The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The granulate ambrosia beetle, Xylosandrus crassiusculus (Motschulsky), (once referred to as the 'Asian' ambrosia beetle) is a minute ambrosia beetle of Asian origin that was first detected in the continental United States near Charleston, South Carolina (Anderson 1974). Xylosandrus crassiusculus can become abundant in urban, agricultural, and forested areas. It has been reported as a pest of nursery stock and young trees in the Old World tropics (Browne 1961, Schedl 1962) and of peach trees in South Carolina (Kovach and Gorsuch 1985). It is a potentially serious pest of ornamentals and fruit trees and is reported to be able to infest most trees and some shrubs (azalea), except for conifers (Cole 2008).

Synonyms

- Phloeotrogus crassiusculus Motschulsky

- Xyleborus crassiusculus (Motschulsky)

- Xyleborus semiopacus Eichhoff

- Xyleborus semigranosus Blandford

- Dryocoetes bengalensis Stebbing

- Xyleborus mascarenus Hagedorn

- Xyleborus okoumeensis Schedl

- Xyleborus declivigranulatus Schedl

Distribution

The native range of Xylosandrus crassiusculus is probably tropical and subtropical Asia, and it is widely introduced elsewhere. It is currently found in equatorial Africa, India, Sri Lanka, China, Japan, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, New Guinea, South Pacific, Hawaii, and the United States, where new populations continue to be detected (Wood 1982, Kovach and Gorsuch 1985, Chapin and Oliver 1986, Deyrup and Atkinson 1987, Cole 2008).

In the United States, this species apparently has spread along the lower Piedmont region and coastal plain to North Carolina, Louisiana, Florida (Chapin and Oliver 1986, Deyrup and Atkinson 1987), and East Texas (Atkinson, unpublished). It was collected in western Florida and Alabama in 1983 (Chapin and Oliver 1986), in southern Florida in 1985 (Deyrup and Atkinson 1987), and now is distributed throughout the state. Populations were found in Oregon in and Virginia in 1992, and in Indiana in 2002 (Cole 2008).

Description

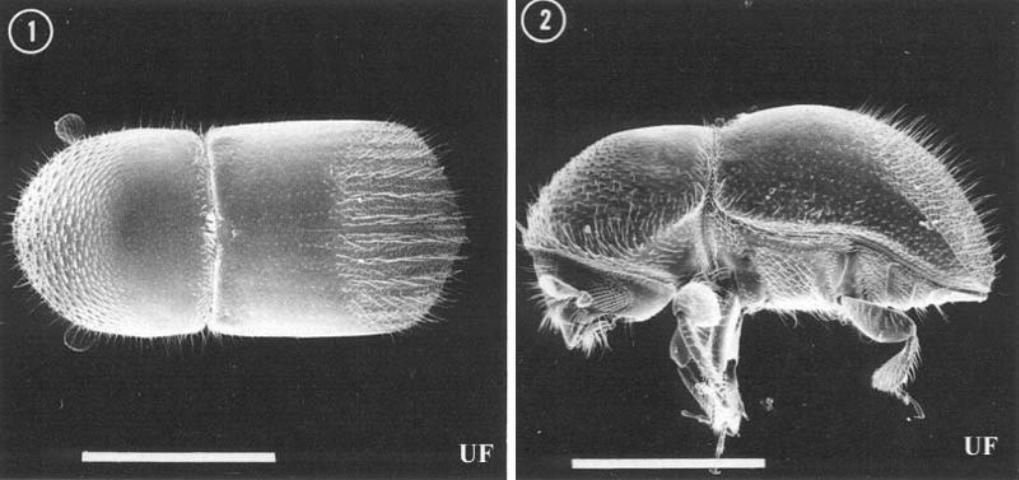

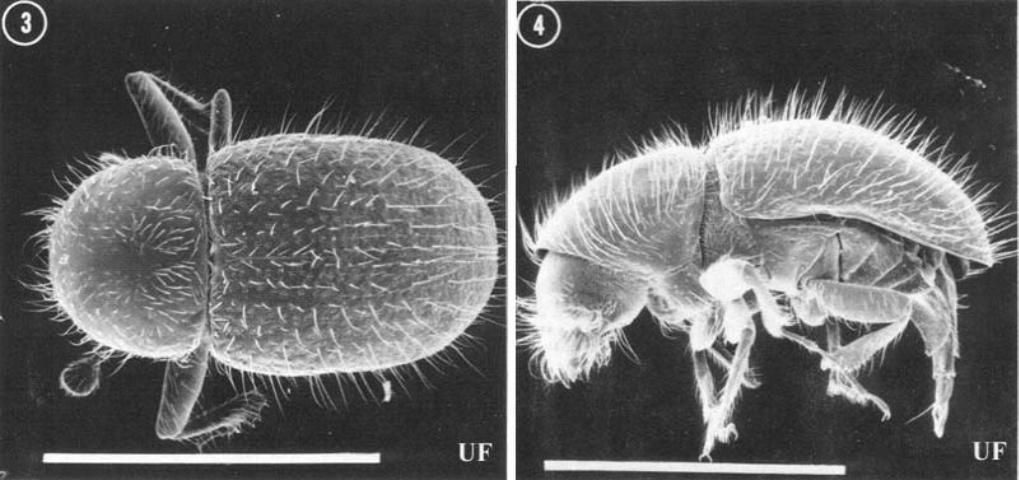

Like other species of the tribe Xyleborini, the head of Xylosandrus crassiusculus is completely hidden by the pronotum in dorsal view, the antennal club appears obliquely cut, and the body is generally smooth and shining. Xylosandrus spp. are distinguished from related genera (Xyleborus, Xyleborinus, Ambrosiodmus) by the stout body, truncate elytral declivity, and non-contiguous procoxae. Female Xylosandrus crassiusculus are 2.1–2.9 mm (~1/16 – 1/8 in) long, stout bodied; the mature color is dark reddish brown, darker on the elytral declivity. Males are much smaller and differently shaped than females, being only 1.5 mm (< 1/16 in) long with a radically reduced thorax and a generally "hunch-backed" appearance. Males are flightless, like those of other xyleborines. Xylosandrus crassiusculus is distinguished from related species in the southeastern United States by its large size (females of other species are 1.3–2.0 mm long (~1/16 in)), and the dull, densely granulate surface of the declivity (smooth and shining in other species). Larvae are white, legless, "C" shaped, and have a well developed head capsule. They are not distinguishable in any simple way from those of other Scolytinae or most Curculionidae.

Credit: Thomas H. Atkimson, University of Florida

Credit: Thomas H. Atkimson, University of Florida

Credit: Paul M. Choate, University of Florida

Biology

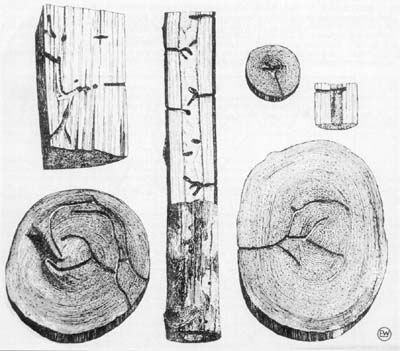

Females bore into twigs, branches, or small trunks of susceptible woody plants, excavate a system of tunnels in the wood or pith, introduce the symbiotic ambrosial fungus, and produce a brood. Like other ambrosia beetles, they feed on ectosymbiotic fungi, which they introduce into their tunnels and cultivate and not the wood and pith of their hosts. Eggs, larvae, and pupae are found together in the tunnel system excavated by the female. There are no individual egg niches, larval tunnels, or pupal chambers. It breeds in host material from 2 to 30 cm (1 – 11 ¾ in) in diameter, although small branches and stems are most commonly attacked. Attacks may occur on apparently healthy, stressed, or freshly cut host material. High humidity is required for successful reproduction. Attacks on living plants usually are near ground level on saplings or at bark wounds on larger trees (Browne 1961, Schedl 1962). Females remain with their brood until maturity. Males are rare, reduced in size, flightless, and presumably haploid. Females mate with their brother(s) before emerging to attack a new host.

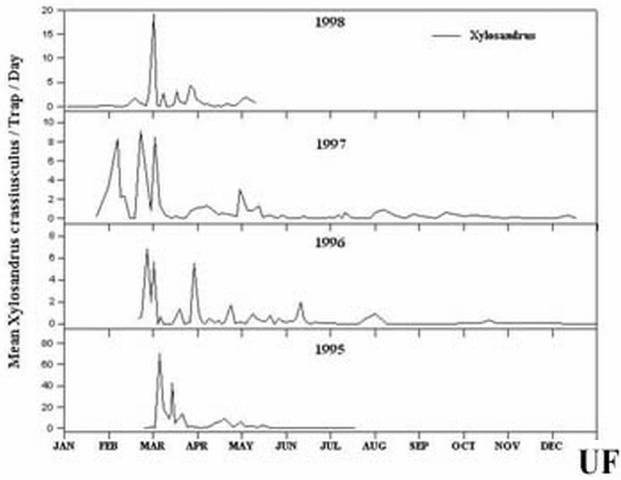

Credit: R.F. Mizell, University of Florida

Hosts

Xylosandrus crassiusculus is capable of breeding in a wide variety of hosts. Schedl (1962) listed 124 hosts, mostly tropical, in 46 families, including Australian pine, cacao, camphor, coffee, mahogany, mango, papaya, rubber, tea, and teak.

Known hosts in the US include aspen, beech, cherry, Chinese elm, crape myrtle, dogwood, golden rain tree, hickory, locust, magnolia, maples, mimosa, oaks, peach, persimmon, plums, Prunus spp., redbud, sweet gum, tulip poplar, and walnut (Cole 2008). Bradford pear and pecan as hosts are commonly attacked in Florida and in the southeast US.

Damage

Large numbers of attacks were found in Shumard oaks along the lower 1 m (3.3 ft) of stem in 3 m (9.8 ft) saplings with no other symptoms of disease, attack by other insects, or visible stress. Female beetles were boring into green, fresh, unstained portions of the stems. Visible symptoms included wilted foliage and strings of boring dust from numerous small holes. The large numbers of attacks apparently resulted in the death of the trees. Large Drake elm saplings showed isolated attacks on the lower stems, which did not directly kill plants. Subsequently, large cankers formed at the site of attacks, in some instances resulting in the death of trees by girdling. This type of damage is similar to that reported by Browne (1961) and Schedl (1962). Kovach and Gorsuch (1985) reported attacks on branches of apparently healthy young peach trees in coastal South Carolina.

Xylosandrus crassiusculus was a major component of an ambrosia beetle infestation in the sapwood of sweetgum logs in a Chiefland, Florida, millyard during September 1999. Clearly, infestations are not limited to small living trees, nor does flight occur only in the Spring. The millyard problem was basically due to storing too many logs too long before processing. Logs were cheap at the time, and the mill had a six-month rather than a one-month inventory. The mill ended up losing more than it had saved by purchasing an excess inventory at low prices.

Credit: R.F. Mizell, University of Florida

Credit: Schedl (1962)

Management

Pyrethroids have been found to provide control of attacking adults if applied prior to the closing of the galleries with frass. Once the beetles are in the tree and have frass packed in the entry holes they are isolated from the outside. If infestations occur, affected plants should be removed and burned, and trunks of remaining plants should be treated with an insecticide labeled for this pest or site and kept under observation. Any obvious conditions causing stress to trees should be corrected.

Credit: R.F. Mizell, University of Florida

Florida Insect Management Guide for insect borers of trees and shrubs

Selected References

Anderson DM. 1974. First record of Xyleborus semiopacus in the continental United States (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). U.S. Department of Agriculture Cooperative Economic Insect Report 24: 863–864.

Bambara S, Sorensen K, Baker JR, Casey C. (March 2003). The Asian ambrosia beetle. Ornamentals and Turf Insect Notes. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/granulate-asian-ambrosia-beetle (12 May 2020).

Browne FG. 1961. The biology of Malayan Scolytidae and Platypodidae. Malayan Forest Records 22: 1–255.

Chapin JB, Oliver AD. 1986 New records for Xylosandrus and Xyleborus species (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 88: 680–683.

Cole, KW. (January 2008). Granulate Ambrosia Beetle. Indiana Department of Natural Resources. https://www.in.gov/dnr/entomology/files/ep-GranulateAmbrosiaBeetleFactsheet.pdf (2 February 2022).

Deyrup MA, Atkinson TH. 1987. New distribution records of Scolytidae from Indiana and Florida. Great Lakes Entomologist 20: 67–68.

Hudson W, Mizell RF. 1999. Management of Asian ambrosia beetle, Xylosandrus crassiusculus, in nurseries. Proceedings of the Southern Nursery Growers Association 44:198–201.

Kovach J, Gorsuch CS. 1985. Survey of ambrosia beetle species infesting South Carolina peach orchards and a taxonomic key for the most common species. Journal of Agricultural Entomology 2: 238–247.

Mangold JR, Wilkinson RC, Short DE. 1977. Chlorpyrifos sprays for control of Xylosandrus compactus in flowering dogwood. Journal of Economic Entomology 70: 789–790.

Mizell RF, Bolques A, Crampton P. 1998. Evaluation of insecticides to control the Asian ambrosia beetle, Xylosandrus crassiusculus. Proceedings of the Southern Nursery Growers Association 43: 162–165

Schedl KE. 1962. Scolytidae und Platypodidae Afrikas. II. Rev. Ent. Mozambique 5: 1–594.

Solomon JD. 1995. Guide to Insect Borers of North American Broadleaf Trees and Shrubs. Agricultural Handbook 706. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service 735 pp.

Wood SL. 1982. The bark and ambrosia beetles of North and Central America (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), a taxonomic monograph. Great Basin Naturalist Memorandum 6: 1–1359.