Are you trying to incorporate ecofriendly practices into your own life, and striving to learn more ways you can make a difference? Is there something you believe your community could be doing to be more environmentally responsible? Maybe your local recycling program is going well, but you are interested in further reducing household wastes. Perhaps you are concerned with the way some hazardous waste are being disposed of by your neighbors. Is the local park cluttered with litter? Are you seeing more and more cars drive by and less and less people walking or riding bikes? Or perhaps you have been bothered by neighbors that seem to be watering the sidewalks or houses that seem to leave all the lights on.

If this relates to you, then you can become a "block leader" in your community! A block leader is any member of a community that is willing to become active and set the example for neighbors. Block leaders are the core of Community-Based Social Marketing. The goal of this article is to provide information and strategies for motivated homeowners to engage their neighbors to address local environmental issues.

What Is Community-Based Social Marketing?

Sometimes we can think of many good reasons for change, but the information alone is still not enough to cause it. Community-Based Social Marketing (CBSM) is a program that goes beyond education. It makes behavior change easier by identifying and removing the barriers to change as well as identifying and enhancing the benefits. This is done by using a variety of social marketing tools that will be explained here.

Credit: US Bureau of Reclamation, 2006

There Are Eight Steps to an Effective CBSM Program:

Step 1: Identify the behavior you wish to change

You will be most successful in changing a behavior when you are as specific as possible in identifying and focusing on one behavior at a time. Often a CBSM program will be able to change more than one behavior, but the barriers and benefits can be very different for each one. Different CBSM tools will often be more useful at changing different behaviors. It may be a good idea to start with one behavior change for your first CBSM program. As you become more comfortable with it, designing more complex campaigns will be much easier. For now, you must decide what specific behavior you would like to change. This is the first step. Do you want to see more neighbors composting? Less neighbors contaminating their recyclables? More neighbors using alternative transportation? Less neighbors wasting water on lawn care?

Step 2: Research the barriers and benefits to the change

You probably are not the first citizen to become concerned about the issue that is inspiring you to take action. In fact, CBSM has been used by many other people to make a change in their own community. Learning from their successes and failures will prevent you from reinventing the process or having the same pitfalls. Once you have chosen the behavior change you would like to see, it is time to do research on the barriers and benefits that other people have found. There are many research studies that can assist you with this part of your research, and a large collection of them can be found at www.cbsm.com. These case studies cover programs working on the following topics: water and energy efficiency, hazardous waste disposal, waste and litter reduction, pollution prevention, alternative transportation, watershed protection, composting, and the reducing, reusing and recycling of various materials.

Step 3: Choose the social marketing tool(s) you will use

You have done enough research to know what stops people from engaging in a behavior, and also what motivates them to engage in it even when there are some barriers. You are now ready to choose the CBSM tool(s) you will use. These tools can reduce the barriers and enhance the benefits you found through your research. Here are some details on the tools you can use:

Posting Reminders

Sometimes the only barrier that a person has to engaging in an ecofriendly behavior is that they simply forget! You can use prompts in your community to remove this barrier. Prompts only work in changing behavior if people are already willing to do so, and just need a reminder. An example of this may be getting people to inflate their tires properly. If a tire gauge is available at a gas station and instructions are clear, a motorist might be willing to do it if reminded. An example of a poster placed on gas pumps in this very situation is shown in Figure 2.

Credit: Lura Consulting and McKenzie-Mohr and Associates, 2002

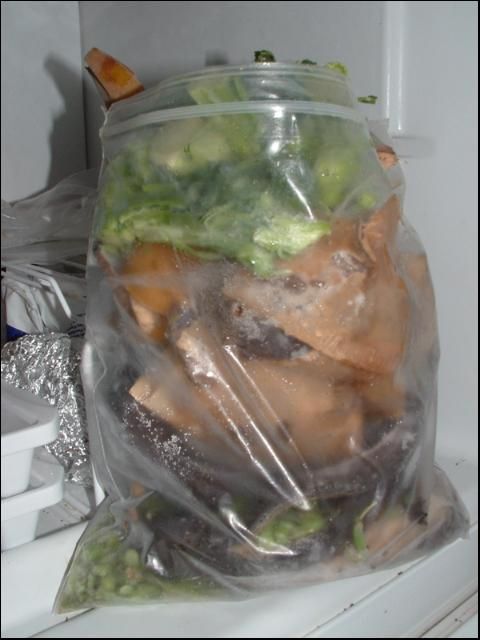

Enhancing Convenience

Many times, the biggest barrier to behavior change is the feeling that it may be inconvenient. When people are busy, this can make or break their decision to be more ecofriendly. If your research shows that inconvenience is a barrier, you need to find a way to make the change more convenient. For example, people may know the benefits to composting organic wastes; less garbage, better smelling garbage, not to mention free, natural fertilizer for the garden! They may also know how to compost properly. However, bringing their organic wastes outside to the bin every time they peel a potato or need to dump coffee grinds may be too inconvenient for them to compost regularly. People may also worry about odor if you suggest an indoor place to store organics temporarily. But what if they are taught an odorless way to reduce trips to the bin? For example, by storing their organic wastes in the freezer in a re-sealable freezer bag, they will reduce odor and trips to the bin. This could be enough to get them composting regularly. A picture of such a temporary spot in the freezer can be seen in Figure 3.

Credit: Krystal Noiseux, 2007

Providing Incentives

Isn't attending a meeting a bit more appealing when a tasty free lunch is provided? Sure! Isn't it easier to work out when you can focus on how good it makes you feel afterwards? Of course it is! The free lunch is an example of an external incentive. The positive post-workout feeling is an internal one. Both external and internal incentives can be used in CBSM programs. Direct incentives, when there is a physical return, are a great tool to encourage behavior change. Most direct incentives will need to be lasting ones. If they are only given once, there is a high chance that the behavior will only be displayed once as well. For example, if you had enough money to pay every child in your neighborhood $10 a week to stop littering for a month, you would probably be successful in reducing litter for a month! This type of incentive would be very effective in the case of a one-time behavior change, such as collecting all the litter in the neighborhood. Providing neighborhood children with $10 or a free pass to the zoo in this case could get the job done. The best thing we can do however is find a way to create a lasting internal incentive. If people are taught the connection between clean neighborhoods and clean resources, and are taught to take pride in a clean community, this may create an internal incentive to make the behavior last a long time. Shown in Figure 4 is a poster displayed giving residents positive feedback on their recycling accomplishments, creating an internal incentive to keep up the good work!

Credit: Lura Consulting, 1993

Getting Commitment

We have all had those days where we lack the motivation to get an errand done or attend a function. Still, we go through with the plan because we know we told someone that we would. The small, but vital role that commitment has on human behavior is well supported by research. We are much more likely to do something when we have committed to doing so. You can incorporate our tendency to keep promises into your CBSM program. After removing any other barriers, getting your neighbors to pledge change can mean success for your program. Verbal commitment can be helpful, but written commitment may be more binding. Also, making the commitment public gives people extra motivation to do what they said they would. An example of using commitment to foster an ecofriendly behavior would be a neighborhood petition to reduce water usage. You can get your neighbors to start with a small reduction pledge, like 10% less water usage for the month. You can then make those pledges public by printing the names in a community newsletter. This can also lay the foundation to ask neighbors to increase their pledge by small increments in the months ahead!

Communicating Effectively

Different people may engage in the same ecofriendly behaviors for very different reasons. Creating messages that appeal to a wide audience is very important. Messages should be specific, captivating, credible, and easy to remember. Suppose you have noticed some neighbors renovating their homes. You feel ecofriendly renovating would be a great community activity. Getting the greatest number of neighbors interested will be more effective if your message goes beyond environmental benefits alone. Many studies show the environmental benefits of ecofriendly renovations, but many also show the health and financial benefits. Using environmental, health, and economic benefits to promote your program can get more people involved. Examples of these three angles being used to encourage installation of ecofriendly appliances and devices are shown in Figure 5. These banners are hung in a model ecofriendly home at Lakewood Ranch in Bradenton, Florida.

Credit: Krystal Noiseux, 2005

Making it "Normal"

We are creatures of habit. We learn many of our behaviors by imitating others, and many times find it easiest to just "go with the flow." Any time we try to create change, we come up against a natural resistance to it, simply because it is not how things have been done in the past. There is no real way to get over this barrier without actually changing what is considered "normal." This process may take some time, but once something becomes "the norm" that barrier will disappear. Take the example of recycling. There was a time, not long ago, when recycling was only done commercially and in very few communities in the United States. Recycling has become widespread in many communities now, so much so that not recycling when there is a program in place is frowned upon. The spread of recycling probably owes much of its success to the fact that the act itself is highly visible. Come garbage day, it is not hard to tell which of your neighbors is or is not recycling. Increasing the visibility of other ecofriendly behaviors in your community is one tool used to change community norms.

Let's go back to the example of composting, something that your neighbors probably can't see that you do just by looking at your yard. Even the best block leader can't make it to every door to provide composting bins and teach everyone the freezer trick. However, each member of the community has the ability to reach out to one's neighbors. If everyone's composting behaviors were more visible, then composting may be as common and as normal as recycling. One easy way to make this happen is to provide your neighbors with stickers for their recycling bins along with their composting instructions. This way, when they do begin to compost they can let their neighbors know. A sticker like the one in Figure 6 on a recycling bin in front of a house may be just what you need to get the composting conversation going and to create a composting norm in your neighborhood.

Credit: Lura Consulting, 1995

Step 4: Develop your program

After completing the first three steps, you are ready to create your own program. Once you have designed your program and any materials that you will be using, it is important to make sure that you are on the right track. This can be done by getting feedback from others in the community. The best way to do this is to hold a focus group. These are small gatherings of between 6–8 people where you present your ideas and facilitate a discussion around them to identify strengths and weaknesses in your plan. Incorporating the suggestions you receive from this group brings your program one step closer to implementation.

Step 5: Pilot test your program

Before you implement your program on a large scale, you can save a lot of time and resources by first trying it out on a smaller group. This trial is called a pilot test. It can be very helpful in working out any kinks before your program is up and running. The best way to do this is to randomly select addresses, or if it is necessary randomly select streets to be a part of the pilot test.

You must find out how many people in your group are already engaging in the ecofriendly behavior (or the non-friendly one). This can be tricky. For example, to measure recycling participation, you can make note of who is placing bins out on garbage day. To measure whose grass is kept at the suggested length for water conservation, you may need to hold a measuring stick to the sidewalk on the edge of front lawns. Still, some behaviors will be impossible to measure without asking people. Some examples of this would be composting, or using Compact Fluorescent Light bulbs (CFLs). You can get this information by doing a phone, mail or face-to-face survey of the pilot group members.

Once you know how many people are engaging in your behavior before getting the program, this test group must be divided into two. One group will get the program and one will not. This will increase the chance that any change in behavior you see will be a result of your program. It is very important when you divide the pilot test group into two, that you make the two groups resemble each other as closely as possible. For example, you do not want one group to be made up mostly of families, while the other is mostly retirees. You also would not want one group of single-family homes and another of apartments. This step is important because it eliminates other reasons why you may see difference between the groups, not due to the implementation of your program.

Step 6: Make necessary changes based on your pilot

Now you have results from your pilot test. You can use them to adjust your program so it can reach its full potential. To be absolutely sure that you are implementing the full program with the best possible one you can offer, it is worth it to run another pilot with your new changes. Though you may feel you learned enough the first time not to make any mistakes again, what you do not want to do is waste any time and resources in the final program. It is better to be safe than sorry!

Step 7: Implement the full scale CBSM program

Once you have a program that is successful for your pilot test group, you are ready to deliver it on a larger scale to your community. Obtaining the same baseline information on your community's engagement in the behavior before receiving your CBSM program will give you the information you need to evaluate its success. This brings us to the final step.

Step 8: Share your story!

Researching the successes and failures of other CBSM programs helped you design yours. This means that your program can be a resource to other concerned citizens. The use of CBSM to foster eco-friendly behaviors is promising, but to be successful active citizens must network. It is important to document your CBSM program from initial planning right through full implementation. You should find a way to distribute information about your program. Give presentations to neighborhood associations. Set up interviews with local television networks. Write letters to local newspapers. Post to message boards of Internet communities. Anything to spread the word!

Generating Support for Your Program

If ecofriendly change was too easy, it wouldn't be change at all! Everyone would already be engaging in ecofriendly practices. The CBSM process requires time, patience, and attention to detail. Implementing this type of program also requires money. By now you are most likely wondering where you will get the financial support for your program. One way to get funding is to hold creative, community-building fundraising events. The proceedings from such an event can go to your program. One example might be an annual community-wide yard sale. This type of event would do more than raise funds; it would get neighbors to network which will ultimately be necessary for the success of your program. Another way to raise money is to have a portion of homeowner association dues be set aside for CBSM programs. External funding exists as well in the form of private donations or grant money from non-profit organizations. Using successful case studies from past CBSM programs (that you found through your research!) can generate support from potential funding sources. Do not be afraid to contact the authors of the reports you read on past programs and ask them for funding ideas as well!

Additional Resources

Hopefully by now you are excited about the idea of starting a CBSM program in your neighborhood. This document is a good introduction to the process, but you can find even more information in Fostering Sustainable Behavior: An Introduction to Community-Based Social Marketing by Doug McKenzie Mohr and William Smith. The authors of this book also host a website mentioned earlier (http://www.cbsm.com) that is designed to provide you with everything you need to start a CBSM program.

To learn more about Living Green issues in your neighborhood, visit the Living Green website (http://livinggreen.ifas.ufl.edu). This website contains useful information and strategies to address a wide variety of environmental issues within homes, yards, and neighborhoods. Further, 30-minute videos on a specific issue (e.g., landscaping for wildlife) can be viewed on this site. One suggestion is to order a DVD and have a viewing at your home to initiate a conversation.