The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids, and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Parapoynx diminutalis Snellen is an adventive Asian moth with an aquatic larval stage. The moth is found associated with a variety of water bodies including river backwaters, lakes, and ponds (Habeck 1996). The aquatic larvae commonly attack hydrilla, Hydrilla verticillata (L.f. Royle), and other aquatic plants (Buckingham and Bennett 1989, 1996).

The moth was identified in 1971 in India and Pakistan during scouting trips to attempt to determine potential biological control agents for hydrilla. Despite having potential for hydrilla destruction, the moth was declared to be a generalist feeder and unsuitable for release into US water bodies for hydrilla control (Baloch et al. 1980). However, the moth was later found in Florida in 1976 by United States Department of Agriculture technicians who were testing herbicides for hydrilla control. The larvae (caterpillars) found on hydrilla were observed to be eating the invasive weed. The pathway, method, or time of the moth's arrival remains unknown (Del Fosse et al. 1976).

Synonymy

According to the global Pyraloidea database (Nuss et al. 2003–2013) and Shibuya (1928) the following junior synonyms have been used for Parapoynx diminutalis:

Parapoynx dicentra Meyrick (1885)

Oligostigma pallida Butler (1886)

Nymphula diminutalis Meyrick (1894)

Nymphula uxorialis Strand (1919)

Distribution

Parapoynx diminutalis is native to parts of Asia, Africa, and Australia (Buckingham and Bennett 1996). In its adventive range, Parapoynx diminutalis has been found in Panama (notably in the Panama Canal, which was infested with hydrilla), Honduras, and Florida. In commercial greenhouses, the moth has been observed colonizing aquatic plants in England and Denmark (Agassiz 1978, Agassiz 1981). Parapoynx diminutalis was first seen in Florida in Fort Lauderdale in 1976 but progressively appeared in more northern counties, eventually reaching Alachua and Putnam counties by 1979 (Balciunas and Habeck 1981). In the early 1980s, hydrilla surveys in other southeastern states revealed that the moth's range did not extend beyond Florida (Balciunas and Minno 1985). More recent studies indicate that the moth is established in Louisiana, where 37 moths were collected from 1984–1992 (Brou Jr. 1993).

Even in northern Florida, the cooler water temperatures caused populations to be reduced in late winter and early spring. Milder climates such as those found in Panama may enable populations to thrive throughout the year (Buckingham and Bennett 1996).

Description

Eggs

Eggs are smooth and bright yellow when laid (Figure 1); they turn white, and then become transparent as they develop. The eggs are generally deposited on plant leaves or stems just below the water surface in masses of various sizes (Buckingham and Bennett 1996).

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

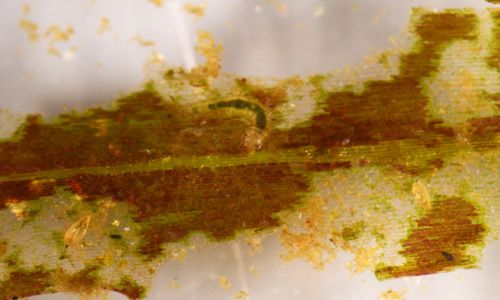

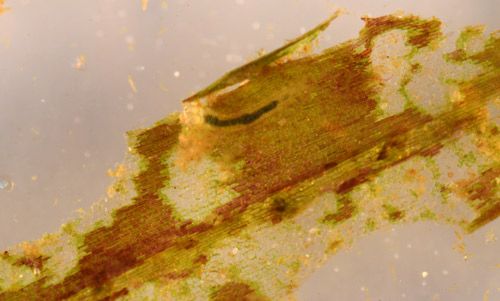

Larvae

Larvae can be distinguished from those of other aquatic species by the presence of branched gills (Habeck 1996) and brown spots on the head and the tip of the thorax. The larval stage consists of seven instars; all seven are off-white with yellow-brown legs (Habeck and Balciunas 2005). The larvae are mobile and feed on hydrilla leaves. The first instar is white yet nearly transparent and has 1 mm long setae (hairs) (Figure 2). Instars 2 through 7 are white, later instars begin to turn yellow as they approach pupation (Figure 3). In later instars, the length increases, and the external gills develop (Figure 4). Instars 3 through 7 use plant tissue to construct a silk case, and often retreat into the case between feeding events (Buckingham and Bennett 1996).

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Credit: Julie Baniszewski, UF/IFAS

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Pupae

Pupae have three tubercles (or nodules) along each side and two setae (or hairs) on the head. Female pupae can be distinguished from males by their larger size and by their antennae. Female antennae are shorter, extending only to the wing tips, whereas male antennae are longer and extend past the wing tips (Buckingham and Bennett 1996). Late seventh instar larvae (or pre-pupae) enclose themselves in a white cocoon, which is attached to a submerged plant stem (Figure 5). After 1–2 days in the cocoon, the white pre-pupae have developed into yellow pupae inside the cocoon. The eyes turn red, then brown, and the wings become visible as pupation progresses (Buckingham and Bennett 1996).

Credit: Julie Baniszewski, UF/IFAS

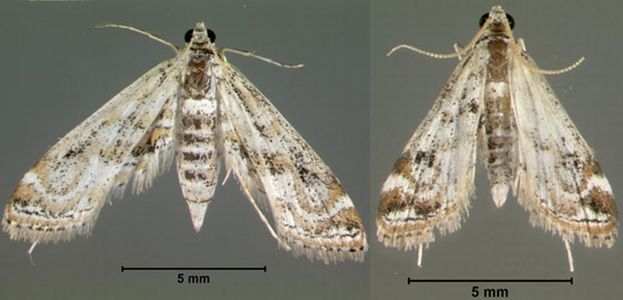

Adults

Moth adults are white with brown or tan markings or bands on the wings and tan bands on the body (Figure 6). Females typically differ from males by their longer wingspans, more pointed forewings, larger abdomens, and shorter antennae, and they lack the noticeable white setae displayed by males on the tip of the abdomen (Buckingham and Bennett 1996).

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Life Cycle and Biology

Parapoynx diminutalis undergoes complete metamorphosis from an aquatic caterpillar to a moth. Life stages include the egg, seven larval instars (the seventh instar includes a pre-pupa stage), the pupa, and finally adult emergence (Buckingham and Bennett 1996). The life cycle of Parapoynx diminutalis ranges from 25 to 41 days for development and about five days for the adult life span. Females lay on average about 200 eggs but can lay just a few to over 500. The eggs require 4–6 days to develop before the first instars hatch. Adults typically emerge from pupae after dusk and are quick to fly to avoid potential predators. The adults drink water using a reduced proboscis, but they do not appear to feed (Buckingham and Bennett 1996). Parapoynx diminutalis mating has not been studied in detail but has been observed occasionally and seems to occur at around three hours after dusk. Although the maximum time in copula is unknown, pairs of moths in copula facing in opposite directions were noted to rest for at least 30 minutes. After mating, there is a one-day pre-oviposition period. Females then oviposit soon after dusk just below the water surface on leaves or stems. First instars have been shown to hatch both below and above the water surface, although it has been observed that the females typically oviposit below the water surface (Buckingham and Bennett 1996).

Hosts

Larvae are commonly found on the aquatic weed hydrilla, Hydrilla verticillata. The initial discovery of the moth on hydrilla led to an interest in the moth as a possible biological control agent of this invasive weed. In the field, larvae and pupae have been found in small numbers on coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum L.), southern naiad (Najas guadalupensis (Sprengel) Magnus), and Illinois pondweed (Potamogeton illinoensis Morong) (Buckingham and Bennett 1996). Furthermore, in laboratory studies, while Parapoynx diminutalis larvae preferred hydrilla, they could also complete development on various other plants including coontail, southern naiad, fanwort (Cabombo caroliniana Gray), Brazilian waterweed (Egeria densa Planchon), and Eurasian water-milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum L.) (Buckingham and Bennett 1989).

Damage

Plant damage is inflicted by the larvae, which not only eat the leaf and stem tissue, but use these materials to prepare their pupal cocoon as well (Figure 7). The main food source for Parapoynx diminutalis is the aquatic weed hydrilla (Buckingham and Bennett 1996). In most natural situations in the US, hydrilla is invasive and an undesirable weed because it develops surface mats and disrupts natural ecosystems (Haller and Sutton 1975; Langeland et al. 2016). There have been few studies to quantify the effect of feeding moth larvae on hydrilla biomass. One study found that fifth instar larvae damaged approximately 10 growing tips of hydrilla per larvae during a 19 day experiment (Stachowiak et al. 2021).

Feeding of the moth larvae on hydrilla in Florida was thought to have a positive effect on hydrilla-invaded water bodies (Del Fosse et al. 1976) by reducing the need for herbicide applications to control hydrilla mats. However, naturalized populations of this moth are too sporadic to have a significant effect on hydrilla density. For example, in northern Florida populations build up during the summer months and can cause extensive defoliation of hydrilla, but in the winter, populations decline rapidly with cooler water temperatures (Buckingham and Bennett 1996).

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Importance as a Biological Control Agent

The moth was identified in Pakistan and India during scouting trips to locate potential biological control agents for hydrilla (Baloch et al. 1980). At this point, the researchers observed the moth damaging hydrilla and believed that the moth could be an effective control agent due to its destructive capabilities. Further scouting activity from 1996–2013 in Asia and Australia recovered the moth from hydrilla in China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam (Purcell et al. 2019).

An important characteristic of a biocontrol agent is host specificity. When laying eggs, female Parapoynx diminutalis are not highly selective, which makes other plants susceptible to consumption by developing larvae. Furthermore, the moth is limited by winter temperatures, and populations decline during the cooler months to a level that is almost undetectable. Sensitivity to cooler climates and lack of host specificity makes the moth a poor biological control agent of hydrilla (Habeck and Balciunas 1976; Buckingham and Bennett 1989).

However, in South Africa, where the moth was accidentally introduced, Parapoynx diminutalis is believed to be having a significant impact on hydrilla infestations (Bownes 2010, 2019). After moths were discovered feeding in a hydrilla infested water body at Pongolapoort Dam, KwaZulu-Natal in January 2009, almost all plants were defoliated by April of the same year (Bownes 2010). The moth populations were observed to closely follow the growth patterns of the hydrilla, causing significant damage and reduction in the aquatic weed (Bownes 2019). Although hydrilla was not eradicated in this area, the reduction in viability of the hydrilla in Florida has allowed other native plants to recolonize.

Monitoring/Management

Monitoring for adult moths can be done using ultraviolet (UV) black lights or incandescent light bulbs, which are both attractive to the moth (Buckingham and Bennett 1996).

Hydrilla is invasive, and the actions of the moth rarely require management and are usually considered to be desirable. However, in certain situations where the presence of hydrilla is needed, such as in research with other biocontrol agents, management of the moth larvae may be necessary to prevent consumption of the plant material. In these situations, a strain of the biorational insecticide Bacillus thuringiensis has been tested for controlling Parapoynx diminutalis (Buckingham and Bennett 1996; Bownes 2010; Baniszewski et al. 2016). Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies kurstaki, commonly known as Btk, is specific to lepidopteran pests. Btk produces proteins that are toxic to larvae; the proteins bind to the midgut when consumed and kill the larvae (Bauce et al. 2006; Van Driesche et al. 2008). A commercially available Btk product has been shown to cause 80% mortality of Parapoynx diminutalis larvae in about four days (Buckingham and Bennett 1996). Baniszewski et al. (2016) found that a concentration of 2 mL per 3.8 L or higher reduced moth emergence by 75% and a concentration of 0.2 mL per 3.8 L reduced emergence by 50%. However, the higher concentrations impacted the emergence of the biological agent under culture, the hydrilla tip-mining midge, Cricotopus lebetis Sublette (https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/aquatic/hydrilla_tip_mining_midge.htm) (Diptera: Chironomidae) (Baniszewski et al. 2016). A study by Stachowiak et al. (2021) where the moth was applied to hydrilla-filled tanks in combination with the hydrilla tip-mining midge found that the moth alone had no negative effect on the midge’s development.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding provided by the USDA NIFA RAMP Grant 2010-02825 that helped pay for the production of this article. The authors would like to acknowledge the reviewers that provided feedback on an early draft of the article, Dr. William Overholt and Dr. Verena Lietze.

Selected References

Agassiz, D. 1978. "Five introduced species, including one new to science, of China mark moths (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) new to Britain." Entomologist's Gazette 29: 117–127.

Agassiz, D. 1981. "Further introduced China mark moths (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) new to Britain." Entomologist's Gazette 32: 21–26.

Balciunas, J. K., and D. H. Habeck. 1981. "Recent range extension of a hydrilla damaging moth, Parapoynx diminutalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae)." Florida Entomologist 64: 195–196.

Balciunas, J. K., and M. C. Minno. 1985. "Insects damaging hydrilla in the USA." Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 23: 77–83.

Baloch, G. M., Sana-Ullah, and M. A. Ghani. 1980. "Some promising insects for the biological control of Hydrilla verticillata in Pakistan." Tropical Pest Management 26: 194–200.

Baniszewski, J., E. N. I. Weeks, and J. P. Cuda. 2016. "Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies kurstaki reduces competition by Parapoynx diminutalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) in colonies of the hydrilla biological control agent Cricotopus lebetis (Diptera: Chironomidae)." Florida Entomologist 99: 644–647.

Bauce, E., M. Kumbasli, K. Van Fankenhuyzen, and N. Carisey. 2006. "Interactions among white spruce tannins, Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki, and spruce budworm (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae), on larval survival, growth and development." Journal of Economic Entomology 99: 2038–2047.

Bownes, A. 2010. "Asian aquatic moth Parapoynx diminutalis, accidentally introduced earlier, contributes to control of an aquatic weed Hydrilla verticillata in South Africa." African Journal of Aquatic Science 35: 307–311.

Bownes, A. 2019. "Suppression of the aquatic weed Hydrilla verticillata (L.f.) Royle (Hydrocharitaceae) by a leaf-cutting moth Parapoynx diminutalis Snellen (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) in Jozini Dam, South Africa." African Journal of Aquatic Science 43: 153–162.

Brou, Jr V. A. 1993. "Range extension of the moth Parapoynx diminutalis Snellen (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae)." Southern Lepidopterists' News 15: 33–34.

Buckingham, G. R., and C. A. Bennett. 1989. "Laboratory host range of Parapoynx diminutalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), an Asian aquatic moth adventive in Florida and Panama on Hydrilla verticillata (Hydrocharitaceae)." Environmental Entomology 18: 526–530.

Buckingham, G. R., and C. A. Bennett. 1996. "Laboratory biology of an immigrant Asian moth, Parapoynx diminutalis (Lepidotera: Pyralidae), on Hydrilla verticillata (Hydrocharitaceae)." Florida Entomologist 79: 353–363.

Del Fosse, E. S., B. D. Perkins, and K. K. Steward. 1976. "A new record for Parapoynx diminutalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), a possible biological control agent for Hydrilla verticillata." Florida Entomologist 59: 1–30.

Haag, K. H., and Buckingham G. R. 1991. "Effects of herbicides and microbial insecticides on the insects of aquatic plants." Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 29: 55–57.

Habeck, D. H. 1996. Australian moths for hydrilla control. Vicksburg, MS: U.S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station. Technical Report. A96: 10, Vicksburg, MS.

Habeck, D. H., and J. K. Balciunas. 2005. "Larvae of Nymphulinae (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) associated with Hydrilla verticillata (Hydrocharitaceae) in North Queensland." Australian Journal of Entomology 44: 354–363.

Haller, W. T., and D. L. Sutton . 1975. "Community structure and competition between hydrilla and vallisneria." Hyacinth Control Journal 13: 48–50.

Kegley, S. E., B. R. Hill, S. Orme, and A. H. Choi. 2010. PAN pesticide database. Pesticide Action Network, North America (San Francisco, CA. 2010). (17 April 2023).

S. F. Enloe, L. Gettys, J. Leary and K. A. Langeland. 2016. Hydrilla Management in Florida Lakes. SS-AGR-361. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ag370 (17 April 2023)

Nuss, M., B. Landry, F. Vegliante, A. Tränkner, R. Mally, J. Hayden, A. Segner, H. Li, R. Schouten, M. A. Solis, T. Trofimova, J. De Prins, and W. Speidel. 2003–2013. Global information system on Pyraloidea. (17 April 2023).

Purcell, M., N. Harms, M. Grodowitz, J. Zhang, J. Ding, G. Wheeler, R. Zonnevald, and R. Desmier de Chenon. 2019. "Exploration for candidate biological control agents of the submerged aquatic weed Hydrilla verticillata, in Asia and Australia 1996–2013." BioControl 64: 233–247.

Shibuya, J. 1928. The systematic study on the Formosan Pyralidae. Journal of the Faculty of Agriculture, Hokkaido Imperial University, Sapporo, Japan 22: 1–300.

Stachowiak C, Baniszewski J, Cuda, JP, St Mary C, Weeks ENI. 2021. Influence of competition and predation on survival of the hydrilla tip mining midge and its success as a potential augmentative biological control agent of hydrilla. Hydrobiologia 848: 581-591.

Van Driesche, R., M. Hoddle, and T. Center. 2008. Control of Pests and Weeds by Natural Enemies: An Introduction to Biological Control. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.