Introduction

Nematodes in the family Trichodoridae (Thorne, 1935) Siddiqi, 1961, are commonly called "stubby-root" nematodes, because feeding by these nematodes can cause a stunted or "stubby" appearing root system (Figure 1). Nanidorus minor (Figure 2) is the most common species of stubby-root nematode in Florida, and in tropical and sub-tropical regions worldwide. Nanidorus minor is important because of the direct damage it causes to plant roots, and also because it can transmit certain plant viruses.

Credit: Society of Nematologists

Credit: W. T. Crow, University of Florida

Distribution

Nanidorus minor is spread around the globe, being reported in Afghanistan, Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Canary Islands, Cuba, Egypt, Fiji, Greece, India, Israel, Italy, Ivory Coast, Japan, Java, Mauritania, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Philippines, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Russia, Senegal, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, United States, Upper Volta, Venezuela, and West Germany. Within the United States it is widespread, being reported in most states.

Lifecycle and Biology

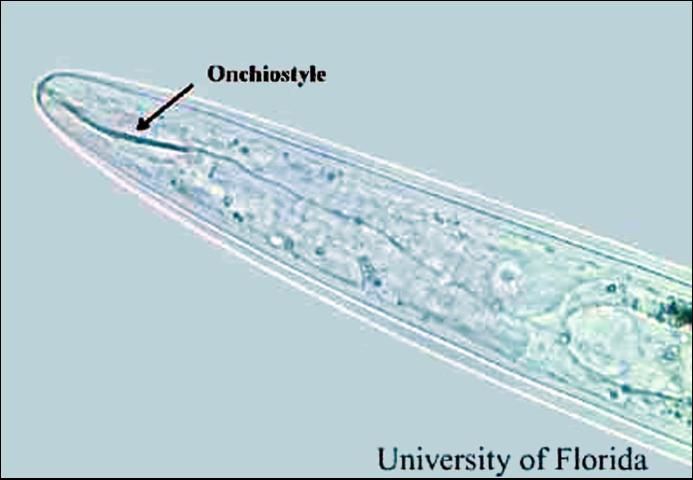

Stubby-root nematodes are very small and can be seen only with the aid of a microscope. They are ectoparasitic nematodes, meaning that they feed on plants while their bodies remain in the soil. They feed primarily on meristem cells of root tips. Stubby-root nematodes are plant-parasitic nematodes in the Triplonchida, an order of nematodes characterized by having a six-layer cuticle (body covering). Stubby-root nematodes are unique among plant-parasitic nematodes because they have an onchiostyle, a curved, solid stylet or spear that is used in feeding (Figure 3). All other plant-parasitic nematodes have straight, hollow stylets.

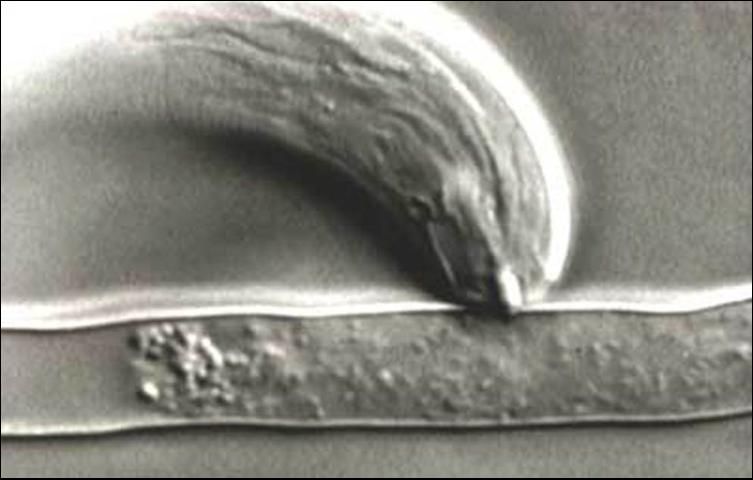

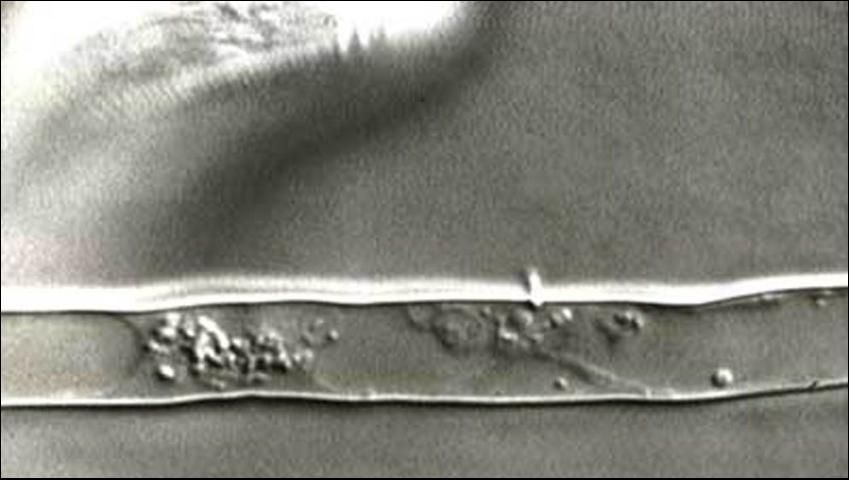

Stubby-root nematodes use their onchiostyle like a dagger to puncture holes in plant cells. The stubby root nematode then secretes from its mouth (stoma) salivary material into the punctured cell. The salivary material hardens into a feeding tube which functions as a "straw" enabling the nematode to withdraw and ingest the cell contents through the tube (Figure 4). After feeding on an individual cell, the stubby-root nematode will move on to feed on other cells, leaving old feeding tubes behind and forming new ones in each cell that it feeds from (Figure 5).

Credit: W. T. Crow, University of Florida

Credit: Urs Wyss, Institute of Phytopathology, Germany

Credit: Urs Wyss, Institute of Phytopathology, Germany

Nanidorus minor is a parthenogenic species, meaning that it reproduces without sexual activity. Most Nanidorus minor are females. Because they are not needed for reproduction, males are rare. Female lay eggs that remain in soil until they hatch as second-stage juveniles. Stubby-root nematodes are obligate plant-parasites, meaning that they must feed on plants in order to survive and reproduce. Once it locates a root and starts feeding, the juvenile nematode will molt three times before it becomes an egg-laying adult. The life cycle of Nanidorus minor is fairly short for a plant-parasite, being as short as 16 days at 84°F, but is longer at cooler temperatures.

Importance

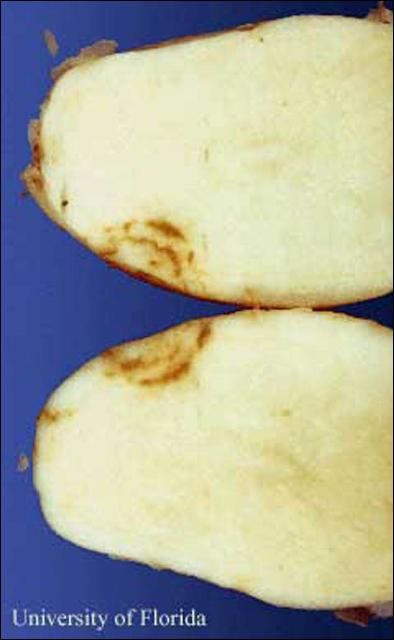

Nanidorus minor was the first ectoparasitic nematode shown to damage plants. On most hosts, feeding by Nanidorus minor on cells of root tips causes growth and elongation of roots to cease, and results in stubby-root symptoms. The damaged roots are less capable of supplying the plant with adequate water and nutrients from soil. Affected plants may exhibit the symptoms listed below and suffer yield losses. Stubby-root nematodes also are one of the few nematodes capable of transmitting plant viruses. In Florida, Nanidorus minor is the primary vector of Tobacco Rattle Virus, the cause of corky ringspot disease of potato. This is a major problem in the Hastings region of Florida. Corky ringspot causes noticeable brown rings on the surface (Figure 6) and/or brown arcs or flecking of the inside of infected potatoes (Figure 7). These symptoms make symptomatic tubers unmarketable. As few as 5% of tubers with corky ringspot symptoms can cause rejection of the entire lot of potatoes.

Credit: D. P. Weingartner, University of Florida

Credit: D. P. Weingartner, University of Florida

Symptoms

Damage caused by Nanidorus minor usually occurs in irregularly shaped patches within a given field (Figure 8). Symptoms are usually more severe in sandy than in heavier soils. Above ground symptoms include; stunting, poor stand, wilting, nutrient deficiency, and lodging. Roots may appear abbreviated or "stubby" looking (Figure 9). However, all these symptoms can be caused by other factors, so the only way to verify if Nanidorus minor is a problem is to have a nematode assay conducted by a credible nematode diagnostic lab. The University of Florida Nematode Assay Laboratory (https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/nematology-assay-lab/) provides routine diagnosis of plant-parasitic nematodes for the public at a nominal fee.

Credit: Society of Nematologists

Credit: Society of Nematologists

Hosts

Nanidorus minor has over 100 known hosts. In Florida, some of the important hosts are common grain (corn, sorghum), and turf (bermudagrass, St. Augustinegrass) grasses, vegetables (cabbage, mustard, tomato, eggplant), and agronomic crops (sugarcane, peanut, soybean).

Management

Nanidorus minor is known to occur deeper in the soil than many other plant-parasitic nematodes. In experiments, a large percentage of Nanidorus minor populations occurred between 8 to 16 inches deep, below the typical treatment zone of soil fumigants. This allows many Nanidorus minor to escape being killed by fumigant treatments. Population numbers of this nematode are known to rebound following soil fumigation to numbers higher than if no treatment were used. Therefore, soil fumigants, while effective treatments for other plant-parasitic nematodes in Florida, often are not recommended for management of Nanidorus minor.

Continuous cultivation of highly susceptible crops such as corn or sorghum can build up populations of P. minor to damaging numbers and may require the use of nematicides on subsequent crops. Summer legumes such as velvetbean or cowpea tend to keep populations of P. minor low and may reduce reliance on nematicides.

In the past, organophosphate and carbamate nematicides such as aldicarb and fenamiphos were very effective for management of Nanidorus minor. However, these nematicides have been withdrawn due to environmental and health concerns. For current nematicide recommendations go to the UF EDIS webpage at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/.

Selected References

Christie JR, Perry VG. 1951. A root disease of plants caused by a nematode of the genus Trichodorus. Science 113:491-493.

Decreamer W. 1991. Stubby root and virus vector nematodes. p.587-625 In W. R. Nickle ed. Manual of Agricultural Nematology. Macel Dekker, Inc. New York.

Hunt DJ. 1993. Aphelenchida, Longidoridae and Trichodoridae: Their systematics and bionomics. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Walkinshaw CG, Griffin GD, Larson RH. 1961. Trichodorus christiei as a vector of potato corky ringspot (tobacco rattle virus). Phytopathology 51:806-808.

Weingartner DP, Shumaker JR, Smart Jr GC. 1983. Why soil fumigation fails to control potato corky ringspot disease in Florida. Plant Disease 67: 130-134.