Root weevils infest citrus groves throughout the citrus growing regions of Florida. Among the eight weevil species that have been identified in Florida citrus groves, five have some potential to cause economic problems for nurserymen and commercial growers. The most important weevil species are Diaprepes root weevil (Diaprepes abbreviatus), southern blue-green citrus root weevil (Pachnaeus litus), and the blue-green citrus root weevil (Pachnaeus opalus). The little leaf notcher (Artipus floridanus) and Fuller rose beetle (Asynonychus godmani) are of less concern, but may be locally important (Figure 1). This paper will deal with Diaprepes and the blue-green root weevils because they are of major economic importance and frequently occur in citrus groves. Adult Diaprepes, the largest of the above-mentioned weevils, is approximately 1/3 to 3/4 inch in length, whereas the blue-green root weevils are slightly smaller, approximately 1/3 to 1/2 inch in length. Weevils feed on a wide range of plants estimated at more than 275 species.

Credit: UF/IFAS CREC

Leaf Symptoms

The most obvious symptom of weevil presence in a grove is the notching of the leaf by adults. The damage to the young tender foliage is confined to the margin of the leaf (Figure 2). The degree of notching is dependent on the species of weevil present, weevil abundance, and availability of young foliage as a food source. The larvae are the most destructive life stage. They reside in the soil where feeding on the roots over time affects the vitality and productivity of the tree. The larval feeding also predisposes the roots to easy entry by Phytophthora species, further compounding the damaging affect of the weevil.

Credit: UF/IFAS CREC

Tree canopy symptoms associated with extensive larval feeding on the roots are similar to other tree declines, and includes leaf yellowing, leaf drop, twig dieback, off-bloom, or a general thinning canopy in addition to lack of response to irrigation due to damaged roots.

Adult Diaprepes and blue-green weevils are capable of flying short distances. Adult weevils aggregate on new foliage, feed on new flush, mate, and lay eggs on young or mature foliage. Weevils feed on the outer foliage until midday and then move to the inner canopy to avoid the heat. The best time to survey for weevils is early in the morning or late in the afternoon by inspecting young foliage. Since the weevils will fall from the tree when disturbed, growers can use several devices to determine if they are present. One of the easiest methods for detection is to shake the branches to dislodge the weevils. Before shaking the branches several times, a large golf-type umbrella is placed upside down on the ground beneath an area of the tree with young foliage where weevils may be feeding (Figure 3). Plastic sheeting or a drop cloth can also be used. The process of dislodging the weevils should be repeated in several locations around the tree. The number of weevils captured by this method will define their seasonal abundance.

Credit: UF/IFAS CREC

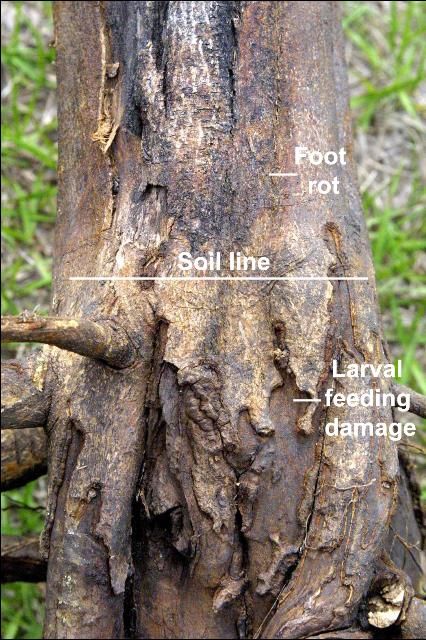

Root Symptoms

Growers can routinely inspect the root system of trees when they are removed from the ground to determine if weevils have been present and to determine the extent of feeding damage to the roots. To improve detection of damage, the root system may need to be washed free of soil. If weevil larvae have been present, channeling on the roots will be noticeable (Figure 4). Although it is not possible to determine the type of weevil that causes the root damage, the more severe the damage the greater the likelihood it is caused by Diaprepes. While inspecting the root system, look for sloughing of root bark caused by Phytophthora infection that may be associated with the bark channeling (Figure 5). In flatwood soils where trees have shallow root systems, larva damage appears to be more pronounced.

Credit: UF/IFAS CREC

Credit: UF/IFAS CREC

Monitoring

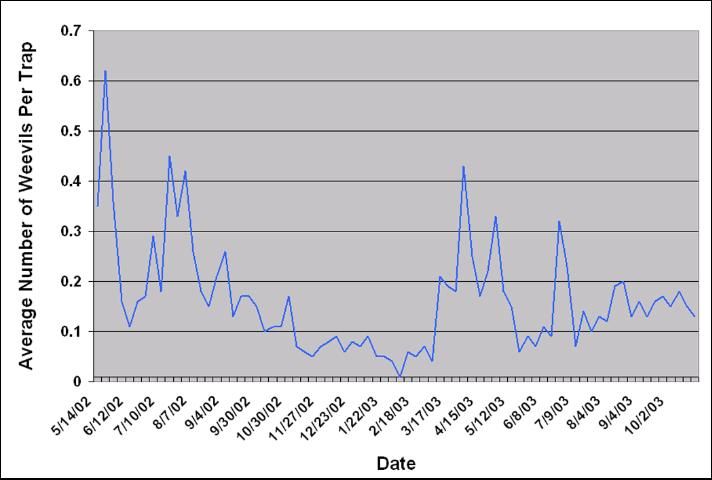

The most commonly used method to determine weevil abundance over time is to place Tedders traps in the grove and monitor captured weevils on a weekly basis. A Tedders trap is an unbaited pyramidal shaped, non reflective silhouette device that mimics a citrus tree trunk (Figure 6) where they are trapped in upper screen enclosure. Adults crawl up the trunk to gain access to young foliage. Researchers generally place 50 to 100 Tedders traps per grove location to determine seasonal adult abundance patterns. The number of weevils trapped can vary greatly from grove to grove and between seasons. When weevil numbers emerging from the soil reach a peak, and the trees are flushing, a pesticide can be applied to reduce the number of egg laying females. The peak adult populations in central Florida occurs in June whereas on the east coast in May. Some emergence occurs throughout the remainder of the year with a second peak sometime occurring in September-October (Figure 7).

Credit: UF/IFAS CREC

Credit: UF/IFAS CREC

Life Cycle

The life cycle for all root weevils is similar, consisting of three immature stages: eggs (on leaves), larvae, and pupae in soil. Following pupation, the adult may remain in the soil for a few weeks before emerging and locating a host where it begins feeding on foliage, mating and females laying eggs between leaves. All weevils, except Fuller rose weevil, deposit their eggs in a mass between two leaves that are held together by an adhesive substance secreted by the female at the time of egg laying. The eggs are smooth, white, and oblong-oval. Egg size and number vary by species. The Fuller rose weevil lays its eggs beneath the calyx of fruit or in cracks formed by leaves or on the bark of the tree.

Eggs usually hatch into neonate larvae within 7 to 20 days, depending on temperature, environmental conditions, and species. The neonate larvae soon fall to the soil surface and immediately move into the soil where they feed on fibrous roots of the tree. Larvae have difficulty penetrating dry soil. Predation of larvae by ants, earwigs, and other insects on the soil surface is common in some groves. Some nematode species also cause larvae mortality. The larvae are legless, white, and have chewing mouthparts (Figure 8). As the larvae increase in size, they move from the fibrous roots and feed on the larger lateral or pioneer roots. Larval feeding causes damage to the outer bark tissue into the cambium layer of the root and may girdle and kill a root. Root function is decreased due to root damage and the tree's vigor is likewise reduced. The time to complete larval development varies, depending on environmental conditions and food availability, from as short as 40 days for the little leaf notcher to as long as up to a year or more for Diaprepes. As the larvae complete their development, they pupate in the soil. Adults may emerge from the soil quickly or may remain in the soil for three to four weeks. Adult emergence from the soil can be triggered by rainfall.

Credit: UF/IFAS CREC

Weevils can move from grove to grove on equipment or in nursery trees. Thus, sanitation and thorough inspection are important control measures to minimize the spread of weevils.

For additional information on recommendations for weevil management, please consult the Florida Citrus Production Guide which is published annually by the University of Florida or may be obtained online at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/CG006.