Credit: Kathleen Smith, Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission

Nocturnal (nighttime) habits, affinity for eerie places, and silent, darting flight have made bats the subjects of a great deal of folklore and superstition through the years. Given their ability to function in the dark when and where humans cannot, it is no wonder that bats have long been associated with the supernatural. Bats remain poorly understood even today.

Humans' general lack of understanding and appreciation of bats has contributed to alarming declines in bat populations. Some of the more important causes of these declines include destruction of habitat, use of harmful pesticides, disturbance of roost sites, proliferation of turbines used to generate wind power, and the spread of white nose syndrome. See https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw291 for more information on issues surrounding the conservation of bats in Florida.

Bats are the only mammals capable of true flight. Bats are not rodents. They are in the taxonomic order Chiroptera, which means "hand-wing." The forelimbs of bats have the same configuration as other mammals, but the bones of the fingers of bats are extremely elongated to support membranous wings. The hind limbs are also modified to allow bats to hang, head-down, by their toes without expending energy.

Most bats are highly and uniquely adapted to catch night-flying insects. Nocturnal bats locate their food and navigate by uttering ultrasonic cries that return as echoes off solid objects. The large ears and oddly shaped nose and facial configurations of some bats assist in detecting these echoes. This form of navigation is termed "echolocation." This technique is also used by dolphins to detect prey and navigate in conditions of low visibility. Once bats detect prey, they use their wings, the wing membrane surrounding their tails, and their mouths to catch insects in flight or to pick them off vegetation. Although most bats are insect eaters, some bats specialize in eating other items such as fruit, nectar, pollen, vertebrates, and even blood. All bats resident in Florida eat insects, but a few of the species that occasionally show up in south Florida feed on fruit, nectar, and pollen.

All the bats of Florida rest during daylight hours, taking shelter in a variety of places such as caves, mines, buildings, bridges, culverts, rock crevices, under tree bark, and amongst foliage. Many species congregate in nursery colonies during the spring and disperse in July and August. The crowding of many bats into a nursery colony during spring and summer raises the temperature of the roost to more than 100°F. Because young bats have no fur, they need warm and humid conditions to survive.

Most bat species in Florida produce one offspring per year, although several species produce litters of two to four pups. Species that roost in caves, buildings, and tree hollows tend to be gregarious and have only one pup at a time. Foliage-roosting species tend to be solitary and have more than one pup at a time. Foliage-roosters often possess thicker and more colorful fur than colony-roosting bats. Like other mammals, all young bats are fed milk from their mothers until they are capable of foraging on their own.

Bats are an important part of natural ecosystems. They prey upon insects, some of which are agricultural or human pests. For example, the Brazilian free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis) consumes several species of moths that are agricultural pests, such as the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda), cabbage looper (Trichoplusia ni), tobacco budworm (Heliothis virescens), and corn earworm or cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa zea). The Brazilian free-tailed bat is common throughout Florida and typically lives in very large congregations. Recent research in south Georgia has demonstrated that these bats consume many of the insect pests that afflict pecan groves, suggesting that bats may play a role in integrated pest management (IPM) planning on pecan farms. (See https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw289 for more information on the role of bats in pest management.) Bats also create nutrient-rich guano (feces) that acts as a fertilizer, supporting ground-dwelling life beneath roosts in caves and improving soil quality wherever bats defecate. Bats are important animals in scientific research, providing insights into such diverse topics as hibernation, sonar, and blood clotting.

This document describes the species of bats that occur in Florida and provides simple tips for their identification. Many bat species look very similar and cannot be definitively identified without holding the bat in hand and taking measurements of various body parts. Please note that wild animals should never be pet, touched, or captured without proper training and permits from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Photos of all species can be found at the Bat Conservation International website (http://www.batcon.org/).

Identification of Florida Bats

Thirteen species of bats live in Florida year-round (Tables 1 and 2; Bats of Florida poster). Three other species occasionally occur along the northern border of the state (Indiana myotis—Myotis sodalis, northern long-eared myotis—Myotis septentrionalis, and silver-haired bat—Lasionycteris noctivagans), and four others occasionally occur in south Florida (buffy flower bat—Erophylla sezekorni, Cuban flower bat—Phyllponysteris poeyi, Jamaican fruit-eating bat—Artibeus jamaicensis, and Cuban fig-eating bat—Phyllops falcatus). These twenty species represent 3 families. Family Vespertilionidae (twilight bats) are the best represented with 13 species, whereas three species are present from family Molossidae (free-tailed bats), and four species from family Phyllostomidae (New World leaf-nosed bats).

All twilight and free-tailed bats that occur in eastern North America are insect eaters and can be divided into two groups: those that spend at least a portion of the year in caves (Table 1) and those that roost in other types of structures (Table 2). When caves and trees are scarce, bats may roost in man-made structures such as buildings, culverts, bridges, or bat houses.

Historically, caves provided safe environments with stable temperatures ideal for bat colonies. Because cave-roosting bats may congregate in large numbers (hundreds of thousands) and because cave habitats suitable for bats are limited in number, cave-dependent bat species are extremely vulnerable to human disturbance. Human disturbance, such as that caused by recreational caving activities, stresses bats and causes them to waste valuable energy, which may result in abandonment and mortality of young. Destruction of suitable cave habitat through vandalism, commercialization, flooding by reservoirs, and other causes has resulted in population declines to the point that several species face the threat of extinction. The need for cave conservation and protection of bat colonies (natural and urban) from human disturbance is critical for the continued survival of these fascinating animals.

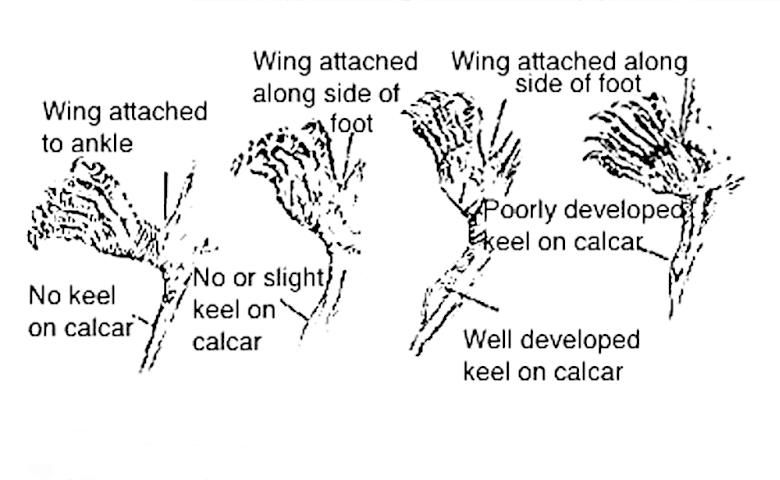

Knowledge of the roost site preferences coupled with the physical characteristics of each species can help in distinguishing among species of bats (Tables 1 and 2). The three species of free-tailed bats are the only bats with tails that extend well beyond the tail membrane, resembling the tail of a mouse. The four species of leaf-nosed bats are the only bats with a fleshy flap or noseleaf on the snout. Other characteristics important to the identification of Florida bats include the color of fur on the back (including whether or not the color changes from the base to the tip of each hair), shape of the fleshy part of the ear (the tragus), position of attachment of the tail membrane, length of hairs on the toes, and the presence or absence of a fleshy keel on the calcar (a cartilaginous structure on the rear edge of the tail membrane—see Figure 2).

Credit: Used with permission from Missouri Conservation Commission.

Additional Information

See the Bats topic page (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/topic_bats) on EDIS for more UF/IFAS bat-related fact sheets.

Websites

Bat Conservation International, Austin, TX—http://www.batcon.org/

Florida Bat Conservancy, Bay Pines, FL—http://floridabats.org

Lubee Bat Conservancy, Gainesville, FL—http://www.lubee.org/

Literature

Brown, L. N. 1997. Mammals of Florida. Miami, FL: Windward Publishing Inc.

FWC. 1999. Checklist of Florida's Mammals. Tallahassee, FL: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Kern, W. H. 2005. Bats in Buildings. ENY268. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/l/IR00003396/00001

Marks, C. S., and G. E. Marks. 2006. Bats of Florida. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Mazotti, F., and H. K. Ober. 2008. Conservation of Bats in Florida. MG342. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw291

Ober, H. K. 2008. Insect Pest Management Services Provided by Bats. WEC247. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw289

Ober, H. K. 2008. Effective Bat Houses for Florida. WEC246. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw290

Whitaker, J.O. Jr., 1998. Mammals of the Eastern United States. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.