The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Throughout time, lice, particularly head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis De Geer), have been a common reoccurring problem, especially in schools. Millions of American school children may encounter head lice during the school year. Head louse infestations throughout the United States affect people on all social and economic levels.

Before World War II, head lice were fairly common in the United States, body and crab lice much less so. After World War II and the emergence of DDT as a louse control agent, outbreaks of lice were much less common. Now lice again are intruding into the environment of the average American. Lice or their eggs are easily transmitted from person to person on shared hats, coats, scarves, combs, brushes, towels, bedding, upholstered seats in public places, and by personal contact. Sharing these articles is common among young school-age children. As a result, head lice infestations are most prevalent among children, whereas body and pubic (crab) lice are more frequently encountered among young adults and middle-aged persons. When someone becomes infested with lice, it is likely that the entire family will become infested.

Human louse infestation, called pediculosis, can spread rapidly and may reach epidemic proportions if left unchecked. In a group of people, such factors as age, race (for example, African Americans are rarely infested with head lice (Slonka et al. 1975)), sex, crowding at home, family size, and method of closeting clothes influence the course and distribution of the infestation. The length of the hair does not appear to be a significant factor.

It is generally assumed that body lice evolved from head lice after mankind began wearing clothes.

Identification

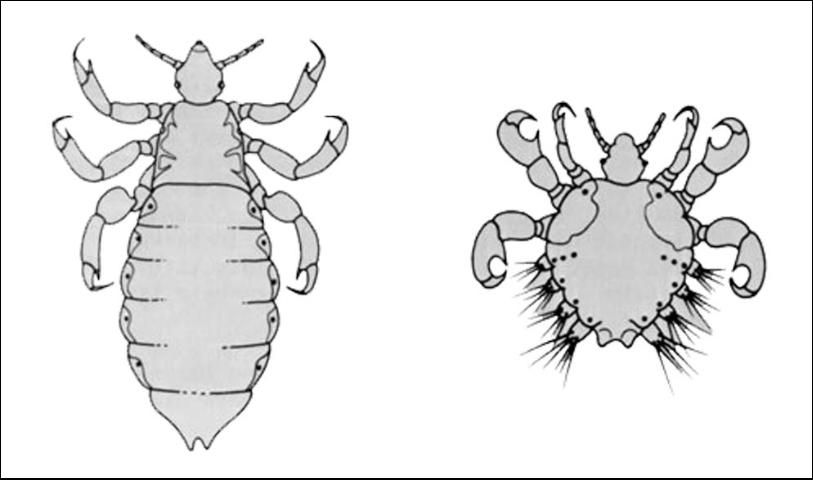

Three types of lice infest humans: the body louse, Pediculus humanus humanus Linnaeus, also known as Pediculus humanus corporis; the head louse Pediculus humanus capitis De Geer; and the crab louse (or pubic louse), Pthirus pubis (Linnaeus).

Head lice and body lice are morphologically indistinguishable, although head lice are smaller than body lice. Head lice and pubic lice are highly dependent upon human body warmth and will die if separated from their host for 24 hours. Body lice are hardier since they live on clothing and can survive if separated from human contact for up to a week without feeding.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: UF/IFAS

Biology

Lice have simple or gradual metamorphosis. The immatures and adults look similar, except for size. Lice do not have wings or powerful jumping legs, so they move about by clinging to hairs with their claw-like legs. Head lice prefer to live on the hair of the head although they have been known to wander to other parts of the body. Head lice do not normally live within rugs, carpet, or school buses. Body lice live in the seams of clothing, generally where it touches the skin, and only contact the body to feed, usually holding on to the clothing while they do this. However, sometimes they will move to the body itself.

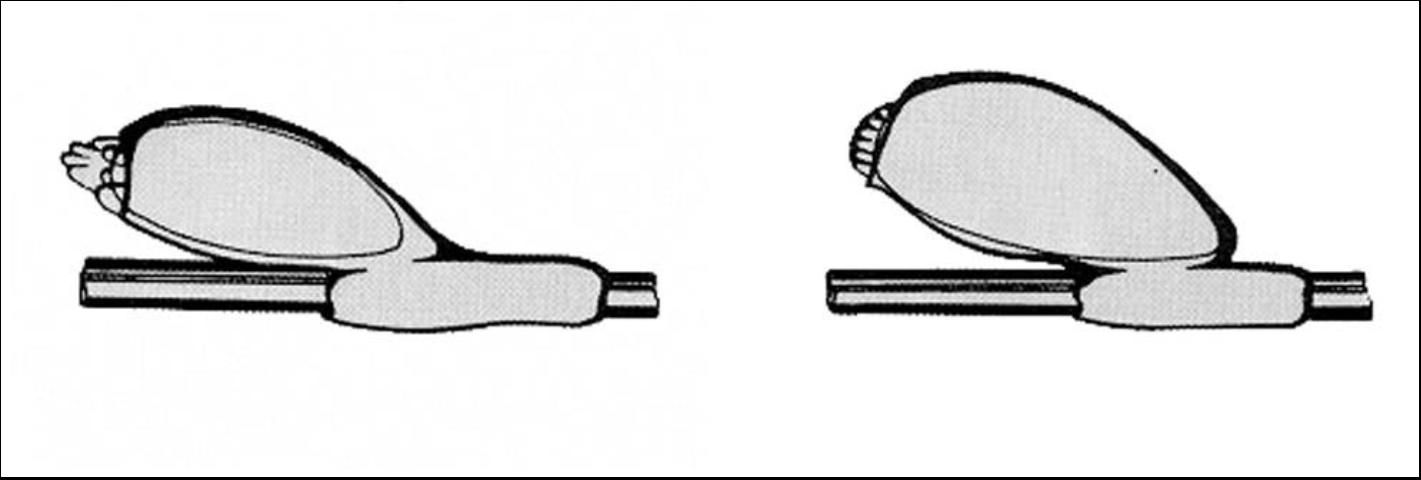

The eggs of lice are called nits. They are oval white cylinders (1/16 inch long). The eggs of head lice are usually glued to hairs of the head near the scalp. The favorite areas for females to glue their eggs are near the ears and back of the head. The eggs of body lice are laid on clothing fibers and occasionally on human body hairs.

Under normal conditions the eggs will hatch in seven to 11 days. The young lice which escape from the egg must feed within 24 hours or they will die. Newly hatched lice will periodically take blood meals and molt three times before becoming sexually mature adults. Normally a young louse will mature in 10 to 12 days to an adult (1/8 inch in length). Adults range in color from white to brown to dark gray.

Female lice lay six to seven eggs (nits) per day and may lay a total of 50 to 100 eggs during their life which may last up to 40 days. Adults can only survive one to two days without a blood meal. The nymphs and adults all have piercing-sucking mouthparts which pierce the skin for a blood meal. The reaction of humans to louse bites can vary considerably. Persons previously unexposed to lice experience little irritation from their first bite. After a short time, individuals may become sensitized to the bites and may react with a general allergic reaction including reddening of the skin, itching, and overall inflammation.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Clay Scherer, UF/IFAS

Both the immature or nymphal forms and adult lice feed on human blood. To feed, the louse bites through the skin and injects saliva which prevents blood from clotting; it then sucks blood into its digestive tract. Bloodsucking may continue for a long period if the louse is not disturbed. While feeding, lice may excrete dark red feces onto the skin.

Symptoms of Louse Infestation

Head lice should be suspected when there is intense itching and scratching of the scalp and the back of the neck or when there is a known infestation in the community. Close examination of the scalp will reveal small, whitish or dark eggs (nits) firmly attached to hair shafts, especially at the nape of the neck and above the ears. Inspection may reveal active lice and many itchy, red marks resulting from irritation caused by the saliva of the louse. Although dandruff may resemble eggs, it can be removed easily from hair, whereas louse eggs are attached firmly to the hair with cement secreted by the louse and cannot be removed easily by pulling. When an infestation becomes known, it is advisable to examine all members of the family, especially other children, and others who have been in contact with the infested person within recent weeks to be sure that they have not become infested.

Credit: Clay Scherer, UF/IFAS

Body lice are found in tight-fitting sites or seams of clothing, usually close to the skin. Only in heavy infestations will body lice be seen on other layers of clothing. Infestations usually occur where humans continuously wear several layers of clothing due to inadequate heating or during periods of war or natural disasters. Louse infestations may also occur in poorly managed nursing homes, and among the poor and homeless. The main reasons for these infestations are the failure to change garments and/or inadequate laundering.

Disease Transmission

The body louse is the vector of three human diseases—epidemic or louse-borne typhus, caused by Rickettsia prowazeki de Rocha-Lima; trench fever, caused by Rochalimaea quintana (Schmincke) Krieg (long known as Rickettsia quintana); and louse-borne relapsing fever, caused by Borrellia recurrentis (Lebert) Bergy et al. (PAHO 1973). These diseases are not presently being reported from the United States, but their introduction at some future time is not impossible if body louse infestations should become sufficiently prevalent. Although head lice have been experimentally infected with Rickettsia prowazeki, neither head lice nor pubic lice have been implicated directly in active disease transmission (Roy and Brown 1954). Although body lice may pose the most serious health threat in many countries, head lice appear to be the greatest nuisance, particularly among school children in highly developed countries where their presence is considered intolerable.

Management

The biggest problem in controlling head lice infestations is convincing parents, teachers and even school administrators that head lice infestations are not caused by filthy conditions. For example, one school principal denied the existence of a head lice infestation in his school, even though the wife of a University of Florida graduate student, who was a teacher at that school, confirmed that the problem existed. The principal's denial of the problem, and his refusal for our staff to cooperate with his school nurse, prevented us from controlling the infestation and preventing its recurrence. In addition, lack of knowledge of the biology and ecology of the head louse resulted in the school administrator calling in the school district-contracted, pest control company and demanding that its personnel spray the rugs for control of the head louse infestation. Since head lice occur only on the bodies of children, the pest control company was powerless to do anything to control the infestation. But this did not stop the principal from threatening to cancel the contract. Education of all levels of society on the biology and control of head and body lice is essential for controlling frequent reoccurring infestations.

For more information see: Downloadable computer presentation on head lice (http://schoolipm.ifas.ufl.edu/pres_pst.htm).

Adequate sanitation, including frequent changes of clothing, and laundering clothing and bedding in hot water, or dry cleaning, ordinarily is enough to prevent permanent infestations of body lice, since they remain on the clothing and are killed by the cleaning process. However, head lice and crab lice cannot be controlled in this way. Once a few lice are picked up they remain in the hair and are not killed by ordinary shampoos or bathing. Insecticides are therefore necessary to control these species, and to control body lice also when war, catastrophe, economic conditions, or traditional customs prevent adequate laundering.

Chemicals are available as prescription or non-prescription drugs to control lice. Over-the-counter products which should be effective include those containing permethrin or pyrethrins (pyrethrum extract) as active ingredients. These drugs are available as creams, lotions, or shampoos. Shampoos are preferred for control of head lice. The application of these insecticidal drugs will kill nymphs, adults, and some eggs. Eggs killed by treatment as well as unaffected eggs may remain attached to hair shafts and should be removed as soon as possible. To remove these eggs it may be necessary to do some "nit-picking" utilizing a special fine-toothed lice comb. Combs and other tools used to remove lice should be soaked in a lice killing solution such as rubbing alcohol after use.

Use of lice sprays to treat objects such as toys, furniture, carpet etc. is not recommended because lice cannot live off the host longer than a couple of days. The same holds true for classrooms. Use of these products is considered ineffective and unnecessary.

Insecticidal shampoos are available as over-the-counter preparations at drugstores. Carefully read the label as some shampoos should be used only once. Prescription products containing the active ingredients malathion and lindane are not recommended for use on children or adults. These products have had reported side effects. In addition, never use gasoline or kerosene or other flammable liquids as home remedies. Children have been killed or severely burned as the result of accidents that occurred while using these flammable liquids.

Nit combs, with much smaller spaces between the tines, are also commercially available for regular use in the control of head lice.

For more management information see: Insect Management Guide for Body Lice and Pubic Lice (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IG084).

Selected References

Anonymous. 1975 September. A handbook of guidelines for dealing with Pediculosis capitis (head lice). Division Elementary and Secondary Education, Dade County Public Schools (Florida), in cooperation with Dade County Dept. Public Health. 10 p.

Anonymous. 1975. Basic information about human lice. Pharmecs Division, Pfizer Inc., New York, New York. 12 p.

Borror DJ, Triplehorn CA, Johnson NF. 1989. An Introduction to the Study of Insects. 6th Ed. Harcourt Brace, New York. 875 p.

Bosik JJ, et al. 1997. Common Names of Insects and Related Organisms 1997. Entomological Society of America, Lanham, MD.

Fasulo TR. (2002). Bloodsucking Insects. . University of Florida/IFAS. CD-ROM. SW 151.

Fasulo TR, Kern W, Koehler PG, Short DE. (2005). Pests In and Around the Home. Version 2.0. University of Florida/IFAS. CD-ROM. SW 126.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). 1973. The Control of Lice and Louse-borne Diseases. Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Control of Lice and Louse-borne Diseases, Washington, D.C., 4-6 December 1972. World Health Organization, Washington, D.C. Scientific Publ. 263. 311 p.

Roy DN, Brown AWA. 1954. Entomology (Medical & Veterinary) including Insecticides & Insect & Rat Control. 2nd ed. Excelsior Press, Calcutta, India. 413 p.

Scherer C, Koehler PG. (July 1999). Biology and Control of Head Lice. School Integrated Pest Management. (21 November 2013)

Slonka GF, McKinley TW, et al. 1975 April. Controlling head lice. (unnumbered publication) United States Dept. Health, Education and Welfare, Public Health Service, Center for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia. 16 p.

Snetsinger RJ. 1990. In Handbook of Pest Control. 7th Edition. Story K, Moreland D (eds.). Franzak & Foster Co., Cleveland, OH. pp 583–596.