Plant-parasitic nematodes are small microscopic roundworms that live in the soil and attack the roots of plants. Crop production problems induced by nematodes therefore generally occur as a result of root dysfunction; nematodes reduce rooting volume and the efficiency with which roots forage for and use water and nutrients. Many different genera and species of nematodes can be important to crop production in Florida. In many cases a mixed community of plant-parasitic nematodes is present in a field, rather than having a single species occurring alone. Okra is infamous for its susceptibility to root-knot nematodes; it is also extremely sensitive to sting nematodes. Because of this, okra should not be planted in land known to have severe problems with these nematodes in recent crops. Do not plant in any field where these nematodes are likely to occur without treating the soil with a fumigant nematicide listed on this page or a multipurpose fumigant listed in other documents at this site. Nematode infestation commonly causes very irregular growth, with production reduced and delayed. The host range of root-knot and sting nematodes, as with others, includes many different weeds and most if not all of the commercially grown vegetables within the state. Yield reductions can be extensive but vary significantly between plant and nematode species. In addition to the direct crop damage caused by nematodes, many of these species have also been shown to predispose plants to infection by fungal or bacterial pathogens or to transmit virus diseases, which contribute to additional yield reductions.

General IPM Considerations

Integrated pest management (IPM) for nematodes requires 1) determining whether pathogenic nematodes are present within the field; 2) determining whether nematode population densities are high enough to cause economic loss; and 3) selecting a profitable management option. Attempts to manage nematodes may be unprofitable unless all of the above IPM procedures are considered and carefully followed. Similarly, some management methods pose risk to people and the environment. Therefore it is important to know that their use is justified by actual conditions in a field and that certified applicators are overseeing their use.

Biology and Life History

Most species of plant-parasitic nematodes have a relatively simple life cycle consisting of the egg, four larval stages, and the adult male and female. Development of the first-stage larva occurs within the egg, where the first molt occurs. Second-stage larvae hatch from eggs to find and infect plant roots or, in some cases, foliar tissues. Host finding or movement in soil occurs within surface films of water surrounding soil particles and root surfaces. Depending on species, feeding will occur along the root surface or, in some species like root-knot, young larval stages will invade root tissue, establishing permanent feeding sites within the root. Second-stage larvae will then molt three times to become adult males or females. For most species of nematodes, as many as 50–100 eggs are produced per female, but in some such as root-knot, upwards of 2000 may be produced (Figure 2). Under suitable environmental conditions, the eggs hatch and new larvae emerge to complete the life cycle within 4 to 8 weeks, depending on temperature. Nematode development is generally most rapid within an optimal soil temperature range of 70 to 80°F.

Symptoms

Typical symptoms of nematode injury can involve both aboveground and belowground plant parts. Foliar symptoms of nematode infestation of roots generally involve stunting and general unthriftiness, premature wilting and slow recovery to improved soil moisture conditions, leaf chlorosis (yellowing), and other symptoms characteristic of nutrient deficiency. An increased rate of ethylene production, thought to be largely responsible for symptom expression in tomato, has been shown to be closely associated with root-knot nematode root infection and gall formation. Plants exhibiting stunted or decline symptoms usually occur in patches of nonuniform growth rather than as a overall decline of plants within an entire field (Figure 1).

The time in which symptoms of plant injury occur is related to nematode population density, crop susceptibility, and prevailing environmental conditions. For example, under heavy nematode infestation, crop seedlings or transplants may fail to develop, maintaining a stunted condition, or die, causing poor or patchy stand development. Under less severe infestation levels, symptom expression may be delayed until later in the crop season after a number of nematode reproductive cycles have been completed on the crop. In this case aboveground symptoms will not always be readily apparent early in crop development, but with time and reduction in root system size and function, symptoms become more pronounced and diagnostic.

Root symptoms induced by sting or root-knot nematodes can oftentimes be as specific as aboveground symptoms. Sting nematode can be very injurious, causing infected plants to form a tight mat of short roots, oftentimes assuming a swollen appearance. New root initials generally are killed by heavy infestations of the sting nematode, a symptom reminiscent of fertilizer salt burn. Root symptoms induced by root-knot cause swollen areas (galls) on the roots of infected plants (Figure 2). Gall size may range from a few spherical swellings to extensive areas of elongated, convoluted, tumorous swellings that result from exposure to multiple and repeated infections. Symptoms of root galling can in most cases provide positive diagnostic confirmation of nematode presence, infection severity, and potential for crop damage.

Damage

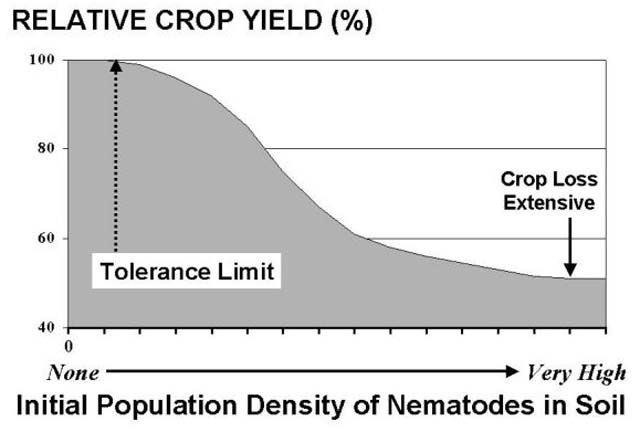

For most crop and nematode combinations the damage caused by nematodes has not been accurately determined. Most vegetable crops produced in Florida are susceptible to nematode injury, particular by root-knot and sting nematodes. Plant symptoms and yield reductions are often directly related to preplant infestation levels in soil and to other environmental stresses imposed upon the plant during crop growth (Figure 3). As infestation levels increase so then does the amount of damage and yield loss. In general, the mere presence of root-knot or sting nematodes suggests a potentially serious problem, particularly on sandy ground during the fall when soil temperatures favor high levels of nematode activity. At very high levels, typical of those that might occur under doubling cropping, plants may be killed. Older transplants, unlike direct seed, may tolerate higher initial population levels without incurring as significant a yield loss.

Field Diagnosis and Sampling

Because of their microscopic size and irregular field distribution, soil and root tissue samples are usually required to determine whether nematodes are causing poor crop growth or to determine the need for nematode management. For nematodes, sampling and management is a preplant or postharvest consideration because if a problem develops in a newly planted crop there are currently no postplant corrective measures available to rectify the problem completely once the nematode becomes established. Nematode density and distribution within a field must, therefore, be accurately determined before planting, guaranteeing that a representative sample is collected from the field. Nematode species identification is currently only of practical value when rotation schemes or resistant varieties are available for nematode management. This information must then be coupled with some estimate of the expected damage to formulate an appropriate nematode control strategy.

Advisory or Predictive Sample (Prior to Planting)

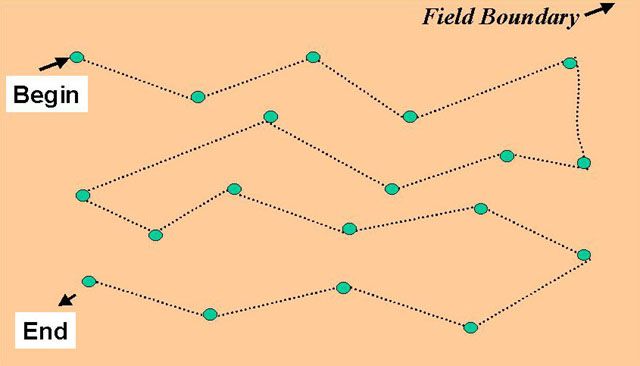

Samples taken to predict the risk of nematode injury to a newly planted crop must be taken well in advance of planting to allow for sample analysis and treatment periods if so required. For best results, sample for nematodes at the end of the growing season, before crop destruction, when nematodes are most numerous and easiest to detect. Collect soil and root samples from 10 to 20 field locations using a cylindrical sampling tube, or if unavailable, a trowel or shovel (Figure 4). Since most species of nematodes are concentrated in the crop rooting zone, samples should be collected to a soil depth of at least 6 to 10 inches. Plant-pathogenic nematodes can be deeply distributed throughout the soil profile well below the typical sampling depth and zones of root growth, and have the capability to move upward to infest plant roots. In this scenario, samples procured from surface soil horizons may not adequately describe nematode populations and potential threats to crop growth and yield. For practicality, sample in a regular pattern over the area, emphasizing removal of samples across rows rather than along rows (Figure 5). One sample should represent no more than 10 acres for relatively low-value crops and no more than 5 acres for high value crops. Fields that have different crops (or varieties) during the past season or that have obvious differences either in soil type or previous history of cropping problems should be sampled separately. Sample only when soil moisture is appropriate for working the field, avoiding extremely dry or wet soil conditions.

Diagnostics on Established Plants

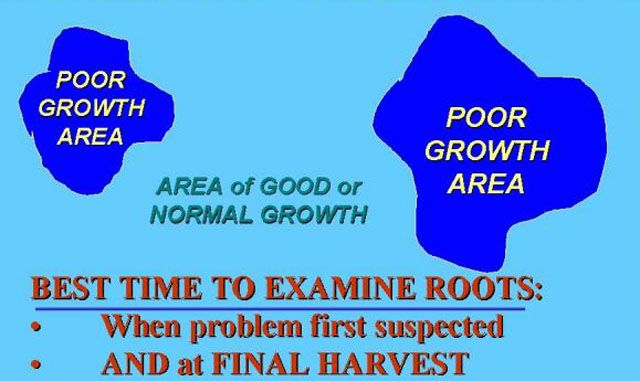

Roots and soil cores should be removed to a depth of 6 to 10 inches from 10 to 20 suspect plants within areas of poor growth. Avoid dead or dying plants, since dead or decomposing roots will often harbor few nematodes. For seedlings or young transplants, excavation of individual plants may be required to insure sufficient quantities of infested roots and soil. Submission of additional samples from adjacent areas of good growth should also be considered for comparative purposes (Figure 6).

For either type of sample, once all soil cores or samples are collected, the entire sample should then be mixed thoroughly, but carefully, and a 1 to 2 pint subsample removed to an appropriately labeled plastic bag. Remember to include sufficient feeder roots. The plastic bag will prevent drying of the sample and guarantee an intact sample upon arrival at the laboratory. Never subject the sample(s) to overheating, freezing, drying, or to prolonged periods of direct sunlight. Samples should always be submitted immediately to a commercial laboratory or to the University of Florida Nematode Assay Laboratory for analysis. If sample submission is delayed, then temporary refrigerated storage at temperatures of 40 to 60°F is recommended.

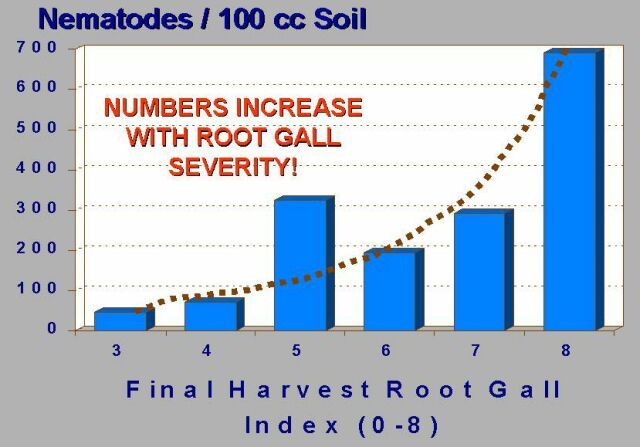

Recognizing that the root-knot nematode causes the formation of large swollen areas or galls on the root systems of susceptible crops, relative population levels and field distribution of this nematode can be largely determined by simple examination of the crop root system for root gall severity (Figure 7). Root gall severity is a simple measure of the proportion of the root system that is galled. Immediately after final harvest, a sufficient number of plants should be carefully removed from soil and examined to characterize the nature and extent of the problem within the field. In general, soil population levels increase with root gall severity (Figure 8). This form of sampling can in many cases provide immediate confirmation of a nematode problem and allows mapping of current field infestation. As inferred previously, the detection of any level of root galling usually suggests a nematode problem for planting a susceptible crop, particularly within the immediate areas from which the galled plant(s) was recovered.

General Management Considerations

Currently nematode management considerations include crop rotation of less susceptible crops or resistant varieties, cultural and tillage practices, use of transplants, and preplant nematicide treatments. Where practical, these practices are generally integrated into the summer or winter 'off-season' cropping sequence. It should be recognized that not all land management and cultural control practices are equally effective in controlling plant parasitic nematodes and varying degrees of nematode control should be expected. These methods, unlike other chemical methods, tend to reduce nematode populations gradually through time. Farm specific conditions, such as soil type, temperature, and moisture, can be very important in determining whether different cultural practices can be effectively utilized for nematode management. In most cases, a combination of these management practices will substantially reduce nematode population levels, but will rarely bring them below economically damaging levels. This is especially true of lands that are continuously planted to susceptible crop varieties. In these cases some form of pesticide assistance will still usually be necessary to improve crop production. For further explanation and details of general management considerations in this document, see the section called "Nematode Management for Vegetable Crops in Florida."

Chemical Control

Nonfumigant Nematicides

All of the nonfumigant nematicides (Table 1) currently registered for use in okra are soil applied. Nimitz, a new nonfumigant nematicide that became commercially available in 2015, is still actively under assessment in field trial evaluations. All of the nonfumigant nematicides must be incorporated with soil or carried by water into soil to be effective. These compounds must be uniformly applied to soil, targeting the application toward the future rooting zone of the plant, where they will contact nematodes or, in the case of systemics, in areas where they can be readily absorbed and taken up into the plant. Placement and incorporation within the top 3 to 6 inches of soil should provide a zone of protection for seed germination, transplant establishment, and protect initial growth of plant roots from seeds or transplants. Most studies that have been performed in Florida and elsewhere to evaluate nonfumigant nematicides have not always been consistent, either for controlling intended pests or for obtaining consistent economic returns to the grower, particularly when compared with conventional preplant mulched fumigation with a broadspectrum fumigant nematicide. As the name implies, they are specific to nematodes, have limited residual activity, and require integrated use of other cultural or chemical pest control measures to manage other weed and disease pests. Many are reasonably mobile and are readily leached in our sandy, low organic soils, thus requiring special consideration to irrigation practices and management.

Fumigant Nematicides

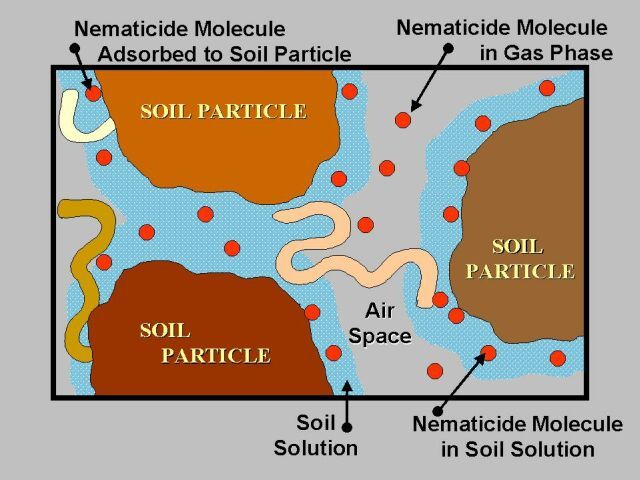

In Florida, the use of broadspectrum fumigants (Table 2 and 3) effectively reduces nematode populations and increases vegetable crop yields, particularly when compared with nonfumigant nematicides. Most studies that have been performed in Florida and elsewhere to evaluate non-fumigant nematicides have not always been consistent, either for controlling intended pests or for obtaining consistent economic returns to the grower, particularly when compared with conventional preplant mulched fumigation with a broadspectrum fumigant nematicide (Figure 9). Since these products must diffuse through soil as gases to be effective (Figure 10), the most effective fumigations occur when the soil is well drained, in seedbed condition, and at temperatures above 60°F. Fumigant treatments are most effective in controlling root-knot nematode when residues of the previous crop are either removed or allowed to decay. When plant materials have not been allowed to decay, fumigation treatments may decrease but not eliminate populations of root-knot nematodes in soil, particularly nematodes within the egg stage. Crop residues infested with root-knot nematode may also shelter soil populations to the extent that significantly higher rates of application may be required to achieve nematode control. To avoid these problems, growers are advised to plan crop destruction and soil cultivation practices well in advance of fumigation to insure decomposition of plant materials before attempting to fumigate.

In general, the use of soil fumigants has been more consistently effective than non-fumigants for control of root-knot and sting nematodes in Florida. In the fine sands of Florida, dry soils (no more than or less than 12 to 15% available soil moisture content) are considered favorable for soil fumigation. In addition to buffer zones, the new fumigant labels also outline a new series of mandatory Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) to reduce emissions and bystander exposures. These have become new mandatory label requirements effective January 1, 2012. The new GAPs that must be followed during all fumigant applications and that are posing Florida growers significant difficulties include changes in 1) Soil Preparation: "Soil shall be properly prepared" and "field trash must be properly managed." Residue from a previous crop must be worked into the soil to allow for decomposition prior to fumigation; and 2) Soil Moisture: In general, the new soil fumigant labels will indicate that soil moisture in the top nine inches of soil must be between 50% to 80% of soil capacity (field capacity) immediately prior to fumigant application, subject to the exception where soil moisture must exceed field capacity to form a bed (e.g. certain regions in Florida where soil capacity may exceed the 80% allocated above). Following EPA reregistration, the new fumigant labels which went into effect December 1, 2012 detail additional use restrictions based on soil characteristics, buffer zones, requirements for Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), mandatory good agricultural practices (GAPs), applicator training certification, and other new rate modifying recommendations.

All of the fumigants are phytotoxic to plants and as a precautionary measure should be applied at least 3 weeks before crops are planted. When applications are made in the spring during periods of low soil temperature, these products can remain in the soil for an extended period, thus delaying planting or possibly causing phytotoxicity to a newly planted crop (Figure 11 and Figure 12). Field observations also suggest rainfall or irrigation that saturates the soil after treatment tends to cause the soil to retain phytotoxic residues for longer periods, particularly in deeper soil layers.

Summary

In summary, nematode control measures can be conveniently divided into two major categories: cultural and chemical control measures. None of these measures should be relied upon exclusively for nematode management. Rather, when practicality and economics permit, each management procedure should be considered for use in conjunction with all other available measures for nematode control and used in an integrated program of nematode management. In addition to nematodes, many other pests can cause crop damage and yield losses that further enforce the development of an overall Integrated Pest Management (IPM) program, utilizing all available chemical and nonchemical means of reducing pest populations to subeconomic levels. An IPM approach further requires that growers attempt to monitor or scout fields for pest densities at critical periods of crop growth.

For an explanation of Table 1 in this document, see the section called "Explanation of Rates Listed in Nematicide Tables for Vegetable Crops" found in Nematode Management in Commercial Vegetable Production.