Why does Florida experience such high numbers of mosquitoes after a hurricane?

Mosquitoes go through four developmental stages during their life: eggs, larvae, pupae, and adults. Dozens of species of mosquitoes reside in Florida, and the different species have differing means of surviving.

In addition to many environmental variables, there are two biological attributes related to mosquito egg-laying that contribute to the numbers of mosquitoes seen and felt during a post-hurricane period. The attributes separate mosquitoes on the basis of the conditions in which they lay their eggs. The two groups are floodwater mosquitoes and standing-water mosquitoes.

Floodwater Mosquitoes

Many people associate mosquitoes strictly with standing water, with the belief that mosquitoes have to have water to lay their eggs. The fact is, mosquito eggs need water to hatch—but some species lay their eggs in moist soil (not standing water) and actually the eggs need to dry out before they can hatch. These mosquitoes are the "floodwater" species.

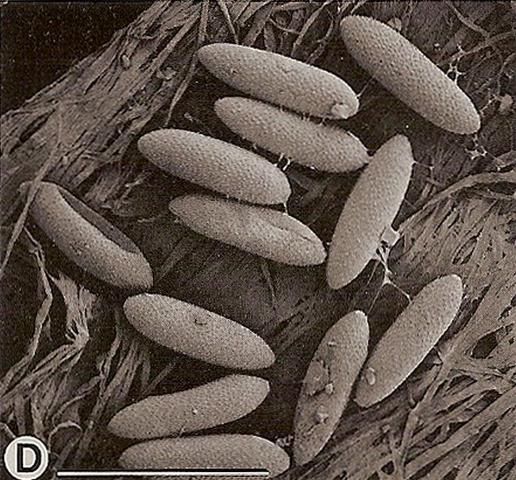

Credit: S. McCann (UF/IFAS/FMEL)

As far back as one year from the time the floodwater mosquitoes are noticeable, the adult female mosquitoes were flying around, feeding on blood, and laying eggs (one female floodwater mosquito has the potential to lay 200 eggs per batch) in moist areas of pastures, citrus furrows, salt-marsh, and swales. These moist areas eventually dry out, and the mosquito eggs also dry and become encased in the cracks and crevices of the dried mud. Because of their unique biology, the eggs need to dry out before they can hatch into larvae. The eggs survive in the dry soil through the winter and spring, and then with rains from storms or hurricanes, those areas are inundated with water. The water that reaches the eggs provides a cue to hatch.

One can consider the potential extent of this habitat by thinking about how much land in Florida is pasture, citrus grove, or large expanses of uninhabited flat land. There are estimates of the number of mosquito eggs in a floodwater habitat between 0.7 and 1.3 million eggs per acre. Yes—per acre. If only a small percentage of those eggs hatched and survived to the adult stage, the number of adult mosquitoes flying around looking for blood at one time is almost incomprehensible.

Unfortunately, for those who are diligent about dumping water and cleaning up containers around their home, this type of local and small scale effort will not contribute much impact to reducing mosquitoes in the floodwater sites.

Standing Water Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes that are not in the floodwater group lay their eggs on standing water. Another difference between the two groups is that mosquito eggs in this category cannot withstand drying out. If the water dries up, or the egg gets stranded on the grass or soil, the egg dries and that will be the end; it will not hatch into a larva.

Credit: S. McCann (UF/IFAS/FMEL)

Females will lay their eggs on the water surface and the eggs will typically hatch in about 24 hours. Water is necessary to complete the life cycle, and soon the larva will change into a pupa and then emerge into an adult that will soon be hungry for blood. After the newly emerged female mates and finds a blood source, she can start the cycle all over again by laying her eggs on the standing water.

The Double Whammy

The combination of the egg-laying habits of these two groups of mosquitoes provides for a double whammy put in place by activity that occurred with hurricanes and tropical storms. When dry areas flood, the floodwater mosquito eggs hatch. When the floodwater has nowhere to go, the standing-water mosquitoes have more places to lay their eggs.

What Can Individuals Do To Relieve Mosquito-Biting Pressure?

Draining water is recommended for reducing mosquito habitats. But just how are you going to drain an acre full of water? The recommendation to dump the water applies to mosquitoes that lay their eggs in water-holding containers that individual homeowners have control over, such as pet dishes, vases, and cans. The advice is good for average, everyday situations—that is, the times when Florida has not been in the path of a hurricane or tropical storm. The mosquito habitats resulting from the types of rain events from hurricanes are too vast for an individual homeowner to attempt to impact. It is best to leave the source reduction and treatment of such vast water sources to the mosquito control agencies.

In counties that have mosquito-control programs, help may not be immediate because there are such large areas that may need to be treated. And it may not be permanent—remember that mosquitoes fly. Even though an area may be treated to knock down the biting mosquitoes, there will likely be re-infestations from other areas due to the wide-spread flooding in the state.

The most effective way to stop a mosquito from biting is by wearing an effective mosquito repellent on the exposed portions of the body. Protective clothing is often mentioned as a deterrent, but during the very warm summer and fall evenings in Florida, especially for those who may not have electricity, long sleeves and long pants may not be practical.

The second best advice is to stay indoors. Check for damage to your home from the storms that may not be obvious. Look for holes in window and door screens; check for any newly formed open areas around your roof and windows where mosquitoes may gain access indoors; if you have pets that have access to both indoors and outdoors, brush their coats with your hands before they come inside to remove any mosquitoes that may be hanging on.