Effects of Canals and Levees on Everglades Ecosystems (Fact Sheet)

Introduction

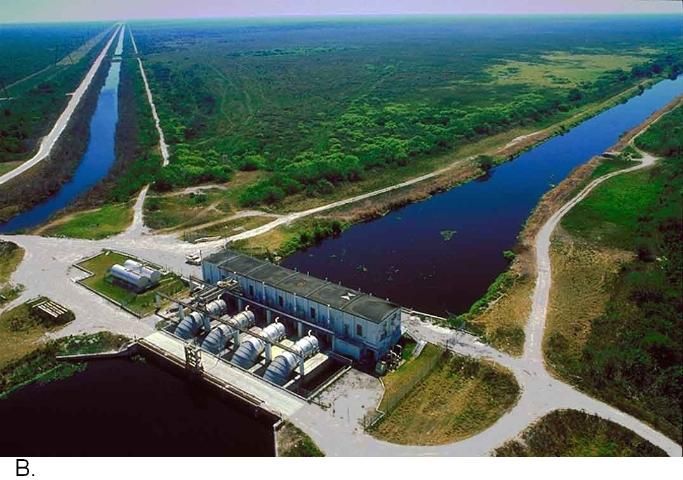

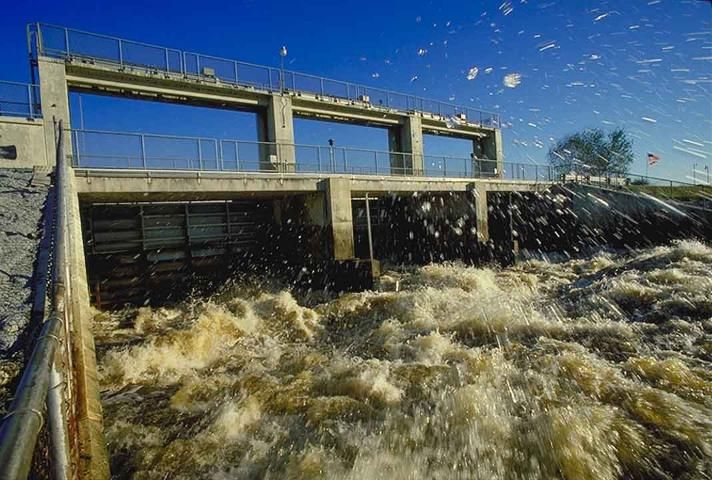

Canals and levees are the foundation of south Florida's water-management system. However, degradation of Everglades ecosystems has resulted directly from these structures and their effects of drainage and impoundment. The purpose of this fact sheet is to summarize the science on ecological and hydrological impacts of Everglades canals and levees.

Native peoples in south Florida built small, shallow canals to connect villages to coastal trade routes. By comparison, the modern canal system covers hundreds of linear miles with wider and deeper cuts. Canals and levees were created to drain and reclaim the wetlands for urban and agricultural use, to store and provide water to developed areas, and to provide flood control. They have met those objectives but, in the process, have transformed the landscape and ecology of south Florida.

Credit: Merald Clark. Source: MacMahon and Marquardt (2004)

Credit: SFWMD

How do canals and levees affect Everglades hydrology?

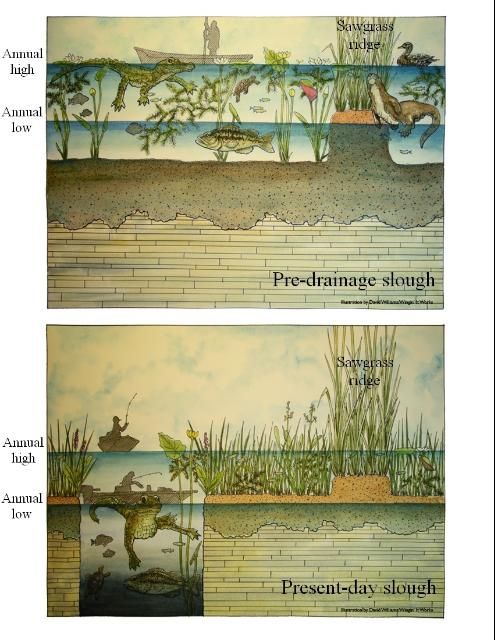

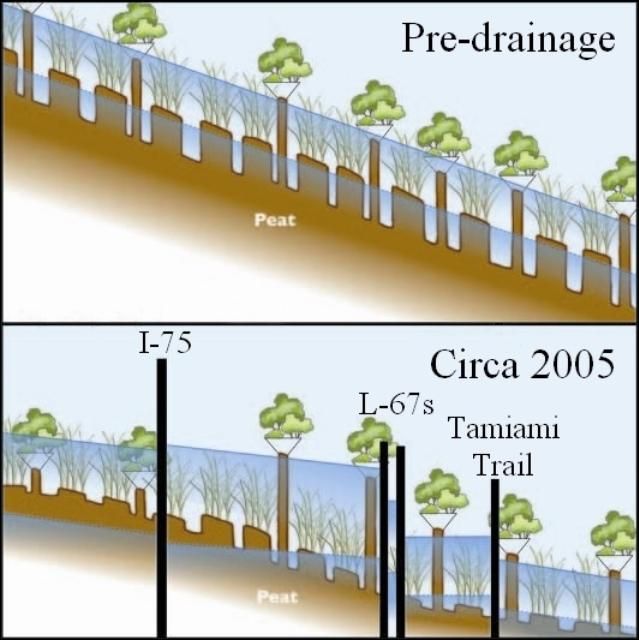

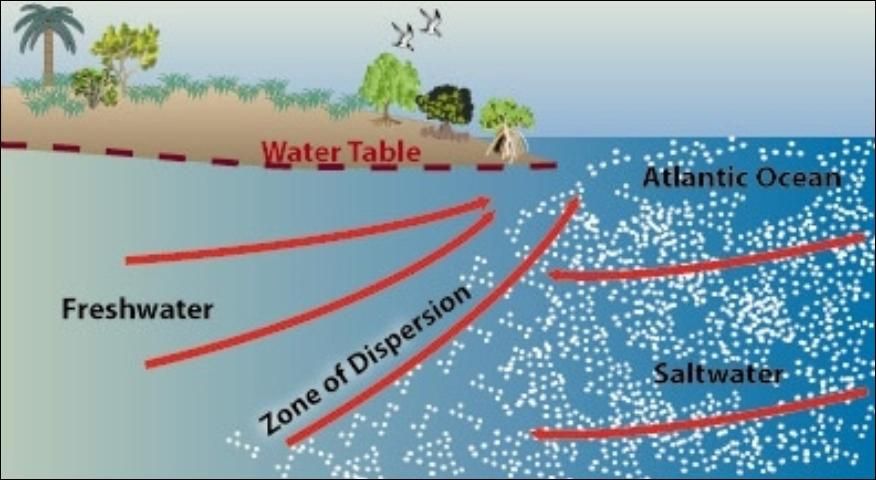

Canals draw water from the surrounding wetlands. In combination with reduced water deliveries, this results in completely dry land during the dry season, diminished aquatic habitat during the wet season, soil loss, and flattening of the peat surface. Canals also alter surface water chemistry by directly exposing surface water to the bedrock.

Levee construction replaced relatively even water depths and flows with a "stair-step" system of impoundments, simultaneously making upstream portions too dry and downstream ones too wet, leading to widespread vegetation and soil changes.

Credit: C. McVoy, SFWMD

How do canals and levees affect Everglades landscape and habitats?

Wetland Fragmentation

Hydrological barriers have led to loss of sheet flow and degradation of the distinct directional pattern of ridge and slough vegetation. The mosaic landscape has been replaced in many areas by large uniform stands of sawgrass, which offer fewer foraging areas and refuges for wildlife. Canals, levees, and roads also function as barriers to gene flow of aquatic fauna and to movement of fire across the landscape.

Credit: C. McVoy, SFWMD

Nonnative Species

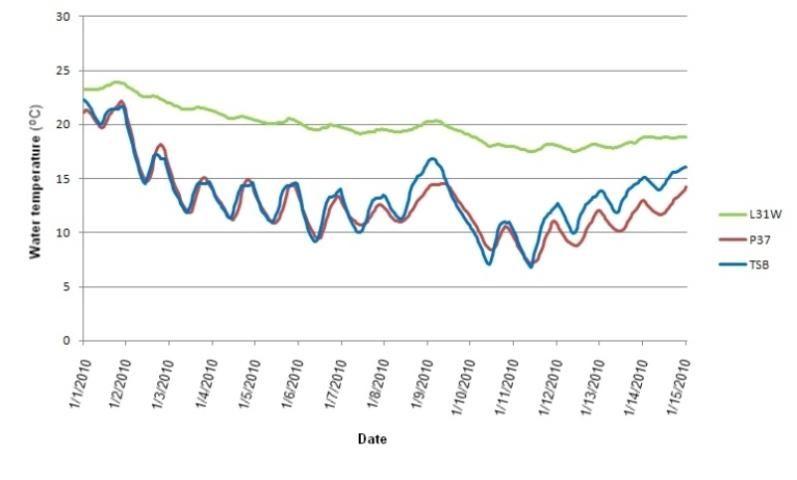

Canals facilitate establishment of nonnative fishes by offering permanent thermal and drought refuges. During the record cold event of January 2010, canal water temperatures remained above the lethal limits of nonnative fishes, which range from 6 to 15°C (43–59°F) (below). Canals also serve as pathways for nonnative species to invade interior wetlands, increasing the potential for impacts that may alter ecosystem structure and function.

Canals provide deep-water, nutrient-enriched habitats for expansion of nonnative pest plants such as water lettuce, hydrilla, and water hyacinth. These plants can modify water chemistry, deplete oxygen levels, shade out native species, decrease water flow, and interfere with navigation and flood control. Levees also provide disturbed upland habitat for noxious terrestrial pest plants, and corridors into the wetlands for insects such as fire ants.

Credit: J. Kline, NPS

Credit: D. Gandy, FIU

Refuges and Sinks

Canals provide habitat for dense populations of alligators, but these populations are dominated by adults. Nesting success in canals is negligible. Alligators that rely on canals may no longer construct and maintain alligator holes, which provide critical dry-season habitat for wetland fishes, amphibians, and wading birds.

The sport fishery in Everglades canals is "subsidized" by prey from the wetlands that are forced into canals in the dry season. Canals may act as sinks for forage species, which suffer heavy losses from native and nonnative predatory fishes. Without canals, prey fishes would remain on the marsh, available to wading birds. The effect of the loss of this forage base to wading birds requires study.

Credit: B. Jeffery and W. Guzman, UF

Credit: South Florida Fishing Adventures

How do canals and levees affect Everglades water quality?

Phosphorus delivery into wetlands via canals has led to replacement of periphyton/Utricularia mats with filamentous algal species that thrive in enriched waters, and the shift from a sawgrass-dominated vegetation community to one dominated by cattails. The most pronounced expansion of cattails is in WCA-2A, which receives water directly from the Everglades Agricultural Area. Cattails limit light penetration, decrease oxygen availability, and alter invertebrate and fish communities. Canals also transport chemical pesticides (e.g., endosulfan, atrazine) and sulfur (a mediator in methylation of mercury) into the Everglades.

Credit: H. Henkel, USGS

Credit: P. Fletcher, adapted from USGS