The Problem

The Need for Natural Areas

More than one-half of Florida's land area is in agricultural or urban land uses, and native habitats are continually being lost. Continued urbanization is an inevitable consequence of increasing population, and food production by agriculture is essential. However, preserving and protecting Florida's native habitats for historical significance and to protect native species, water quality, and water quantity is also essential. Natural areas have been designated on federal, state, county, city, and private lands (Figure 1).

Weeds in Natural Areas

Weeds are undesirable plants. Homeowners battle weeds in their lawns, gardens, and ponds. Weeds are considered unsightly in parks and playgrounds. Weeds interfere with transportation and can cause hazardous conditions along highways, railroads, and waterways. Foresters control weeds to enhance the growth of commercial forests. Billions of dollars are spent annually to manage weeds.

Non-native plants include species that do not occur naturally in a specified geographic area. For Florida, many non-native plants have been introduced both intentionally and unintentionally. A small percentage of those have become invasive, which is defined as “A species that is nonnative to a specified geographic area, was introduced by humans (intentionally or unintentionally), and does or can cause environmental or economic harm or harm to humans" (see FOR-370, Standardized Invasive Species Terminology for Effective Outreach Education for more information on invasive species definitions). Some common impacts of invasive plants in Florida include displacement of native plants and associated wildlife including endangered species, and alteration of natural processes such as fire and water flow.

Before the term “invasive” became commonly used, naturalists recognized potential problems with some non-native plants many years ago. In 1920 Charles Torrey Simpson, Florida's pioneer naturalist, wrote, "There are the adventive plants, the wanderers, of which we have, as yet, comparatively few species; but later, when the country is older and more generally cultivated, there will surely be an army of them." As predicted, problems associated with non-native plants becoming invasive have increased through the years and non-native invasive plants are now a growing concern to scientists and land managers. Thirty-one percent (about 1,499) of the plant species growing on their own without cultivation in Florida are non-native (Wunderlin and Hansen 2018), and some of these have become serious problems for land managers. For example, from 1997 to 2014, over $129 million was spent spent by State of Florida agencies to control invasive plant species in upland habitats alone.

Regulated Plants

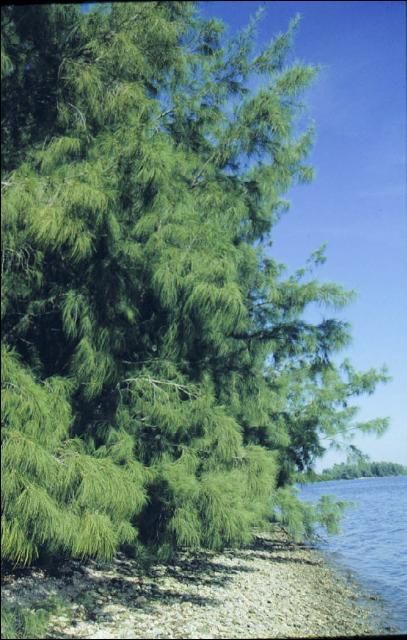

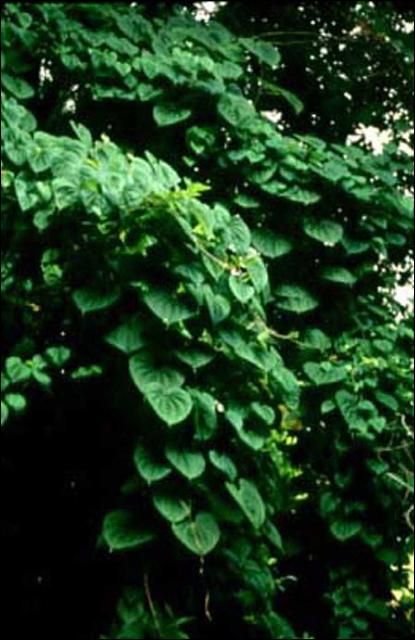

Federal and state laws were passed beginning in the 1970s to prevent further spread or importation of weeds that pose an economic threat to agriculture and navigation. These laws now restrict possession, transport, or sale of certain plants known to interfere with agroecosystems, native ecosystems, the management of ecosystems, or cause injury to public health. Weeds are listed in the United States Department of Agriculture's (USDA) Federal Noxious Weed List (see USDA Plants Database), and the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services' (FDACS) Florida Noxious Weed List. Plants that occur on these lists and may occur on private property in Florida include cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica, Figure 2), Brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolia, Figure 3), Australian pine (Casuarina spp., Figure 4), tropical soda apple (Solanum viarum, Figure 5), catclaw mimosa (Mimosa pigra, Figure 6), Australian paperbark (Melaleuca quinquinervia, Figure 7), Chinese tallow (Sapium sebiferum, Figure 8), Old World climbing fern (Lygodium microphyllum, Figure 9), carrotwood (Cupaniopsis anacardioides, Figure 10), air potato (Dioscorea bulbifera, Figure 11), and skunk vine (Paederia foetida, Figure 12). In addition to plants that are regulated at the federal and state levels, many Florida counties and cities have ordinances that prohibit planting or require removal of non-native plant species.

Credit: Jeff Mullahey

Florida Invasive Species Council List of Non-native Invasive Species

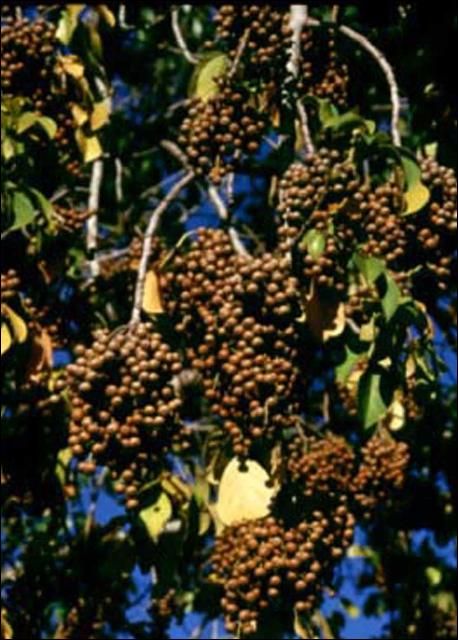

The Florida Invasive Species Council (FISC), formerly the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council), has listed species considered to be most invasive or potentially invasive in Florida. Category I plants on this list are considered to be invasive plants that are currently disrupting native plant communities in certain areas or throughout the state. Category II plants have the potential to disrupt native plant communities. While many plants on this list are also included on prohibited lists, the FISC list itself does not carry statutory authority. Examples of FISC Category I plants (in addition to the ones already listed as prohibited) include earleaf acacia (Acacia auriculiformis, Figure 13), bischofia (Bischofia javanica, Figure 14), and Chinaberry (Melia azedarach, Figure 15). The FISC list is modified as merited by new observations. Current and past FISC Invasive Plant Lists are available on the FISC website (Florida Invasive Species Council).

In Our Own Back Yards

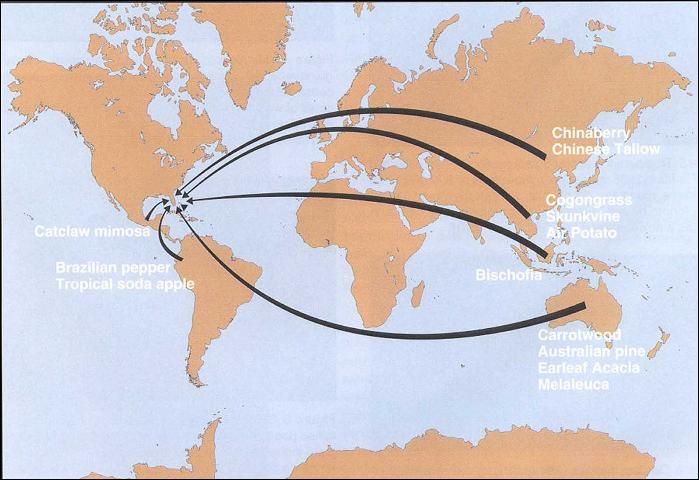

Non-native plants have been introduced as landscape ornamentals, aquarium plantings, agricultural crops, and by accident (Figure 16). They now exist in our landscapes, and some are still sold commercially. Invasive non-native plants growing in proximity to natural areas are a source of invasion. Seeds and spores can be spread by birds, animals, wind, and yard trimmings. The UF/IFAS Assessment of Non-Native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas was developed by a sub-committee of the interdepartmental UF/IFAS Invasive Plants Working Group. The purpose of the UF/IFAS assessment is to determine the invasiveness (or potential) of plant species that are recommended for uses such as landscaping and to provide UF/IFAS personnel with guidelines when making recommendations for the use of non-native plants species. Conclusions of the UF/IFAS Assessment for many species can be found at: https://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu/. These conclusions can be used as guidelines by homeowners when selecting plants for landscaping.

What Can We Do?

Learn to Recognize Florida's Non-native Invasive Plants

Not everyone will want to learn to identify the entire list of invasive plants in Florida—at least not right away. A good start is to identify plants on your own property or plants sold in local nurseries, and determine if any are considered invasive. Most invasive plants are included in various plant identification field guides, horticultural books, and botanical keys. Your local UF/IFAS Extension office can assist with plant identification. A handbook, SP 257 Identification and Biology of Non-Native Plants in Florida's Natural Areas Second Edition, is available for sale from the UF/IFAS Extension Bookstore at https://ifasbooks.ifas.ufl.edu/ [Ph: (352) 392-1764].

Prevention

When landscaping, do not use plants that have potential to be invasive in natural areas. Local land managers, park biologists, and county governments can provide information on invasive plants that are the greatest problem locally. At the University of Florida, long-range planning policy prohibits the use of many invasive species for future landscaping of its properties, and the University of Florida uses the UF/IFAS Assessment and FISC "Category I" plant list as a guideline.

Remove Non-native Invasive Plants from Your Property

Removing non-native invasive plants from private property can eliminate a major source of invasion into natural areas. Many invasive plants, such as skunk vine, are also weeds in private landscapes. Others, such as carrotwood, may serve a function in the private landscape (as a shade tree, for example). Removal of these plants may seem like a sacrifice for the property owner, but this loss can be a short-term problem. The plant removal will be of long-term, far-reaching benefit to Florida's natural areas.

Stumps of trees that are cut down should always be treated with an appropriate herbicide to prevent regrowth. After removal, invasive non-native plants can be replaced with native plants or with non-native plants that are not invasive. Information on how to control specific non-native invasive plants and suggestions for non-invasive plants to replace them with can be obtained from County Cooperative Extension offices.

Non-native invasive plants that are not removed from private property should be contained as carefully as possible, especially if the land is in proximity to sensitive natural areas. Carefully dispose of trimmed material from invasive plants, especially material with attached seeds or spores, or plant parts capable of vegetative reproduction, such as stems of oyster plant (Rhoeo spathacea). Volunteer to remove invasive plants from local natural areas under the guidance of the natural area manager. Activities such as Pepper Busting and Air Potato Roundups are often conducted for this purpose.

Learn More

The following publications provide additional information about natural areas and problems caused by non-native invasive plants in Florida and around the world:

Collard, S. B., III. 1996. Alien invaders: The continuing threat of exotic species. New York: Franklin Watts.

Cronk, Q. C. B., and J. L. Fuller. 1995. Plant invaders. London: Chapman and Hall.

Luken, J. O., and J. W. Thieret (eds.) 1997. Assessment and management of plant invasions. New York: Springer.

Randall, J. M,. and J. Marinelli. 1996. Invasive plants: Weeds of the global garden, Handbook #149. New York: Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Inc.

Simberloff, D., D.C. Schmitz, and T.C. Brown (Eds.). 1997. Strangers in paradise: Impact and management of nonspecies in Florida. Washington, D.C: Island Press.

Whitney, E., D. B. Means, and A. Rudloe. 2004. Priceless Florida: Natural Ecosystems and Native Species. Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press.

Share this Information

The effort to protect Florida's public lands from non-native invasive plants will require cooperation among private property owners, public land managers, elected officials, and others. Share this information with your neighbors to get the ball rolling and keep it rolling.

References

Wunderlin, R. P., B. F. Hansen, A. R. Franck, and F. B. Essig. 2018. Atlas of Florida Plants. [S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), USF Water Institute.] Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa. http://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/

Simpson, Charles Torrey. 1920. In Lower Florida Wilds. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 164.