Florida has thousands of natural and man-made ponds which range in surface area from less than 1/10 acre to greater than ten acres. Man-made ponds include dug-out and impounded waters, limerock pits, and sand or gravel pits, commonly called borrow pits. Fishing pressure on public waters is increasing due to Florida's rapidly growing population and the growing interest in fishing as a source of recreation and food. Competition for public fishery resources, coupled with the high cost of transportation to go fishing, has resulted in an increased interest in fishing private waters that are closer to home. These private ponds must, therefore, be more intensively managed to maintain good quality fishing for the pond owner's personal recreation or as a source of income.

Ponds that consistently produce good catches of fish require the proper stocking of the correct species and number of fish, a balanced harvest of mature fish, good water quality, and proper aquatic vegetation management. Many unmanaged ponds can produce more pounds of fish if good management practices are followed. The annual harvest of fish can provide hours of recreation, an excellent source of food, and even a supplemental income. The purpose of this publication is to provide an introduction to the management of Florida ponds for fishing.

Stocking the Pond

What to Stock

Largemouth bass, bluegill (commonly called sunfish or bream), and channel catfish are the most commonly stocked species in Florida ponds. When properly managed, these species can provide excellent fishing.

Largemouth Bass and Bluegill

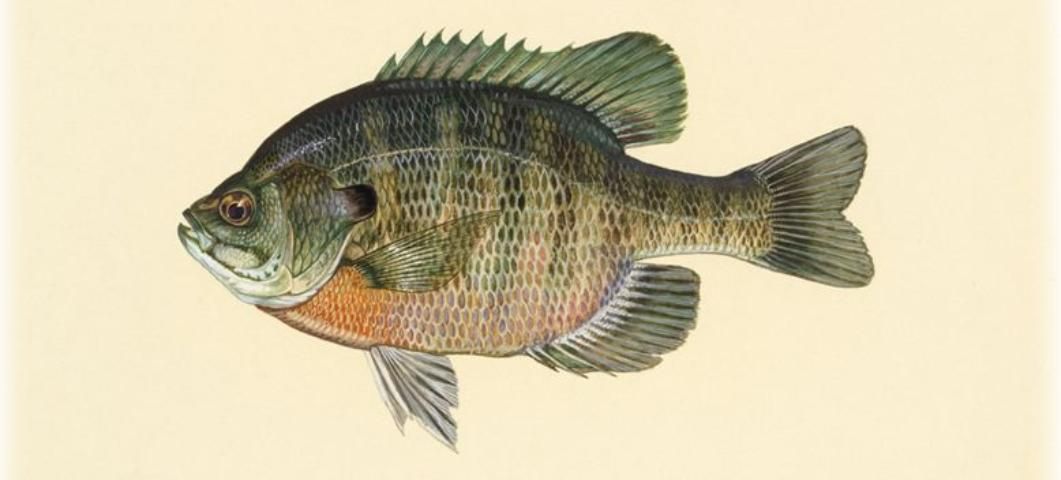

The largemouth bass (Figure 1) is a predatory species and requires large numbers of small fish as prey to maintain good growth. Many pond owners are reluctant to stock bluegill (Figure 2) into their ponds because of their tendency to overpopulate and stunt, however, when stocked in conjunction with bass and properly fished, this species provides food for the bass and a fine sport fish for the angler. Without bluegill or other suitable prey species, a quality bass fishery will not develop.

Credit: Duane Raver Jr.

Credit: Duane Raver Jr.

Channel Catfish

The channel catfish (Figure 3) is both a popular food and sport fish in Florida. This species should be stocked alone in ponds smaller than one-half acre or in ponds that are muddy throughout the year. In larger ponds, catfish do well when stocked alone or with bass and bluegill. If stocked alone, catfish may overpopulate if spawning sites are available, so the addition of milk cans and sewer tiles to provide spawning sites is discouraged. In the presence of bass, the survival of small catfish is lowered because of predation. Supplemental stocking with catfish in the 8-to-l0 inch size range is required to maintain their population in ponds with bass.

Credit: Duane Raver Jr.

Redear Sunfish

The redear sunfish (Figure 4), commonly called the shellcracker, can also be stocked as a prey species for bass and as a sport fish for the angler. This species should not be stocked alone or comprise more than 30% of the initial stocking of sunfish (bluegill and redear sunfish) because it will not produce enough offspring to sustain the bass population. When stocked with bluegill, these two species will often produce hybrids which grow faster and to a larger size than either of the parents.

Credit: Duane Raver Jr.

White Amur

The white amur, commonly called the grass carp (Figure 5), can be stocked into a pond to control aquatic vegetation. A permit must first be obtained from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission before this species can be introduced into a pond in Florida. Only triploid grass carp, which are sterile, are legal for use in Florida ponds.

Credit: Artwork courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department ©2004

What Not to Stock

Many other species have been stocked into ponds, but none have been as successful as the largemouth bass, bluegill, and channel catfish combination. While other species do well in streams, lakes or reservoirs, they often cause problems in ponds or are not well suited for the pond environment.

Crappie

Black crappie (Figure 6) and white crappie, also known as specks, speckled perch or white perch, are among the worst fish to stock into ponds. They compete with bass for food, eat small bass, and have a tendency to overpopulate and become stunted in a pond. They spawn prior to bass in the spring. The young crappie quickly grow too large to serve as prey for young bass.

Credit: Duane Raver Jr.

Common Carp and Bullheads

Common carp and bullheads (Figure 7) should be avoided because they will stir up the pond bottom while feeding, causing muddy water. Bullheads will also often overpopulate in a pond.

Credit: Duane Raver Jr.

What Sizes to Stock

New or reclaimed ponds are normally stocked with small (1- to 4-inch) fish, called fingerlings. These small fish will produce harvestable populations in one to two years. Care must be taken to make sure that wild fish are not present in the pond, or the newly stocked small fish may be eaten.

To shorten the time before a pond becomes fishable, larger fish can be stocked. These will be more expensive to stock, but the amount of time required before fish can be harvested from the pond can be reduced.

How Many to Stock

It is critical that the correct number of each species of fish is stocked. Improper stocking rates may prevent a pond from producing a quality fishery. In Florida, 100 bass and 500 bluegill fingerlings are normally stocked per acre. Catfish can be stocked at 100 per acre, along with the bass and bluegill or by themselves in catfish-only ponds. If the catfish are to be fed, then higher stocking rates of catfish can be used. If larger fish are stocked, fewer fish are required. Stocking rates of fifty 8- to 12-inch bass, two hundred 4- to 5-inch bluegill and fifty to one hundred 8- to 12-inch catfish should be used.

When and How to Stock

To prevent wild fish from becoming established and competing with stocked fish, a pond should be stocked as soon after it is filled or reclaimed as possible. Bluegill and catfish are normally stocked in the fall, and bass are stocked the following spring. Stocking bluegill in the fall will allow them to spawn, providing the small bass with a forage base. Catfish are stocked in the fall to allow them to grow large enough so that the bass will not be able to eat them. Bass are stocked in the spring because they are highly cannibalistic, and if left in the hatchery ponds in large numbers throughout the summer, they would eat each other, thereby reducing the number of fingerlings that would be available for stocking. Contact your regional Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission office or your County Extension Service office for a list of local fish suppliers.

Stocking a pond in mid-summer should be avoided. High water temperatures and low dissolved oxygen may weaken fish being transported. Sudden temperature changes can cause fish to go into shock and die. When stocking fish, transport water and pond water temperatures should be equalized by slowly adding pond water into the transport container. The fish can then be added to the pond when the water temperature in the container is about the same as that of the pond.

Fish Management

Fishing the Pond

When it comes to managing a pond for fishing, a distinction must be made between fishing and harvesting. Fishing is simply the act of trying to catch or catching fish, while harvesting is removing the fish from a pond. Generally, no limit needs to be placed upon the fishing of a pond, but fish harvest must be closely controlled. Occasionally, a fish that is returned to the pond may die from hook injuries or mishandling. These fish must be considered as part of the harvest. If properly handled, few fish will die while being caught and released.

Overharvesting of bass probably ruins fishing in more Florida ponds than any other cause. Anglers can easily overharvest the bass population during the first season of fishing. This allows the bream (bluegill and redear sunfish) to overpopulate the pond. The likelihood of bass overharvest can be reduced if the pond owner restricts the harvest of bass by anglers. However, making a pond off limits to everyone is not encouraged because underharvesting can also lead to problems.

The most sensible way to prevent bass overharvest is to establish a 15-inch length limit for a period of two to three years following stocking. If during this time, all bass that are less than 15 inches in length are released, the pond should begin producing harvestable-sized fish of all species. During this time, the fish that were originally stocked will have to support most of the fishing, so care must be taken not to overharvest these fish.

Two to three years after stocking, a decision should be made as to what size fish are desired. Bass will have reproduced two or three times during this period, yielding an abundance of small young bass. If left unharvested, these young bass will grow slowly due to competition with each other, resulting in a bass population comprised primarily of fish less than 12 inches in length. These small bass will feed heavily upon the sunfish, controlling their number. Fewer sunfish will be available for harvest, but they will be of larger size (7 to 8 inches). The catch will thus consist of small bass and large sunfish.

If the pond owner is interested in harvesting bass larger than 15 inches in length and sunfish of a variety of sizes, then 12- to 15-inch bass should be released after the initial two to three years following stocking. Bass of this size grow rapidly, produce many young, and prey heavily upon intermediate-sized sunfish. About twenty-five 8- to 12-inch bass should be harvested per acre per year, along with any bass larger than 15 inches. Total bass harvest should not exceed 20 to 25 pounds per acre per year. A good rule of thumb is to also harvest 4 to 6 pounds of sunfish for every pound of bass harvested.

Catfish can be harvested at any rate desirable to the pond owner. A good record of catfish harvest should be kept, so that the catfish population can be maintained at a predetermined level by supplemental stocking of 8- to 12-inch fingerlings as needed. This size catfish fingerlings must be stocked to prevent them from being eaten by bass.

Stock Assessment and Correction

If the fish have not been properly harvested, an adjustment of the fish populations may be required. If primarily 3- to 5-inch bluegill and few or no bass are caught, then overharvest, high natural mortality, or poor survival of young bass has occurred. This problem can be corrected by stocking fifty 8- to 12-inch bass per acre. Bass less than 15 inches in length should be released when caught until small bass become abundant. One of the harvest strategies mentioned above can then be followed.

If only small bass and no sunfish are caught, harvest of bass has not been adequate or no sunfish are present. In this situation, 200 4- to 5-inch bluegill should be stocked per acre. Approximately twenty 8-to 12-inch bass should be harvested per acre per year over the next two years. After this time, a decision should be made as to which of the management strategies described above will be followed.

Removal of Unwanted Fish

Ponds which contain large numbers of rough fish such as gar, bowfin (mudfish), bullheads, carp, suckers or shad are best managed by the complete removal of all fish from such ponds, and then restocking with desirable species. This process is called pond renovation.

The least expensive method of removing unwanted fish from a pond is to drain it and to allow its bottom to dry. Unwanted fish will often leave the pond through the standpipe. Those remaining will die as the pond water evaporates. This will effectively remove any fish from the pond, and will allow bottom sediments to oxidize. Many impounded ponds in the Florida panhandle can be drained. If a pond cannot be drained, as is the case with many dug-out ponds in Florida, any water remaining in the pond can be treated with chemicals to kill the fish. Rotenone is the chemical most frequently used. When used at recommended rates, rotenone is not harmful to livestock or other warm-blooded animals, even if they drink the pond water immediately after treatment. During the autumn, when water temperatures are above 70 F, is the best time to renovate a pond to ensure a complete kill prior to restocking.

Rotenone (a restricted-use pesticide) comes in both an emulsifiable powder and liquid form. The powdered form can often be obtained from your local feed and seed store. The liquid form is occasionally available from local sources, but is usually mail-ordered. Contact your County Extension office or the regional office of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to find sources. The first step in reclaiming a pond is to determine the quantity of rotenone required. The surface area of the pond (in acres) should be multiplied by the average depth of the pond (in feet) to give the pond volume in acrefeet. At the recommended rate of 2 parts per million, 5 pounds of 5% powder or 0.65 gallons of liquid rotenone is needed for each acre-foot of water. For example: if you have a 1-acre pond with an average depth of 5 feet and you treat with 0.65 gallons of rotenone per acre-foot, you will need 3.25 gallons of rotenone (1 acre X 5 feet X 0.65 gallons per acre-foot = 3.25 gallons).

The next step is preparing the rotenone for application. If the powdered form is used, water is first added to the powder to form a paste. Additional water is then added until the paste is evenly mixed with the water (about 10 gallons of water to 5 pounds of rotenone). Likewise, the liquid form is diluted with water (about 1 gallon of rotenone with 10 gallons of water).

Finally, the rotenone is applied to the pond. Uniform distribution of the rotenone-water mixture is necessary to assure the complete removal of all fish. Most areas can be treated by pouring the chemical into the prop wash of an outboard as you slowly motor around and across the pond. Rotenone can be applied to shallow marshy areas and the shoreline with a garden sprayer. Deep areas should be treated by either pumping the chemical below the surface or by gravity feeding the rotenone through a perforated hose that is weighted at one end while moving across the deep areas. The reintroduction of unwanted fish species can occur from small pockets of water located upstream from the treated pond. To prevent this from happening, these areas should also be treated.

Ponds should be stocked soon after reclamation, but not until the rotenone is detoxified, generally about 7 to 14 days after application. In cold water, rotenone may remain toxic for longer periods of time. Toxicity can be tested by placing several live fish into a cage placed in the pond, and then observing the fish for several days to make sure that none of them die.

Scaled fish can be selectively removed from catfish ponds without harming the catfish by using Antimycin-a according to label directions. This chemical is most effective at warm temperatures and in neutral or slightly acid ponds.

Feeding Your Fish

Fish can be fed artificial diets on an occasional basis to attract them to selected areas so that they can be more readily caught by anglers, or fed more intensively to promote rapid growth and higher standing crops (pounds per acre). Species such as the channel catfish and bluegill respond well to artficial feeds. Commercially produced pelleted catfish feed is an excellent choice (for further information, see Florida Cooperative Extension Service Fact sheet FA1, "Catfish Feeds and Feeding"). Floating pellets are preferred over sinking feeds because species such as the bluegill will better utilize the floating form, and the pond owner will be able to determine if all the feed is being eaten. In addition, the pond owner will be able to determine if the fish go off feed, which could be an indication that the fish are sick or water quality is poor.

If a pond is heavily fished, an intensive feeding program can be established. Begin by feeding at a rate of two pounds per surface acre per day. Feed at several locations around the pond. Feeding should be daily, at the same time, and at the same locations. Feeding rates can be increased as the fish learn to take the pellets, but do not exceed ten pounds of feed per surface acre per day, and do not feed the fish more than they can eat in 10 to 15 minutes. Also, do not feed them when the water temperature is below 60o F, or, above 95o F. Fish do not actively feed at these times. Excessive feeding can lead to the increased chance of fish kills due to low oxygen and can become costly.

Feeding small quantities of food or on an occasional basis will likely have limited benefits to increased fish growth and standing crops. Feeding fish can, however, be an enjoyable experience, and should help in attracting fish to established feeding locations so that they can be more readily caught. Feeding may indirectly increase the natural productivity of a pond by introducing small quantities of nutrients into the pond each time the fish are fed.

Fish Diseases, Parasites, and Kills

Fish are prone to diseases and parasites just like any other animal (see Florida Cooperative Extension Service Circular 716, "Introduction to Freshwater Fish Parasites"). Their diseases are caused by bacteria, fungi, or viruses. Fish are most susceptible to disease outbreaks in the spring as water temperatures are increasing and their resistance is at its lowest coming out of the winter, and in the summer when water temperatures are high and water quality is often poor (see UF/IFAS Extension Circular 715, "Management of Water Quality for Fish"). Generally, mortality is low in natural populations, such as in sportfish ponds, but can be a major problem when they are crowded as in aquaculture ponds. The cost of treating diseases is usually prohibitive in most private recreational ponds. The best rule of thumb is to let such disease outbreaks run their natural course.

Most fish have parasites, such as crustaceans, flukes, leeches, protozoans, roundworms, and tape-worms. Generally, these have little effect on the health of a fish. Little can be done to rid a pond of all parasites. Maintaining good water quality and preventing overcrowding of fish is the best way to keep a healthy fish population. If fish flesh is properly cooked, any parasites in the flesh pose no health hazard to humans who consume them.

Fish kills in sportfish ponds are often due to low oxygen concentrations. Several conditions can lead to oxygen depletion. Excessive aquatic vegetation can or occasionly die back, consuming large quantities of oxygen as it decays. The best prevention for this is to maintain aquatic vegetation at a minimum. Floating plants such as duckweed can quickly cover the surface of a pond, preventing photosynthesis and the free exchange of oxygen from the atmosphere into the water. Microscopic plants, called phytoplankton, produce much of the oxygen in ponds. On calm overcast days, the animals and plants in a pond can consume the oxygen faster than the plants can produce it, resulting in oxygen shortages during the night or early morning hours. Heavy mortality can often be prevented by pumping fresh aerated water into the pond or by aeration of the water in the pond.

Runoff from livestock feedlots should not be allowed to enter a pond in excessive quantities. Nutrients in the runoff will promote the growth of rooted aquatic plants and dense algal blooms. In addition, the decaying organic matter will consume large quantities of oxygen. Fish kills may also occur in ponds where high densities of fish are crowded into small shallow areas due to low water levels. Accidental introduction of pesticides into ponds should be prevented. Many agricultural herbicides and insecticides are toxic to fish.

Habitat Management

Muddy Water

Muddy water is not only undesirable aesthetically, but also from a fisheries management point of view. Muddy or turbid water reduces the ability of a pond to produce fish food (microscopic plants and animals) and the ability of sight-feeders such as largemouth bass, crappie, and sunshine bass (striped bass crossed with white bass hybrids) to effectively capture their prey. This can result in reduced growth rates for these predatory species and overpopulation of prey species such as bluegill and redear sunfish.

Water in newly constructed ponds is often muddy. This should clear up as the pond banks become vegetated. Several factors may cause ponds to remain muddy after their construction. These include erosion of soils within the watershed or of the pond banks by wave action, the presence of fine clays in suspension, activity by crayfish or certain fish, and livestock wading along the shoreline.

The cause of the muddy water should first be determined and then controlled. This will allow the pond to clear over time. Planting windbreaks and deepening shallow shoreline areas of the pond will reduce turbidity due to erosion. Livestock can be fenced from a pond and given an alternate source of drinking water. Crayfish are not normally a problem in ponds that have established bass populations because predation of bass on crayfish will often result in reduced crayfish abundance. Nuisance fish such as carp or bullheads can be removed by rotenone as discussed previously in the section on removal of unwanted fish. Shallow ponds with large numbers of catfish will often be muddy. This type of pond is best left alone. Any attempt to clear this type of pond will usually fail as the catfish will continuously stir up the pond bottom.

If the water does not clear, the turbidity could be due to suspended clay particles. This type of water can be quickly cleared by broadcasting either 75 to 100 pounds of ground agricultural gypsum or 5 to 15 pounds of aluminum sulfate (commercial alum crystals) per acre-foot of water.

Hay can also be applied at about two bales per surface acre. The bales should be broken apart and scattered about the surface of the pond. As the hay decays, the clay particles will settle out. The decaying hay will also promote the growth of microscopic plants and animals which are food for small fish. If the pond does not clear, additional hay can be added at a rate of two bales per surface acre every two weeks, not to exceed a total of 10 bales per acre per year. Care must be taken to avoid depleting oxygen in the pond which could lead to a fish kill.

Aquatic Vegetation

Aquatic plants serve many roles in ponds. They produce oxygen which is used by fish and they remove waste nutrients. They provide cover for small fish, spawning habitat for adult fish, and substrate for small aquatic animals which are food for fish (Figure 8). Aquatic plants reduce wind erosion to shorelines by dampening wave action. At times, however, plants may become too abundant, interfering with the recreational use of a pond, including such activities as fishing, boating, and swimming. Excessive plants can also disrupt the ability of predators such as the largemouth bass to capture prey species such as the bluegill. Under such conditions, growth of both of these species will be reduced. In addition, decaying plants consume large quantities of oxygen, which may result in fish kills.

Credit: IFAS Communications Services, Stacey Jones

When ponds are constructed with minimal amounts of shallow water and are relatively fertile, aquatic vegetation is normally not a serious problem. If aquatic vegetation becomes overabundant, three methods of control are available. These include mechanical, chemical, and biological techniques.

Mechanical control may be as simple as cutting plants such as willows or cattails from the dam of a pond or raking submerged plants from a favorite fishing area. Large mechanical harvesters are also available, but are cost-prohibitive and impractical for small ponds. Such devices are generally used to maintain boat trails in larger lakes. Mechanical control is time consuming and its effects are short lived if total control is not achieved.

Chemical control can be an effective means of controlling nuisance aquatic vegetation in a pond. Before using any chemical control, the aquatic plant to be treated must be correctly identified so that the most effective and economical herbicide can be chosen (see Florida Cooperative Extension Service Publication SS-AGR-44, "Efficacy of Herbicide Active Ingredients Against Aquatic Weeds"). Assistance in aquatic plant identification can be obtained from the Florida Cooperative Extension Service and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Specific areas within a pond can be kept free of aquatic vegetation or the entire pond can be cleared. If the pond owner wishes to remove all the vegetation from a pond, only a portion of the vegetation should be treated to minimize the chance of having a fish kill as the dying vegetation decays. After the treated vegetation decays, additional vegetation can then be treated. Always read and observe the herbicide label precautions. After herbicide application, the water and fish may be unfit for food or agricultural purposes until a specified period of time has elapsed. This information will be provided on the herbicide label. Although chemical control is effective, it can be expensive. The herbicides may have to be applied several times during the year.

Biological control of aquatic vegetation can be achieved using herbivorous fish such as the white amur, commonly called the "grass carp". The grass carp is almost totally vegetarian after it reaches a length of about four inches. It prefers to eat pondweeds that contain little fiber, but will consume emergent reeds, rushes, and sedges. In the absence of aquatic vegetation, grass carp feed on terrestrial plants overhanging or falling into the water. A free permit is required to possess grass carp in Florida. The permit must be obtained from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Only sterile triploid fish can be stocked into Florida waters. Recommended stocking rates range from 5 to 25 fish per acre of water. These rates vary depending on the type and quantity of vegetation present. Only eight-inch or larger grass carp should be stocked into ponds with existing bass populations to minimize predation by bass. Grass carp may live more than ten years, making their use a cost-effective means of controlling nuisance aquatic vegetation. For further information, see Florida Experiment Stations Bulletin 867, "Grass Carp, a Fish for Biological Management of Hydrilla and Other Aquatic Weeds in Florida".

Liming

Many Florida ponds are constructed on acid soils. This can cause water to become acid, reducing the efficient use of nutrients, thus decreasing the overall productivity of a pond. Fish are often stressed in low pH (acid) water, causing them to grow slowly. A pH of 7.0 is considered to be neutral, while a pH of 6.0 to 8.0 is considered desirable for maximum fish production.

An acid water (low pH) situation can easily be overcome by liming. Ponds can be limed just as agricultural fields are limed to increase soil pH. One ton of limestone will raise the pH of a one-acre pond by approximately one pH unit.

Only finely ground agricultural limestone should be used. Lime can be applied from a boat over the surface of a pond, or in shallow areas around the perimeter of the pond. Response of the pond water to liming may take four to eight weeks. Frequency of liming varies from pond to pond depending upon the local soil acidity and movement of water into and out of the pond. Your county agricultural extension agent can assist you in determining if and how much lime should be added to your pond (see Florida Cooperative Extension Service FA38, "The Use of Lime in Fish Ponds").

Liming will also increase the total alkalinity and hardness of the water, which will help minimize pH fluctuations and aid in the growth of the fish.

Fertilization

Fertilization, the artificial addition of nutrients to a pond, is not a recommended or necessary management practice for most of central and south Florida. Most soils in these areas are naturally rich in phosphate and any ponds built in these soils are naturally rich in nutrients and highly productive. Ponds in the Florida Panhandle may benefit from fertilization.

Fertilization can be an effective means of controlling submergent aquatic vegetation. If begun early enough in the year, the addition of nutrients to a pond will promote the growth of microscopic plants (Figure 9). Their dense populations will shade the rooted plants, preventing them from growing. Increased risks of having a fish kill exist for any pond with high nutrient loads. In addition, if fertilization is stopped, rooted plants may grow back in even greater abundance than existed before fertilization.

Credit: IFAS Communications Services, Stacey Jones

A fertilization program can also greatly increase the productivity of a pond. Fertilized ponds often maintain two to three times the standing crop (pounds per acre) of fish than unfertilized ponds. Such a program is not warranted unless a pond receives heavy fishing pressure. Contact your County Extension office or your regional Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission office for further information on pond fertilization specific to your locale (see Florida Cooperative Extension Service FA17, "Fertilization of Fresh Water Fish Ponds").

Income from Your Pond

The number of anglers in Florida is rapidly increasing due to the growing interest in fishing and Florida's rapidly growing population. Fishing pressure on our public waters is increasing, with many anglers looking for alternative places to fish. With increasing transportation costs, many anglers are looking for fishing opportunities closer to home. Fee fishing, paying for the right to fish and/or paying for any fish that are caught, is becoming popular among anglers.

There are three basic types of fee fisheries: long-term leasing, day leasing, and pay by the pound operations (see UF/IFAS Extension Circular 809, "Fee Fishing in Florida"). Fishing rights to a private pond or lake can be leased on a long-term basis to an individual or group of individuals such as is done with hunting or grazing leases. Management of the pond is often the responsibility of the lessee. Day leasing involves collecting a daily user fee from the fisherman. Pond management is the responsibility of the operator, who may stock the pond with catchable-size fish, such as channel catfish, on an occasional basis. Normally, however, only those fish that are produced within the pond through natural reproduction are made available to the angler. Generally, largemouth bass-bluegill ponds are used in day leasing operations. "Put and take" or "pay by the pound" fisheries involve stocking a pond with fish and then charging the fisherman for each fish that is caught. Consequently fish populations in this type of operation must be artificially maintained at high levels by regular stocking of catchable-size fish, usually channel catfish.

Fee fishing operations in Florida are rapidly increasing in number, but vary substantially in their success. Little is known as to why this variation occurs and what attracts anglers to these facilities.

References

Cichra, C. E. 1988. Fee Fishing in Florida. Circular 809. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Klinger, R. and R. Francis Floyd. 1987. Introduction to Freshwater Fish Parasites. Circular 716. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Langeland, K., M. Netherland, and W. Haller. 2006. Efficacy of Herbicide Active Ingredients Against Aquatic Weeds. SS-AGR-44. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Lazur, A.M., C.E. Cichra, and C. Watson. 1997. The Use of Lime in Fish Ponds. FA38. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

McGee, M. and C. Cichra. 1988. Catfish Feeds and Feeding. FA1. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Rottmann, R. W. and J. V. Shireman. 1986. Management of Water Quality for Fish. Circular 715. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Sutton, D. L. and V. V. Vandiver, Jr. 1986. Grass Carp, a Fish for the Biological Management of Hydrilla and Other Aquatic Weeds in Florida. Bulletin 867. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Watson, C. and C.E. Cichra. 1990. Fertilization of Fresh Water Fish Ponds. FA17. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.