- Scientific Name: Punica granatum L.

- Family: Punicaceae

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Orgin and History

Pomegranates are native to central Asia and were grown in ancient Persia, Babylon, Egypt, and India. It was reported that common pomegranates were first cultivated in Persia (today Iran) during 3,000 BC. Cultured extensively in Spain, pomegranates moved with missionaries into Mexico and California in the 16th century. For commercial production, the economic potential for growing pomegranates in Florida is currently unknown at this time. Research continues on the possibility of finding pomegranates cultivars that can grow in Florida. Florida's wet season, accompanied by hot weather, are factors that reduce the fruit quality due to disease pressure, especially for late-season varieties such as 'Wonderful'. It is worth noting that the major commercial cultivar 'Wonderful' originated in Florida. To reduce disease pressures and avoid marketing competition with California pomegranates, research for Florida production needs to focus on finding earlier varieties that can be harvested in July and August.

Climate

Pomegranates can be grown in mild-temperate to tropical climates. However, the best quality pomegranate fruit are produced in regions with cool winters and hot, dry summers (Mediterranean climate). Pomegranate is more cold hardy than citrus. However, pomegranate cultivars vary in frost tolerance. In some cases temperatures down to 12°F (-11°C) may severely injure dormant trees (Figure 2); non-dormant trees can be damaged by higher temperatures (Figure 3). Several thousand acres are cultivated in California and a few growers are conducting regional trials with different varieties in Florida, Georgia, Arizona, Texas, and other states in the US.

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Description

Normally a dense, bushy, deciduous shrub, 6‒12 ft (2‒4 m) tall, the plant has slender, somewhat thorny branches. It may be trained as a small tree reaching 12–20 ft (4‒7 m) in height.

Pomegranate is an attractive ornamental plant and there are some varieties available for ornamental purposes, which do not produce fruit (Figure 4).

Credit: A. Yavari

Pomegranate leaves are glossy, dark green, oblong to oval, and 1‒1.25 in. (2.5‒3 cm) long. Leaves are arranged opposed and pairs alternately crossing at right angles and clustered on short branchlets (Figure 5).

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Blooms are a flaming orange-red, 1.5‒2.5 in (4‒6 cm) in diameter with crinkled petals and numerous stamens. Flowers are borne solitary or in small clusters angled towards the end of branchlets. Flowers are 'perfect', containing both male and female parts; however, pomegranate trees generally carry two types of flowers; namely female (productive, Figure 6) or male (non-productive, Figure 7). In male flowers, the pistils are not developed as in female flowers and they do not produce fruit. Flowers are generally self-pollinated.

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Pomegranates are brownish-yellow to purplish-red berries 2‒5 in (5‒12 cm) in diameter with a smooth, leathery skin. Fruits are spherical, somewhat flattened, with a persistent calyx (Figure 8). The calyx may be 1.5‒2.5 in (1‒6 cm) long. Numerous seeds are each surrounded by a pink to purplish-red, juicy, sub-acid pulp (aril), which is the edible portion. The pulp is somewhat astringent. Pomegranates grown in North Florida mature from July to November, but may produce year-round in South Florida.

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Cultivars

'Wonderful' cultivar (Figure 9) is grown commercially in California from cuttings from Florida. Florida's wet season, accompanied by hot weather, are factors that reduce the fruit quality of late-season fruiting of pomegranate varieties such as 'Wonderful'. Therefore, the late-ripening 'Wonderful' variety might not be the suitable cultivar for Florida. Also, earlier-ripening cultivars that mature in July and August will avoid marketing competition with California pomegranates. However, the economic potential for growing pomegranate trees commercially in Florida is currently unknown at this time.

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

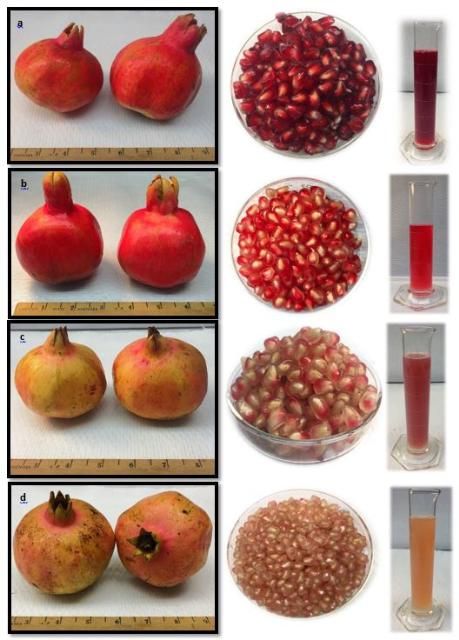

There are many pomegranate cultivars with different fruit characteristics that are grown in Florida. Research continues on the possibility of finding pomegranate cultivars that can grow in Florida (Figure 10). Today, pomegranate can be purchased at a few supermarkets not only as whole fruit and juice but also as packed arils. An automated aril extraction machine with the capability of extracting arils of 100 ton pomegranate fruit per day has been developed. There is a possibility that different pomegranate varieties with different aril colors can be marketed in the future. However, more studies and sensory tests are needed on the fruit characteristics of varieties grown in Florida. Intial evaluations of some pomegrante varieties indicate that those varieties that do not produce fruit with good shape, size, and appearance in Florida might be suitable for either packed arils or juice (Figure 10). Diseases that develop during Florida's hot/wet growing season reduce the quality of the fruit and remain a major limitation to production.

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Propagation

Trees are easily propagated during winter from hardwood cuttings 6‒8 in (15‒20 cm) in length and pencil size or larger in diameter (Figure 11). In Florida, hardwood cuttings should be taken in January or February and placed vertically in soil with the 2‒4 top nodes exposed. Cuttings may be left in nursery rows for 1 to 2 years. Seed-propagated plants do not come true-to-type, but seeds will germinate in 45‒60 days. Layering is also successful but more labor-intensive.

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Soils

Pomegranates produce best on deep, loams, but are adapted to many soil types from pure sand to heavy clay. Yields are usually low on sands, while fruit color is poor on clays. Growth on alkaline soils is poor. Optimum growth is associated with well-drained, not heavy or moist soils in the pH range of 5.5‒7.0.

Irrigation

Water requirements for pomegranate are about the same as for citrus, 50‒60 in (125‒150 cm) per year. Trees should be irrigated every 7‒10 days in the absence of significant rainfall. During maturation, it is usually recommended to reduce the irrigation gradually in order to reduce splits but also to enhance flavor and color development. Summer rains might be an issue in some parts of Florida. Sudden changes in irrigation amounts and timing often lead to fruit splitting, especially a few weeks before harvesting. Maintain adequate soil moisture in late summer and early fall to reduce potential fruit splitting. Pomegranates are tolerant of some flooding.

Planting and Spacing

Plant trees in early spring (February‒March), avoiding late frost. Soil should be loosely worked and not wet. When used as a hedge, plants are spaced 6-9 ft (2-3 m) apart. Suckers will fill spaces and produce a compact hedge. The spacing of 10-16 ft (3-5 m) between plants and 13-20 ft (4‒6 m) between rows are used for orchards, and similar spacing should be maintained for dooryard trees (Figure 12).

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Training and Pruning

Trees tend toward a bushy habit with many suckers arising from the root and crown area. For commercial production, trees need to be trained by allowing only a few or one trunk to develop (Figure 13). Additional suckers should be removed frequently around the main trunk(s). Prune to produce stocky, compact framework in the first 2 years of growth. Cut trees back to 2‒2.5 ft (60‒75 cm) at planting and develop three to five symmetrically spaced scaffold limbs by pinching back new shoots, the lowest at least 8‒10 in (20‒25 cm ) from the ground. Shorten branches to 3/5 of their length during the winter following planting. Remove interfering branches and sprouts leaving two or three shoots per scaffold branch.

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Light, annual pruning of established trees encourages production of good quality fruit. Remove dead or damaged wood during late winter. Remove sprouts and suckers as they appear.

Fruit bearing branches will bend or break unless fruit thinning is practiced or pruning is done in a way to reduce crop load. Fruit that touches the ground will rot or be damaged by pests (Figure 14).

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Special Considerations

Pomegranate trees are self-pollinating. Severe fruit drop during the plant's juvenile period (3‒5 years) is not uncommon. Fruit drop is aggravated by practices favoring vegetative growth, such as over-fertilization and excess irrigation. Avoid putting young trees under stressful conditions. Fruit drop is less severe on mature trees than on younger trees.

Diseases

The most destructive disease observed in Florida is anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum sp. (Figure 15). It can affect leaves, stems, flowers, and fruit. Leaf symptoms include small, circular to angular, dark, reddish-brown to black areas, 0.25 in (4‒5 mm) in diameter. Infected leaves are pale green and fall prematurely. Fruit symptoms are small, conspicuous, dark brown spots, initially circular, becoming irregular. At least three sprays per year of neutral copper fungicide can reduce the disease impact.

Credit: G. Vallad, UF/IFAS

Insects

Scale and mites occasionally attack the plant, but these do little damage. Sulfur dust applied in early June offers good mite control. Scale insects can be controlled by an application of 3% oil spray during the winter when the leaves are not present. Tree borers can also infest and kill trees (Figure 16).

Credit: Ali Sarkhosh, UF/IFAS

Dr. Bill Castle (professor emeritus, Horticultural Sciences Department, UF/IFAS) has developed a pomegranate website for Florida, http://www.crec.ifas.ufl.edu/extension/pomegranates, that contains more detailed information on pomegranate botany, culture, cultivars, nurseries, grower associations, and other information. Those interested in learning more about pomegranates in Florida are encouraged to view this website.

References

Holland. D., K. Hatib, and I. Bar-Ya'akov. 2009. "Pomegranate: botany, horticulture, breeding." Horticultural Review. 35: 127–191

Sarkhosh, A., Z. Zamani, R. Fatahi, and M. Sayyari. 2009. "Antioxidant activity, total phenols, anthocyanin, ascorbic acid content and woody portion index (wpi) in Iranian Soft-Seed pomegranate Fruits." Global Science Books. Food. 1: 68‒72.

Sarkhosh, A., Z. Zamani, R. Fatahi, H. Ranjbar, and M. R. Vazifeshenas. 2008. "Evaluation of Iranian soft-seed pomegranate accessions by using simple and multivariate analysis methods." Tree and Forestry Science and Biotechnology. 2: 18‒25.

Zamani, Z., A. Sarkhosh, R. Fatahi, and A. Ebadi. 2007. "Genetic relationships among pomegranate genotypes studied by fruit characteristics and RAPD markers." The Journal of Horticulture Science & Biotechnology. 82: 11‒18.