks F, Mellinger HC. 1995. Thrips population trends in peppers in southwest Florida. Pages 111-114 In Parker BL, Skinner M, Lewis T (eds.). Thrips Biology Management. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Frantz G, Mellinger HC. 1998. "Potential use of Beauveria bassiana for biological control of thrips in peppers." Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society 111: 79–81.

Girling DJ. (ed.) 1992. Thrips palmi. A Literature Survey with an Annotated Bibliography. International Institute of Biological Control, Silwood Park, Ascot, U.K. 37 pp.

Hirose Y. 1991. Pest status and biological control of Thrips palmi in southeast Asia. Pages 57-60 In Talekar NS (ed.). Thrips in Southeast Asia. Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

Hirose Y, Kajita H, Takagi M, Okajima S, Napompeth B, Buranapanichpan S. 1993. "Natural enemies of Thrips palmi and their effectiveness in the native habitat, Thailand." Biological Control 3: 1–5.

Johnson MW. 1986. "Population trends of a newly introduced species, Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), on commercial watermelon plantings in Hawaii." Journal of Economic Entomology 79: 718–720.

Kajita H. 1986. "Predation by Amblyseius spp. (Acarina: Phytoseiidae) and Orius sp. (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae) on Thrips palmi Karny (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)." Applied Entomology and Zoology 21: 484–484.

Kakkar G, Seal DR, Stansly PA, Liburd OE, Kumar V. 2012. "Abundance of Frankliniella schultzei (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in flowers on major vegetable crops of south Florida." Florida Entomologist 95: 468–475.

Kawai A. 1990. "Life cycle and population dynamics of Thrips palmi Karny." Japan Agricultural Research Quarterly 23: 282–288.

Litsinger JA, Ruhendi. 1984. "Rice stubble and straw mulch suppression of preflowering insect pests of cowpeas sown after puddled rice." Environmental Entomology 13: 500–514.

Nuessly GS, Nagata RT. 1995. Pepper varietal response to thrips feeding. Pages 115–118 In Parker BL, Skinner M, Lewis T (eds.), Thrips Biology and Management. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Oetting RD, Beshear RJ, Liu T-X, Braman SK, Baker JR. 1993. "Biology and identification of thrips on greenhouse ornamentals." Georgia Agricultural Experiment Station Research Bulletin 414. 20 pp.

Rosenheim JA, Welter SC, Johnson MW, Mau RFL, Gusukuma-Minuto LR. 1990. "Direct feeding damage on cucumber by mixed-species infestations of Thrips palmi and Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)." Journal of Economic Entomology 83: 1519–1525.

Seal DR. 1994. "Field studies in controlling melon thrips, Thrips palmi Karny (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on vegetable crops using insecticides." Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society 107: 159–162.

Seal DR, Baranowski RM, Bishop JD. 1993. "Effectiveness of insecticides in controlling Thrips palmi Karny (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on different vegetable crops in south Florida." Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society 106: 228–233.

Seki M, Murai T. 2012. "Responses of five adult thrips species (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) to high-carbon dioxide atmospheres at different temperatures." Applied Entomology and Zoology 47: 125–128.

Tsai JH, Yue B, Webb SE, Funderburk JE, Hsu HT. 1995. "Effects of host plant and temperature on growth and reproduction of Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)." Environmental Entomology 24: 1598–1603.

Walsh K, Boonham N, Barker I, Collins DW. 2005. "Development of a sequence-specific real-time PCR to the melon thrips Thrips palmi (Thysan., Thripidae)." Journal of Applied Entomology 129: 272–278.

Welter SC, Rosenheim JA, Johnson MW, Mau RFL, Gusukuma-Minuto LR. 1990. "Effects of Thrips palmi and western flower thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on the yield, growth, and carbon allocation pattern in cucumbers." Journal of Economic Entomology 83: 2092–2101.