Introduction

Florida's native sword fern, also known as wild Boston fern (Nephrolepis exaltata) (Figure 1) and giant sword fern (Nephrolepis biserrata) (Figure 2) were highly admired by early botanists, naturalists, and horticulturists (Small 1918a, b; Simpson 1920; Foster 1984). Charles Torrey Simpson (1920) wrote: "the real glory of the hammock is the two species of Nephrolepis, one being the well-known 'Boston' fern." According to Foster (1984) "[N. exaltata] could be seen in homes and public buildings almost everywhere. They were the most desired plants of growers and yearly sales soared in the hundred thousands." In 1894, a cultivar of N. exaltata was discovered in a shipment from a Philadelphia grower to a Boston distributor and named N. exaltata cv. 'Bostoniensis', hence the name Boston fern (Foster 1984). Other derivatives of N. exaltata cv. 'Bostoniensis', ranging from 1-5-pinnae, and with such descriptive names as N. exaltata cv. 'Florida [Fluffy] Ruffles' were developed and are still known from Florida (FNA Editorial Staff 1993). The native sword fern and giant sword fern are still highly recommended for use as indoor and landscape plants (Broschat and Meerow 1991; Haehle and Brookwell 1999), but non-native, similar-appearing species of Nephrolepis now are also sold and confused with our native species.

Non-Native Species

Tuberous sword fern (Nephrolepis cordifolia) (Figure 3), not native to Florida, was found growing on a roadside in Sumter County, Florida in 1933 (Ward 2000) and in cultivation in Floral City, Florida in 1938 (Ward 2000). It is now found naturalized in pine rocklands, flatwoods, marsh edges, and hammocks of conservation areas of south Florida and as far north as Georgia (Langeland and Burks 1998). It was included on the Florida Exotic Pest Council's (FLEPPC) "1995 List of Florida's Most Invasive Species" in Category I, which means that it is invading and disrupting native plant communities in Florida. Tuberous sword fern is sold in the nursery and landscape trade, which may contribute to its further spread into native plant communities. The Florida Nurserymen and Growers Association (FNGA) and FLEPPC, in a 1999 joint decision, encouraged phase-out of tuberous sword fern from the growing and landscape market (Aylsworth 1999). Asian sword fern (Nephrolepis brownii) (Figure 4), also not native to Florida, was found growing and "driving out all other plants" on Sanibel Island, Lee County, Florida in 1954 (Ward 2000) and in Boca Chica, Monroe County, Florida in 1965 (Ward 2000). It was included on the Florida Exotic Pest Council's (FLEPPC) "1993 List of Florida's Most Invasive Species" in Category II and moved to Category I in 1999.

Tuberous sword fern and Asian sword fern are similar in appearance to the native sword fern and giant sword fern. Tuberous sword fern is sold under various names (e.g., Boston fern, hardy fern, large fern, erect sword fern) and names are often interchanged among the different species. Tuberous sword fern is most often confused with and sold in some stores as the native sword fern. The purpose of this fact sheet is to help consumers, distributors, growers, and land managers to distinguish between these species. Fishtail sword fern (Nephrolepis falcata), is non-native to Florida and escaped from cultivation (Wunderlin and Hansen 2000) but is not considered invasive. It is easily distinguished from the other species by its 1- to 3-dichotomously forked pinnae and will not be discussed further. Petticoat fern (Nephrolepis hirsutula), also sold in the nursery trade, is not known to have escaped cultivation and likewise will not be discussed. Averys sword fern (Nephrolepis x averyi) is a natural hybrid of N. biserrata x N. exaltata.

Identification

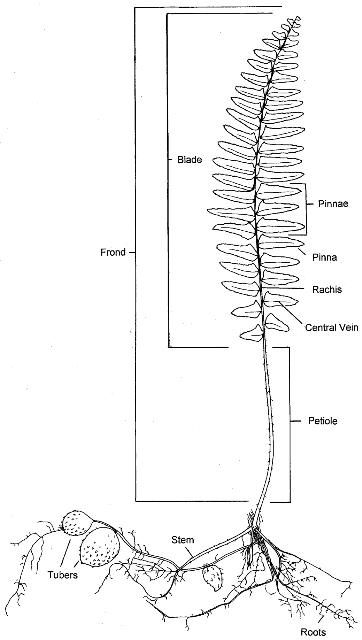

Use the narrative below, the dichotomous key (Table 1, adapted from Nauman 1981), or Table 2, which contrasts characteristics of the four species of Nephrolepis, along with the pictures of key characters, to distinguish them. Use Figure 5 and the glossary provided to help understand terminology used in the key and table. The interested reader will also find the following publications useful:

Coile, N. C. 1996. "Which Boston Fern Is It? The Exotic Nephrolepis cordifolia (L) Presl, or the Native Nephrolepis exaltata (L.) Schott." Botany Circular No. 32. Gainesville, FL: Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Hovenkamp, P. H., and Miyamoto, F. 2002. A conspectus of the native and naturalized species of Nephrolepis (nephrolepidaceae) in the world. Blumea 50: 279-322.

Nelson, G. 2000. The Ferns of Florida. Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press.

Wunderlin, R. P., and B. F. Hansen. 2000. Flora of Florida, Volume 1, Pteridophytes and Gymnosperms. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Tuberous sword fern, as the name implies, sometimes produces tubers (Figure 6), and it is the only one of the four species that is capable of producing them. Therefore, if tubers are present on the plants, this alone is a positive identification for this species. The presence of scales on the upper side of the rachis that have a point of attachment that is distinctively darker than the rest of the scale (Figure 7) will also distinguish tuberous sword fern from the other three species. Native sword fern, in contrast, has scales on the upper side of the rachis that are of one color (Figure 8). Another good characteristic to distinguish tuberous sword fern is that the pinnae (medial) are close together, the lobes overlapping the next closest pinnae, and the pinnae (medial) bases overlap and hide the rachis underneath (Figure 9). Tuberous sword fern is the smallest of the four species, having shorter fronds and pinnae (Figure 10). The fronds of tuberous sword fern are more erect than those of sword fern, the latter usually having long and weeping fronds. The pinnae of tuberous sword fern are usually straight and blunt contrasted to those of the native sword fern, which are mostly sword shaped and gradually narrowing to a point at the apex (Figure 10). A final contrast of tuberous sword fern and the native sword fern can be made of the indusia if they are present, those of tuberous sword fern being more kidney- to crescent-shaped or triangular-rounded than those of the native sword fern, which are more rounded to horseshoe-shaped (Figure 11).

Tuberous sword fern can be distinguished from Asian sword fern and giant sword fern by its glabrous central vein of the pinnae contrasted to the presence of short stiff hairs that occur on the central vein of the pinnae of Asian and giant sword fern (Figure 12). These can be observed best by bending the pinnae and looking at the curve created while holding it up to light. The most distinguishing characteristic for Asian sword fern is a dense covering of dark brown, appressed scales with pale margins on mature petioles (Figure 13). In contrast: 1) The petiole scales of tuberous sword fern are dense, spreading, and pale brown; 2) those of the native sword fern are sparse to moderate, reddish-brown, of a single color or slightly darkened at the point of attachment, and have expanded bases with small marginal hairs; and 3) those of giant sword fern are sparse to moderate, reddish to light brown and hair-like. Other features that will help distinguish the species are: 1) The hairy appearance of the rachis of Asian sword fern, owing to abundant two-colored, hairy scales, and 2) the fronds and pinnae of giant sword fern, which are much longer than those of the other species.

Control

Hand pulling can be used to remove some of the fern plants, but the plants will break off, leaving plant parts in the ground from which regrowth will occur. Because some plants are difficult to up-root and the rachis can cut the skin, wear heavy gloves. Do not dispose of these or other invasive plant species where they will cause new infestations.

Plants can be killed with herbicide products that contain the active ingredient glyphosate. A foliar application of a product that contains 41.0% glyphosate diluted to 1.5% v/v of product provides control. Follow-up applications are necessary. Several products are available from garden and agricultural supply stores. Different products may vary in concentration, so follow instructions for diluting the product provided on the herbicide label, as well as all other label instructions. Products that contain glyphosate will kill desirable plants that they contact, so apply carefully.

Glossary

Appressed: Lying flat or close against.

Attenuate: Gradually narrowed to a long point at the apex.

Acute: Sharply angled, the sides of the angle essentially straight.

Frond: A large divided leaf.

Glabrous: Without hairs.

Indusia: An outgrowth of tissue that covers the spore-producing structures in ferns.

Medial pinnae: Referring to those pinnae of the central portion of the frond.

Pubescent: Hairy.

Pinnae: Primary division of a compound leaf or frond of a fern.

Rachis: The central prolongation of the frond stalk.

Scale: An outgrowth of the epidermis having cell dimensions in two planes.

Tomentose: Densely covered with short matted hairs.

Trichomes: A hairlike outgrowth of the epidermis.

Tuber: A thickened, solid portion of an underground stem.

Literature Cited

Aylsworth, J. D. 1999. "Invasive Is Out." Ornamental Outlook 8: 40,42.

Broschat, T. K., and A. W. Meerow. 1991. Betrocks Reference Guide to Florida Landscape Plants. Cooper City, FL: Betrock Information Systems, Inc.

FNA Editorial Staff. 1993. Flora of North America North of Mexico, Volume 2, Pteridophytes and Gymnosperms. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Foster, F. G. 1984. Ferns to Know and Grow. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

Haehle, R. G., and J. Brookwell. 1999. Native Florida Plants. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Co.

Langeland, K.A., and K. Craddock Burks. 1998. Identification and Biology of Non-Native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas. SP257. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Nauman, C. E. 1981. "The genus Nephrolepis in Florida." American Fern J. 2: 35-40.

Small, J. K. 1918a. Ferns of Royal Palm Hammock. New York, NY: Published by the author.

Small, J. K. 1918b. Ferns of Tropical Florida. New York, NY: Published by the author.

Simpson, C. T. 1920. In Lower Florida Wilds. New York, NY: G. P. Putnams Sons Knickerbocker Press.

Wunderlin, R. P., and B. F. Hansen. 2000. Flora of Florida, Volume 1, Pteridophytes and Gymnosperms. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.