The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

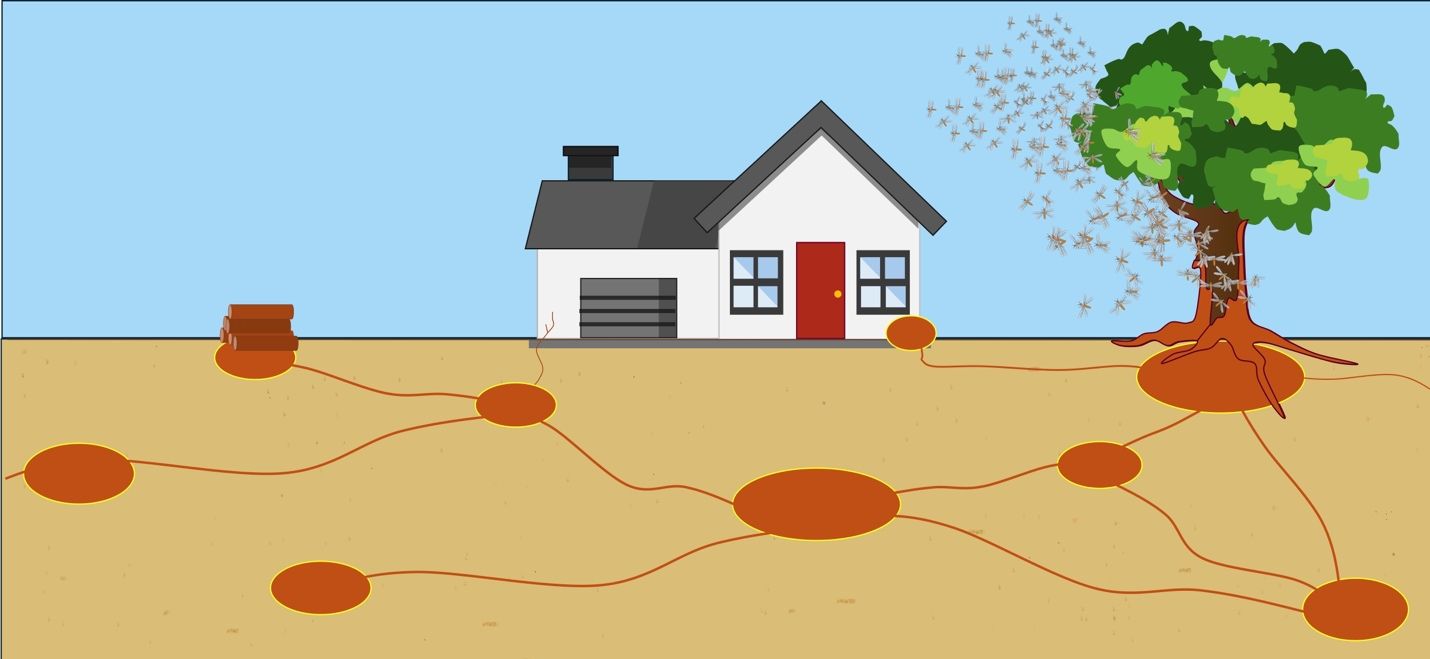

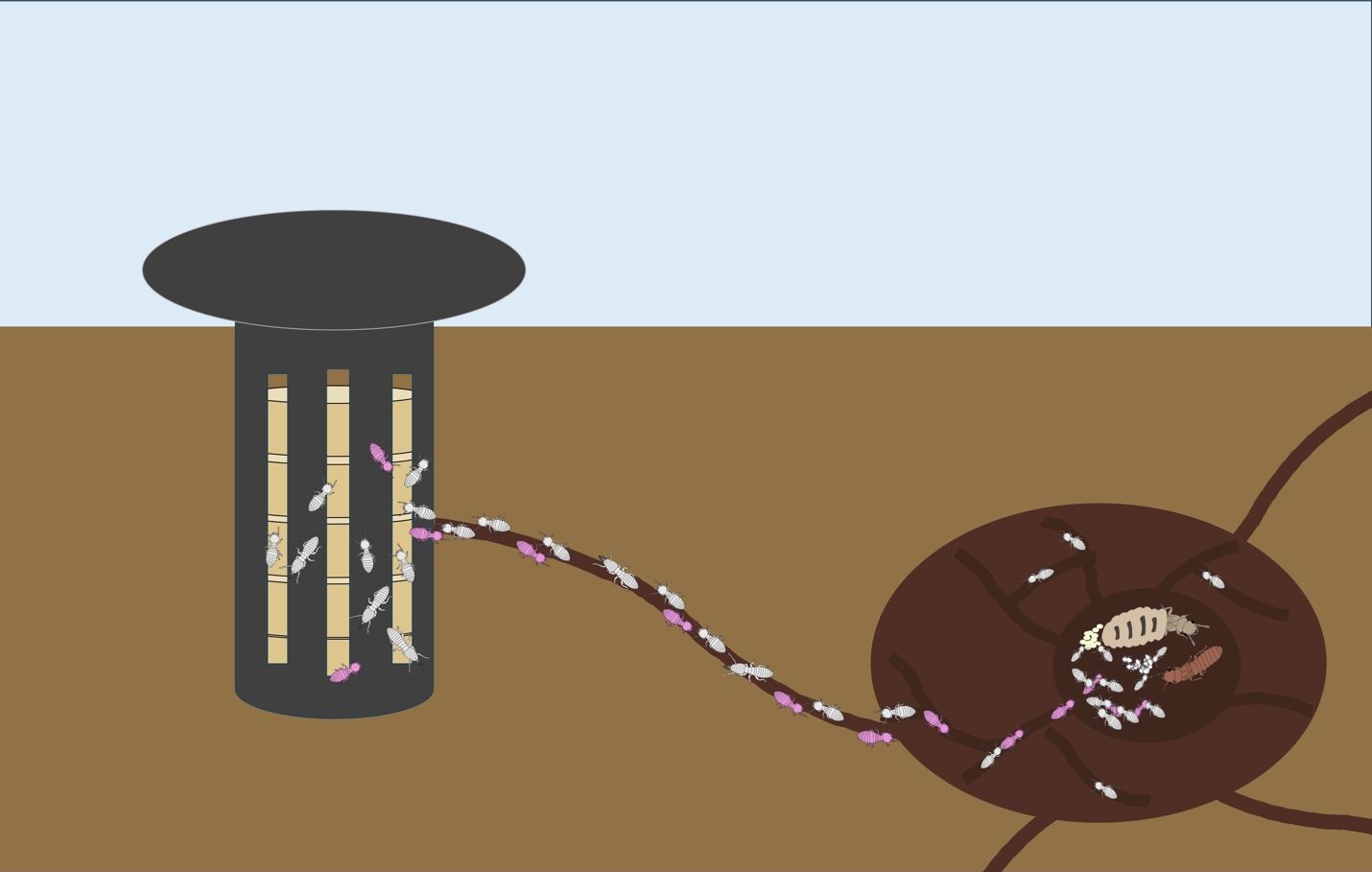

Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki, commonly known as the Formosan subterranean termite, is an invasive termite species, found in subtropical and temperate regions. Due to their large population size and foraging distance (Figure 1), a Formosan subterranean termite colony can cause significant structural damage. This species is considered a major pest in areas where it is established.

Credit: Original graphic by Nan-Yao Su, UF/IFAS; modified by Johnalyn Gordon, UF/IFAS

Distribution

Coptotermes formosanus is endemic to Taiwan and southern China (Scheffrahn 2023). In Hawaii, it was first described in the late 1800s (Su and Tamashiro 1987) and, in the continental United States, introductions to New Orleans, Louisiana (Spink 1967), Charleston, South Carolina (Chambers et al. 1988), and Hallandale, Florida (Scheffrahn et al. 1988) are among the first recorded. It is likely that the spread of Coptotermes formosanus is the result of human transport, including maritime transport and the shipment of goods across the world (Scheffrahn 2023).

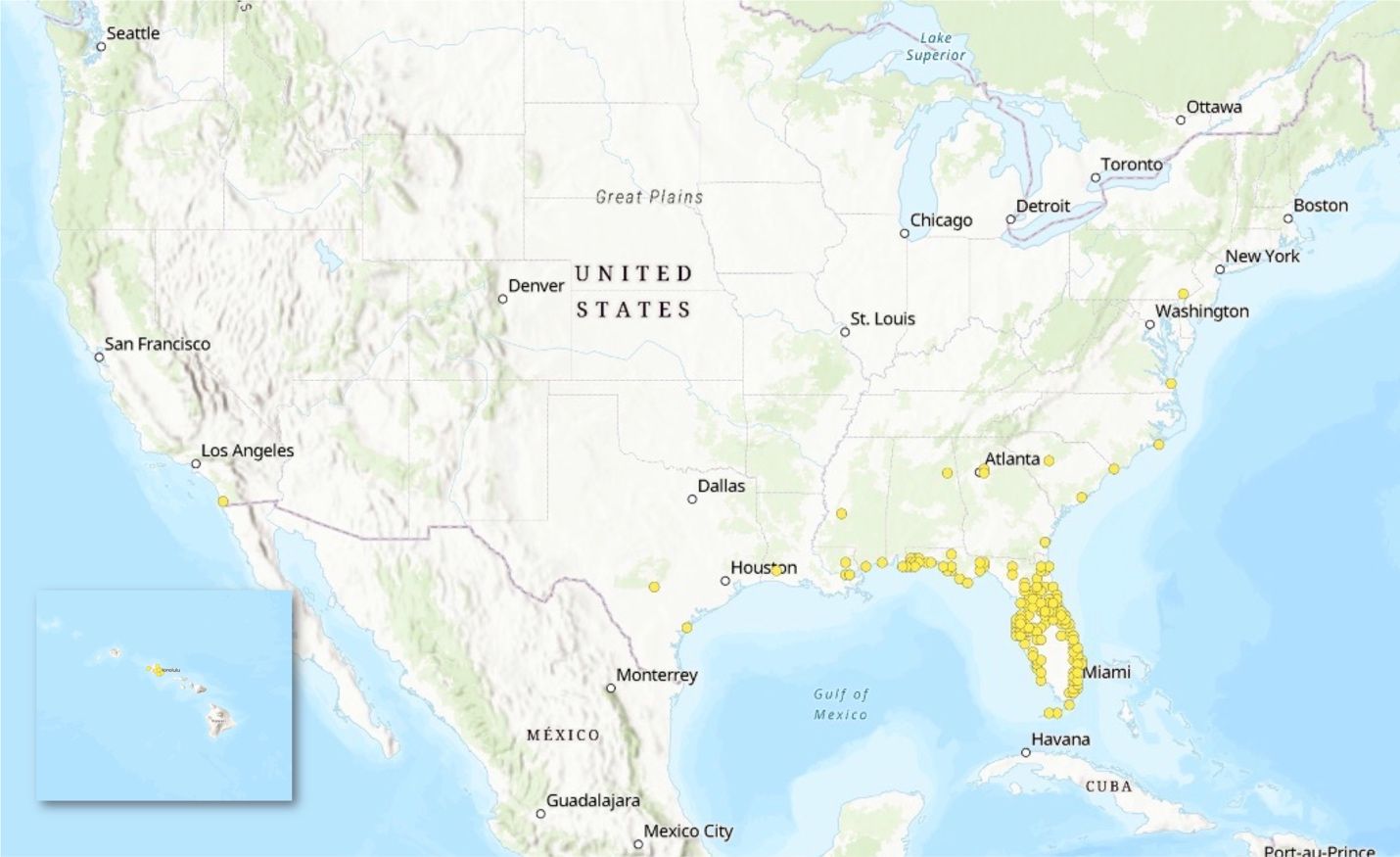

To date, the Formosan subterranean termite can be found in Hawaii and throughout southeastern regions of the continental United States (Blumenfeld et al. 2021; Vargo et al. 2006). It has also been found north along the Atlantic coast up to Virginia (Hottel 2022), with reports as far inland as Tennessee (Su 2003) (Figure 2).

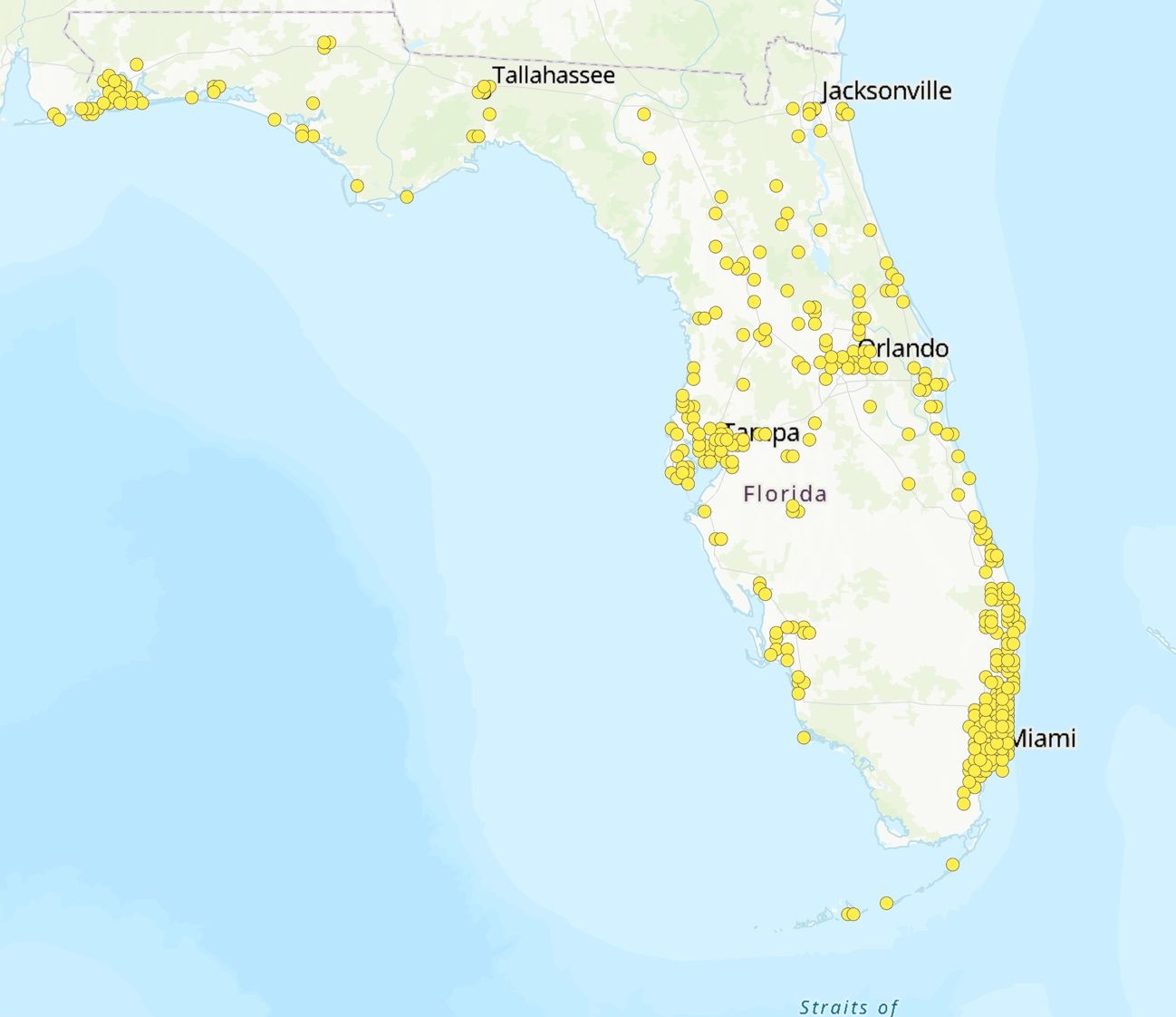

On the US West Coast, Coptotermes formosanus has been found in southern California (Atkinson et al. 1993; Tseng et al. 2022) (Figure 2). In Florida, the Formosan subterranean termite is distributed throughout the state, primarily in urban areas with high population density (Figure 3).

Credit: Locality data are from the University of Florida Termite Collection

Formosan subterranean termite colonies are usually located underground, with a central nest containing the reproductive (royal) pair (queen and king) and a large portion of the colony, including the eggs and larvae. Satellite nests of workers and soldiers are established in close proximity to food resources, or within trees.

Formosan subterranean termite colonies can forage tremendous distances underground in search of food and have been found to forage long distances of up to 100 m in the field (King and Spink 1969; Su and Scheffrahn 1988) and 300 m (328 ft) in laboratory studies (Su et al. 2017). Only workers are able to digest cellulose and, after feeding on wood, they are aided in the digestion of the cellulose by protozoan endosymbionts within their gut. Workers then pass nutrients to other members of the colony (reproductives, soldiers, larvae) through trophallaxis (food exchange). As workers are the only termite caste feeding on wood, they are the caste responsible for causing damage.

Credit: Locality data are from the University of Florida Termite Collection

Description

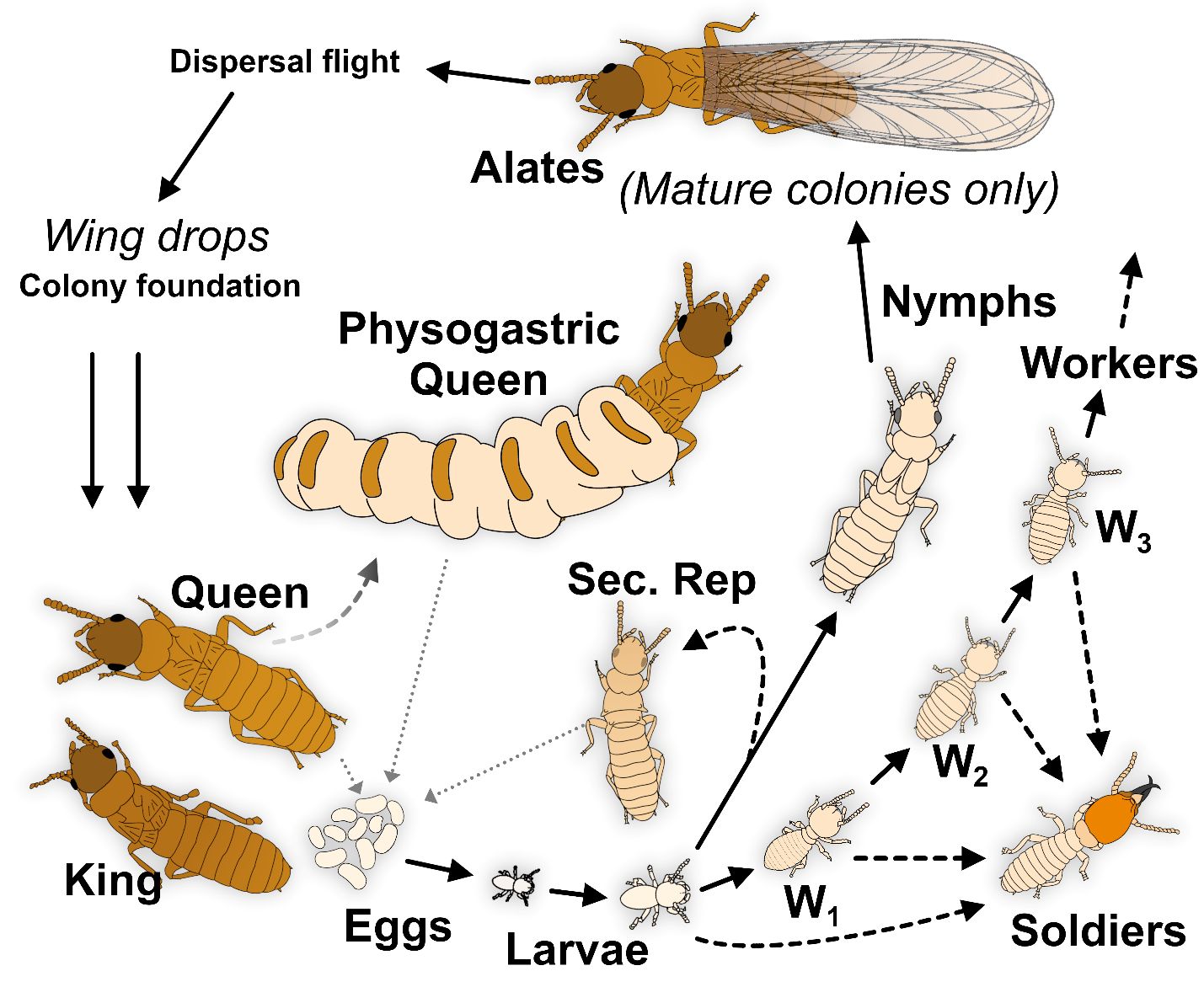

Members of a termite colony fall under three major divisions, known as castes: workers, soldiers, and reproductives (Figure 4). Termites can be identified to the species level using morphological characters of soldiers and alates (ENY-2079/IN1360). Each individual starts out as an egg. Upon hatching, the larva goes through two larval instars before molting into either a soldier or a worker, two sterile castes. (Chouvenc 2023). Depending on colony maturity, early instar larvae have the ability to molt into nymphs, and subsequently into reproductives. While each caste varies widely in appearance, all termites have moniliform (bead-like) antennae, a key trait present in all termites.

Credit: Modified from Chouvenc (2023), by Thomas Chouvenc, UF/IFAS

Workers are the most abundant caste within a subterranean termite colony. They are responsible for the majority of tasks within the colony, including foraging (finding and feeding on wood). Coptotermes formosanus workers are ~3–4 mm (~0.12–0.16 in) in length, wingless, and white to cream in color (Figure 5). They continue to molt throughout their lives. This aspect of their biology is key to the efficacy of termite baits for control (see “Management”).

Credit: Thomas Chouvenc, UF/IFAS

Formosan subterranean termite soldiers are slightly larger than workers (~4–5 mm [~0.16–0.2 in]), and have a white body, a brownish-orange teardrop-shaped head capsule, dark curved mandibles, and do not possess wings (Figure 5). Coptotermes formosanus soldiers also have an enlarged opening on the front of the head, called a fontanelle. When threatened, they exude a white glue-like substance through their fontanelle (Figure 6). This behavior and defensive secretion differentiate Coptotermes soldiers from native subterranean termites (Reticulitermes sp.). Additionally, Formosan subterranean termite colonies contain a greater percentage of soldiers (10%–15% of the colony) in contrast to native Reticulitermes colonies (EENY212/IN369), in which soldiers typically make up 1%–2% of the colony population. This high soldier proportion and ready use of defensive secretions, along with high levels of foraging, lead to Formosan subterranean termites often being described as an “aggressive” termite species.

Credit: Thomas Chouvenc, UF/IFAS

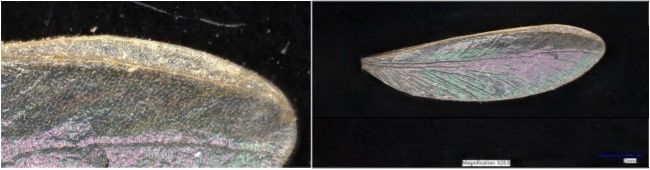

The only caste to have wings, alates, are larger than workers or soldiers at ~12–15 mm (0.5–0.6 in) in length. They also have an overall darker body color compared with other members of the colony. Coptotermes formosanus alates are typically an orange or light amber-brown in color (Figure 7). Subterranean termite alates have four equal-sized wings with two darkened (sclerotized) veins along the top margin of the wing, with no cross-veins between (Figure 8). Both the bodies and wings (including wing membranes) of Formosan subterranean termite alates are covered in small hairs (Figures 7 and 8).

Credit: Thomas Chouvenc, UF/IFAS (left); Johnalyn Gordon, UF/IFAS (right)

Credit: Johnalyn Gordon, UF/IFAS

Coptotermes formosanus, like other subterranean termite species, feed on the less dense “spring wood,” leaving characteristic feeding patterns that follow the wood grain. Coptotermes formosanus (along with its congener, Coptotermes gestroi, EENY128/IN285) will often bring soil into the feeding galleries (Figure 9) and fill voids with carton nest, a blend of soil, wood pulp, termite saliva, and termite feces (Figure 10). To protect against predators and moisture loss, subterranean termite foragers will often build mud tubes (Figure 11), composed of soil and saliva as they seek out new food sources or travel back and forth between food sources and the colony. While mud tubes and damage can be indicative of subterranean termite activity, the presence of live termites is needed to confirm an active infestation (Oi 2023).

Credit: Johnalyn Gordon, UF/IFAS (left and middle); Aaron Mullins, UF/IFAS (right)

Credit: Johnalyn Gordon, UF/IFAS

Credit: Aaron Mullins, UF/IFAS

In addition to infesting structures, Coptotermes formosanus also infest live trees, typically feeding on the dead xylem at the center and hollowing out the tree (Figure 12). While this does not directly impact the health of the tree, it can weaken it structurally and make it more susceptible to collapse, especially in high winds. Trees surrounding a structure should be inspected regularly for termite activity, both as an early detection measure for termites before they infest the structure and to identify weakened trees before property damage from falling trees can occur.

Credit: Thomas Chouvenc, UF/IFAS

Life Cycle

Once mature, colonies will produce alates that leave their respective colonies on dispersal flights (“swarms”). Time of day and time of year that dispersal flights occur varies by species and location. In Florida, Coptotermes formosanus typically swarms between early April and late June, shortly after sunset, with peak swarming activity in May. These dispersal flights can contain upwards of tens of thousands of individuals. In cases of structural infestation, these swarms can occur indoors.

Following the successful pairing of a single male and female alate, they will shed their wings (hereafter termed “dealates” [Figure 13]) and follow in a tandem-running behavior. The female dealate searches for a crack or crevice with sufficient moisture to start the colony as the male dealate follows closely behind. Alates are also attracted to lights, which can attract them to structures or boats (Scheffrahn 2023). If the dealate pair are successful, Formosan subterranean termite colonies reach maturity in 5–8 years (Chouvenc 2023), at which point the colony will begin to produce the next generation of alates.

Credit: Johnalyn Gordon, UF/IFAS

Economic Importance

The Formosan subterranean termite is considered one of the most damaging pest termite species in the world and has consistently been listed as one of the 100 worst invasive species in the world (ISSG 2011; Lowe et al. 2000). The annual costs associated with subterranean termites in the United States, including Coptotermes formosanus, has been estimated at over $30 billion (Rust and Su 2012), and the annual economic impact of Coptotermes formosanus alone in the United States is likely >$4 billion (Su and Lee 2023).

Management

Management for the Formosan subterranean termite falls into two categories: preventative, new-construction treatments, also known as “pre-treatments,” and post-construction treatments, also known as remedial or curative treatments following the identification of an infestation. Any products making structural protection claims must meet the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) performance standards (OPPTS 810.3600 and OPPTS 810.3800). Additionally, the state of Florida also requires performance standards be met, as detailed in the Florida Administrative Code 5E-2.0311, Performance Standards and Acceptable Test Conditions for Preventive Termite Treatments for New Construction (FDACS 2023). In areas with high density of Formosan subterranean termites, frequent inspection and/or preventative treatments are critical for catching infestations early and preventing structural damage. Control of Formosan subterranean termites requires professional pest control services and over-the-counter products are unlikely to be effective (Oi 2022).

Preventative treatments (further outlined in ENY-2044/IN1277) for subterranean termite damage include moisture reduction within and around the structure, thereby eliminating conductive conditions for subterranean termites, as well as the use of pressure-treated wood, which has been impregnated with preservatives such as creosote (outdoor uses only, such as railroad ties and utility poles), borate, and various copper-based products using positive vacuum pressure. While the use of treated wood can provide protection against fungal decay and termite damage for wood that is in contact with the soil, especially when used in conjunction with other control methods, there is no guarantee of permanent protection from termite damage with wood treatment. Further, it can be challenging to implement the use of treated wood post-construction.

Liquid termiticides are utilized for both pre-construction treatment and for post-construction population control. For pre-treatments, liquid termiticides are applied to the soil underneath the foundation before it is poured, as well as to soil around the perimeter of the foundation (Hu 2011). Post-construction, non-repellent liquid termiticides are often applied for structural protection through “trenching” and treating the soil around the perimeter of the structure or drilling and injecting through the foundation or slab. Liquid and foam termiticide formulations can also be injected into cracks, crevices, or wall voids (Lee and Neoh 2023; Potter 2011). Non-repellent liquid termiticides, when applied at correct concentrations, as directed by the pesticide label, can provide control in close proximity to the treated structure (Hu 2005; Hu 2011; Potter and Hillery 2002). If colony elimination is the goal of the treatment strategy, one challenge with non-repellent liquid termiticides is their dose-dependent lethal time (Lee and Neoh 2023; Yeoh and Lee 2007), as mortality can occur too quickly, resulting in termites dying adjacent to treatment and before being able to transfer the insecticide to other members of the colony (Chouvenc 2024). Dead termites are repellent, and live foraging workers may be repelled from entering the treated zone for a period of time, not by the termiticide, but by the accumulation of dead termites (Chouvenc 2024; Su 2005). When properly implemented, non-repellent liquid termiticides can provide protection for a structure, but it is unlikely that termite colony activity in surrounding area will be eliminated.

Termite bait stations can be used as both new construction and remedial treatments. They contain chitin-synthesis inhibitors (CSIs) as their active ingredient and are placed in-ground, around the exterior of a structure. CSIs target termite workers, the caste responsible for foraging and causing structural damage. Since subterranean termite workers molt throughout their life, once the bait-fed worker attempts to molt, the chitin-synthesis inhibitor disrupts the molting process, causing the termite to die several weeks after being exposed to the bait. Once all workers in the colony are dead, the remaining larvae, soldiers, and reproductives starve to death, eliminating the colony (Gordon et al. 2022). CSI baits are slow-acting due to their dose-independent lethal time, killing termite workers long after they have transferred the toxicant to other members of the colony and ensuring that the bait is transferred within the colony through trophallaxis (Figure 14). While they can provide structural protection by eliminating subterranean termite colonies in the surrounding area, a challenge with termite baits is the time needed for foragers to encounter the in-ground bait stations, as well as the time needed for all termite workers within the colony to molt (and subsequently die), which is approximately 3 months (Chouvenc and Su 2017). Above-ground bait stations can mediate the first challenge, as they can be placed directly on foraging sites in both structures and trees (Figure 15).

Credit: Johnalyn Gordon and Thomas Chouvenc, UF/IFAS

Credit: Thomas Chouvenc, UF/IFAS

Resources

The termite research team at the UF/IFAS FLREC provides additional resources at https://flrec.ifas.ufl.edu/termites-in-florida/, including a current termite distribution map and information on how to send samples for identification. Each sample provides a data point that helps to improve the distribution map and our knowledge of termites in Florida.

Selected References

Atkinson, T., Rust, M., Smith, J., 1993. The Formosan subterranean termite, Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) established in California. Pan-Pacific Entomologist 69(1): 111–113. https://ia600703.us.archive.org/21/items/biostor-244740/biostor-244740.pdf

Blumenfeld, A.J., Eyer, P.-A., Husseneder, C., Mo, J., Johnson, L.N., Wang, C., Kenneth Grace, J., Chouvenc, T., Wang, S., Vargo, E.L., 2021. Bridgehead effect and multiple introductions shape the global invasion history of a termite. Communications Biology 4, 196. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-01725-x

Chambers, D., Zungoli, P., Hill, H., Jr, 1988. Distribution and habitats of the Formosan subterranean termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) in South Carolina. Journal of Economic Entomology 81, 1611–1619. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/81.6.1611

Chouvenc, T., 2023. A primer to termite biology: Coptotermes colony life cycle, development, and demographics. Biology and Management of the Formosan Subterranean Termite and Related Species. CABI GB, pp. 40–81. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781800621596.0004

Chouvenc, T., 2024. Death zone minimizes the impact of fipronil-treated soils on subterranean termite colonies by negating transfer effects. Journal of Economic Entomology 117, 2030–2043. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toae150

Chouvenc, T., Su, N.-Y., 2017. Subterranean termites feeding on CSI baits for a short duration still results in colony elimination. Journal of Economic Entomology 110, 2534–2538. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tox282

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) Bureau of Pesticides, 2023. Termiticides registered in Florida for preventative treatment of new construction. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.fdacs.gov/content/download/91138/file/termiticides-registered-in-florida.xlsx&ved=2ahUKEwiL_bi9o-mKAxUcSzABHQ81DDgQFnoECBkQAw&usg=AOvVaw2wSIATXOEr3njRPdSFqepm

Gordon, J.M., Velenovsky, J.F., IV, Chouvenc, T., 2022. Subterranean termite colony elimination can be achieved even when only a small proportion of foragers feed upon a CSI bait. Journal of Pest Science 95, 1207–1216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-021-01446-4

Hottel, B., 2022. Formosan termites expand northward into Virginia. Pest Management Professional. North Coast Media, LLC, Cleveland, Ohio. https://www.mypmp.net/2022/10/20/formosan-termites-expand-northward-into-virginia/

Hu, X.P., 2005. Evaluation of efficacy and nonrepellency of indoxacarb and fipronil-treated soil at various concentrations and thicknesses against two subterranean termites (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 98, 509–517. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/98.2.509

Hu, X.P., 2011. Liquid termiticides: their role in subterranean termite management. Urban pest management: an environmental perspective. CABI Wallingford UK, pp. 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845938031.0114

Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG), 2011. Global Invasive Species Database. Checklist dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/aaobov accessed via GBIF.org

King, E.G., Jr., Spink, W.T., 1969. Foraging galleries of the Formosan subterranean termite, Coptotermes formosanus, in Louisiana. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 62, 536–542. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/62.3.536

Lee, C.-Y., Neoh, K.-B., 2023. Management of subterranean termites using liquid termiticides. Biology and Management of the Formosan Subterranean Termite and Related Species. CABI GB, pp. 238–272. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781800621596.0012

Lowe, S., Browne, M., Boudjelas, S., De Poorter, M., 2000. 100 of the world's worst invasive alien species: a selection from the global invasive species database. Invasive Species Specialist Group Auckland. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2000-126.pdf

Oi, F., 2022. A review of the evolution of termite control: A continuum of alternatives to termiticides in the United States with emphasis on efficacy testing requirements for product registration. Insects 13, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13010050

Oi, F.M., 2023. Inspection and monitoring. Biology and Management of the Formosan Subterranean Termite and Related Species. CABI GB, pp. 188–216. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781800621596.0010

Potter, M., 2011. Termites. In: Hedges, S., Moreland, D., Eds.), Handbook of Pest Control. Franzak & Foster, pp. 293–441.

Potter, M.F., Hillery, A.E., 2002. Exterior-targeted liquid termiticides: an alternative approach to managing subterranean termites (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) in buildings. Sociobiology 39, 373–405.

Rust, M.K., Su, N.-Y., 2012. Managing social insects of urban importance. Annual Review of Entomology 57, 355–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120710-100634

Scheffrahn, R.H., 2023. Biogeography of Coptotermes formosanus. Biology and Management of the Formosan Subterranean Termite and Related Species. CABI GB, pp. 8–25. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781800621596.0002

Scheffrahn, R.H., Mangold, J.R., Su, N.-Y., 1988. A survey of structure-infesting termites of peninsular Florida. The Florida Entomologist 71, 615–630. https://doi.org/10.2307/3495021

Spink, W.T., 1967. The Formosan subterranean termite in Louisiana. Circular, Louisiana State University 89, 1–12.

Su, N.-Y., 2003. Overview of the global distribution and control of the Fornmosan subterranean termīte. Sociobiology 41.

Su, N.-Y., 2005. Response of the Formosan subterranean termites (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) to baits or nonrepellent termiticides in extended foraging arenas. Journal of Economic Entomology 98, 2143–2152. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/98.6.2143

Su, N.-Y., Lee, C.-Y., 2023. Biology and Management of the Formosan Subterranean Termite and Related Species. CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781800621596.0000

Su, N.-Y., Osbrink, W., Kakkar, G., Mullins, A., Chouvenc, T., 2017. Foraging distance and population size of juvenile colonies of the Formosan subterranean termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) in laboratory extended arenas. Journal of Economic Entomology 110, 1728–1735. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tox153

Su, N.-Y., Scheffrahn, R.H., 1988. Foraging population and territory of the Formosan subterranean termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) in an urban environment. Sociobiology 14, 353–360.

Su, N.-Y., Tamashiro, M., 1987. An overview of the Formosan subterranean termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) in the world. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19891116425

Tseng, S.-P., Taravati, S., Choe, D.-H., Rust, M.K., Lee, C.-Y., 2022. Genetic evidence for multiple invasions of Coptotermes formosanus (Blattodea: Rhinotermitidae) in California. Journal of Economic Entomology 115, 1251–1256. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toac104

Vargo, E.L., Husseneder, C., Woodson, D., Waldvogel, M.G., Grace, J.K., 2006. Genetic analysis of colony and population structure of three introduced populations of the Formosan subterranean termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) in the continental United States. Environmental Entomology 35, 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1603/0046-225X-35.1.151

Yeoh, B.-H., Lee, C.-Y., 2007. Tunneling responses of the Asian subterranean termite Coptotermes gestroi in termiticide-treated sand (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). Sociobiology 50, 457–468.