Introduction

Insects of the family Chironomidae, commonly known as midges, are often the most abundant group of insects inhabiting freshwater environments (Pinder 1986). Midges are fragile and mosquito-like in appearance, but they do not bite. Larvae of most midges are aquatic and feed primarily on algae and decaying organic matter. A few species, however, are capable of mining the soft tissues of submersed plants and using the living plant material as a food source (Pinder 1986). Recently, this feeding strategy has been studied in some detail in the genus Cricotopus because of the realization that it could be exploited for the biological control of the exotic aquatic weed Eurasian watermilfoil, Myriophyllum spicatum L. (MacRae et al. 1990), and possibly hydrilla, Hydrilla verticillata (L.f.) Royle (Cuda et al. 2002; Cuda et al. 2011).

Hydrilla is a submersed aquatic plant endemic to the Old World tropics; it was introduced into Florida by the aquarium industry in the late 1950s (Langeland 1990). Evidence from a molecular study point to Bangalore, India as a possible origin of the hydrilla population in Florida (Madeira 1999). After its discovery in the Crystal River watershed in 1960, hydrilla continued to expand its range statewide and to increase in severity in water bodies already infested. The dense surface mats associated with severe hydrilla infestations cause problems because they hinder navigation and flood control, interfere with recreational activities, and reduce the biodiversity in aquatic ecosystems (Haller 1978). Between 1982 and 2020, approximately $331 million in state and federal funds were spent managing hydrilla in Florida public waters (FWC 2020). In the year 2019–2020, approximately $9 million was spent treating around 16,000 acres of hydrilla (FWC 2020). The discovery of herbicide resistance in hydrilla in 2004 (Michel et al. 2004), led to renewed interest in biological control.

In 1992, USDA researchers discovered midge larvae attacking the apical meristems of hydrilla in the Crystal River watershed in Citrus County, Florida (G.R. Buckingham, personal communication), and that the damaged hydrilla at one site was stunted and unable to grow to the surface. The hydrilla-attacking midge was subsequently identified as Cricotopus lebetis Sublette (Figure 1), a species possibly new to Florida (Epler et al. 2000). Because previous research implicated midge larvae as causal agents of damaged stem tips on stunted hydrilla plants in Africa (Markham 1986), it was suspected that this tip mining midge may have some potential as a biological control agent.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Synonymy

According to NCBI Taxonomy, Species 2000, and the Integrated Taxonomic Information System, the following synonyms have been used to describe Cricotopus lebetis:

Cricotopus tricinctus Meigen, 1818

Cricotopus hyalinus Kieffer, 1921

Distribution

The midge genus Cricotopus is represented in North America by four subgenera (Epler 1995). Two of these subgenera, Cricotopus and Isocladius, occur in Florida and contain at least eight species (Epler 1995). The actual distribution of Cricotopus lebetis will not be known with any certainty until it can be determined if it is an immigrant that was accidentally introduced along with hydrilla, or an indigenous species that has developed a new association with hydrilla. However, Cricotopus lebetis was found to be widely distributed in Florida from the northern peninsula (Lake Rowell, Bradford Co.) to the south-central part of the state (Lake Istokpoga, Highlands Co.) (Stratman et al. 2013b).

Description

Adult

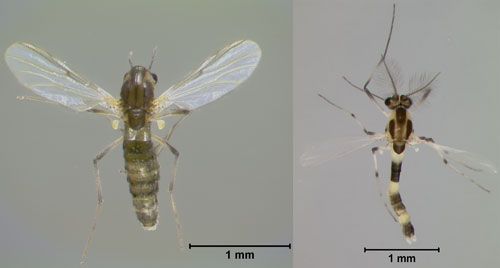

The adult midge is small, only 3 to 4 mm in length, and fragile (Figure 2). Both sexes are pale green in color with black markings on the thorax and a pair of adjacent dark bands on abdominal segments 2 and 3, and 5 and 6. The black markings on the thorax and the coarse banding pattern on the abdomen give the midge a darker appearance. The sexes can be readily distinguished by the condition of the antennae and the shape of the abdomen. In females, the antennae are short and the abdomen is as wide as the thorax. In contrast, the males possess long antennae with distinct whorls of hair and have a narrow, tapering abdomen.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Eggs

The eggs are laid in a linear-shaped mass, containing 50 to 250 eggs diagonally arranged in one or two rows encased in a sticky gelatinous tube (Figure 3). The eggs are white in color when first laid and resemble a string of pearls. Within 24 hours, the eggs that have been fertilized turn grayish-brown, and red eyespots of the fully formed embryo appear just prior to hatching. Often, eggs of C. lebetis are refrigerated to delay development, especially during shipment to field release sites (Baniszewski et al. 2015). In these cases, it is recommended not to refrigerate the eggs for more than 2 days, as it has been shown to result in significant mortality of the immature stages (Baniszewski et al. 2015).

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/UFAS

Larvae

The larvae of Cricotopus lebetis can be identified by the color and general appearance of the body. Live or freshly preserved specimens have a characteristic green body color with a broad dark blue band around the thorax. After the body color fades in preserved specimens, the larvae can be separated from other midge larvae by the presence of a pair of lateral setae on each abdominal segment. The first, second, third, and fourth instars are indicated by peak head capsule widths of 0.09, 0.15, 0.20, and 0.30 mm, respectively (Cuda et al. 2002). Overall body length has been reported by Baniszewski et al. (2015) to be approximately 0.50 mm at 7 days post hatching from the egg.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Pupa

The pupa is a non-feeding stage. The wings and other adult features that have been developing internally are visible (Figure 5). Pupae of C. lebetis possess distinctive breathing horns or "trumpets" that are usually present on the prothorax. The shape of the trumpet can be used to identify the species. In C. lebetis, these horns are fusiform or spindle shaped. A pupa destined to become an adult female of Cricotopus lebetis will have a full complement of eggs visible in the abdomen.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Life Cycle

Adult midges live from one to three days and do not feed. They mate on a suitable substrate during the day (Figure 6). Male swarming behavior that is a prerequisite for mating in many species of the Chironomidae was not observed in this species. Shortly after mating, the female lays her eggs on the surface of the water. The female inserts the tip of her abdomen beneath the water surface where she deposits the egg mass and dies soon afterwards. The egg stage lasts 36 to 48 hours.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Larval hatching is synchronous. The neonates are very active but remain inside the tubular gelatinous matrix for several hours, crawling from one end to the other (Figure 7). Eventually, they exit the gelatinous matrix from one end, or occasionally from the middle. The larvae at this stage of their development are free-swimming and vulnerable to predation. However, their translucent color and small size may afford them some protection until they can enter a shoot tip. Larvae can only survive for 48 hours without access to hydrilla so must find a host plant quickly. The larvae complete their development in 9 to 22 days.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Pupation occurs inside the hydrilla stem. The pupal stage lasts 24 to 48 hours. Adult emergence occurs after the sedentary pupa exits the stem by undulating its abdomen and slowly swimming to the surface, aided by an air bubble released inside the pupal skin.

Hosts

The hydrilla tip mining midge was discovered feeding on hydrilla in Crystal River in 1992. One requirement of biological control agents is that they are specific to the target weed. Field collections have so far indicated that Cricotopus lebetis is feeding specifically on hydrilla. However, further studies are needed to verify these findings. Laboratory testing revealed that Cricotopus lebetis was able to utilize several other species (Stratman et al. 2013a), with no difference in survival when compared to hydrilla, Cricotopus lebetis developed to the adult stage on three additional aquatic plants: Canadian waterweed Elodea canadensis Michx., Brazilian waterweed Egeria densa Planch, and Southern naiad Najas guadalupensis (Spreng.) Magnus (Stratman et al. 2013a). Interestingly, monoecious hydrilla was a better developmental host than dioecious hydrilla (Stratman et al. 2013a). In laboratory choice tests, larvae preferred the Florida natives Southern naiad and Canadian waterweed to hydrilla (Stratman et al. 2013a). In laboratory oviposition tests, females preferentially laid eggs on Canadian waterweed, compared to hydrilla, but there was no difference in oviposition preference between Southern naiad and hydrilla (Stratman et al. 2013a). The differences between the laboratory and field host specificity observed for Cricotopus lebetis can be explained by the fact that for most biological control agents, the laboratory host range is often broader than the field host range.

Damage

The hydrilla tip mining midge feeds on the growing tips of hydrilla plants during the larval stage. The neonate larvae swim to locate a hydrilla tip. Laboratory and field studies have shown that midge larvae are able to access tips at depths of 2.7 and 0.9 meters (Kariuki et al. 2019). Once inside the plant, the larvae mine and feed on the vascular tissues of the apical meristem of the hydrilla shoots (one larva per shoot tip). As they develop to maturity, their feeding activity creates a 1 to 2 cm tunnel inside the stems, which eventually kills the shoot tips and induces their abscission (Figure 8). The tunnels created by the developing larvae inside the shoot tips probably protect them from predators but also function as pupal cases.

Before pupating, the mature larva completely severs the tip of the shoot to create an escape route for the fully developed pupa and caps the opening of the tunnel with plant fibers excavated from the stem wall (Figure 9). Adult emergence occurs after the sedentary pupa exits the stem by repeatedly undulating its abdomen to break through the fibrous cap. The preparation of the pupal case by the last instar larva is what actually induces abscission of the shoot tip.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Credit: Jerry F. Butler, UF/IFAS

Importance as a Biological Control Agent

Cricotopus lebetis may have some potential as a biological control agent of hydrilla. The larvae of this herbivorous midge mine the meristematic tissues of the plant and, in the process, disrupt shoot growth. By severely damaging or killing the apical meristems, the developing larvae may prevent new stems from reaching the surface, thereby changing the plant's architecture. This type of damage is desirable for managing hydrilla because it would eliminate most of the adverse effects caused by the formation of the dense surface mats, such as changes in biodiversity, water chemistry, circulation, and temperature.

Efficacy studies have so far produced positive results. A field study conducted in Crystal River, FL, that assessed the hydrilla biomass and compared it to the number of tips damaged by Cricotopus lebetis found that with increasing larval midge density there was increasing numbers of tips damaged and a decrease in hydrilla biomass (Cuda et al. 2011). However, a laboratory study confirmed that one larva has the potential to damage two hydrilla tips (Baniszewski et al. 2020). A manipulative experiment conducted in tanks in a greenhouse also showed that Cricotopus lebetis was able to reduce the biomass of hydrilla by 99% in two months (Cuda et al. 2011). A laboratory study showed that C. lebetis maintained its efficacy when integrated with fungal pathogens Mycoleptodiscus terrestris (Mt) and the herbicide imazamox, and the insect could be incorporated into integrated hydrilla management strategies (Cuda et al. 2016).

However, except for Lake Rowell in Bradford Co., field populations of Cricotopus lebetis are relatively low. For example, a recent study of six lakes in Florida found the midge in only half of the lakes and at low abundance (Stratman et al. 2013b). Augmentation of the population by mass releases could increase the damage to hydrilla and reduce the vegetative biomass at the surface.

Studies to optimize mass rearing and release of Cricotopus lebetis have found that refrigeration of eggs for storage is not recommended (Baniszewski et al. 2015) and that eggs must be placed on hydrilla on or before the larvae hatch at 48 hours post-oviposition (Mitchell et al. 2017). Pupation and adult eclosion are highest when larvae are provided with at least one hydrilla tip per individual (Baniszewski et al. 2020). When releasing Cricotopus lebetis laboratory research suggests that it is better to release eggs than larvae (Stachowiak et al. 2021). The same study also suggests that predation may have a bigger impact on midge survival and potential for larval damage than competition (Stachowiak et al. 2021). It might be necessary to release more larvae to compensate for predation or consider protection from fish predation when making mass releases. For example, releasing larvae at night might reduce predation from day-feeding fish species.

Monitoring/Management

Cricotopus lebetis can be monitored in the field by collection of hydrilla and examining the tips for the presence of larvae or larval damage (Cuda et al. 2011). A more reliable method is collecting/holding hydrilla for several weeks in aerated trays within cages and collecting adults by aspirator. Cuda et al. (2002) described procedure for mass rearing C. lebetis under laboratory conditions, in which C. lebetis is reared within caged trays containing hydrilla stem tips submersed in aerated well water. Occasionally, the hydrilla stem tips sourced from the field are infested by the hydrilla leafcutter moth, Parapoynx diminutalis Snellen (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), a voracious defoliator of hydrilla and a competitor to C. lebetis. In these cases, the moth can be managed by applying a biorational pesticide Bacillus thuringiensis (subspecies kurstaki; Btk) into the trays at a rate of 0.2 or 2.0 mL Btk per 3.8 L of water (Baniszewski et al. 2016).

Management is not necessary for the hydrilla tip mining midge as it is not a pest in the US. However, it is susceptible to pesticides (Stratman et al. 2013c).

The authors would like to acknowledge funding provided by the USDA NIFA RAMP Grant 2010-02825 that helped pay for the revision of this article.

Selected References

Baniszewski J, Weeks ENI, Cuda JP. 2015. Impact of refrigeration on eggs of the hydrilla tip mining midge Cricotopus lebetis (Diptera: Chironomidae): larval hatch rate and subsequent development. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 53: 209–215.

Baniszewski J, Weeks ENI, Cuda JP. 2016. Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies kurstaki reduces competition by Parapoynx diminutalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) in colonies of the hydrilla biological control agent Cricotopus lebetis (Diptera: Chironomidae). Florida Entomologist 99: 644–647.

Baniszewski J, Miller N, Kariuki EM, Cuda JP, Weeks, ENI. 2020. Cricotopus lebetis Intraspecific competition and damage to hydrilla. Florida Entomologist 103: 32-37.

Cuda JP, Coon BR, Dao YM, Center TD. 2002. Biology and laboratory rearing of Cricotopus lebetis (Diptera: Chironomidae), a natural enemy of the aquatic weed hydrilla (Hydrocharitaceae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 95: 587–596.

Cuda JP, Coon BR, Dao YM, Center TD. 2011. Effect of an herbivorous stem-mining midge on the growth of hydrilla. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 49: 83–89.

Cuda JP, Shearer JF, Weeks ENI, Kariuki E, Baniszewski J, Giurcanu M. 2016. Compatibility of an insect, a fungus, and a herbicide for integrated pest management of dioecious hydrilla. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 54: 20–25.

Epler JH 1995. Identification manual for the larval Chironomidae (Diptera) of Florida, revised edition. Bureau of Surface Water Management, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Tallahassee, FL.

Epler JH, Cuda JP, Center TD. 2000. Redescription of Cricotopus lebetis (Diptera: Chironomidae), a potential biocontrol agent of the aquatic weed hydrilla (Hydrocharitaceae). Florida Entomologist 83: 172–180.

FWC. 2020. Annual report of activities conducted under the cooperative aquatic plant control program in Florida public waters for fiscal year 2019-2020. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Invasive Plant Management Section. https://myfwc.com/media/25501/annualreport19-20.pdf (Accessed 15 December 2021).

Haller WT. 1978. Hydrilla: a new and rapidly spreading aquatic plant problem. Circular S-245. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Kariuki EM, Cuda JP, Hight SD, Hix RM, Gettys LA, Gillett-Kaufman JL. 2019. Foraging depth of Cricotopus lebetis larvae. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 57: 69-78.

Langeland KA. 1990. Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata (L.F.) Royle), a continuing problem in Florida waters. Circular No. 884. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

MacRae IV, Winchester NN, Ring RA. 1990. Feeding activity and host preference of the milfoil midge, Cricotopus myriophylli Oliver (Diptera: Chironomidae). Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 28: 89–92.

Madeira PT, Van TK, Center TD. 1999. Integration of five Southeast Asian accessions into the world-wide phenetic relationships of Hydrilla verticillata as elucidated by random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. Aquatic Botany 63: 161–167.

Markham RH. 1986. Biological control agents of Hydrilla verticillata, final report on surveys in East Africa. Miscellaneous Paper A-86-4, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Waterways Experiment Station, Vicksburg, MS.

Michel A, Arias RS, Scheffler BE, Duke SO, Netherland MD, Dayan FE. 2004. Somatic mutation-mediated evolution of herbicide resistance in the nonindigenous invasive plant hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata). Molecular Ecology 13: 3229–3237.

Mitchell A, Berro A, Cuda JP, Weeks ENI. 2018. Effect of food deprivation on hydrilla tip mining midge survival and subsequent development. Florida Entomologist 101: 74-78.

Pinder LCV. 1986. Biology of freshwater Chironomidae. Annual Review of Entomology 31: 1–23.

Stachowiak C, Baniszewski J, Cuda, JP, St Mary C, Weeks ENI. 2021. Influence of competition and predation on survival of the hydrilla tip mining midge and its success as a potential augmentative biological control agent of hydrilla. Hydrobiologia 848: 581-591.

Stratman KN, Overholt WA, Cuda JP, Netherland MD, Wilson PC. 2013a. Host range and searching behavior of Cricotopus lebetis (Diptera: Chironomidae), a tip miner of Hydrilla verticillata. Biocontrol Science and Technology 23: 317–334.

Stratman KN, Overholt WA, Cuda JP, Netherland MD, Wilson PC. 2013b. The diversity of Chironomidae associated with hydrilla in Florida with special reference to Cricotopus lebetis (Diptera: Chironomidae). Florida Entomologist 96: 654–657.

Stratman KN, Wilson PC. Overholt WA, Cuda JP, Netherland MD, 2013c. Toxicity of fipronil to the midge, Cricotopus lebetis (Sublette). Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health-Part A-Current Issues 76: 716–722.