The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The brown citrus aphid, Toxoptera citricida (Kirkaldy), is one of the world's most serious pests of citrus. Although brown citrus aphid alone can cause serious damage to citrus, it is even more of a threat to citrus because of its efficient transmission of citrus tristeza closterovirus (CTV). One of the most devastating citrus crop losses ever reported followed the introduction of brown citrus aphid into Brazil and Argentina: 16 million citrus trees on sour orange rootstock were killed by CTV (Carver 1978).

Distribution

The current distribution of brown citrus aphid includes Southeast Asia (Carver 1978; Tao and Tan 1961), Africa south of the Sahara, Australia, New Zealand, the Pacific Islands, South America, the Caribbean, and Florida. So far, the remainder of U.S. citrus-producing areas and the Mediterranean, except (since 1994) for the island of Madeira (Aguilar et al. 1994), have remained free of the pest (Blackman and Eastop 1994).

The initial counties found to be infested in Florida were Dade and Broward, and the majority of infested trees were in dooryard situations. Several months after detection, infestations were discovered in the commercial lime production area, indicating range expansion about 15 miles south of the area delimited by the original survey. An eventual spread throughout Florida is expected.

Identification

Worldwide, 16 species of aphids are reported to feed regularly on citrus. Four more species may be occasional pests (Blackman and Eastop 1984; Stoetzel 1994). Of these 20 species, four are found consistently in Florida groves:

-

Aphis craccivora Koch, cowpea aphid

-

Aphis gossypii Clover, cotton or melon aphid

-

Aphis spiraecola Patch, spirea aphid

-

Toxoptera aurantii (Boyer de Fonscolombe), black citrus aphid

An additional three species are rarely collected on citrus in Florida and are not considered pests of the crop. These are:

-

Aphis nerii Boyer de Fonscolombe, oleander aphid

-

Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Thomas), potato aphid

-

Myzus persicae (Sulzer), green peach aphid

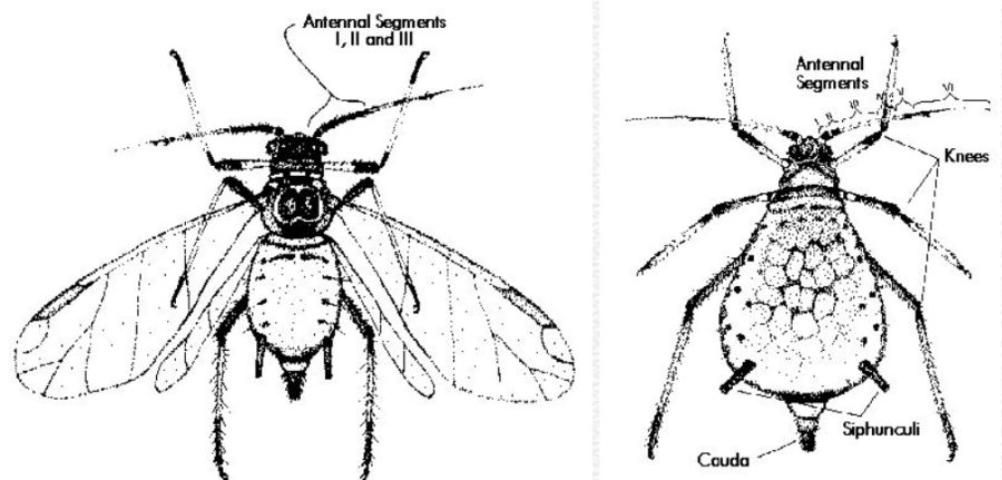

Brown citrus aphid is larger than other species occurring on citrus. Adult wingless forms (apterae) are very shiny black, and nymphs are dark reddish-brown. However, field identification of brown citrus aphid can be difficult because four of the five regularly collected species can be dark in color, and all five species colonize new growth. Additionally, mixed colonies of two or more species are common. Adult winged forms (alatae) of brown citrus aphid are distinctive. They can be recognized by the conspicuous black antennal segments I, II and III. Identification is easier with alatae than with adult apterae or nymphs, but alatae are less common in the field because they tend to leave the colony soon after they emerge. The following key to adult apterae will separate most colonies in the field with the aid of a hand lens. Characters that require microscopic examination are included in parentheses. It will not always be possible to separate brown citrus aphid from A. craccivora in the field, but the latter species is not very common. Identification of alatae of most species of aphids on Florida citrus has been covered earlier (Denmark 1990). Another excellent source of identification using microscopic characters is Stroyan (1961). Please refer to the wingless form graphic for an illustration of aphid terminology for field identification.

Credit: Amie Smith, DPI

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Aphid Biology

The life cycle of brown citrus aphid is much less complex than that of most aphids. In most areas of the world, brown citrus aphid is permanently anholocyclic, meaning that there is no sexual cycle in the autumn, and thus, no males, no oviparae, and no eggs. All individuals throughout the year are viviparous parthenogenetic females. In Japan, there is a functional holocycle on citrus (Komazaki 1988). It is expected that brown citrus aphid will be permanently anholocyclic in the major citrus production areas of Florida. Populations of brown citrus aphid increase very rapidly under favorable conditions. Nymphs mature in six to eight days at temperatures of 20ºC or higher (Komazaki 1988). Komazaki (1988) calculated the capacity for increase for brown citrus aphid to be 0.4 at about 25ºC a single aphid could produce a population of over 4,400 in three weeks in the absence of natural enemies.

Field Key to Adult Wingless Forms (apterae) of Common Aphids on Citrus in Florida

1. Aphids yellow or green; adult wingless forms with cauda as dark as siphunculi; (6–13 setae on the cauda; ultimate rostral segment [the terminal segment of the mouthparts] 0.07–0.13 mm long) ..... Aphis spiraecola (spirea aphid)

1'. Aphids black, grey or tan; other characters variable ..... 2

2. Cauda of adult wingless forms significantly paler than siphunculi; aphids variable in color but not shiny black; antennae not with stripes; "knees" pale; (cauda with two or three pairs of setae; setae on antennal segment III not longer than the diameter of the segment) ..... Aphis gossypii (cotton or melon aphid)

2'. Cauda of adult wingless forms black, just as dark as the siphunculi; aphids dark, sometimes very shiny black; at least "knees" of hind legs black; (setae variable) ..... 3

3. Antennae of adult wingless forms and larger nymphs with joints of most segments darkened so that they appear striped; adult apterae matte black in color, nymphs reddish brown or grey (stridulatory organ present; cauda with 10–20 setae; setae on antennal segment III shorter than the diameter of the segment) ..... Toxoptera aurantii (black citrus aphid)

3'. Antennae of adult wingless forms and larger nymphs not striped, but dark on the distal 1/3–1/2 its length; adult apterae shiny black, nymphs red-brown or grey; other characters variable ..... 4

4. "Knees" of all three pairs of legs very dark; dark portion of the antenna about 1/2 of its length; siphunculi only slightly longer than the cauda; (stridulatory organ present; cauda with about 30 setae; setae on antennal segment III at least as long as the diameter of the segment; antennal segment III slightly swollen) ..... Toxoptera citricida (brown citrus aphid)

4'. "Knees" usually dark only on hind legs; dark portion of the antenna only about 1/3 of its length; siphunculi much longer than the cauda; (stridulatory organ absent; cauda with about 7 setae; setae on antennal segment III not nearly as long as the diameter of the segment; antennal segment III never swollen) ..... Aphis craccivora (cowpea aphid)

Host Plants

Most aphidologists believe that the preferred host range of brown citrus aphid is limited to citrus and a few close relatives (Aguiar 1994; Blackman and Eastop 1984, 1994; Carver 1978; Stoetzel 1994; Stroyan 1961; Yokomi 1994). However, brown citrus aphid has been reported to form large colonies on the new growth of other plants in several families. It is not known which, if any, of these reports are the result of misidentifications or collections of incidental specimens. It is possible that under some environmental conditions, brown citrus aphid can colonize the new growth of plants that are normally not hosts. Alternatively, it is not known how genetically variable world populations of brown citrus aphid are; thus, it is possible that variants exist that regularly colonize host plants outside the Rutaceae. In particular, van Harten and Ilharco (1975) note a tendency for brown citrus aphid to feed on Rosaceae in southern Africa and Mauritius. The host range of brown citrus aphid in Florida is not clearly known.

Epidemiology of Citrus Tristeza Closterovirus

Citrus tristeza closterovirus is a phloem-limited virus. This aspect of its biology limits its vectors, for all practical purposes, to those aphid species that colonize the crop (though not all crop colonizers are vectors). Brown citrus aphid is much more efficient at transmitting CTV than other aphids that infest citrus. It is six to 25 times as efficient as A. gossypii, the most efficient vector of CTV in Florida prior to 1995 (Yokomi et al. 1994). Besides its intrinsic efficiency, two other factors contribute to the important vector status of brown citrus aphid. These include its relatively narrow host range and its tendency to produce winged forms as colonized new growth matures. A. gossypii has a very wide host range, including hundreds of plant species in Florida. Thus, a viruliferous winged A. gossypii that leaves a citrus tree is less likely to feed immediately on another citrus tree (and transmit the virus) than on some other plant, where the virus meets a dead end. Brown citrus aphid, on the other hand, because of its narrow host range, is most likely to feed on another citrus tree, potentially infecting it with CTV. Brown citrus aphid also transmits some strains of CTV that are not transmissible by other species (Yokomi et al. 1994, Yokomi 1995). This increases the likelihood that there will be a gradual increase in severity of citrus tristeza in Florida (Schoulties et al. 1987).

Credit: Division of Plant Industry, www.insectimages.org

Management

Cultural control

It is clear that CTV-induced quick decline of citrus trees propagated on sour orange and other susceptible rootstocks has become a fact of life in areas where brown citrus aphid has become established. In Florida, strains of CTV that cause quick decline are widespread in citrus on CTV-tolerant rootstocks. Field evaluation of alternate rootstocks will enable a smoother transition away from sour orange (Rocha-Pefla et al. 1995). Citrus is propagated vegetatively, which greatly increases the possibility for spreading disease because CTV is graft transmissible. Man can quickly spread citrus tristeza virus faster and farther than any aphid. One pickup truck of infested nursery stock can spread the virus several hundred miles in a few hours from nursery sites to grove plantings.

The first step in any integrated management program should be to ensure that budwood and nursery stock are free of disease (with the possible exception of mild strains of CTV used for cross protection). The department's budwood protection program will periodically test all sources of propagating material for several graft-transmissible pathogens of citrus including CTV, porosis, cachexia, exocortis and tatterleaf. Mandatory budwood certification will require source trees to have annual tests for CTV, where sources testing positive for severe strains of CTV will no longer be permitted to be used for propagation. Having a known clean pool of propagating material and protecting that pool will help ensure that we are not introducing or intentionally moving pathogens within Florida.

Another aspect of cultural control is inoculum suppression. Although aphids can fly 30 km or more, most flight is probably local (Loxdale et al. 1993). Thus, nearby sources of inoculum are much more important than distant ones (Bishop 1965, 1967; Bishop and Guthrie 1964). Abandoned and/or volunteer crop plants can become reservoirs of pests and disease (Bishop et al. 1992; Plumb and Johnstone 1995). Likewise, urban areas may be reservoirs of crop viruses and vectors (Bishop and Guthrie 1964). As much as it is feasible, it is essential to protect propagative source trees from nearby sources of aphid infestation and virus infection.

Biological control

Aphids in general have several kinds of natural enemies including parasites, predators and pathogens. Brown citrus aphid is no exception, but the degree to which natural enemies can suppress brown citrus aphid populations is not well known. It is also not known whether suppression of brown citrus aphid populations will reduce spread of CTV. In any case, brown citrus aphid is also a direct pest, and establishment of effective parasites and predators that will reduce brown citrus aphid populations would be beneficial. Under humid Florida conditions, fungi applied as bio-insecticides may be useful for brown citrus aphid population suppression. Aphids are also susceptible to viral pathogens, but caution with this approach for control of brown citrus aphid is suggested because at least one viral pathogen of aphids (Rhopalosiphum padi virus) may enhance transmission of a plant virus (barley yellow dwarf virus) (Damsteegt et al. 1992).

Host plant resistance

It is very difficult to breed horticulturally useful citrus trees. Some of our favorite fruit plants (grapefruit, for example) may be derived from hybrids. Thus, standard crossing may not produce acceptable fruit. Besides that, it may take 10 years or more before production characteristics can be reliably evaluated. Because of these difficulties, there has been active research on the possibilities for genetic engineering.

Cross protection

Cross protection is the practice of deliberately infecting trees with a mild strain of CTV in order to prevent or delay infection or symptom expression by severe strains of the pathogen. The technique is used with success in Australia (Broadbent et al. 1995) and South Africa (van Vurren 1995) and is in limited use in Florida (Lee et al. 1995). Deliberately infecting a crop with a pathogen should be done with great caution. Experience in Australia and South Africa indicates that cross protection will prolong the economic life of a grove, but that performance of cross protected plantings is not equivalent to that of virus resistant plantings. Thus, permanent genetic resistance to CTV is still an important goal.

Chemical control

It is not known whether controlling aphids will reduce spread of CTV in production situations, but insecticides may be beneficial in protecting nursery stock and valuable budwood sources. Consult the Florida Citrus Pest Management Guide for specific recommendations.

Selected References

Aguiar AMF, Fernandes A, Ilharco FA. 1994. On the sudden appearance and spread of the black citrus aphid Toxoptera citricidus (Kirkaldy), (Homoptera: Aphidoidea) on the island of Madeira. Bocagiana Museu Municipal do Funchal (Historia Natural) 168: 1–7.

Bishop GW. 1965. Green peach aphid distribution and potato leaf roll virus occurrence in the seed potato producing areas of Idaho. Journal of Economic Entomology 58: 150–153.

Bishop GW. 1967. A leaf roll virus control program in Idaho'sseed potato areas. American Potato Journal 44: 305–308.

Bishop GW, Guthrie JW. 1964. Home gardens as a source of green peach aphid and virus disease in Idaho. American Potato Journal 41: 28–34.

Bishop GW, Kleinschmidt GD, Knutson KW, Mosley AR, Thornton RE, Voss RE. 1992. Integrated Pest Management for Potatoes in the Western United States. University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Oakland, CA. Publication 3316. 146 pp.

Blackman RL, Eastop VF. 1984. Aphids on the World's Crops. John Wiley & Sons, N.Y. 466 pp.

Blackman RL, Eastop VF. 1994. Aphids on the World's Trees. Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau International, Wallingford, UK. 987 pp.

Broadbent P, Depoff CM, Franks N, Gillings M, Indsto I. 1995. Pre-immunisation of grapefruit with a mild protective isolate of citrus tristeza virus in Australia. pp. 163, 165–168. In Lee R, Roca-PeAa M, Niblett CL, Ocoa F, Garnsey SM, Yokomi RK, Lastra R (editors). Citrus tristeza virus and the brown citrus aphid in the Caribbean Basin Management strategies. Proceedings of the Third International Workshop, University of Florida, Lake Alfred, FL.

Carver M. 1978. The black citrus aphids, Toxoptera citricidus (Kirkaldy) and T. aurantii (Boyer de Fonscolombe) (Homoptera: Aphididae). Journal of the Australian Entomological Society 17: 263–270.

Damsteegt VD, Gildow FE, Hewings AD, Carroll TW. 1992. A clone of the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia) as a vector of the barley yellow dwarf, barley stripe mosaic and brown mosaic viruses. Plant Disease 76: 1155–1166.

Denmark HA. 1990. A field key to the citrus aphids in Florida (Homoptera: Aphididae). Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, Gainesville, Florida. Entomology Circular No. 335. 2 pp.

Komazaki S. 1987. Growth and reproduction in the first two and summer generations of two citrus aphids, Aphis citricola van der Goot and Toxoptera citricidus (Kirkaldy) (Homoptera: Aphididae), under different thermal conditions. Applied Entomology and Zoology 23: 220–227.

Lee RF, Derrick KS, Niblett CL, Pappu HR. 1995. When to use mild strain cross protection (MSCP) and problems encountered. pp. 158–161, 164. In Lee R, Roca-PeAa M, Niblett CL, Ocoa F, Garnsey SM, Yokomi RK, Lastra R (editors). Citrus tristeza virus and the brown citrus aphid in the Caribbean Basin Management strategies. Proceedings of the Third International Workshop, University of Florida, Lake Alfred, FL.

Loxdale HD, Hardie J, Halbert S, Foottit R, Kidd NAC, Carter CI. 1993. The relative importance of short- and long-range movement of flying aphids. Biological Reviews 68: 291–311.

Plumb RT, Johnstone GR. 1995. Cultural, chemical, and biological methods for the control of barley yellow dwarf. pp. 307–319. In D'Arcy CJ, Barnett PA (editors). Barley Yellow Dwarf - 40 Years of Progress. APS Press, St. Paul, MN.

Roca-PeAa MA, Lee RF, Lastra R, Niblett CL, Ochoa-Corona FM, Garnsey SM, Yokomi RK. 1995. Citrus tristeza virus and its aphid vector, Toxoptera citricida. Threats to citrus production in the Caribbean and Central and North America. Plant Disease 79: 437–445.

Schoulties CL, Brown LG, Youtsey CO, Denmark HA. 1990. Citrus tristeza virus and vectors: Regulatory concerns. Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society 100: 74–76.

Stoetzel MB. 1994. Aphids (Homoptera: Aphididae) of potential importance on Citrus in the United States with illustrated keys to species. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 96: 74–90.

Stroyan HLG. 1961. Identification of aphids living on citrus. FAO Plant Protection Bulletin 9: 45–68.

Tao CC, Tan MF. 1961. Identification, seasonal population and chemical control of citrus aphids of Taiwan. Journal of Agricultural Research 10: 41–53.

van Harten A, Ilharco FA. 1975. A further contribution to the aphid fauna of Angola, including the description of a new genus and species. (Homoptera: Aphidoidea). Agronomia Lusitana 37: 13–35.

van Vurren SP. 1995. Mild strain cross protection in South Africa. pp. 169–173. In Lee R, Roca-PeAa M, Niblett CL, Ocoa F, Garnsey SM, Yokomi RK, Lastra R (editors). Citrus tristeza virus and the brown citrus aphid in the Caribbean Basin Management strategies. Proceedings of the Third International Workshop, University of Florida, Lake Alfred, FL.

Yokomi RK. 1995. Why the concern about spread of brown citrus aphids into new citrus areas? pp. 27–31. In Lee R, Roca-PeAa M, Niblett CL, Ocoa F, Garnsey SM, Yokomi RK, Lastra R (editors). Citrus tristeza virus and the brown citrus aphid in the Caribbean Basin Management strategies. Proceedings of the Third International Workshop, University of Florida, Lake Alfred, FL.

Yokomi RK, Lastra R, Stoetzel MB, Damsteegt VC, Lee RF, Garnsey SM, Gottwald TR, Rocha PeAa MA, Niblett CL. 1994. Establishment of the brown citrus aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) in Central America and the Caribbean Basin and transmission of citrus tristeza virus. Journal of Economic Entomology 87: 1078–1085.