Of the more than 4,000 known plant species growing in Florida, approximately 30% are not native to Florida or the Southeast. Organisms are considered non-native when they occur artificially in locations beyond their known historical native ranges. The term non-native can refer to species brought in from other continents, regions, ecosystems, and habitats. The most important aspect of a non-native (exotic) plant is how it responds to a new environment. An invasive species is one that displays rapid growth and spread, allowing it to establish over large areas. Invasive species are free from the complex array of natural controls, including herbivores, parasites, and diseases, that are present on their native lands. The term noxious is a legal designation used specifically for plant species that have been determined to be major pests of agricultural ecosystems and are subject by law to certain restrictions.

Known ecological impacts of invasive plants include reduction of biodiversity; loss of and encroachment upon endangered and threatened species; loss of habitat for native insects, birds, and other wildlife; alterations to the frequency and intensity of fires; and disruption of native plant-animal associations such as pollination, seed dispersal, and host-plant relationships. In addition, invasive plants can hybridize with native plants and alter their genetics; they grow rapidly, sometimes girdling native shrubs and trees; they increase the incidence of plant stress in forested areas; and they reduce the amount of space, water, sunlight and nutrients that would otherwise be available for native species. All invasive species (including plants, arthropods, and vertebrates) have an estimated annual cost to the United States of $120 billion annually (USFWS, 2012). The cost to the US economy of invasive plants alone is estimated at $21 billion (WUSF, 2022).

In all forest operations it is important to consider that any mechanical disturbance of the soil with heavy equipment could potentially promote the establishment and spread of invasive exotic plants. It is important to monitor all mechanically managed sites for subsequent invasive plant establishment. Early detection and removal of invasive plants is the key to successful management. This publication describes many of the current methods used to manage some of the more common and troublesome invasive exotic plants in north Florida forests. These pest species may occur in established forest stands or when establishing new plantations. Consult the sources referenced in this paper for additional details about these and other methods. Control methods usually involve some combination of fire and mechanical and chemical treatments. Biological control agents for some of these plants are currently under investigation. Pictures of these species can be found at: https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AG108, or in Langeland and Burks's book, Identification and Biology of Non-Native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas: http://ifasbooks.ifas.ufl.edu/p-197-identification-and-biology-of-non-native-plants-in-floridas-natural-areas.aspx.

Alternative Ways to Control Woody Plants

Prescribed fire is an important and natural means to manage forest vegetation. Sometimes fire is used in combination with hand weeding, mechanical removal, or herbicide treatment to manage invasive vegetation and also to restore native vegetation. Unfortunately, most invasive plants in forests, including cogongrass, Chinese tallowtree, Chinese privet, and Japanese climbing fern, cannot be controlled by fire alone.

Hand-weeding can be effective when removing new or small infestations and when plants are small, but often this labor-intensive approach is impractical. The use of machinery in invasive weed management may include mowing, disking, plowing, grinding (masticating), root-raking/wrenching, and other approaches. However, many invasive species re-sprout to reoccupy the site unless all plant parts are removed, particularly the roots. In some cases (e.g., cogon-grass), disking or breaking up the roots may in fact increase the population of the invasive species. When using heavy equipment to remove invasive plants, ensure that all equipment is cleaned off before it leaves the treatment site to prevent further spread of the problem species.

Chemical treatment recommendations described in this publication have provided acceptable levels of control in experimental trials and operational experience, and are consistent with product labeling. Always follow current herbicide label instructions for determining approved application use sites (i.e., "forests"), herbicide application rates, mixing instructions, personal protective equipment, and use precautions. Additional information about various herbicides used in forestry applications may be found in:

Osiecka, A., and P. J. Minogue. 2020. Forest Herbicide Characteristics. FOR283. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FR345

Osiecka, A., and P. J. Minogue. 2021. Considerations for Developing Effective Herbicide Prescriptions for Forest Vegetation Management. FOR273. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FR335

Ferrell, J., K. Langeland, and B. Sellers. 2019. Herbicide Application Techniques for Woody Plant Control. SS-AGR-260. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AG245

Trees/Shrubs

Heavy machinery, such as bulldozers, may be used to physically remove large trees or shrubs. This is a common approach to prepare land for tree plantation establishment, but using large equipment in established stands to remove invasive trees and shrubs may cause excessive soil and root disturbance and damage to desired vegetation. Hand tools, such as shovels or root-wrenches, may be used to remove small trees and shrubs (Miller et al. 2010), but this is labor intensive and may not be effective in removing all of the roots.

Periodic prescribed fire is an important tool to manage invasive trees and shrubs, and is most effective on thin-barked species, smaller stems and when burns are conducted during the growing season.

Backpack or hand-held sprayers, ground machinery, and helicopters are used to apply herbicides to control invasive trees, shrubs, and other plants in forests. Herbicide treatments may be broadcast for large infestations, but applications to individual plants provide better selectivity, minimizing adverse effects to desired vegetation. Individual stem approaches also use the least amount of herbicide. Several approaches employed for individual plant control are described below. The choice of application method depends on the size of the plants, the density of the infestation, and the extent of the area to be treated.

- Broadcast herbicide applications may be made with ground-based sprayers or aircraft where large continuous infestations are present.

- Cut stem treatment involves cutting through the bark of trees or large shrubs at a downward angle using a hatchet or machete, and then applying a small amount of herbicide solution into the cut using a common garden squirt bottle or similar straight-stream sprayer such as the Spraying Systems Gun-Jet® applicator (Glendale Heights, IL).

- Cut stump treatment is used for recently felled trees, saplings, and large shrubs. A small amount of diluted herbicide solution is applied to the cambium layer. The cambium is an actively growing, light green or brown ring just inside the bark.

- Basal bark treatment involves applying diluted herbicide solution or oil emulsion to the lower 12 to 16 inches of the stem or stems of undesirable saplings or shrubs. This approach is most effective when stem diameters are less than 3 inches and is often chosen when stem density is high (many small stems). Larger trees (4–6 inches in diameter) that have very thin bark may also be controlled with this method. However, this is often highly species specific.

- Backpack foliar sprays are used to control individual invasive trees and shrubs where their crowns may be reached with backpack or handheld sprayers. This approach is chosen when stems are scattered and the tallest crowns are less than 8 feet tall. It is difficult to get adequate coverage on taller trees and spray contact to desired vegetation is more likely as spray height increases. To control taller invasive trees or shrubs, cut stem or cut stump treatments (after tree felling) are more effective to selectively remove invasive trees.

Application Timing: For deciduous trees and shrubs, foliar broadcast or backpack foliar individual stem applications are effective from full leaf-out in spring until just prior to the onset of fall colors. Some evergreen species such as coral Ardisia may be treated with foliar sprays during the dormant season, which may lessen negative effects to desired vegetation nearby. Cut stem, cut stump, and basal bark treatments can be performed at any time of the year. However, early spring treatments may not be effective when strong upward sap flow may force herbicide from the cuts or treated surface.

When deciding on the best treatment approach for the invasive tree or shrub species listed below, consider the plant size and infestation density to select the appropriate application method (broadcast foliar, backpack foliar, cut stem, cut stump, or basal bark) and refer to Tables 1–9 for application rates and special concerns. Often a combination of approaches for different species or stem sizes is most efficient. Always read and follow all label directions.

Chinese Tallow (Triadica or Sapium sebifera)

Credit: Nancy Loewenstein, Auburn University

Chinese tallow, a.k.a. popcorn tree or tallowtree, was introduced by Benjamin Franklin from France as a source of candle wax and widely introduced from China in the early 1900s as an ornamental. It has since invaded most southeastern states. It is a small tree whose large, fleshy seeds are widely dispersed by birds and water runoff. The tree's attractive, light green, broadly ovate leaves that yield bright yellow and orange fall colors have made it a popular ornamental. It is also used by beekeepers for honey production in spring. However, this tree is threatening to become the prominent component of marshes, river margins, and dry uplands within its expanding range. Further planting of this tree is prohibited by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS), and it is listed as a noxious weed by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and as a Category 1 invasive weed by the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council (FLEPPC).

Credit: Nancy Loewenstein, Auburn University

Control

For control of Chinese tallow in pine plantations, Arsenal® AC or Chopper® (both contain the active ingredient imazapyr) are commonly used. Southern pines are tolerant to these persistent soil-active herbicides but can still sustain some injury if the trees are stressed or if high concentrations of herbicide are applied. Hardwood trees and shrubs are susceptible to damage from these herbicides and will likely be injured or killed if their roots extend into the treated area. When managing Chinese tallow in hardwood forests, or close to desired vegetation, apply Garlon® (triclopyr) or Accord® XRT II (glyphosate) to provide better selectivity. Please see Table 1 for methods of application and herbicide rates.

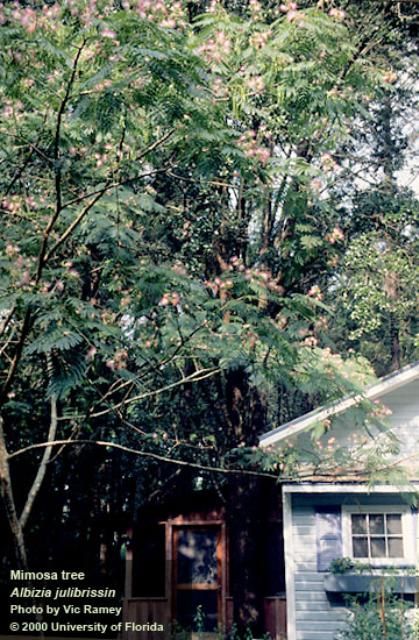

Mimosa or Silk Tree (Albizia julibrissin)

Credit: Ann Murray, UF/IFAS

Mimosa is a small to medium-sized tree with attractive, fern-like leaves and showy pink flowers. It establishes vigorously on disturbed areas, often spreading by seed from nearby ornamentals. It was introduced to the United States as an ornamental in 1745 and continues to be used as such because of its attractive form, foliage, and flowers. It reproduces both vegetatively and by seed. If cut or top-killed, it will re-sprout quickly, growing in height to three feet or more in a single season. Due to its ability to grow and reproduce along roadways and disturbed areas, and its tendency to readily establish after escaping from cultivation, mimosa is considered a Category II invasive by Florida's Exotic Pest Plant Council.

Credit: Vic Ramey, UF/IFAS

Control

Mimosa can be controlled with the use of mechanical (repeated cutting, chopping, mowing) and chemical treatments. Because this tree is prone to re-sprout following cutting, chemical treatments are most effective for complete control. Mimosa is a legume and these plants are particularly susceptible to Milestone® (aminopyralid), Escort® (metsulfuron methyl), and Transline® (clopyralid) herbicides. Most native perennial grasses show tolerance to these herbicides, so damage to desired species should be minimal during restoration efforts. Arsenal and Chopper are not effective for control of legumes and are not recommended for mimosa control. See Table 2.

Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense), Japanese Privet (Ligustrum japonicum), and Glossy Privet (Ligustrum lucidum)

These members of the olive family are shade-tolerant, tall, evergreen-leaved shrubs that can grow to about 30 feet in height. They spread by bird-dispersed seeds or underground runners and form dense stands that prevent pine and hardwood regeneration and/or land access. These plants were introduced from Asia.

Credit: Ann Murray, UF/IFAS

Control

Adequate control of these shrubs can be achieved through a variety of herbicide application methods and several herbicide products are effective. The addition of 1% methylated seed oil (MSO) additive to foliar sprays improves herbicide uptake through the waxy cuticle of invasive privets. Often dense thickets of privet need to be cut down or mowed to gain access and the new sprouts treated with herbicides. See Table 3.

Coral Ardisia (Ardisia crenata)

Credit: Ann Murray, UF/IFAS

Coral ardisia, or spice ardisia, is an evergreen shrub, 2–6 ft tall, with dark green, scallop-margined leaves. Flowers and fruit are produced in axillary, not terminal, clusters, usually drooping below the foliage. Fruits are small, bright red, one-seeded drupes. It was introduced into Florida for ornamental purposes in the early 1900s and has spread and become naturalized in hardwood hammocks across the north and central parts of the state. It does not grow well in full sunlight. Seedlings of native plant species are shaded out where it forms dense stands.

Credit: Ann Murray, UF/IFAS

Control

Seedlings can be hand-pulled. Mowing can keep the plants at ground level and inhibit seed production, but most effective control of this plant can be achieved through herbicide application. The recommended herbicide treatments application timing in mid- to late-fall, when many native desirable plants are dormant, improves selectivity in control. This species has waxy leaves so an oil-based herbicide or surfactant additive will increase effectiveness of the treatment. See Table 4.

Vines

Kudzu (Pueraria montana)

Credit: Jeff Schardt, FDEP

Kudzu was introduced into the United States at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. By 1900 kudzu was available through mail order as an inexpensive livestock forage, and was later promoted by the USDA for erosion control along rights-of-way and gullies. It now persists in impenetrable patches as large as 100 acres and will overtop and kill trees, even after they are mature. Kudzu is an aggressive leguminous vine capable of growing 1 foot per day. It can easily grow 60 feet in a single growing season. It also roots at the nodes, establishing new root crowns on vines growing on the ground. Kudzu patches may become difficult to traverse as vines layer on top of each other and often conceal stumps or old gullies.

Credit: Ann Murray, UF/IFAS

Control

Special effort is required to control kudzu. The older the patch, the harder it will be to control and the longer it will take for complete eradication. In severe cases, follow-up spot treatments may be required for several years.

It is best to first evaluate the kudzu problem by determining the age of the patch. Do this by looking at the root crowns (the top of the primary root). If the root crowns are 2 inches or larger in diameter, the patch is about 10 years of age or older. For older kudzu stands, the higher end of labeled rates are recommended. For easiest access, it is best to evaluate kudzu problems in winter, when vines and foliage are withered.

The most effective treatment for kudzu control is a combined application of Escort and Accord XRT herbicides in high application volume (Table 5). However, even this treatment will require annual spot treatment of emerging crowns to eradicate the infestation. The Escort in the mix has soil residual and will injure nearby trees or shrubs by root uptake.

Where kudzu is draping trees, a foliar application of Transline (Table 5) provides effective control. Transline treatments require many sequential annual applications to gain control. Please see Table 5 for a list of the 25 Florida counties where it is permissible to use Transline.

Air Potato (Dioscorea bulbifera)

This invasive vine from Asia (Croxton et. al. 2011) was introduced into Florida in 1905. It quickly grows to 60–70 feet in length, high enough to overtop and shade out native trees. The air potato is a member of the yam family and produces many aerial tubers (potato-like growths) called bulbils that are attached to the vines. Bulbils eventually establish and grow into new plants. It is listed as a Category I invasive by FLEPPC.

Credit: Ann Murray, UF/IFAS

Control

Begin by collecting all bulbils, if any, from the ground and removing them from the site. Dispose of the bulbils by putting them in a garbage bag and placing it with yard debris for pick-up or by burning. Composting is not effective. Municipalities dispose of them by incinerating them or incorporating them into hard turf. Bear in mind that many tubers will be underground: either dig them up or apply herbicide to their emergent vines before they can produce more bulbils.

Once this is done, adequate control can be achieved with the use of herbicides. Guidelines for herbicide control are listed below. Follow-up treatments may be necessary in all cases. See Table 6.

Biological Control

The air potato leaf beetle (Lilioceris cheni) is a rather large (approximately 9 mm or about 3/8 inch long) orange-red Asian leaf beetle in the subfamily Criocerinae (see image). It was first collected in Nepal in 2002, and later in China in 2010 and 2011. The beetle is a host-specific specialist that feeds and develops only on the air potato vine. This insect has been effective at controlling the plant since its first release in 2012. By the end of 2015, approximately 450,000 beetles have been released at more than 2,000 locations in Florida (Center 2015).

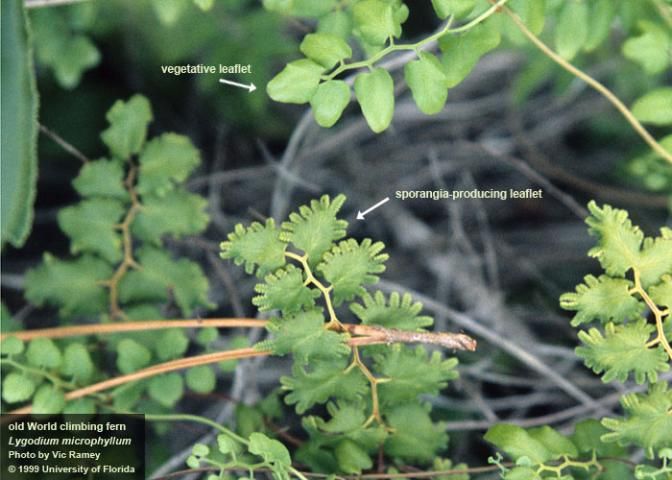

Japanese Climbing Fern (Lygodium japonicum) and Old World Climbing Fern (Lygodium microphyllum)

Japanese climbing fern is native to Asia. It is a perennial, delicate looking, climbing vine that forms dense stands that can cover trees and shrubs. Introduced from Japan as an ornamental, it is naturalized throughout the lower portions of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina, North Carolina, and south into central Florida. Further planting of this vine is prohibited by FDACS.

Credit: Ann Murray, UF/IFAS

Old World climbing fern is native to Asia and Australia. It also climbs rapidly into trees and shades out native vegetation. It now covers hundreds of acres in south and central Florida. Old World climbing fern has the ability to "re-sprout" from almost anywhere along each climbing leaf. Dense growth of the plant can also be a fire hazard, frequently enabling small ground fires to reach into tree canopies and kill the growing branches.

Japanese and Old World climbing ferns are presently the only non-native invasive ferns in the South. At this time, Old World climbing fern has been a problem for many years in central and south Florida, but it is moving north. The northern edge of its advance is now near Jacksonville. Both ferns reproduce readily by wind-blown spores. Animals, equipment, and even people that move through an area with climbing fern are very likely to pick up spores and move them to other locations on the property or even to other properties. Both plants are listed as Category I on the FLEPPC list.

Credit: Vic Ramey, UF/IFAS

Control

Adequate control of both climbing ferns has been achieved with multiple applications of glyphosate. Old World climbing fern is controlled with broadcast applications of Escort, to which grasses and some other native plants are tolerant. As with most invasive plants, repeated treatments may be necessary. Spot treatments of triclopyr are also effective for Old World climbing fern. However, triclopyr is highly injurious to many shrubs and trees. See Table 7.

Grasses

Cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica)

Credit: Ann Murray, UF/IFAS

Cogongrass is a fast-growing, rhizomatous (spreading with underground stem), perennial grass that has become one of the most troublesome weeds in the world. It was accidentally introduced from Japan as packing material in Mobile, Alabama in 1911. It was later intentionally introduced from the Philippines into Mississippi as forage. The Mississippi population was shared with the University of Florida, USDA Plant Introduction Station, and Soil Conservation Service in 1937 for forage and soil stabilization. It has proved to be an excellent soil stabilizer, but it is extremely difficult to prevent its escape into unintended areas. It spreads predominantly by transported rhizomes in soil. Cogongrass is listed as a noxious weed by FDACS and USDA, and it is ranked among the 10 most invasive weeds in the world.

Credit: FDEP

Control

Recommendations to control cogongrass are to treat these infestations in the late summer and early fall. Glyphosate, imazapyr, and combinations of the two herbicides are most effective, but eradication requires multiple applications (Minogue et al. 2018). Because of the extensive rhizomes of cogongrass, repeated applications of herbicide are always necessary to obtain eradication. Remember to thoroughly wet the plants with the herbicide mixture when they are green and growing, not during droughts or time of plant stress. For all recommendations, retreat as necessary. See Table 8.

Bahiagrass (Paspalum notatum), Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), Giant Fescue (Festuca arundinacea), and Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense)

These grasses have been widely established for livestock forage, but they can present problems for forest landowners wanting to establish pine stands and/or restore native groundcover on sites where the invasive grasses dominate. Introduced as improved pasture grasses from the Mediterranean region of Europe and Africa, they are now distributed worldwide.

Control

Adequate control of these grasses can be achieved with a summer application of Accord XRT followed by a spring application of an Arsenal AC and Oust® (sulfometuron) tank mix. Metsulfuron is also highly effective on bahiagrass. See Table 9.

Conclusion

The invasive species described in this publication represent those most likely to be found in forestlands in north Florida. More complete information on these and other non-native plants can be found in Langeland and Burks's Identification and Biology of Non-native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas (1998) and Langeland and Stocker's Control of Non-native plants in Natural Areas of Florida (1997). Another good source of information on invasive plants can be found in Miller's Non-native Invasive Plants of Southern Forests (2012).Other resources, including several on the web are listed below.

Learn to identify these invasive plants, and if they show up on your property treat them quickly before they can spread and increase the difficulty of controlling them. Treated areas should be periodically examined to determine if retreatment is necessary. It is normal for areas infested with invasive plants to receive multiple treatments to effectively reduce the impact and presence of these plants. The UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants is a good place to find images and more information about these and many other species: https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu.

References

Center, T. D., W. A. Overholt, E. Rohrig and M. Rayamajhi. 2015. Classical Biological Control of Air Potato in Florida. ENY-864. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in957

Croxton, M. D., M. A. Andreu, D. A. Williams, W. A. Overholt, and J. A. Smith. 2011. "Geographic origins and genetic diversity of air-potato (Dioscorea bulbifera) in Florida." Invasive Plant Science and Management 4: 22–30.

Jacono, C. C., and C. P. Boydstun. 1998. Proceedings of the Workshop on Databases for Nonindigenous Plants, Gainesville, FL, September 24–25, 1997.

Jose, S., J. Cox, D. L. Miller, D. G. Shilling, and S. Merritt. 2002. "Alien plant invasions: The story of cogongrass in southeastern forests." Journal of Forestry. 100(1): 41–44.

Kline, W .N. and J. G. Duquesnel. 1996. "Management of invasive exotics with herbicides in Florida." Down to Earth. 51(2):22–28.

Langeland, K. A. and K. C. Burks. 2022. Identification and Biology of Non-native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas, Second Ed. Pub. No. 257. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. http://ifasbooks.ifas.ufl.edu/p-197-identification-and-biology-of-non-native-plants-in-floridas-natural-areas.aspx

Langeland, K. A. and R. K. Stocker. 2022. Control of Non-native Plants in Natural Areas of Florida. SP 242. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/WG209

Langeland, K. A. 2022. Help Protect Florida's Natural Areas from Non-native Invasive Plants. Circular 1204. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AG108

Miller, J. H., S. T. Manning, and S. F. Enloe. 2013. "A management guide for invasive plants in forests." USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station General Technical Report SRS-131.

Miller, J. H. 2003. Non-native Invasive Plants of Southern Forests: A Field Guide for Identification and Control. Asheville, NC: USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, General Technical Report SRS-62.

Miller, J. H. 1999. "Controlling exotic plants in your forest." Forest Landowner 58(2): 60–64.

Minogue, P.J., B.V. Brodbeck, and J.H. Miller. 2022. Biology and management of cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica) in Southern Forests. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FR411

Muller, R. 1998. "Invasion ecology: the successful colonization of plant communities by exotic species." Natural Resources Newsletter. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Cooperative Extension Service

Osiecka, A., and P. J. Minogue. 2020. Forest Herbicide Characteristics. FOR283. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FR345

Osiecka, A., and P. J. Minogue. 2021. Considerations for Developing Effective Herbicide Prescriptions for Forest Vegetation Management. FOR273. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FR335

Ferrell, J., K. Langeland, and B. Sellers. 2019. Herbicide Application Techniques for Woody Plant Control. SS-AGR-260. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AG245

Sellers, B. A., J. A. Ferrell, G. E. MacDonald, K. A. Langeland, and S. L. Flory. 2018. Cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica) Biology, Ecology, and Management in Florida Grazing Lands. SS-AGR-52. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/WG202

Southeast Exotic Pest Plant Council. n.d. https://www.se-eppc.org/manual/index.html (Accessed August 2016)

Stone, Deborah, and Michael Andreu. “Fire and Invasive Plant Interactions” University of Florida IFAS Extension FOR 386 (2022) 13 pp. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FR457

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. n.d. "Dioscorea bulbifera." https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/dioscorea-bulbifera/ (Accessed December 2022)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service the cost of invasive species - akleg.gov. (n.d.). Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://www.akleg.gov/basis/get_documents.asp?docid=1855

WUSF Public Media - WUSF 89.7 | By Kerry Sheridan. (2022, January 4). Invasive species cost the US $21 billion per year, study finds. WUSF Public Media. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://wusfnews.wusf.usf.edu/local-state/2022-01-04/invasive-species-cost-the-us-21-billion-per-year-study-finds

Web Resources

Cogongrass.org, https://www.cogongrass.org

Invasive and Exotic Species of North America, https://www.invasive.org

The Plant Conservation Alliance's Alien Plant Working Group. Weeds Gone Wild: Alien Plant Invaders of Natural Areas, https://www.nps.gov/plants/alien/index.htm

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, https://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/