Introduction

Culex quinquefasciatus Say, commonly known as the southern house mosquito, is a medium-sized brown mosquito that exists throughout the tropics and the lower latitudes of temperate regions. This species is found in the southern United States and is present throughout Florida. This nighttime-active, opportunistic blood feeder is a vector of many pathogens, several of which affect humans. Throughout much of the southern United States, Culex quinquefasciatus is the primary vector of St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEv). Culex quinquefasciatus also transmits West Nile virus (WNv).

Synonymy

Culex quinquefasciatus Say (1823)

Culex pungens Wiedemann, 1828 (ITIS 2007)

Culex fatigans Wiedemann, 1828 (Bates 1949)

Culex auestuans Wiedemann, 1828 (WRBU)

Culex acer Walker, 1848 (WRBU)

Culex cingulatus Doleschall, 1856 (WRBU)

Distribution

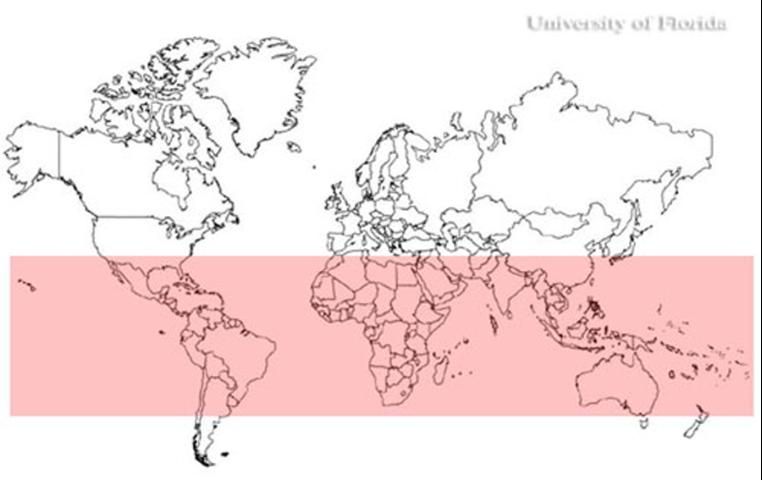

Culex quinquefasciatus is a sub-tropical species usually found within the latitudes 36° N and 36° S. However, in the United States between 36° N and 39° N there is a broad hybrid zone where Cx. quinquefasciatus freely mates with Culex pipiens Linnaeus, which is usually not found south of 39° N. Mating between these two members of the Culex pipiens complex produces viable offspring within the hybrid zone. The extent of the hybridization is extensive and, as a result, the members are sometimes considered to be subspecies, Cx. pipiens quinquefasciatus and Cx. p. pipiens respectively. Culex quinquefasciatus is found in North America, South America, Australia, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and New Zealand.

In the United States, this species ranges from Virginia across the southern plains to southern California, and from as far north as southern Iowa, south to Texas and Florida. There are reports of Cx. quinquefasciatus as far north as Indiana in the United States. The species has also been collected in Hawaii (Barr 1957). In Florida, Cx. quinquefasciatus is found in all 67 counties.

Credit: Stephanie Hill, UF/IFAS

Description

Adults

Adult Cx. quinquefasciatus vary from 3.96 to 4.25 mm in length (Lima et al. 2003). The mosquito is brown with the proboscis, thorax, wings, and tarsi darker than the rest of the body. The head is light brown with the lightest portion in the center. The antennae and the proboscis are about the same length, but in some cases the antennae are slightly shorter than the proboscis. The flagellum has thirteen segments that have few to no scales (Sirivanakarn et al. 1987). The scales of the thorax are narrow and curved. The abdomen has pale, narrow, rounded bands on the basal side of each tergite. The bands barely touch the basolateral spots taking on a half-moon shape (Darsie and Ward 2005).

Credit: James Newman, UF/IFAS

Eggs

Credit: Stephanie Hill, UF/IFAS

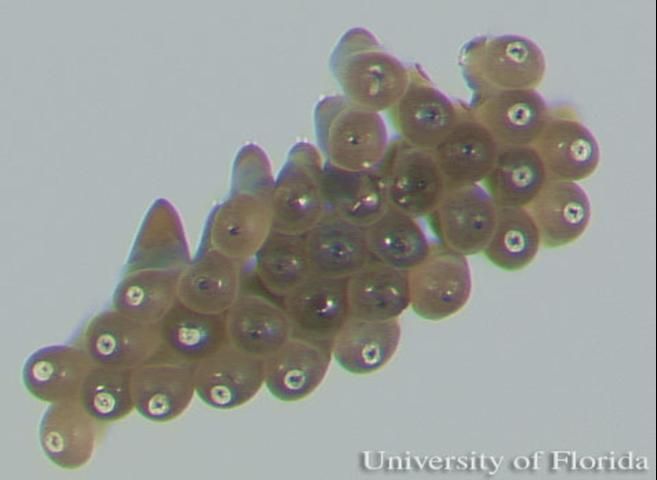

Common to the Culex genus, the eggs of Cx. quinquefasciatus are laid in oval rafts loosely cemented together with 100 or more eggs in a raft, which will normally hatch 24 to 30 hours after being oviposited (Bates 1949).

Larvae

The larval head is short and stout, becoming darker toward the base. The mouth brushes have long yellow filaments that are used for filtering organic materials. The abdomen consists of eight segments, the siphon, and the saddle. Each segment has a unique setae pattern (Sirivanakarn and White 1978). The siphon is on the dorsal side of the abdomen, and in Cx. quinquefasciatus the siphon is four times longer than it is wide with multiple setae tufts (Darsie and Morris 2000). The saddle is barrel shaped and located on the ventral side of the abdomen with four long anal papillae protruding from the posterior end (Sirivanakarn and White 1978).

Credit: Stephanie Hill, UF/IFAS

Pupae

Similar to other mosquito species, Cx. quinquefasciatus pupae are comma shaped and consist of a fused head and thorax (cephalothorax and an abdomen). The cephalothorax color varies with habitat and darkens on the posterior side. The trumpet, which is used for breathing, is a tube that widens and becomes lighter in color as it extends away from the body. The abdomen has eight segments. The first four segments are the darkest, and the color lightens towards the posterior. The paddle, at the apex of the abdomen, is translucent and robust with two small setae on the posterior end (Sirivanakarn and White 1978).

Credit: Stephanie Hill, UF/IFAS

Life Cycle

Gravid Cx. quinquefasciatus females fly during the night to nutrient-rich standing water where they will lay their eggs. They will oviposit in waters ranging from waste water areas to bird baths, old tires, or any container that holds water. If the water evaporates before the eggs hatch or the larvae complete their life cycle, they die.

The larvae feed on biotic material in the water and require between five to eight days to complete their development at 30°C (Gerberg et al. 1994). The larvae progress through four larval instars, and towards the end of the fourth instar they stop eating and molt to the pupal stage. Following 36 hours at 27°C the adults emerge from the pupal stage (Gerberg et al. 1994). The time of development under natural conditions for all stages is variable and dependent on temperature.

Both males and females take sugar meals from plants. Following mating, the female seeks a blood meal. Culex quinquefasciatus are opportunistic feeders, feeding on mammals and/or birds throughout the night. Males survive only on sugar meals, while the female will take multiple blood meals. After a female mosquito digests the blood meal and the eggs develop, she finds a suitable place to lay her eggs, and the cycle begins again. A single female can lay up to five rafts of eggs in a lifetime (Gerberg et al. 1994). The number of eggs per raft varies with climatic conditions.

Credit: Sean McCann

Medical Importance

Culex quinquefasciatus is a vector of many pathogens of humans and both domestic and wild animals. Viruses transmitted by this species include WNv, SLEv, and Western equine encephalitis virus (WEEv). Culex quinquefasciatus is the principal vector of SLEv in the southern United States. The virus increases its numbers in birds and then infects mosquitoes feeding on birds during the bird nesting season in the spring. The mosquito may then transmit the virus to humans. St. Louis encephalitis is age-dependent, affecting older humans more than the young. Symptoms of the disease are flu-like and can range from fever and headaches to stiffness and confusion. After a period of several days the brain may begin to swell, accompanied by depression, extreme excitement, sleepiness, or sleeplessness (CDC June 2007). Humans do not develop high levels of the virus in the blood and, therefore are considered dead-end hosts unable to infect mosquitoes (Foster and Walker 2002). In Florida, major St. Louis encephalitis epidemics occurred in 1959, 1961, 1962, 1977, and 1990 (Day and Stark 2000). Other epidemics in the United States include Colorado 1985, Arkansas 1991, New York 1999, and Louisiana 2001 (CDC October 2007).

Although Cx. quinquefasciatus is not considered the likely primary vector of WNv in Florida, it likely plays an important role in maintaining the virus within bird populations and is capable to transmitting it to humans. For more information on West Nile virus in Florida, see the UF/IFAS publication West Nile Virus.

Outside the United States, Cx. quinquefasciatus is responsible for transmitting the filarial nematode, Wuchereria bancrofti (Tropical Africa and Southeast Asia), and Rift Valley fever virus (RVF) (Africa) (Foster and Walker 2002). Wuchereria bancrofti is a filarial nematode that can cause lymphatic filariasis. Currently, worldwide there are approximately 120 million cases of lymphatic filariasis (WHO 2000). The mosquito picks up the microfilaria from an infected vertebrate. The nematode develops inside the mosquito and is passed on to another vertebrate (Foster and Walker 2002). RVF has been responsible for major epidemics in Africa and Asia. The World Health Organization monitors outbreaks of RVF. Between 2000 and 2010, there were outbreaks in Kenya, Madagascar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, and Yemen (World Health Organization 2012).

Management

Cultural Control

Personal protection, reduction of larval habitats, and chemical control are the best ways to reduce mosquito bites and therefore the transmission of mosquito-borne pathogens. Because Cx. quinquefasciatus feeds at night, long sleeve shirts and insect repellent are recommended for outside nighttime activity. Reducing the amount of outside activity also lowers the risk of Cx. quinquefasciatus bites.

Culex quinquefasciatus is dependent upon humans for the creation of its nutrient-rich aquatic habitats. It is essential to reduce or eliminate this type of aquatic environment. Around the home this can be done by not over watering plants, changing water in pet water dishes frequently, changing water in bird baths at least once a week, removing unnecessary water-holding containers, and keeping ponds stocked with mosquito fish (Kern 2007). Water-holding containers that cannot be removed can be covered or turned upside down, old tires need to be removed, and drainage ditches need to be kept clear of debris that will obstruct flow.

Large man-made aquatic habitats such as storm-water catch basins and waste water containers should be eliminated or reduced (O'Meara 2014).

Chemical Control

Insecticides can be used to control larvae and adults. Larvicides are applied to bodies of water near where the larvae are concentrated. This method reduces the greatest number of immature mosquitoes with the least amount of pesticide. Adulticides are used to quickly reduce the population of adult mosquitoes in an area. In general, mosquito resistance to specific insecticides may reduce the effectiveness of chemical control. Some chemicals require a licensed pesticide applicator to perform the application. Before proceeding with a chemical control, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office or Mosquito Control District (AMCA 2005). In Florida, you can find your local UF/IFAS Extension office through the UF/IFAS listing of those offices.

Selected References

AMCA. 2005. Mosquito Information: Control. American Mosquito Control Association. https://www.mosquito.org/page/control (June 2019)

Barr AR. 1957. "The distribution of Culex p. pipiens and C. p. quinquefasciatus in North America." Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 6: 153–165.

Bates M. 1949. The Natural History of Mosquitoes. Macmillian Company. New York, NY. 379 pp.

Belkin JN. 1977. "Quinquefasciatus or Fatigans for the tropical (southern) house mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae)." Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 79: 45–52.

CDC. June 2007. CDC answers your questions about St. Louis encephalitis. Center for Disease Control. http://www.cdc.gov/sle/technical/fact.html (14 June 2016).

CDC. October 2007. Saint Louis Encephalitis. Center for Disease Control. http://www.cdc.gov/sle/ (2 June 2009).

Connelly CR. 2006. Common Mosquitoes of Florid. SP 370. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Cutwa-Francis MM, O'Meara GF. 2008. Culex quinquefasciatus. Identification Guide to Common Mosquitoes of Florida. https://fmel.ifas.ufl.edu/mosquito-guide/mosquito-genera-and-species/genus-culex/culex-quinquefasciatus/

Darsie Jr RF, Morris CD. 2000. "Keys to the adult females and fourth-instar larvae of the mosquitoes of Florida (Diptera: Culicidae)." Technical Bulletin of the Florida Mosquito Control Association 1: 148–155.

Darsie Jr RF, Ward RA. 2005. Identification and Geographical Distribution of the Mosquitoes of North America, North of Mexico. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press.

Day JF, Stark LM. 2000. "Frequency of Saint Louis encephalitis virus in humans from Florida, USA: 1990–1999." Journal of Medical Entomology 37: 626–633.

Fonseca DM, Keyghobadi N, Malcolm CA, Mehmet C, Schaffner F, Mogi M, Fleischer RC, Wilkerson RC. 2004. "Emerging Vectors in the Culex pipiens Complex." Science 303: 1535–1538.

Foster WA, Walker ED. 2002. Mosquitoes (Culicidae), pp. 245–249. In Mullen G, Durden L. (editors). Medical and Veterinary Entomology. Academic Press. New York, NY.

Gerberg EJ, Barnard DR, Ward RA. 1994. "Manual for Mosquito Rearing and Experimental Techniques." American Mosquito Control Association Bulletin No. 5: 61–62.

ITIS. 2009. Culex quinquefasciatus Say, 1823. Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=126490 (14 June 2016).

Kern WH. September 2007. Some Small Native Freshwater Fish Recommended for Mosquito and Midge Control in Ornamental Ponds. ENY670 Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN456 (14 June 2016).

King WV, Bradley GH, Smith CN, McDuffie WC. 1960. A Handbook of the Mosquitoes of the Southern United States. Agriculture Handbook No. 173. United States Department of Agriculture. Washington D.C. pp. 118–119.

Lima CA, Almeida WR, Hurd H, Albuquerque CM. 2003. "Reproductive aspects of the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) infected with Wuchereria bancrofti (Spirurida: Onchocercidae)." Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 98: 217–222.

O'Meara GF. 2014. Mosquitoes Associated with Stormwater Detention/Retention Areas. ENY627. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg338 (14 June 2016).

Savage HM, Anderson M, Gordon E, McMillen L, Colton L, Charnetzky D, Delorey M, Aspen S, Burkhalter K, Biggerstaff BJ, Godsey M. 2006. "Oviposition activity patterns and West Nile virus infection rates for members of the Culex pipiens complex, at different habitat types within the hybrid zone, Shelby County, TN, 2002 (Diptera: Culicidae)." Journal of Medical Entomology 43: 1227–1238.

Sirivanakarn S, White GB. 1978. "Neotype designation of Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae)." Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 80: 360–372.

Shroyer DA, Rey JR. 2014. Saint Louis Encephalitis: A Florida Problem. FMELMG337 Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/MG337 (14 June 2016).

WRBU. (undated). Adult Culex quinquefasciatus. The Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit. http://www.wrbu.org/mqID/mq_medspc/AD/cxqui_hab.html

World Health Organization. (September 2000). "Lymphatic filariasis." World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/lymphatic_filariasis/en/ (14 June 2016).

World Health Organization. 2012. Global Alert and Response. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/riftvalleyfev/en/index.html (14 June 2016).