Summary

- Lethal bronzing disease (LB) used to be called Texas Phoenix Palm Decline (TPPD).

- Lethal bronzing (LB) disease was discovered in Florida in 2006 and is caused by a phytoplasma—a type of bacteria that lacks a cell wall and cannot be cultured with artificial media.

- The LB phytoplasma is similar to but genetically distinct from the phytoplasma that causes lethal yellowing (LY) disease of palms.

- The LB phytoplasma is limited to the phloem (sap) of the palm and cannot survive outside a plant or insect; therefore, it cannot be mechanically transmitted (e.g., by pruning tools or infected roots touching new roots).

- Once a palm shows symptoms and tests positive for the LBD phytoplasma, it should be removed immediately.

- Healthy palms near infected palms should be tested to verify they are free of infection and injected with oxytetracycline HCl (OTC) every three to four months as a preventative for at least two years.

Introduction

In late 2006, a novel phytoplasma disease was identified in Hillsborough County, Florida, in the Tampa area. The phytoplasma was isolated from edible date palm (Phoenix dactylifera), wild date palm (Phoenix sylvestris), Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis), and Queen palm (Syagrus romanzoffiana). In 2008, the phytoplasma was subsequently isolated from the Cabbage palm (Sabal palmetto). The disease was first called Texas Phoenix Palm Decline (TPPD) because it was found to be the same pathogen isolated from P. canariensis in Texas in the early 2000s. Due to the expansion of the disease into Florida and Louisiana as well as its discovery in Mexico and the fact that it infected palms outside the genus Phoenix, the name was changed to lethal bronzing (LB) disease in order to reflect the symptoms seen in various hosts.

Pathogen

Lethal bronzing disease is caused by a phytoplasma, an unculturable bacterium that has no cell wall. Among phytoplasmas, the LB agent has been classified as ’Candidatus Phytoplasma aculeata’. The signature DNA sequence obtained from LB phytoplasma in Florida is a perfect match to the signature barcode of the phytoplasma known to cause LB on P. canariensis (Canary Island date palm) in the Corpus Christi area of Texas. Analysis of DNA has determined the LB phytoplasma is related to but genetically distinct from the phytoplasma that causes LY.

Phytoplasmas live in the part of the plant where sap is transported (phloem tissue). Phytoplasmas are transmitted to plants by piercing-sucking insects that feed on the sap. The insects spread the phytoplasma from plant to plant as they visit different hosts during their feeding activities. Phytoplasmas are not known to survive outside their host, whether the host is plant or insect. Planthoppers and leafhoppers are the main groups of insects that transmit phytoplasmas.

Symptoms

The first symptoms of LB are variable. However, if fruit is present, the first symptom is generally premature fruit drop (Figure 1). If fruit has not set but inflorescences are present, they will become necrotic (Figure 2). Note that if the palm is not old enough to produce fruit, if it is not putting out an inflorescence at the time of infection, or if the inflorescences are trimmed, then these will not be reliable indicators for infection status. Inflorescence necrosis/fruit drop progresses to discoloration of the oldest leaves (closest to the ground) that gradually advances to younger leaves (Figure 3). The final stage of the disease is the collapse of the spear leaf, indicating that the heart or bud of the palm (apical meristem) has died and the palm has completely declined with no chance of saving it. The length of time between infection and symptom development (latent period) appears to be about four to five months. From symptom development to collapse of spear leaf is about two to three months, but this is highly variable. In some cases, no leaf discoloration is observed, but the spear leaf will collapse and the palm will test positive. Symptom progression occurs at different rates in different palm species.

Credit: Brian Bahder, UF/IFAS

Credit: Brian Bahder, UF/IFAS

Host Range and Distribution

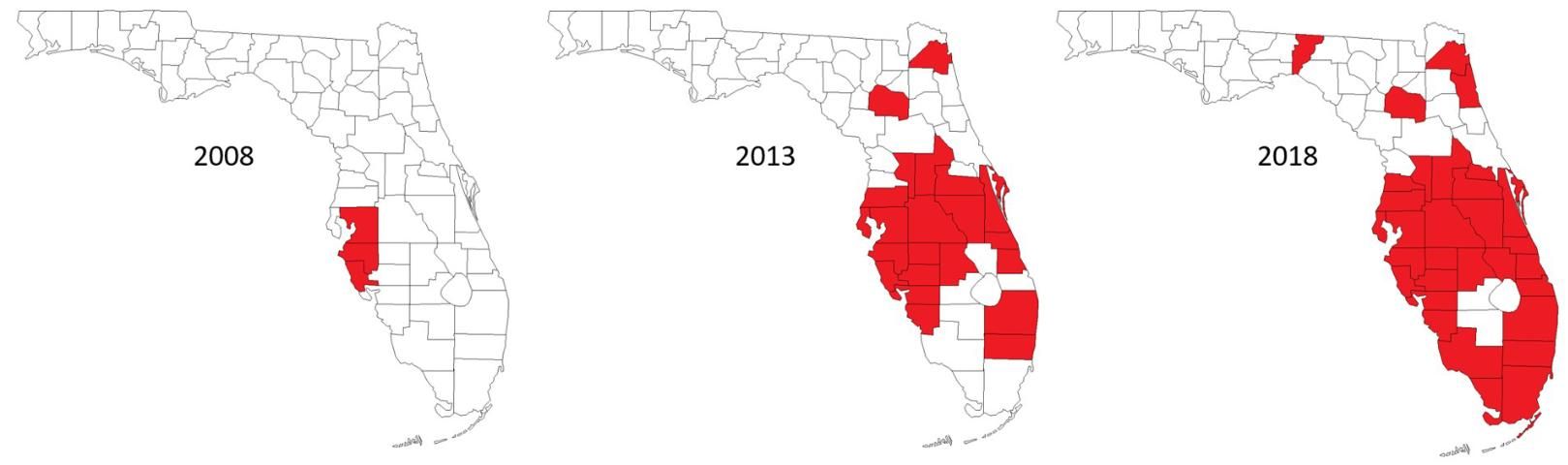

Currently, the LB phytoplasma has been found in 21 different species of palm (Figure 4, Table 1). As the disease becomes more established in Florida and spreads further south into areas with higher palm diversity, the host range could expand. Also, since the introduction of LB to the state of Florida, it has been isolated from palms in 36 different counties (Figure 5, Table 2). To date, the disease is most prevalent in the central part of Florida, but is spreading farther north and south, with Jacksonville being the northernmost limit and the Florida Keys being the southernmost record. The disease has also been reported in Louisiana.

Credit: Brian Bahder, UF/IFAS

Credit: Brian Bahder, UF/IFAS

Management

Management of LB involves removal of infected palms and preventative injection of antibiotics. Current data suggests that once palms start showing symptoms, the label rate for the antibiotic oxytetracycline-hydrochloride is not sufficient for symptom reversal. Because of this, upon symptom development and/or a positive test result, a palm is considered lost and should be removed immediately to reduce the amount of time this source of phytoplasma exists in the environment. The longer it is left, the higher probability that further spread will occur. Sampling healthy-looking palms around symptomatic palms can help get ahead of the disease because healthy-looking palms can also test positive. Even though no symptoms are present, those palms still need to be removed because there will not be sufficient time for the antibiotic to take effect before symptoms develop. Also, by testing healthy-looking palms, you can identify which palms are not infected and start preventative injections with the antibiotic.