The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The cabbage palm caterpillar, Litoprosopus futilis (Grote & Robinson), sometimes referred to as the cabbage palm worm, is the larva of an owlet moth. The author has collected larvae feeding on the inflorescence of cabbage palmetto, Sabal palmetto. Severe infestations of this caterpillar can seriously affect the production of palmetto honey. These caterpillars may also cause problems by invading structures.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Synonymy

The larva was initially described by S.E. Crumb from a US National Museum specimen collected on saw palmetto, Serenoa repens Astoria, Florida, by H.G. Dyar. In 1868, the adult was described by A.R. Grote and C.T. Robinson as Dyops futilis.

Distribution

The cabbage palm caterpillar is distributed throughout much of Florida. There are verified records of this species in coastal South Carolina (Opler et al. 2010) and Texas (Burke et al. 1994). This species probably exists in other areas of the southeastern US where its host occurs.

Description

Adult

The adult moth is usually fawn-colored and has a wing expanse of about 2 inches. The body is the same color as the forewings. However, several color variations exist (Patterson 2010). A dark eyespot about 3/16 inch in diameter is found on each hind wing. Within each spot are two approximately parallel white dashes.

Credit: Doug Caldwell, Collier County Cooperative Extension Service, University of Florida

Larva

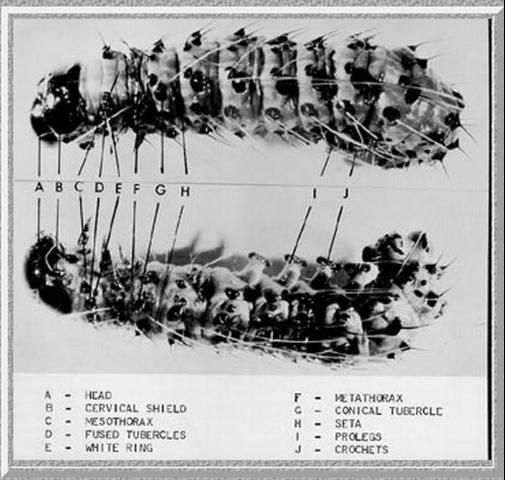

The mature larva is about 1.5 inches in length. The larva is covered with very small black spines, which are not visible to the naked eye. The body appears pinkish in color, while the head and cervical shield are shiny black. When examined under low magnification (10x), the larva is taffy-colored with pinkish stripes extending from the cervical shield to the last abdominal segments.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

The larva have extremely long, strong, white primary setae that arise from shiny black conical tubercles. Setigerous tubercles 1a and 1b (tubercles occurring on the scutellum or legs, each bearing a spine or bristle on its top.) are fused on the mesothorax and metathorax. The black bases of setae 1a and 1b on the mesothorax are ringed with white, and this is a very useful diagnostic character of the larva. The spiracles are entirely black. Prolegs with crochets in a mesoseries are present on abdominal segments three, four, five, and six. The larva becomes very pink just before pupating.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Pupa

A tough cocoon protects the dark reddish brown pupa.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Hosts

The FDACS-Division of Plant Industry has recorded the cabbage palm caterpillar on numerous plants. It is the opinion of the author that all host records on plants other than palm are erroneous. Although DPI plant specialists have collected larvae on various plants, it is doubtful that these represent valid host records. All records for Litoprosopus futilis feeding on Sabal spp. are valid.

Field Observations

The following account is from observations made by R.W. Massie, Geneva, Florida: "The palm caterpillar can usually be found on the cabbage palm at the time the embryonic bloom is in the small green bud stage. Tiny larvae may be found deep in the developing bloom spikes. The larvae sometimes gather in the thousands on the immature buds, entirely denuding the palms of all trace of bloom as they feed. The fully mature caterpillar may then drop to the ground on a silken thread and crawl to a protected pupation site or crawl down the trunk and beneath the base of a dead frond to construct a cocoon from dry palm fibers."

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Economic Importance

High populations of the cabbage palm caterpillar feeding on flowers can drastically reduce the amount of palmetto honey produced. As this type of honey is extensively collected and marketed, especially in Florida, this can result in economic hardship for beekeepers as well as affecting the consumer by a sharp increase in honey prices.

During periods of high infestation, the mature caterpillars may invade structures, including homes, seeking pupation sites. The wandering larvae release a reddish-brown fluid, which stains siding and other areas they crawl on (Wagner et al. 2009). The caterpillars incorporate any available fabric, such as draperies, rugs, stuffed furniture, bedding, and clothing, when making their cocoons, which may damage these items. In 1961, an outbreak in Miami, Florida, caused serious economic loss to fiberglass cloth used by the boat building industry.

Management

Protecting palm flowers from the cabbage palm caterpillar is difficult. Properly labeled insecticides or Bacillus thuringeinsis (Bt) formulations could be applied to palms when caterpillars are present, but in order to be effective such an endeavor would require careful monitoring to properly time the application, especially to avoid impacting beneficial insects, such as foraging bees.

Because cabbage palm caterpillars will enter structures to pupate, it is important to find their entry points and block them. However, not all materials will stop these caterpillars, as they can chew through fiberglass window screen and have been observed chewing on drywall. Cabbage palm caterpillar adults are strongly attracted to lights and during outbreak years, moths can enter structures and be a nuisance. Again, find and block entry points with caulk or screen.

Biological control may be important in the reduction of cabbage palm caterpillar populations, but this method of management has not been explored. Parasitoids or pathogens may be more useful than predators, primarily because the larvae produce an oral regurgitant when disturbed, which appears to be a deterrent against some predators (Smedley 1993).

Selected References

Burke HR, Jackman JA, Rose M. 1994. Insects associated with woody ornamental plants in Texas. Texas Agricultural Extension Service and Texas Agricultural Experiment Station. 168 pp.

Crumb SE. 1956. The larvae of the Phalaenidae, USDA Technical Bulletin 1135: 327.

Kimball CP. 1965. Lepidoptera of Florida. Arthropods of Florida, Florida Department of Agriculture 1: 135.

Opler PA, Lotts K, Naberhaus T. (2010). Palmetto borer moth. Butterflies and Moths of North America. (27 April 2016)

Patterson R. (January 2010). Litoprosopus futilis - (Grote & Robinson, 1868). North American Moth Photographers Group. http://mothphotographersgroup.msstate.edu/species.php?hodges=8556 (27 April 2016)

Smedley SR, Ehrhardt E, Eisner T. 1993. Defensive regurgitation by a noctuid moth larva (Litoprosopus futilis). Psyche 100: 209–221.