What is teaweed and why would anyone want to learn more about this plant? Teaweed has been a problem plant in agriculture, but our research has found that this plant has many good qualities as a wildlife food source. Anyone interested in growing plants that benefit native wildlife, especially white-tailed deer, turkeys and quail, can improve wildlife habitat by managing native plants. How does managing native plants improve the forage quality on your property? For example, to reach optimum body size and full antler growth, white-tailed deer require at least 16% protein in the plants they consume (Cook and Gray 2003; Yarrow and Yarrow 2005). The plants discussed in this paper all meet or exceed that minimum required protein level for white-tailed deer growth and development.

Plant Characteristics

Sida acuta Burm. F., commonly referred to as teaweed, ironweed, or southern side, is an erect annual and/or perennial shrub that can grow to a height of three feet. The stems are woody, branching several times, and it has a well-developed tap root. The leaves of teaweed are lance- to rhomboid-shaped with serrated margins. Teaweed has small yellow flowers that can be solitary or growing in pairs in the leaf axils (Murphy et al. 1996). One plant can produce hundreds of seeds throughout the growing season. Teaweed or ironweed is considered a "weed" in agriculture. The plant reduces crop production, and it is not recommended for planting near agricultural fields.

Teaweed ranges from South Carolina throughout Florida and west into Mississippi (Murphy et al. 1996). The growing season starts in late spring and lasts until frost. Teaweed grows in dense stands along highways, agricultural fields, and the edges of forested lands. The seeds of teaweed disperse easily by adhering to clothing, fur, and other fibrous materials, or by moving on machinery or vehicles. Teaweed has several positive attributes that include drought resistance and adaptability to a wide variety of soil conditions. It is a native perennial plant that can tolerate heavy browsing by animals. Despite its good qualities, however, several books on wildlife management and plants beneficial to wildlife omitted mention of Sida acuta. The positive aspects of teaweed stimulated our interest in this native plant as a potential forage species. You may recognize this plant (Figure 1). Additional photos and information can be viewed at the Institute for Systematic Botany website: http://www.florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/Plant.aspx?id=2753.

Benefits of Teaweed

The real benefit of teaweed is that it can be combined with clovers to create a year long source of forage. Teaweed seeds are not readily available for purchase, but you may already have teaweed on your property and can disperse their seed. Simply expose mineral soil by raking, disking or harrowing, and broadcast the seed on the soil surface.

To study the potential forage yield and quality of a teaweed and clover mixture, we established 1-acre plots near Lottie, Alabama, and Allentown, Florida, by broadcasting 6.5 lbs teaweed seed with 25 lbs. of crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum) seed. Plots were fertilized using 100 lbs per acre of 4:12:12 (nitrogen:phosphorus:potassium) fertilizer.

An enclosure to prevent browsing was used to quantify the extent of browsing, by deer and other species, occurring outside of the enclosure. On our study sites, 2,565 lb of green weight or about 1,161 lb of dry weight per acre was consumed by browsing animals, predominately deer. Figure 1 shows the difference between browsed plants (outside the enclosure) and plants that had no browsing (inside the enclosure). Table 1 shows the growth and browse on teaweed over two years. Growth varied from 387 lb to over 5,130 lb per acre. Consumption varied as well, with browsing amounts ranging from 193 to over 1,800 lb per acre. Deer foraged between 30 and 80 percent of the teaweed, depending upon the time of year. The amount of browse varied throughout a given year and between years as well.

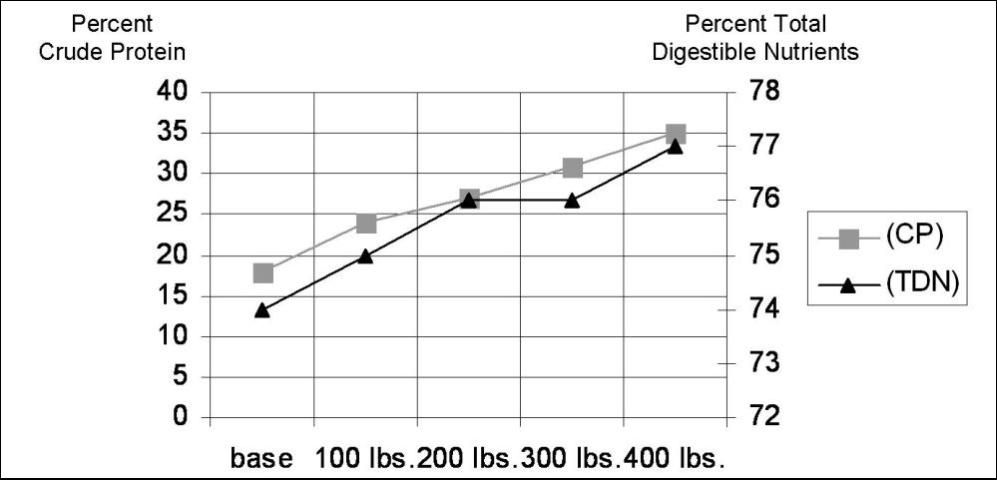

The crude protein of teaweed averaged 24.5%, with 76% total digestible nutrients. Even on areas not fertilized, teaweed had over 16% crude protein. On an additional site, teaweed plants also responded to applications of ammonium nitrate fertilizer. Each 100 pounds of ammonium nitrate fertilizer raised the crude protein content of teaweed about 3% (Figure 2). Total digestible nutrients remained about 75% at all levels of fertilization.

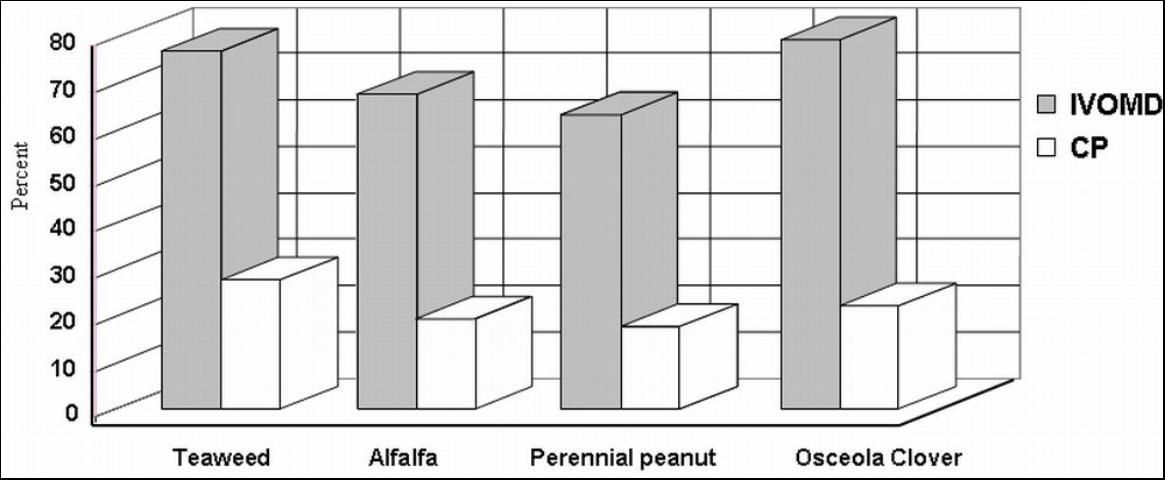

We compared the crude protein and total digestible nutrients of teaweed plants with perennial peanut, alfalfa, and Osceola clover grown at the same location (Figure 3). All of these plants had high levels of crude protein and total digestible nutrients that more than exceed the amount necessary to support white-tailed deer protein requirements (Ross 2004). Perennial peanuts and iron clay peas can be planted as warm-season forage plots. Perennial peanuts usually take a few years to become fully established on the site but once established provide very good forage for wildlife and domestic livestock as well. The areas planted with perennial peanuts can be top-seeded with clover to make a year-round food plot. Iron clay peas need to be planted annually. The clay peas can follow the fall forages that are fading in the heat of spring and summer. The clay peas and fall plantings can generate a year-round food plot providing good nutritional forage for wildlife; however, these plants require disking or harrowing to prepare the soil for sowing or planting (sprigging perennial peanuts) each year.

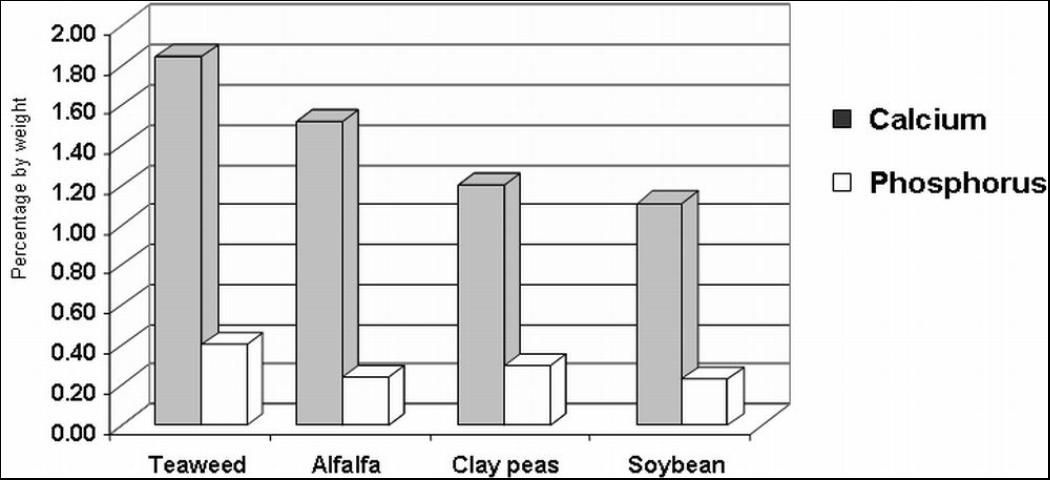

Another benefit is that teaweed has higher calcium and phosphorus content than common forages such as iron clay peas, alfalfa, and soybeans (Figure 4). Calcium and phosphorus are two of the most important minerals in a deer's diet and are necessary for bone and antler growth (Yarrow and Yarrow 1999). These minerals also are important for milk production, muscle contraction, efficient digestion, and general metabolism (Cook and Gray 2003).

Managing Teaweed

In natural areas managed for wildlife, teaweed stands should be protected and enhanced because it is a good source of nutrition. Teaweed is easy to manage and maintain compared to other forages because teaweed reseeds every year. Teaweed can be top-seeded in the fall with crimson clover to create a perennial, year-round food plot that exceeds the 16% crude protein level required for good nutrition of white-tailed deer. To maintain an area with teaweed, mow periodically or disk lightly.

What should landowners or managers do if they want to improve forages on their property?

- Determine which species of animals or birds you want to benefit.

- Talk with your county extension agent, Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission biologist, or other natural resource professionals in your area for their recommendations and suggestions.

- Find out what native plants are already in place that could be enhanced to meet your goals.

- Determine what improvements or plantings are needed to enhance your property and meet your wildlife management objectives.

Conclusions

From our work at the UF/IFAS West Florida Research and Education Center located near Jay, Florida, and several locations in southern Alabama, Sida acuta was identified as a native plant that provides food and/or cover to several species of wildlife. Some wildlife species like deer use teaweed as forage; however, other wildlife species like bobwhite quail, rabbits, and young turkeys use areas with teaweed for cover and food. Teaweed is drought tolerant, browse tolerant, native, benefits several species of wildlife, and it is perennial. Look for this on your property as an excellent wildlife food source that may already be present.

Literature Cited

Cook, C. and B. Gray. 2003. Biology and Management of White-tailed Deer in Alabama. Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries. 175 p.

Institute for Systematic Botany. 2011. Sida ulmifolia. Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants, University of South Florida. http://www.florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/Plant.aspx?id=2753 (March 2017)

Murphy, T. R., D. L. Colvin, R. Dickens, J. W. Everest, D. Hall, and L. B. McCarty. 1996. Weeds of southern turfgrasses. SP79. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. 208 p.

Ross, Matt. 2004. Seasonal protein requirements of white-tailed deer. Whitetail Stewards. 2 p.

Yarrow, G. K., and D. T. Yarrow. 1999. Managing Wildlife on Private Lands in Alabama and the Southeast. Alabama Wildlife Federation. Sweetwater Press. Birmingham, AL. 588 p.

Yarrow, G. K., and D. T. Yarrow. 2005. Managing Wildlife on Private Lands in Alabama and the Southeast edited by Dan Dumont. Alabama Wildlife Federation. Sweetwater Press. Birmingham, AL. 588 p.