Scientific Name: Citrus latifolia Miller (syn. C. aurantifolia Christm. and C. x 'Tahiti')

Common Names: 'Tahiti' lime, 'Persian' lime, 'Bearss' lime, limon (Spanish), limão (Portuguese), limone (Italian).

Family: Rutaceae

Origin and History: The origin of 'Tahiti' lime is somewhat uncertain. Recent genetic analysis of citrus suggests the origin of this lime is southeast Asia, specifically east and northeastern India, north Burma (Myanmar), southwest China, and eastward through the Malay Archipelago (Moore 2001). Like Key lime, 'Tahiti' lime is probably a tri-hybrid intergeneric cross (a three-way hybrid involving three plant species and at least two different genera) of citron (Citrus medica), pummelo (Citrus grandis), and a microcitrus species, Citrus micrantha (Moore 2001). However, unlike Key lime, 'Tahiti' lime is a triploid. 'Tahiti' lime was first recognized in the United States in 1875, when a lime tree producing seedless fruit was discovered growing in a home landscape in California. The 'Tahiti' lime is thought to have arisen from a seed of citrus fruit imported to the United States from 'Tahiti' sometime between 1850 and 1880 (Ziegler and Wolfe 1961). By 1883 'Tahiti' lime was growing in Florida under the name 'Persian' lime, and by 1887 the 'Tahiti' lime was commercially produced in south-central Florida (sometimes called Lake Country). However, since the 1930s, the major 'Tahiti' lime production area was Miami-Dade County with secondary production along the south end of the Ridge (Polk and Highlands Counties) and Lee and Collier counties. Today, 'Tahiti' lime is grown on a very small commercial scale in Florida.

Distribution: 'Tahiti' limes are grown throughout warm subtropical and tropical areas of the world. Mexico is the largest commercial producer of the 'Tahiti' lime. Other countries where 'Tahiti' lime is grown commercially include Cuba, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Egypt, Israel, and Brazil.

Importance: Although the climate in South Florida is ideal for 'Tahiti' lime production, commercial production of the 'Tahiti' lime ended in Florida in the early 2000s due to the citrus canker eradication program. Today, the major 'Tahiti' lime producers, in order of importance, are Mexico, Brazil, Israel, and Australia (Roy et al. 1996). However, commercial production occurs throughout Central America, the Caribbean, and in Surinam and Venezuela. California has a small commercial 'Tahiti' lime industry (less than 1,000 acres).

Invasive potential: 'Tahiti' lime (Citrus latifolia) has not yet been assessed by the IFAS Invasive Plant Working Group on Non-Native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas and is not a considered a problem species at this time and may be recommended by IFAS faculty for planting.

Caution: Two diseases may limit or eliminate the potential for successful 'Tahiti' lime growing in the home landscape. Citrus canker—caused by Xanthomonas campestris pv. Citri—infects leaves, causing defoliation and reducing tree vigor and production (Spann et al. 2008a). Citrus greening (Huanglongbing/yellow shoot disease), caused by the bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter spp. and transmitted by the citrus psyllid (Diaphorina citri), infects the conducting tissues of trees, causing sections of the tree to die, as well as causing general tree decline, loss of fruit production, and tree death (Spann et al. 2008b). However, 'Tahiti' lime trees have been successfully grown in the home landscape if attention to fertilization is made and frequent small amounts of minor elements are applied to the foliage.

Description

Tree

The 'Tahiti' lime is small tree, reaching a height and spread of about 20 feet (5 m) with a rounded, dense canopy hanging to the ground.

Leaves

The leaves of the 'Tahiti' lime are dark green; oval to broadly lanceolate-shaped; 3.5–5 inches (9–13 cm) long by 1.8–2.5 inches wide; and persist up to three years on the tree. The wing on the petiole is usually narrow, but varies.

Inflorescence

Flowers have five white petals, about 1 inch (2.5 cm) in diameter, with many stamens that contain no viable pollen (Campbell 1984). The superior pistil is about 0.5 inch-long with a green ovary and yellow stigma and style. The flowers may be borne in clusters of five to 10 on new shoots, at the end of shoots or laterally adjacent to leaves. Some bloom occurs all year, with the heaviest bloom in Florida occurring from February to April.

Fruit

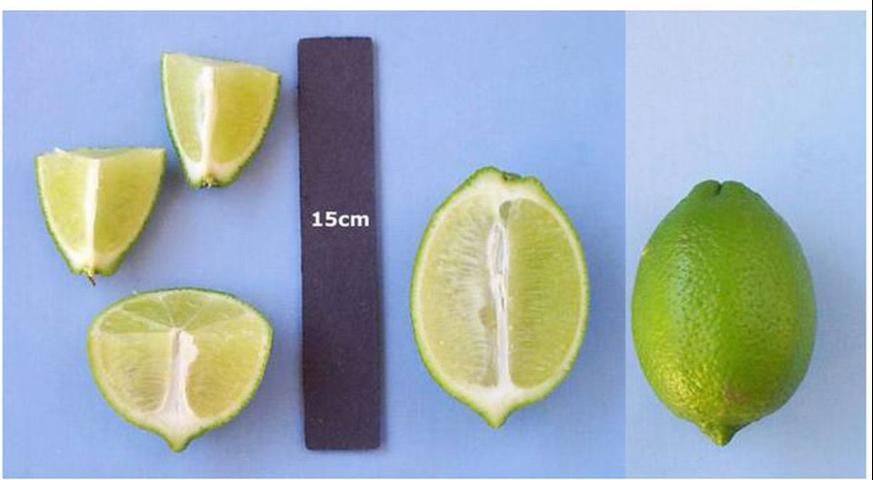

'Tahiti' limes are oval, 2 ¼–2 ¾ inches (5.5–7 cm) in length, 1 7/8–2 ½ inches (4.7–6.3 cm) in diameter, and weigh about 1.9 oz (54 g). The fruit have 10–12 segments (locules) and are medium to dark green at maturity, becoming yellow before dropping from the tree. When 'Tahiti' lime is grown in solid plantings, the fruit is seedless, but may produce a few seeds when planted along with other citrus species. Acids are 5–6 percent, soluble solids 8–10 percent, and juice content 45–55 percent by volume. The flavor and aroma are very good. The fruit requires 90–120 days from bloom to maturity, depending upon ambient temperatures. 'Tahiti' lime trees bear all year, with the greatest production in Florida occurring in June, July, and August.

Pollination

'Tahiti' lime does not require pollination to set fruit although honey bees and other insects frequently visit the open flowers.

Varieties

There are several clonal selections of 'Tahiti' lime, but they are generally similar enough in tree and fruit characteristics not to be important.

Climatic Adaptation

'Tahiti' lime has more cold hardiness than 'West Indian' lime (also called Mexican lime and Key lime) and pummelo (Citrus grandis), but less than grapefruit (Citrus paradise). In general, damage to 'Tahiti' lime leaves occurs at temperatures below 28°F (-2°C); wood damage occurs below about 26°F (-3°C), and severe damage or death occurs below 24°F (-4°C). 'Tahiti' lime trees grow best in the warmest areas of Florida.

Propagation

Only registered, disease-free trees should be purchased from a reputable nursery. 'Tahiti' lime trees may be propagated by budding (T-budding is common), grafting (e.g., veneer and cleft-grating), or air-layering (marcottage).

Air-layers (Marcotted Trees)

Air layered (marcottage) trees are propagated by inducing root formation on limbs that have a small-to-medium diameter. Air-layered trees come into bearing quickly, are moderately tolerant of wet or flooded soil conditions (Schaffer and Moon 1990), but are more susceptible to wind damage than are grafted or budded 'Tahiti' lime trees (Crane et al. 1993).

Selection of Planting Rootstock

Selection of a tree propagated on the appropriate rootstock is critical to satisfactory growth and production in the home landscape. Select the appropriate rootstock for the soil type in your landscape. Several selections or clones free of important diseases are available to nurserymen through the Florida Department of Agriculture Citrus Budwood Program (See https://www.fdacs.gov/Agriculture-Industry/Pests-and-Diseases/Plant-Pests-and-Diseases/Citrus-Health-Response-Program/Citrus-Budwood-Program). These trees are sold in nurseries as registered trees; we highly recommend them over any other type for growing a 'Tahiti' lime tree in the home landscape. 'Tahiti' limes may also be propagated by air-layering (marcottage). Air-layered trees do satisfactorily in high-pH, calcareous soils.

Appropriate rootstocks for grafted trees to be grown in high-pH, calcareous soils (rockland and some sandy soils) include the following: Rough lemon (Citrus jambhuri), Alemow (C. macrophylla), Rangpur lime (C. limonia), Volkamer lemon (C. volkameriana) (Campbell 1991), and several new hybrids (e.g., US-801, US-812, and US-897), as well as several new USDA somatic hybrids (Castle et al. 2004). A rootstock appropriate for low-pH or neutral soils is Swingle citrumelo (C. paradise 'Duncan' x Poncirus trifoliate). Air-layered and trees grafted onto Alemow tolerate a few days of excessively wet or flooded soil conditions (Schaffer and Moon 1990).

Fruit Production

'Tahiti' lime yields increase with tree age and size. Young, vigorous trees may produce 8–10 lbs their first year after planting and 10–20 lbs their second year (Crane, unpublished data). Well maintained trees may produce 20–30 lbs in year three after planting, 60–90 lbs in year four, 130–180 lbs in year five, and 200–250 lbs in year six (Campbell 1984). Non-pruned, large trees 12–15 years old may produce up to 700 lbs, however, 450–550 lbs is more common. Trees not fertilized and watered periodically may produce substantially less fruit than figures reported in this publication.

Placement in the Landscape

Planting distances depend on soil type and fertility and gardening expertise of the homeowner. 'Tahiti' lime trees in the home landscape should be planted in full sun, 15–20 feet or more (4.1–6.1 m) away from buildings and other trees. Trees planted too close to other trees or structures may not grow normally or may not produce much fruit due to shading.

Soils

'Tahiti' lime trees can be grown successfully in a variety of soils. However, well drained soils are essential for good fruit production and growth. Trees growing in high-pH, calcareous soils may be more susceptible to minor element deficiencies.

Planting a 'Tahiti' Lime Tree

Properly planting a 'Tahiti' lime tree is one of the most important steps in successfully establishing and growing a strong, productive tree. The first step is to choose a healthy nursery tree. Purchase only trees that are certified to be disease free and propagated under the rules and regulations of the Florida Budwood Certification Program. Commonly, nursery 'Tahiti' lime trees are grown in 3-gallon containers, and trees stand 2–4 feet from the soil media.

Large trees in smaller containers should be avoided as the root system may be "root bound." When a plant is root bound, all the available space in the container has been filled with roots to the point that the tap root or major roots are growing along the edge of the container in a circular fashion. Root-bound trees may not grow properly once planted in the ground.

Inspect the tree for insect pests and diseases and inspect the trunk of the tree for wounds and constrictions. Select a healthy tree and water it regularly in preparation for planting in the ground. The preferred time to plant is early spring, although potted trees may be planted any time in warm locations.

Site Selection

In general, 'Tahiti' lime trees should be planted in full sun for best growth and fruit production. Select a part of the landscape away from other trees, buildings and other structures, and power lines. Select the warmest area of the landscape that does not flood (or remain wet) after typical summer rainfall events.

Planting in Sandy Soil

Many areas in Florida have sandy soils. In such conditions, remove a 3–10 feet diameter ring of grass sod. Dig a hole three to four times the diameter and three times as deep as the container the 'Tahiti' lime came in. Making a large hole and loosen the soil adjacent to the new tree, so the roots of the tree can easily expand into the adjacent soil.

It is not necessary to apply fertilizer, topsoil, or compost in the hole. However, if you wish to add topsoil or compost to the native soil, mix the additional material in a ratio of no more than a 1:1 ratio with the soil excavated from making the hole.

Backfill the hole with some of the native soil removed to make the hole. Remove the tree from the container and place the tree in the hole so that the top of the soil media in the container is level with or slightly above the surrounding soil level. Fill soil in around the tree roots and tamp slightly to remove air pockets. Immediately water the soil around the tree and tree roots. Staking the tree with a wooden or bamboo stake is optional. However, do not use wire or nylon rope to tie the tree to the stake as these may eventually girdle and damage the tree trunk as it grows. Use a string made of cotton or another natural fiber, which will degrade slowly.

Planting in Rockland Soil

Many areas in Miami-Dade County have a very shallow soil with hard, calcareous bedrock several inches below the soil surface. Remove a 3–10 feet diameter ring of grass sod. Make a hole three to four times the diameter and three times as deep as the container the 'Tahiti' lime came in. To dig a hole in such soil, options include using a pick and digging bar to break the rock, or contract with a company that has augering equipment or a backhoe. Plant the tree as described for sandy soils.

Planting on a Mound

Many areas in Florida are within 7 feet or so of the water table and experience occasional flooding after heavy rainfall events. To improve plant survival, consider planting fruit trees on a mound of native soil 2–3 feet high by 4–10 feet in diameter. After the mound is made, dig a hole three to four times the diameter and three times as deep as the container the lime tree came in. In areas where the bedrock nearly comes to the surface (rockland soil), follow the recommendations for the previous section. In areas with sandy soil, follow the recommendations from the section on planting in sandy soil.

To promote growth and regular fruiting, lime trees should be periodically fertilized and watered, and insects, diseases, and weeds should be controlled on an as-needed basis.

Care of 'Tahiti' Lime Trees in the Home Landscape

A calendar for 'Tahiti' lime production in the home landscape is provided to outline the suggested month-to-month cultural practices.

Fertilization

In Florida, young 'Tahiti' lime trees should be fertilized every two to three months during the first year, beginning with 1/4 lb (114 g) of fertilizer and increasing to 1 lb (455 g) per tree (Table 1). Thereafter, three or four applications per year in amounts proportionate to the increasing size of the tree are sufficient, but not to exceed 12 lbs per tree per year.

Fertilizer mixtures containing 6–10 percent nitrogen, 6–10 percent available phosphorus pentoxide, 6–10 percent potash, and 4–6 percent magnesium give satisfactory results with young trees. For bearing trees, potash should be increased to 9–15 percent and available phosphoric acid reduced to 2–4 percent.

Examples of commonly available fertilizer mixes include 6-6-6-2 [6 (N)-6 (P2O5)-6 (K2O)-2 (Mg)] and 8-3-9-2 [8 (N)-3 (P2O5)-6 (K2O)-3 (Mg)]. Slow-release fertilizers containing these elements (and minor elements) are available and although expensive, reduce the frequency of fertilizer applications and reduce the potential for leaching of nutrients beyond the root zone.

From spring through summer, trees should receive three to four annual nutritional sprays of copper, zinc, manganese, and boron for the first four to five years. 'Tahiti' lime trees are susceptible to iron deficiency under alkaline and high-pH soil conditions. Iron deficiency can be prevented or corrected by periodic soil applications of iron chelates formulated for alkaline and high-pH soil conditions. These applications should occur during the late spring and the summer.

Irrigation

Newly planted 'Tahiti' lime trees should be watered at planting and then every other day for the first week or so and then once or twice a week for the first couple of months. During prolonged dry periods (e.g., five or more days of little to no rainfall), newly planted and young lime trees (first three years) should be well watered twice a week. Once the rainy season arrives, irrigation frequency may be reduced or stopped.

Once 'Tahiti' lime trees are four or more years old, irrigation will be beneficial to plant growth and crop yields during prolonged dry periods. Specific water requirements for mature trees have not been determined. However, as with other tree crops, the period from bloom through fruit development is important. Drought stress should be avoided at this time with periodic watering.

Prevention and Control of Insect Pests

Asian Citrus Psyllid (Diaphorina citri)

The Asian citrus psyllid attacks the leaves and young stems, severely weakening the tree (Mead 2007; Spann et al. 2008). The adult psyllid is 3–4 mm long with a brown mottled body and light-brown head. The nymphs (young) are smaller and yellowish orange. A white, waxy excretion (ribbon-like shape) is characteristic for this psyllid. Foliage attacked by this psyllid is severely distorted. Despite treatments available to control the psyllid, preventing infestation in a home landscape is difficult at best because of the presence of alternative hosts (e.g., orange jasmine) and the lack of control in neighboring properties.

This psyllid transmits the gram-negative bacterial disease called Huanglongbing/yellow shoot disease, which is deadly to citrus trees (Yates et al. 2008). (See below for more information on citrus greening.) Please contact your local Agricultural Extension Agent for current recommendations.

Brown Citrus Aphid (Toxoptera citricida)

Adult, wingless forms are shiny black, and nymphs (young) are dark-reddish-brown (Halbert and Brown 2008). This aphid may be confused with several other dark-colored aphids. Both wingless and winged forms of the brown citrus aphid feed on new growth, causing distortion. When populations of this aphid are very high, stem dieback may occur.

The brown citrus aphid is a major vector of citrus tristeza virus (CTV) and may cause tree decline and death of 'Tahiti' lime trees on susceptible rootstocks (e.g., sour orange, alemeow). Purchase and planting of certified disease-free citrus trees under the Florida Citrus Budwood Program will help reduce the spread or introduction of this disease into your landscape.

Citrus Leafminer (Phyllocnistis citrella)

The citrus leafminer adult moth is small (4 mm wingspan), with white and silvery-colored wings with several black and tan markings (Heppner 2003). The larvae of this moth usually infest the upper leaf surface, forming meandering mines. Their mining causes leaf distortion, which reduces the functional surface area of the leaf. The immature leaves of 'Tahiti' lime trees in the home landscape are commonly attacked by the citrus leafminer during the warmest time of the year and less so during the winter months (Browning et al. 1995). Citrus leafminer feeding may severely damage the leaves, which may weaken young, newly planted trees. Application of horticultural oil in a ½–1 percent solution to a new flush of leaves (when ½–1 inch in length) will usually protect the leaves sufficiently as they mature. Once trees are three years old or more, they can withstand the damage to the leaves by the citrus leafminer. In general, leaf flushes that develop during the cool temperatures of late fall and winter avoid attack by the citrus leafminer.

Mites

Several mites may attack 'Tahiti' lime leaves, stems, and fruit.

Citrus Red Mite (Panonychus citri)

The red mite usually attacks the upper leaf surface, resulting in brown, necrotic areas. Severe infestations may cause leaf drop (Browning et al. 1995; Jackson 1991). The red mite has a deep-red to purple color and round body. Red mite infestations are greatest during the dry winter months, but may occur from November to June (Childers and Fasulo 2005). Red mites are a problem during dry periods. When heavy infestation occurs, foliar applications of sulfur will control red mites. Caution: Never apply a sulfur spray and an oil spray within three weeks of each other.

Rust Mite (Phylocoptruta oleivora) and Broad Mite (Polyphagotarsonemus latus)

The rust mite and broad mite may attack leaves, fruit, and stems, but these mites are primarily a fruit pest (Fasulo 2007). Rust mites are very hard to see because of their small size (0.1 mm long) and light-yellow color (Jackson 1991). Broad mites are 0.2 mm in length, with color varying from light-yellow to dark-green (Fasulo 2007). Feeding by these mites results in russetting (browning) of the fruit peel, but, unless severe, does not affect internal fruit quality. When heavy infestation occurs, foliar applications of sulfur will control red mites. Caution: Never apply a sulfur spray and an oil spray within three weeks of each other.

Sulfur will control red mites. Caution: Never apply a sulfur spray and an oil spray within three weeks of each other.

Scale Insects

Various scale species may develop damaging infestations on bark, leaves or fruit.

Florida Red Scale (Chrysomphalus aonidum)

This armored scale is circular in shape (1.5–2.2 mm in diameter) with a prominent, central nipple and varies in color from reddish-brown to reddish-purple (Browning et al. 1995; Fasulo and Brooks 2004; Jackson 1991). Mostly a pest on leaves, this scale can also be found attacking fruit. Symptoms appear as leaf drop and reddish to reddish-brown stipling of the leaves, especially along the central main vein. Application of horticultural oil in a ½–1 percent solution to the leaves will usually control this pest.

Snow Scale (Uaspis citri)

The clustering of the white male scales along limbs and tree trunks looks like white flecking or snow (Browning et al. 1995; Fasulo and Brooks 2004). The female scales are brown to purple in color. The scale feeding causes the bark to split and weakens the tree; sometimes killing limbs. Several applications of horticultural oil in a ½–1 percent solution to the affected limbs and trunk will usually control this pest.

Diseases

Algal Disease (Red alga)

Caused by Cephaleuros virescens, red alga infects leaves and bark and can cause leaf drop and girdling of branches, which results in stem dieback. Control is by 1–2 copper-based sprays from midsummer to late summer.

Citrus Canker (Xanthomonas campestris pv. citri)

'Tahiti' lime trees are moderately susceptible to citrus canker (Spann et al. 2008). Citrus canker is caused by bacteria, which may be spread by wind-driven rain and contaminated equipment, clothing, animals, and humans. Young leaves, shoots, and fruit of the 'Tahiti' lime are susceptible to infection (Browning et al. 1995; Spann et al. 2008a). Pinpoint spots on leaves and fruit appear first, followed by raised, brown spots that are circular to irregular in shape and appear on leaves, stems, and fruit, surrounded by a yellow halo. Heavy infestations of citrus canker may result in defoliation and weakening of the tree.

Planting trees in full sun with good air movement and avoiding wetting the foliage during watering may help reduce the severity of this disease. Timely applications of copper-based fungicides to newly emerging leaves will also lessen the impact of this disease.

Citrus Greening (Huanglongbing/yellow dragon disease)

Citrus greening is caused by the bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter spp. (Spann et al. 2008b). The bacteria is spread by the Asian citrus psyllid (Diaphorina citri). Symptoms of citrus greening include sections of the tree showing severe symptoms similar to those resulting from nutrient deficiencies (e.g., yellow blotching, yellow veins, reduce leaf size), corky main veins; and stem and limb dieback. Frequent applications of foliarly applied minor element sprays to the tree will minimize the amount of stem and limb dieback that develops over time. However, trees where fertilizer is withheld will eventually have stem and limb dieback and the entire tree may decline and die. No curative treatment is available for the disease at this time.

Purchase and planting of citrus trees certified under the Florida Citrus Budwood Program will help reduce the spread or introduction of citrus greening onto your landscape. Removal of infected trees is also recommended as infected trees will act as a source of new infection to nearby citrus. In the future, citrus greening disease resistant or tolerant rootstocks may become available.

Citrus Scab (Elsinoe fawcetti)

Like greasy spot and melanose, this disease is most prevalent during the rainy season. Young leaves, stems, and fruit are most susceptible to infection. The major symptom is development of corky outgrowths in infected tissues (Browning et al. 1995). Citrus scab is usually not a major disease on limes and is usually controlled by the same foliar treatments for greasy spot and melanose.

Foot Rot (Phytophthora parasitica)

Resistance to foot rot varies by rootstock. Trifoliate orange is immune. Swingle citrumelo, Cleopatra mandarin, and sour orange are resistant. Troyer and Carrizo citranges and Rangur lime are tolerant. Sweet orange and rough lemon are highly susceptible (Browning et al. 1995). Symptoms of foot rot include bark peeling in the crown roots and trunk at the soil level, gumming at the wounded area, leaf chlorosis, stem dieback, tree decline, and death. The best way to avoid this disease is to grow 'Tahiti' lime on resistant rootstocks, avoid trunk damage, avoid wetting the trunk when watering, and keep mulch away from the base of the tree trunk.

Greasy Spot (Mycosphaerella citri)

On trees affected with this leaf disease, yellow spots initially appear on the upper leaf surface. Brown, irregularly shaped blisters with a greasy appearance then develop on the lower leaf surface (Browning et al. 1995). Eventually, brown blisters appear on the upper leaf surface. The disease may lead to defoliation, which weakens the tree. Greasy spot is prevalent during the rainy season (May to September) and easily prevented and controlled with one or two copper or copper-plus horticultural oil sprays.

Melanose (Diaporthe citri)

Immature leaves, stems, and young fruit are most susceptible to melanose (Browning et al. 1995). Early leaf symptoms appear as small, brown, sunken spots, which later become raised and have a sandpaper-rough feel. Fruit symptoms appear as raised, irregularly shaped brown spots, surrounded by white/off-white halos, due to cracking of the peel. Like greasy spot, this disease is most prevalent during the rainy season. Melanose is usually not a major disease on limes and is typically controlled by the same foliar treatments that are effective for control of greasy spot.

Postbloom Fruit Drop (Colletotrichum acutatum)

Occurrence of this disease is most prevalent during the rainy season; overhead watering may also increase the incidence of this disease in the home landscape. The initial symptoms of this disease include brown-to-orange, water-soaked lesions on the flower petals. This symptom is followed by the petals turning orange and desiccating (Browning et al. 1995). The pistal and young fruitlets drop off, leaving the floral disk and calyx (button), which may remain attached to the stem for a number of years.

Strategies to minimize the incidence of this disease include planting the tree in full sun in an area of the landscape with good air movement, periodically pruning the canopy to facilitate penetration of sunlight and air, and not watering the tree foliage during bloom time. Do not apply copper to the foliage and flowers during bloom as this aggravates postbloom fruit drop.

Tristeza

'Tahiti' limes may be susceptible to severe tristeza virus strains, regardless of rootstock. However, these trees may be susceptible to less-severe strains when propagated on Citrus macrophylla (macrophylla) and rough lemon (C. jambhiri) rootstocks (J.H. Crane, personal communication). Tristeza is transmitted by the brown citrus aphid (Toxoptera citricida). Purchasing trees that are certified disease-free under the Florida Budwood Registration Program will greatly reduce the chances of obtaining a tree that is infected with this disease.

Physiological Disorders

Lime Blotch Disease

Not caused by an organism, lime blotch disease is a genetic disorder. Symptoms include chlorotic blotching of leaves, chlorotic sectoring of skin of fruit, dieback of branches, formation of gummy lesions on branches and trunk, and eventually death of the tree. This disorder may be avoided by planting only certified trees propagated under Florida Citrus Budwood Program.

Oleocellosis (Oil spotting)

This disorder is caused by rupturing of the oil glands in the peel; the released oil is toxic to the surface cells (Mustard 1954). Peel symptoms appear as irregularly shaped sunken areas that are discolored light-brown to brown. This disorder occurs when fruit are fully turgid and may be avoided by gentle handling during harvest and waiting until afternoon to harvest.

Stylar-end Breakdown (Stylar-end Rot)

This disorder appears as a breakdown of tissues at the stylar end of fruit, eventually causing decay of entire fruit (Browning et al. 1995; Davenport et al. 1976). The disorder usually occurs when fruit are fully turgid (full of water) in the morning, during hot weather, July through September. Stylar-end breakdown is caused by rupture of the juice sacs when the fruit is harvested and handled roughly. Large, mature fruit are most susceptible. The incidence of stylar-end breakdown may be decreased by handling fruit gently when harvesting and by waiting until afternoon to harvest.

Nutritional Disorders

Nitrogen Deficiency

This condition first appears on the older leaves. However, with prolonged deficiency, younger leaves are also affected (Zekri and Obreza 2003a; Futch and Tucker 2008). In the case of a mild nitrogen deficiency, the foliage will be light green. As the deficiency intensifies, the light green turns to yellow. Nitrogen-deficient trees may be stunted, with a sparse canopy and limited fruit production.

Phosphorus Deficiency

Like nitrogen deficiency, phosphorus deficiency appears first in older leaves; more severe deficiency also appears in young leaves (Zekri and Obreza 2003a; Futch and Tucker 2008). Symptoms begin with a loss of deep-green color. New leaves are small and narrow and may have a purplish or bronze discoloration. Fruit from phosphorus-deficient trees have a coarse, rough, thick rind and a hollow core.

Potassium Deficiency

Potassium deficiency first appears on older leaves as a yellowing of the leaf margins and tips; subsequently the yellow areas broaden (Zekri and Obreza 2003a; Futch and Tucker 2008). If potassium deficiency persists and becomes severe, leaf spotting and dead areas may develop.

Magnesium Deficiency

The first symptom of magnesium deficiency appears on mature foliage as a yellowish-green blotch near the base of the leaf and between the midrib and the outer edge (Zekri and Obreza 2003b). The yellow area enlarges until the only green parts remaining are at the tip and base of the leaf as an inverted-V-shaped area on the midrib. With acute magnesium deficiency, the leaves may become entirely yellow and eventually drop.

Manganese Deficiency

This deficiency appears first on younger leaves as dark-green bands along the midrib and main veins, surrounded by light-green interveinal areas (Zekri and Obreza 2003b). As the severity of the deficiency increases, the light-green interveinal areas develop a bronze appearance.

Zinc Deficiency

First symptoms of zinc deficiency occur in young leaves. In the early stages, this deficiency appears as small blotches of yellowing occurring between green-colored veins in the leaf (Zekri and Obreza, 2003b). Leaves that are severely deficient in zinc may become entirely yellow except for the green, veinal areas, and leaves will be smaller and have narrow, pointed tips. This deficiency has been referred to as "little leaf" and "mottle leaf." The distance between leaves (internodes) becomes reduced, giving the shoot a rosette appearance.

Iron Deficiency

Iron deficiency symptoms first appear in young leaves with the leaf veins a darker green than the interveinal areas (Zekri and Obreza 2003b). If this deficiency persists, the yellow in the interveinal areas expand with the entire leaf areas eventually becoming yellow. Leaf size is also reduced. Trees may become partially defoliated.

'Tahiti' Lime Trees and Lawn Care

'Tahiti' lime trees in the home landscape are susceptible to trunk injury caused by lawn mowers and weed whackers. Maintain a grass-free area 2–5 feet or more from the trunk of the tree. Never hit the tree trunk with lawn-mowing equipment and never use a weed whacker near the tree trunk. Mechanical damage to the trunk of the tree will result in weakening of the tree and, if severe, can cause the tree to dieback or die.

Roots of mature 'Tahiti' lime trees spread beyond the drip-line of the tree canopy. Heavy fertilization of the lawn adjacent to 'Tahiti' lime tree is not recommended and may reduce fruiting and or fruit quality. The use of lawn sprinkler systems on a timer may result in over watering, which can cause 'Tahiti' lime trees to decline as a result of root rot caused by too much water applied too often.

Mulch

Mulching 'Tahiti' lime trees in the home landscape helps retain soil moisture, reduces weed problems under the tree canopy, and improves the soil near the surface. Mulch 'Tahiti' lime trees with a 2–6 inch (5–15 cm) layer of bark, with wood chips, or with similar mulch material. Keep mulch 8–12 inches (20–30 cm) from the trunk. Mulch placed against the tree trunk may result in trunk rot.

Pruning

Generally, 'Tahiti' lime trees have a round canopy and need only limited pruning. Prune only to shape trees, to remove dead or diseased wood, to improve light and penetration of spray material, and to limit tree size. Keep the tree height in the range of 6–8 feet. Maintaining tree height in this range will reduce potential wind damage (e.g., uprooting) and help facilitate cultural practices such as spraying micronutrients onto the foliage. This tree height will also facilitate harvesting of the fruit.

Harvest, Ripening, and Storage

'Tahiti' limes should be harvested when they reach about 1¾ inches (45 mm) in diameter and are dark to medium-dark green (Figure 1). Fruit harvested before this size may have little to no juice. Fruit may be stored in a polyethylene bag in the refrigerator for about 10 days.

Use and Nutrition

'Tahiti' lime juice has no cholesterol and is a source of Vitamin A and Vitamin C (Table 2). Fresh fruit is used as garnish for meats and drinks. Fresh juice is used in beverages, as well as in marinating fish and meats and in seasoning many foods. Frozen and canned juice is used in similar ways. Oil of the Tahiti lime is widely used in flavorings and cosmetics.

Literature Cited

Browning, H.W., R.J. McGovern, L.K. Jackson, D.V. Calvert, and W.F. Wardowski. 1995. Florida citrus diagnostic guide. Fla. Science Source, Inc., Lake Alfred, Fla. P. 1–244l

Campbell, C.W. 1984. 'Tahiti' lime production in Florida. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00028121/00001/

Campbell, C.W. 1991. "Rootstocks for the 'Tahiti' lime." Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 104:28–30.

Castle, W.S., J.W. Grosser, F.G. Gmitter, Jr., R.J. Schnell, T. Ayala-Silva, J.H. Crane, and K.D. Boman. 2004. "Evaluation of new citrus rootstocks for 'Tahiti' lime production in south Florida." Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 117:174–181.

Childers, C.C. and T.R. Fasulo. 2005. Citrus red mite. ENY817. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://original-ufdc.uflib.ufl.edu/IR00004619/00001.

Crane, J.H., R.J. Campbell, and C.F. Balerdi. 1993. "Effect of Hurricane Andrew on tropical fruit trees." Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 106:139–144.

Davenport, T.L., C.W. Campbell, and P.G. Orth. 1976. "Stylar-end breakdown in 'Tahiti' lime: some causes and cures." Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 89:245-248.

Jackson, L. 1991. Citrus growing in Florida (3rd edition). Univ. of Fla. Press, Gainesville, Fl.193–197.

Fasulo, T.R. 2007. Broad mite (Polyphagotarsonemus latus (Banks) (Arachnida: Acari: Tarsonemidae). EENY183. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN340.

Fasulo, T.R. and R.F. Brooks. 2004. Scale pests of Florida citrus. ENY814. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/CH059.

Futch, S.H., and D.P.H. Tucker. 2008. A guide to citrus nutritional deficiency and toxicity identification. HS797. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/CH142.

Halbert, S.E. and L.G. Brown. 2008. Brown citrus aphid, Toxoptera citricida (Kirkaldy). EENY007. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN133.

Heppner, J.B. 2007. Citrus leafminer, Phyllocnistis citrella Stainton (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Phyllocnistinae). EENY038. Gainesville:University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN165.

Mead, F.W. 2007. Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Insecta: Hemiptera: Psyllidae). EENY033. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN160.

Moore, G.A. 2001. "Oranges and lemons: clues to the taxonomy of Citrus from molecular markers." Trends in Genetics 17: 536–540.

Mustard, M.J. 1954. "Oleocellosis or rind-oil spot on Persian limes". Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 67:224–226.

Roy, M., C.O. Andrew and T.H. Spreen. 1996. Persian limes in North America. Fla. Sci. Source, Inc., Lake Alfred, Fla. P. 1–132.

Schaffer, B. 1991. "Flood Tolerance of 'Tahiti' Lime Rootstocks in South Florida Soil." Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 104:31–32.

Schaffer, B. and P.A. Moon. 1990. "Influence of rootstock on flood tolerance of 'Tahiti' lime trees". Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 103:318–321.

Spann, T.M., R.A. Atwood, J.D. Yates, and J.H. Graham, Jr. 2008a. Dooryard citrus production: citrus canker disease. HS1130. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00002662/00001/.

Spann, T.M., R.A. Atwood, J.D. Yates, M.E. Rogers, and R.H. Brlansky. 2008b. Dooryard citrus production: citrus greening disease. HS1131. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00002663/00001/.

Yates, J.D., T.M. Spann, M.E. Rogers, and M.M. Dewdney. 2008. Citrus greening: a serious threat to the Florida citrus industry. CH198. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/CH198.

Zekri, M. and T.A. Obreza. 2003a. Macronutrient deficiencies in citrus: nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. SL 201. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/SS420.

Zekri, M. and T.A. Obreza. 2003b. Micronutrient deficiencies in citrus: iron, zinc, and manganese. SL 204. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/SS423.

Ziegler, L.W. and H.S. Wolfe. 1961. Citrus growing in Florida. Univ. of Fla. Press, Gainesville, Fl. P. 51–53.

Cultural calendar for 'Tahiti Lime' production of mature (bearing) trees in the home landscape.