Symptoms

Boron (B) deficiency results in a wide array of symptoms, not only among species of palms, but also within a single species. Symptoms always occur on newly emerging leaves, but remain visible on these leaves as they mature and are replaced by younger leaves.

One of the earliest symptoms of B deficiency on Dypsis lutescens (areca palm) and Syagrus romanzoffiana (queen palm) is transverse translucent streaking on the leaflets. In many species, including Cocos nucifera (coconut palm), Elaeis guineensis (African oil palm), and S. romanzoffiana, mild B deficiency can be manifested as sharply bent leaflet tips, commonly called "hookleaf" (Figure 1). These sharp leaflet hooks are quire rigid and cannot be straightened without tearing the leaflets.

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Boron deficiency can be very transient in nature, often affecting a developing leaf primordium for a very short period of time (e.g., 1 to 2 days). This temporary shortage of B can cause necrosis (dead tissue) on the primordial spear leaf for a distance of about 1 to 2 cm. When such leaves eventually expand, this "point" necrosis affects the tips of all leaflets intersected by that necrotic point, the net result being the appearance of a blunt, triangular truncation of the leaf tip (Figures 2 and 3). This pattern can be repeated as many as three times during the development of a single leaf of Cocos nucifera (about 5 weeks) (Figure 4).

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

One of the most common symptoms of B deficiency is the failure of newly emerging spear leaves to open normally. They may be tightly fused throughout their entire length, or the fusion can be restricted to basal or distal parts of the spear leaf. In a chronic state, multiple unopened spear leaves may be visible at the apex of the canopy (Figures 5 and 6).

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

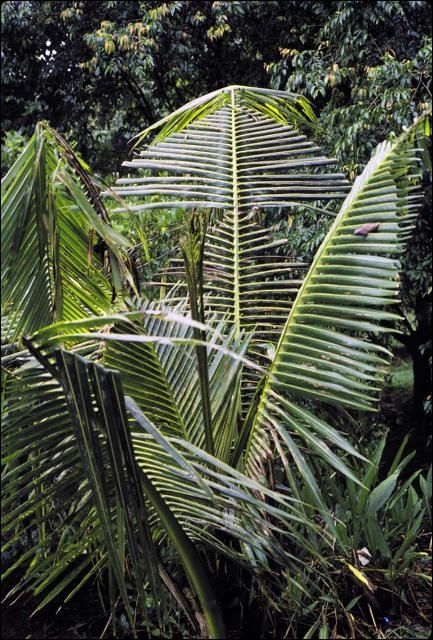

Perhaps the most unusual symptoms of chronic B deficiency is the tendency for the entire crown to bend in one direction (Figures 7 and 8). This is one form of epinasty that can also cause twisting of petioles and leaves or sharp bends in the petiole, resulting in a single new leaf growing downward along the trunk (Figure 9). These epinastic symptoms are believed to be caused by a B deficiency-induced decrease in IAA-oxidase activity and therefore excessive auxin concentrations within the leaves.

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

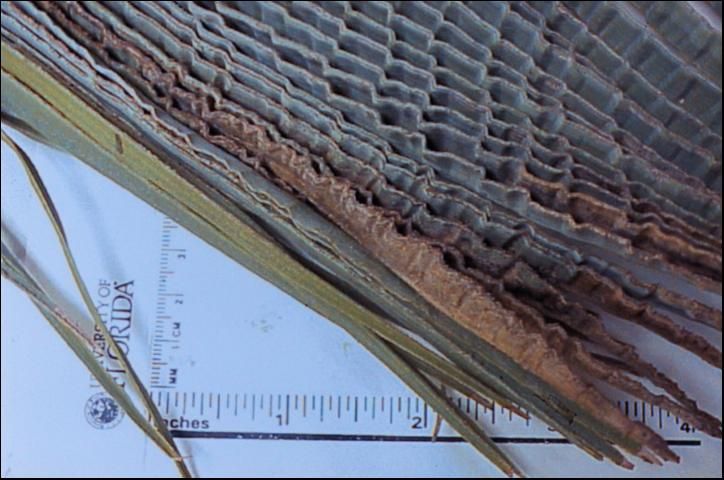

Boron deficiency in its acute form produces yet other symptoms. Often leaves emerge greatly reduced in size and crumpled in a corrugated fashion (accordion leaf) (Figures 10 and 11). Palms often grow out of these symptoms, but the deficiency may kill the meristem.

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Boron-deficient palms often abort their fruits prematurely and inflorescences may have extensive necrosis near their tips (Figures 12 and 13). These symptoms are very similar to those of lethal yellowing (LY) in species affected by that disease. The calyx end of fallen coconuts from LY-infected Cocos nucifera will be blackened, whereas coconuts from B-deficient trees will not have this blackened end.

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Cause

Boron deficiency is caused by insufficient B in the soil. Boron is readily leached through most soils, with a single heavy rain event temporarily leaching most available B out of the root zone. When this leaching stops, B released from decomposing organic matter will again provide adequate B for normal palm growth in most cases. Boron deficiency is also common in deserts and seasonally dry areas where soil drying tightly binds B. Chronic B deficiency is believed to be caused by soil drying and high soil pH, while temporary B deficiency is caused by heavy leaching.

Occurrence

Boron deficiency is very widespread on palms growing in wet climates throughout the world, but can also occur in desert climates. Boron deficiency has been observed in container-grown palms, especially in seedlings.

Diagnostic Techniques

Boron deficiency symptoms are quite distinctive and are usually sufficient for diagnosis by themselves. Manganese deficiency in Cocos nucifera produces symptoms similar to those of B deficiency, but Mn-deficient leaves show necrotic truncations of all leaflets, not just those near the tip of the leaf. No other common deficiency produces symptoms that could be confused with those of B deficiency.

Because B deficiency is often very transient in nature, the element is immobile within the palm (cannot move from one leaf to another), and deficiencies affect only leaf primordia developing within the bud area, leaf analysis is not particularly useful. Leaf analysis tells you the B status of the single leaf that you sampled, but that is not the current B status of the newly developing leaves within the bud area. Rather, it indicates the B status of the palm 4 or 5 months ago when the sampled leaf itself was in the developmental stage within the bud. The B status of the palm is likely to have changed considerably one way or another during 4 or 5 months since the affected leaf became old enough to sample. Thus, leaf analysis, or even leaf symptoms, unless the deficiency is chronic (regularly occurring), cannot tell you about the current B status of a palm. Similarly, soil analysis is not recommended for diagnosis of B deficiency.

Management

Because the difference between deficiency and toxic levels of B within plants is rather small, extreme caution should be exercised when applying B fertilizers. Recommended landscape maintenance fertilizers typically contain 0.05%–0.15% B, and that appears to be sufficient to prevent B deficiencies in most cases. One product, Granubor®, has a longevity of about 3 months, making it suitable for blending with other slow-release fertilizers that have similar longevities. Its granular form also prevents it from settling out in mixed fertilizers. Water-soluble sodium borates such as Solubor® or Borax suffer from several problems when incorporated into granular fertilizer blends. First, they are typically powders, which tend to settle to the bottom of a fertilizer bag. Fertilizer taken from the top of the bag may contain insufficient B for plant needs, while fertilizer taken from the bottom may contain toxic concentrations of B. Also, water-soluble B fertilizers are readily lost to leaching during excessive rainfall, rendering them less effective than slow-release forms.

Current recommendations for correcting B deficiencies in palms are intentionally conservative because of the potential for toxicity. Dissolve about 2–4 oz of Solubor® or Borax in 5 gallons of water and drench this into the soil under the canopy of a single palm. Do not attempt to apply dry B fertilizers to the soil, because turfgrass or other groundcovers in contact with it may be killed. Do not repeat this for at least 5 months, because it will take this long to see the results of the first application.

Selected References

Broschat, T.K. 1984. Nutrient deficiency symptoms in five species of palms grown as foliage plants. Principes 28:6–14.

Broschat, T.K. Boron deficiency symptoms of palms. Palms 51:115–126.

Broschat, T.K. Boron deficiency, phenoxy herbicides, stem bending, and branching in palms—is there a connection? Palms 51:161–163.

Broschat, T.K. 2008. Release rates of soluble and controlled release boron fertilizers. HortTechnology 18:471–474. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH.18.3.471

Brunin, C. and P. Coomans. 1973. La carence en bore sur jeunes cocotiers en Côte DIvoire. Oléagineux 28:229–234.

Bull, R.A. 1961. Studies on the deficiency symptoms of the oil palm. 3. Micronutrient deficiency symptoms in oil palm seedlings grown in sand culture. J. West African Inst. Oil Palm Res. 3:265–272.

Manciot, E., M. Ollagnier, and R. Ochs. 1979-80. Mineral nutrition of the coconut around the world. Oléagineux 34:511–515; 576–580; 35:23–27.

Marlatt, R. B. 1978. Boron deficiency and toxicity symptoms in Ficus elastica and Chrysalidocarpus lutescens. HortScience 13:442–443. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.13.4.442

Ollagnier, M. and G. Valverde. 1968. Contribution à letude de la carence en bore du palmier à huile. Oléagineux 23:359–366.

Rajaratnam, J.A. 1972a. Observations on boron-deficient oil palms (Elaeis guineensis). Exp. Agr. 8:339–346. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479700005469