Beach mice live on beaches in Florida and Alabama in dunes that are located just above the high-tide line (Figure 1). A variety of animals live with beach mice in these habitats, including six-lined racerunners (Aspidoscelis sexlineata), monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus), and coachwhip snakes (Coluber flagellum). Because beach mice occur only in dune habitats, they are at high risk of extinction if this habitat is destroyed.

Currently, most subspecies of beach mice are considered threatened or endangered. The main threats to beach mice are linked to humans and coastal development. Construction of homes and condominiums has caused destruction of dune habitats. Other factors associated with development, such as artificial light and non-native predators, also affect beach mice. For example, beach mice forage less in areas illuminated by artificial lights and hunting of beach mice by domestic cats can reduce their populations. Continuing conservation efforts to protect beach mice faced with these threats will help ensure survival of this species.

Credit: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Distribution and Status

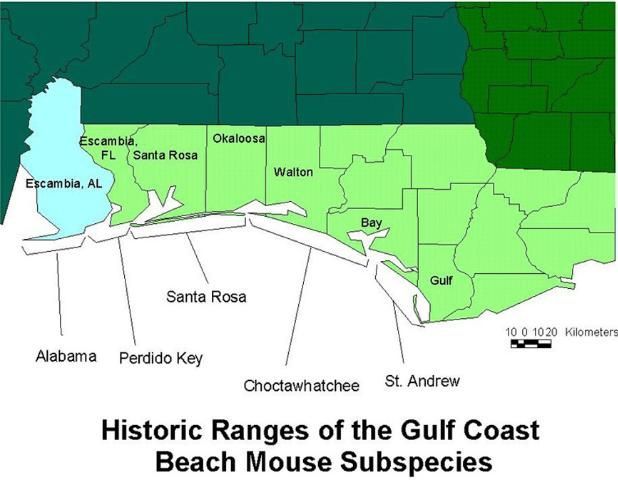

Beach mice comprise eight subspecies of the oldfield mouse (Peromyscus polionotus). The eight subspecies include five on the Gulf Coast and three (historically) on the Atlantic Coast. The five Gulf Coast subspecies are found in geographically distinct populations on barrier islands, keys, or coastal peninsulas between Mobile Bay, Alabama, and Cape San Blas, Florida (Figure 2).

Credit: Kathryn Smith

Gulf Coast subspecies (5)

- Alabama beach mouse (P. p. ammobates)

- Perdido Key beach mouse (P. p. trissyllepsis)

- Santa Rosa beach mouse (P. p. leucocephalus)

- Choctawhatchee beach mouse (P. p. allophrys)

- St. Andrew beach mouse (P. p. peninsularis)

Of the remaining three subspecies, one has already been declared extinct—the Pallid beach mouse (P. p. decoloratus). The two surviving Atlantic Coast subspecies range along Florida's Atlantic coast between Ponte Vedra Beach and Hollywood Beach.

Remaining Atlantic Coast subspecies (2)

- Anastasia Island beach mouse (P. p. phasma)

- Southeastern beach mouse (P. p. niveiventris)

Currently, all beach mice subspecies except the Santa Rosa beach mouse are listed as threatened or endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Description

Beach mice are small, pale mice with large ears and dark eyes (Figure 1 and Figure 5). Males and non-reproductive females average 12.5 g (0.44 oz) in weight. Pregnant females may exceed 20 g (0.71 oz). The pale coloration of beach mice is believed to be an adaptation to the white sands of their coastal habitat. Beach mice exhibit a hint of brownish or grayish coloration across their backs but are generally much lighter in color than other mice. The amount and hue of coloration varies among subspecies, with the Santa Rosa beach mouse being the palest in color and the Alabama beach mouse having the most pigmented fur. Subspecies can also be distinguished by the extent to which coat coloration extends onto their faces and down their sides and by the presence or absence of a tail stripe.

Life History and Behavior

Breeding and Dispersal

Beach mice are believed to have a monogamous mating system where one male mates with one female. Mating among beach mice peaks in the winter but continues year-round if food is available. Once pregnant, the mother gives birth in about 23 days. Females give birth to an average of four pups per litter and are ready to breed again within 24 hours. Beach mice live 9 months to a year in the wild. Young mice have the ability to disperse several kilometers (1 km = 0.62 mile) from their birthplace to establish their own home ranges.

Home Range and Habitat Use

Home range size varies among subspecies but averages about 5000 m2 (1.24 acres). Individual home ranges commonly overlap. Beach mice often maintain multiple burrows within their home range. Burrows are used for sleeping, nesting, feeding, caching seeds, or as shelter from predators. Burrows have a 1–2-inch triangular opening and a 2–3-foot tunnel leading to a main chamber. On the other side of the chamber, mice excavate a second tunnel that ends just below the surface of the sand. This serves as an escape tunnel from predators. If the burrow is disturbed, the resident mouse will often burst through this escape hatch. Burrows are occupied and maintained by a male-female pair or by a female and her pups.

Beach mice prefer to construct their burrows in mature, sparsely vegetated dunes adjacent to the high tide line (primary dunes; Figure 3) and the more densely vegetated dunes farther inland (secondary dunes). Sea oats (Uniola paniculata), dune panic grass (Panicum amarum), and bluestem (Schizachyrium maritimum) are the dominant plant species in these areas. Most foraging activity occurs in primary and secondary dunes, but mice also use other areas within the dune system. Seasonally wet areas between primary and secondary dune systems (called "swales") often contain a thick cover of sedges (Cyperus spp.), rushes (Juncus spp.), and salt grass (Distichlis spicata). Mice use these densely vegetated swales to move between primary and secondary dune habitats and occasionally excavate burrows at the edges of swales.

Credit: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Beach mice also forage and build burrows in the "scrub dunes" found on the bay side of islands (Figure 4). Scrub dunes are dominated by sand live oak (Quercus geminata), myrtle oak (Quercus myrtifolia), dwarf magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), sand pine (Pinus clausa), and false rosemary (Ceratiola ericoides). Scrub dunes are protected from storms by primary and secondary dunes. Thus, they play a key role in providing safe habitat for beach mice when hurricanes disturb or flatten the primary dunes nearer the beach.

Credit: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Activity and Diet

Beach mice are active at night (nocturnal), spending the day sleeping in their burrows. At nightfall mice emerge from their burrows (often in pairs) and forage on seeds and fruits of beach plants and on insects. Mice gather seeds that have fallen or blown onto the sand or climb plant stems to harvest attached seed heads. Sea oats make up a large part of a beach mouse's diet (Figure 5). Based on seasonal availability, beach mice also feed on bluestem, ground cherry (Physalis angustifolia), seabeach evening primrose (Oenothera humifusa), beach pea (Galactia spp.), dune spurge (Chamaesyce ammannioides), jointweed (Polygonella gracilis), seashore elder (Iva imbricata), and seaside pennywort (Hydrocotyle bonariensis). During the night, mice make several trips to and from their burrows and store seeds in their burrows.

Credit: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Conservation and Management Issues

Loss of Dune Habitat

Because of their specific habitat needs, beach mice are in danger of extinction. Both humans and natural environmental factors pose risks for beach mice. Construction of vacation and retirement homes has destroyed dune habitat, and habitat that remains after development is fragmented and degraded (Figure 6). The threats imposed by commercial and residential development are especially serious on islands that already have a limited amount of habitat due to their small size. Further conversion of dune habitat means that little remains for beach mice to meet their needs. Development also affects the natural instability of the coastal island ecosystem. On undeveloped coastal islands, the preferred dune habitat of beach mice is maintained by a dynamic cycle of storm disturbance and subsequent dune regeneration. On islands with extensive development, human-made structures hinder rates of natural, post-hurricane dune regeneration. This problem is made worse by frequent, intense hurricanes.

Credit: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

After a hurricane, dune plants must regenerate. As the plants grow, sand accumulates around the base of their stems and small dunes begin to form. As the plants grow larger, the dunes also grow as the plant root systems hold more sand in place. This process is inhibited when buildings are constructed on the beaches. Native plants are often destroyed during the construction process or are purposely removed to make way for new buildings. When this happens, there are no plants to stabilize the dunes and the dunes can be quickly eroded by the wind or washed away by ocean waves. Following tropical storms and hurricanes, beach communities also often rake up the remains of plant debris on beaches because this debris is considered unsightly. Over time, this practice reduces the amount of food available to beach mice and reduces the plants that would help reform dunes. If left on the beach, these remnant plants can become re-established, helping to grow dunes, and eventually providing food for beach mice. Loss of dune habitat and reduction in dune regeneration rates decrease the availability of safe havens for beach mice. Beach mice populations may have to survive for prolonged periods using marginal burrowing and foraging sites while dunes rebuild. Human development also contributes to the isolation of beach mouse populations. This isolation may restrict recolonization of habitat following the disappearance of local populations.

Introduction of Artificial Light

Beach mice and other species such as sea turtles and marine birds are impacted by light pollution from residential and commercial development. Beach mice reduce the amount of time they spend feeding where there is artificial light and avoid areas with light. This may reduce the amount of habitat available for feeding and ultimately affectthe health of the mice.

Introduced Predators

Beach mice populations are at risk from introduced predators. The domestic cat (Felis catus) and red fox (Vulpes vulpes) hunt beach mice. On islands, beach mice have evolved in the absence of these predators. They lack appropriate predator recognition and avoidance mechanisms and are highly vulnerable to predation by foxes and cats. Many scientists and agencies have cited introduced cats and foxes as a major threat to beach mouse populations and a potential cause of their decline. Removal of these species from beach mouse habitat is now recommended as a conservation practice. Some effort has been made to eradicate cats from Anastasia Island and foxes from Santa Rosa Island. However, no broad campaign has been established to control or eliminate introduced predators from beach mouse habitat as a whole.

Helping Remaining Beach Mice Populations

To help conserve and expand remaining beach mouse populations, biologists and wildlife managers have used translocation and reintroduction techniques. Translocation involves adding beach mice to existing but small populations. Translocated beach mice are generally taken from a large population and are released into a small population. The goal is to strengthen the small population by increasing the number of individuals and the genetic diversity. Reintroduction involves releasing beach mice into an area where beach mice were found in the past (historic range) but are not currently found. When reintroducing beach mice into areas of historical range, biologists hope the beach mice will be able to successfully survive there again and rebuild a stable population.

In 1987, the Florida Game and Freshwater Fish Commission (now called the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) launched a translocation program for the Choctawhatchee beach mouse. A year-long effort resulted in a small but persistent population of the mice at Grayton Beach, Florida. More recently, efforts to reintroduce the Perdido Key beach mouse to the Gulf Islands National Seashore have resulted in a well-established population of mice in that area.

While these efforts have been successful, habitat loss limits the area available for beach mice. More recent efforts focus on dune restoration to revegetate disturbed areas and facilitate re-growth of dunes after storms, thus accelerating the formation of dune habitat suitable for beach mice.

What You Can Do

There are several things you can do to help protect the remaining populations of beach mice. If you are a resident of a beach community, you can reduce the risk of cat predation by keeping cats indoors. Feeding stray cats in beach areas should be avoided as this will encourage stray cats to become permanent residents in beach mouse habitat. In addition, by staying off the dunes while at the beach, you will help to preserve fragile beach mouse habitat. Over time, excessive foot traffic on dunes causes damage to native plants and ultimately destabilizes the dunes. You can reduce destruction of beach mouse habitat by remaining in the designated visitor areas or on designated walkways.

Encouraging the growth of native dune plants around private beach residences is another way to reduce the negative effects that development can have on beach mouse habitat. Also, leave uprooted sea oats plants on the beach after hurricanes so that they can re-establish. Native dune plants such as sea oats, bluestem, evening primrose, and ground cherry can add color and structure to the landscape while providing food for beach mice and encouraging dune regeneration.

Reducing outdoor lighting in areas with dunes can help beach mice. Removing outdoor lights and turning off unnecessary lights are easy ways to help beach mice and other wildlife. Where lights cannot be removed, keep them low and shielded (See Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Wildlife Lighting for more details.)

Finally, share with others what you have learned about beach mice here. The more awareness there is about these unique mice, the more hope there is that beach mice will survive well into the future.

Selected References

Bird, B. L., L. C. Branch, & D. L. Miller. (2004). “Effects of coastal lighting on foraging behavior of beach mice.” Conservation Biology. 18(5):1435-1439.

Extine, Douglas, D. & J. Jack Stout. (1987). "Dispersion and habitat occupancy of the beach mouse, Peromyscus polionotus niveiventris." Journal of Mammalogy. 68(2): 297–304.

Gore, J.A. & T.L. Schaffer. (1993). "Distribution and conservation of the Santa Rosa beach mouse." Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Southeast Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. 47: 378–385.

Humphrey, S.R. (1992). Beach Mice. Pp. 76-91. In Rare and Endangered Biota of Florida. Vol. I Mammals. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Moyers, J.E. (1996). Food habits of Gulf Coast subspecies of beach mice (Peromyscus polionotus spp.). [Master’s thesis]. 83pp. Auburn University.

Oli, M., N.R. Holler, & M.C. Wooten. (2000). "Viability analysis of endangered Gulf Coast beach mouse (Peromyscus polionotus) populations." Biological Conservation. 97 (1): 1–12.

Stoddard, M. A., D.L. Miller, M. Thetford, & L. C. Branch. (2018). If you build it, will they come? Use of restored dunes by beach mice. Restoration Ecology. 77(3):531-537.

Swilling, W.R., M.C. Wooten, N.R. Holler, & W.J. Lynn. (1998). "Population dynamics of Alabama beach mice (Peromyscus polionotus ammobates) following Hurricane Opal." American Midland Naturalist. 140: 287–298.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (2000). Gulf Coast Beach Mouse Workshop Manual.

Wood, D.A. (2001). Beach Mice. Pp. 87–98. In Florida's Fragile Wildlife: Conservation and Management. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.