Bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) is a member of the cucumber family: Cucurbitaceae. This melon is also known as bitter gourd, bitter squash, Goya melon, karela, and balsam pear (Stephens 2012). It is a tropical and subtropical vegetable crop with long climbing vines which is widely cultivated in Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. The fresh fruiting vegetable is one of the most popular vegetables grown in China, India, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam. It has also been grown as a minor vegetable in tropical and subtropical regions of the United States including parts of Florida (Stephens 2012). The unripe fruit is used as a vegetable with a pleasantly bitter taste.

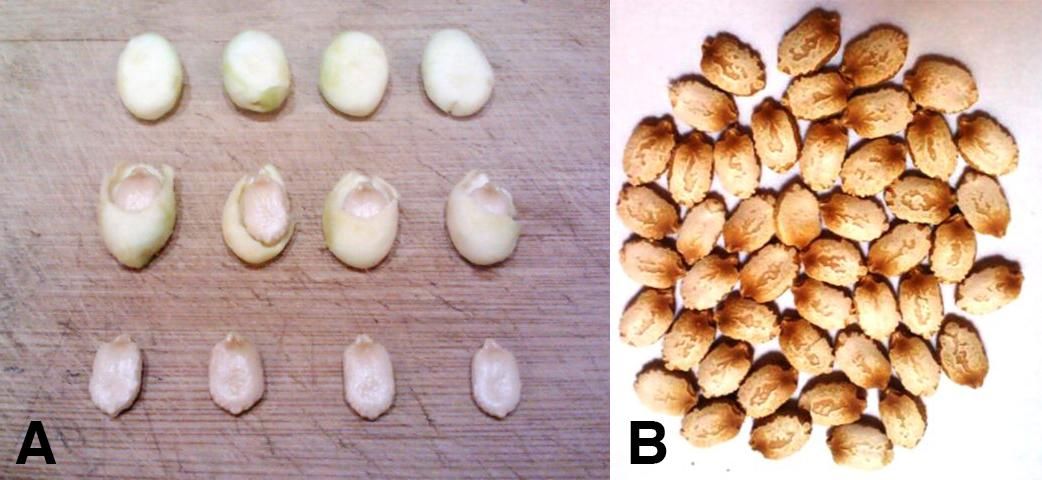

This crop is propagated via seeds with stiff testae (seed coats) which need warm (60–95°F) and moist soil conditions for germination (Figure 1). It may fail or take a long time to germinate if the soil is dry or the temperature is not high enough. Bitter melon is a dicotyledonous species that grows vines up to 16 feet long with many branches. After germination, the first pair of true leaves is round; the others are simple and alternate leaves measuring 2 to 5 inches across, with three to seven deeply separated lobes. Once the plant has grown four to six leaves, its vines start bearing tendrils for climbing (Figure 2). A trellis support system is necessary for high yield and quality bitter melon production. The trellis system is usually 6 feet high (Figures 3 and 4).

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Yuqi Cui, UF/IFAS

Credit: Qingren Wang, UF/IFAS

In Florida, bitter melon starts blooming approximately four weeks after seeding. Each plant bears both male (Figure 5) and female (Figure 6) flowers separately. Bitter melon is a cross-pollinating species and needs insects, such as bees, to carry out the pollinating process for setting fruit. When pollinators are lacking, manual pollination (i.e., picking up male flowers and transferring pollens to female flowers) can be an option for bitter melon production in backyards or small gardens. Female flowers have a baby fruit between the flower and the vine stem (Figure 6). This pollination should be completed during the daytime when flowering is active. If the pollination is successful, the baby fruit will grow into a full-size fruit.

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

There are two types of bitter melon: Chinese variety and Indian variety, named due to the preference of these varieties in China and India, respectively. The former is longer and larger in size (usually 8 to 12 inches in length and 2 to 3 inches in diameter), smooth, light green in color, and oblong-shaped with a distinct warty appearance. The latter is shorter and smaller in size with rough skin, dark green coloration, and pointed ends. Both types have ridges, but Chinese bitter melon ridges are smooth (Figure 7), and Indian bitter melon ridges are pointed (Figure 8).

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

According to the USDA-ARS National Nutrient Database, bitter melon is an excellent source of vitamin C, folate (vitamin B9), and other nutrients such as zinc and potassium (Table 1). Bitter melon fruit are harvested when the fruit is green or slightly yellow. They are cut into halves and the seeds are removed and discarded. The sliced fruit is then consumed with stir-fry cooking (Figure 9). The fruit flesh is often used in Chinese cuisine with sliced garlic, chicken eggs, pork, or "douchi," a type of fermented and salted black soybean (Figure 10). In Indian dishes, the sliced fruit is marinated in a solution of salt and tamarind before being pan-fried with spices.

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

Bitter melon has been used in Asian and African herbal medicine systems for a long time. Ethnobotanical uses in India suggest that this crop can lower blood sugar levels in diabetic patients (Paul and Raychaudhuri 2010). There are also studies that show its efficacy against various cancers such as breast cancer, choriocarcinoma (a fast-growing form of cancer that occurs in a woman's uterus), Hodgkin's disease, human bladder carcinomas, lymphoid leukemia, lymphoma, melanoma, prostate cancer, skin tumor, and squamous carcinoma of the tongue and larynx (Grover and Yadav 2004). Bitter melon extracts are also reported to have anti-obesity effects as well as other medicinal effects (Wang and Ryu 2015).

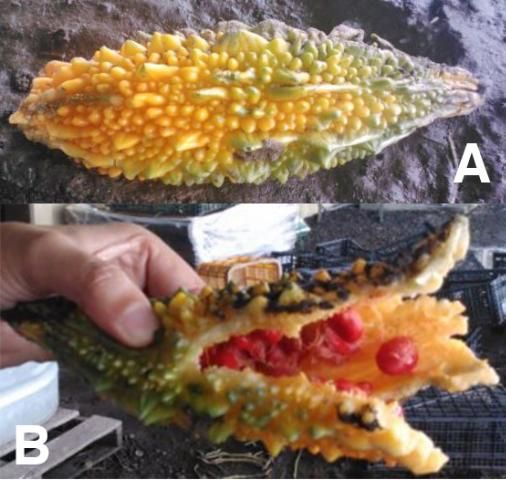

Bitter melon is relatively new to most Floridians, particularly in north Florida, but certain growers have been cultivating this crop for several years. This crop can be direct seeded or transplanted. Direct seeding dates are usually from February to April and July to early August for the spring and fall growing seasons in north Florida. The corresponding dates for central Florida are from January to March and early September to February. For south Florida, it can be seeded from September through February. Distance between rows should be 5 to 6 feet and spacing between plants should be between 3 and 5 feet (Freeman et al. 2015). Fruit should be harvested approximately 50 days after seeding in north Florida. For central and south Florida, fruit can be harvested earlier after seeding. Transplanting can expand the growing season and make the fruit available earlier. This early availability of fruit is beneficial to growers' profitability. If harvested at maturity, fruit turns from green to orange. The seed cover, or aril tissue, turns bright red (Figure 11) and starts to taste sweet. If harvested too late, the fruit opens naturally at the fruit end, and seeds may drop onto the ground. Disease control recommendations can be found in the EDIS publication entitled Diseases of Bitter Melon in South Florida (Zhang et al. 2019, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pp300). Fertilization recommendations for this crop are not available. Growers are suggested to apply fertilizers based on commercial cucumber production: N 150 lb/A; P2O5 and K2O both are the same, 120, 100, and 80 lb/A for very low, low, and medium, respectively (Liu et al. 2).

Credit: Guodong Liu, UF/IFAS

References and Further Reading

AgriFarming. 2015. "Bitter gourd farming information guide." #1 Source for Farming in India. Accessed June 9, 2022. http://agrifarming.in/bitter-gourd-farming

Behera, T. K., S. Behera, L. K. Bharathi, K. J. John, P. W. Simon, and J. E. Staub. 2010. Bitter Gourd: Botany, Horticulture, Breeding. Horticultural Reviews (ed. J. Janick.) 37: 101–41. Accessed June 9, 2022. https://www.growables.org/informationVeg/documents/BitterGourdBreeding.pdf

Beloin, N., M. Gbeassor, K. Akpagana, J. Hudson, K. De Soussa, K. Koumaglo, and J. T. Arnason. 2005. "Ethnomedicinal uses of Momordica charantia (Cucurbitaceae) in Togo and relation to its phytochemistry and biological activity." Journal of Ethnopharmacology 96: 49–55.

Chen, Q., L. L. Chan, and E. T. Li. 2003. "Bitter melon (Momordica charantia) reduces adiposity, lowers serum insulin and normalizes glucose tolerance in rats fed a high fat diet." The Journal of Nutrition 133: 1088–93.

Freeman, J. H., E. J. McAvoy, P. J. Dittmar, M. Ozores-Hampton, M. Paret, Q. Wang, C. F. Miller, and S. E. Webb. 2021. Cucurbit production. HS725. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Accessed June 9, 2022. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/cv123

Grover, J. K., and S. P. Yadav. 2004. "Pharmacological actions and potential uses of Momordica charantia: A review." Journal of Ethnopharmacology 93: 123–32. Accessed June 9, 2022. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S037887410400159X

Lim, T. K. 2013. Edible medicinal and non-medicinal plants. Dordrecht: Springer. 331–32.

Liu, G. D., E. H. Simonne, K. T. Morgan, G. J. Hochmuth, S. Ageharas, Rao Mylavarapu, and Phillip Williams. 2021. Chapter 2. Fertilizer management for vegetable production in Florida. CV296. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Accessed June 9, 2022. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/CV296

Lo, H. Y., T. Y. Ho, C. Lin, C. C. Li, and C. Y. Hsiang. 2013. "Momordica charantia and its novel polypeptide regulate glucose homeostasis in mice via binding to insulin receptor." Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 61:2461–8.

Ooi, C. P., Z. Yassin, and T. A. Hamid. 2012. "Momordica charantia for type 2 diabetes mellitus." The Cochrane Library 8: CD007845.

Palada, M. C., and L. C. Chang. 2003. "Suggested cultural practices for bitter gourd." International Cooperators' Guide. Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center (AVRDC) pub# 03-547. 1–5. Accessed June 9, 2022. https://growables.com/informationVeg/documents/BitterGourdCulturalAVRDC.pdf

Paul, A., and S. S. Raychaudhuri. 2010. "Medicinal uses and molecular identification of two Momordica charantia varieties – A review." Electronic Journal of Biology 6: 43–51.

Stephens, J. M. 2012. Momordica—Momordica spp. HS627. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Accessed June 9, 2022 https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mv094.

USDA-ARS. 2015. National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 28, Full Report (All Nutrients) 11025, Balsam-pear (bitter gourd), pods, cooked, boiled, drained, without salt. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/168394/nutrients

Wang, J., and H. K. Ryu. 2015. "The effects of Momordica charantia on obesity and lipid profiles of mice fed a high-fat diet." Accessed June 9, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26425278

Zhang, S., M. Lamberts, and E. McAvoy. 2012. Diseases of bitter melon in south Florida. PP300. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Accessed June 9, 2022. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pp300