Introduction

Xyleborus affinis is one of the most widespread and common ambrosia beetles in the world. It is also very common in Florida. Due to its natural attraction to freshly dead wood, the species can be a structural pest of moist timber before the wood is treated. It is also commonly assumed to be the source of tree death because of its abundance in dead or dying trees, but confirmed records of Xyleborus affinis attacking healthy trees are rare. Even in the cases where damage on healthy trees is reported, it is quite likely that the trees have been under some prior unapparent stress, such as recent excess of water.

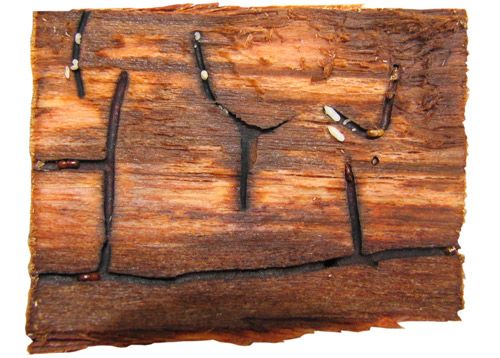

Like other ambrosia beetles, Xyleborus affinis bores tunnels (called galleries) into the xylem of weakened, cut or injured trees where a symbiotic fungus is farmed for food. Females lay eggs in the fungus-lined galleries and larvae feed exclusively on the fungi.

Credit: Jiri Hulcr, UF/IFAS

The gardens of Xyleborus affinis usually contain multiple fungus species (Kostovcik et al. 2015). Recent studies have shown that Xyleborus affinis can vector the fungus responsible for laurel wilt disease, Raffaelea lauricola T.C. Harr., Fraedrich & Aghayeva. Laurel wilt is a lethal disease of numerous species of trees in the Lauraceae family (Harrington and Fraedrich 2010; Harrington et al. 2010; Carrillo et al. 2013). In a study conducted by Carrillo et al. (2013), Xyleborus affinis carrying Raffaelea lauricola was shown to attack both redbay and avocado trees, but only transmitted laurel wilt to redbay. Because of this, Xyleborus affinis may become a more serious pest where pathogenic ambrosia fungi are a concern.

Distribution

Xyleborus affinis is native to the tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas, including Florida (Rabaglia et al. 2006; Atkinson 2014), and has recently spread to most tropical and subtropical regions in the world. Like many other wood borers, Xyleborus affinis can be easily spread through the distribution of wood in international commerce. Although it is among the most widespread and common ambrosia beetles in forested areas around the world, it is often under-reported because it is only weakly attracted to ethanol, the most commonly used lure for ambrosia beetle monitoring (Steininger et al. 2015).

In the US, Xyleborus affinisis is distributed from the east coast of the United States, from Michigan in the north, south to Florida and as far west as Texas. It is also native to South and Central America, including the Antilles, Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and Argentina. The beetle was introduced into Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, and the Pacific Islands including Hawaii (Wood 1982; Rabaglia et al. 2006).

Credit: Atkinson (2014)

Description

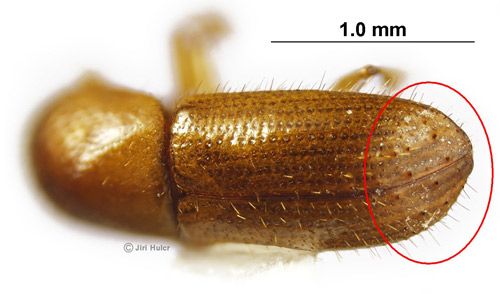

Adults: This yellowish to reddish-brown species is similar in appearance to other ambrosia beetles in the genus Xyleborus. Most Xyleborus beetles have an elongated, cylindrical body and are yellow, red or light brown in color. Adults of all Xyleborus species are sexually dimorphic, with females being larger than males. Xyleborus affinis females average 2.0–2.7 mm and males are 1.7–2.0 mm in length (Wood 1962; Bright 1968). Males are wingless, have smaller eyes and antennae, and occur in much smaller numbers. The female:male sex ratio has been reported as 8.5:1 in one study (Roeper et al. 1980), but it varies significantly.

This species is very similar to two common Xyleborus species in Florida, Xyleborus perforans Wollaston and Xyleborus volvulus Fabricius. The only reliable way to distinguish Xyleborus affinis from these two is the abdominal declivity, the broad, downward slope at the end of the elytra. In Xyleborus affinis, the surface of the declivity is dull and opaque, in the other two species it is glossy and smooth. More information on identification of Florida's ambrosia beetles can be found here: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fr389.

Credit: Jiri Hulcr, UF/IFAS

Eggs: The off-white, oblong, glossy eggs range in length from 0.6 to 1.0 mm, averaging 0.718 mm. Eggs are laid in groups of two to four along the horizontal tunnels branching away from the main vertical tunnels. In temperatures of 29°C, females have been shown to lay eggs as soon as three days after introduction into the host and up to 27 days (Roeper et al. 1980). One female can lay several dozen eggs, but the number of eggs (and hence larvae) in an individual gallery can be greater because daughters often lay eggs there as well.

Larvae: Larvae are white, legless, and slightly curved. Larvae hatch in 7–14 days at 29°C and in 14–35 days at 22–24°C. They feed exclusively on the farmed fungal symbiont that lines the galleries. There are three larval instars (Roeper et al. 1980).

Pupae: The initially white pupae turn light brown just before adult emergence and average 2.0 and 2.7 mm in length for male and female pupae, respectively. Larvae pupate for 11–23 days at 29°C and 21–35 days at 22–24° C. Adults emerge in 18-35 days at 29°C and 27–35 days at 22–24°C (Roeper et al. 1980).

Biology and Ecology

Xyleborus affinis is naturally found in moist, fallen logs on the ground of natural forests and rarely interferes with human activities. In large trees, the beetles colonize dead phloem first, followed by the xylem, where the majority of eggs are laid (Jiri Hulcr, unpublished data). The females inoculate the interior of the tunnels they create with the fungal symbiont, which is stored in a specialized pouch called the mycangium inside the beetle's mouth. Larvae feed on the fruiting bodies of the fungi until adulthood (Carrillo et al. 2013).

As in all other ambrosia beetles in the tribe Xyleborini, Xyleborus affinis is haplo-diploid and inbred. This means that females hatch from fertilized eggs with both the mother's and the father's genetic information. Males, on the other hand, only inherit their mother's genes—they never have a father. Males never leave the original host tree, and their only role in life is to fertilize the females around them, typically their sisters. Females, upon reaching adulthood, either keep reproducing in the same log if conditions permit, or fly out in search of a new host if their native log is too deteriorated (Wood 1982). The ability of Xyleborus affinis to maintain overlapping populations in the same log is unusual among ambrosia beetles because in most species each generation seeks a new host.

Credit: Jiri Hulcr, UF/IFAS

Xyleborus affinis can live in mutualistic symbiosis with several fungal species, typically in the genus Raffaelea (Kostovcik et al. 2015). As the symbiotic fungus community is diverse and not very specific, the beetle is able to acquire other fungal symbionts from other ambrosia beetles. An example is the recent acquisition of Raffaelea lauricola, a non-native pathogenic ambrosia fungus with which Xyleborus affinis did not coevolve (Carrillo et al. 2013).

Credit: Jiri Hulcr and Kyle Miller, UF/IFAS

Credit: Jiri Hulcr, UF/IFAS (taken in Peru)

Hosts

Xyleborus affinis is extremely polyphagous and has a known host range of 248 species, angiosperms as well as gymnosperms (Schedl 1962; Wood 1982).

While Xyleborus affinis is a generalist in terms of host tree, it is very selective in terms of host decay status and moisture: it preferentially colonizes larger and very moist pieces of wood that died recently. This species can reach especially high abundance in logs partially submerged in water or lying on moist ground. This is presumably to meet the moisture requirement of the symbiotic fungus.

Damage

The presence of Xyleborus affinis can hasten the decline of weak and injured trees, but normally does not cause it. Reports of this species attacking apparently healthy sugarcane and Lauraceae trees exist (Merkl and Tusnadi 1992; Granda Giro 2003; Wood 1982; Carrillo et al. 2013), but as with many ambrosia beetle damage reports, the actual health status of the trees had not been assessed.

Even though this is not an aggressive ambrosia beetle, it has recently become important from the phytosanitary perspective. This is due to the capacity of this species to vector pathogenic ambrosia fungi such as the causal agent of laurel wilt. Thus the spread of Xyleborus affinis from areas infected by this fungus may result in the transport of the pathogen to yet-uninfested regions.

Xyleborus affinis can cause structural damage to timber that is freshly cut (green timber) and has not been dried or chemically treated. Tunneling systems are found throughout the sapwood of the tree, but rarely in the heartwood. Depending on moisture conditions, trees could have numerous superficial tunnels that can be viewed upon pulling back the bark and many tunnels inside the xylem that become apparent when the wood is cut. Xyleborus affinis can cause greater timber damage than some other ambrosia beetles because of its family organization and labor division. While in most ambrosia beetles the gallery is excavated solely by the mother beetle, in Xyleborus affinis the daughter females help expand the tunnel system.

Management

Typically no active management of Xyleborus affinis is necessary, as the beetle attacks dying or dead trees. However, it can be considered a pest in two circumstances: 1) as a secondary vector of Raffaelea lauricola in avocado groves, and 2) as a structural pest in green wood (non-treated, non-dried, broadleaf species), which is a rather rare event.

Good sanitation and immediate removal of trees showing signs and symptoms of laurel wilt and the use of dried wood for structural purposes is recommended.

Selected References

Atkinson T. 2014. Bark beetles of North and Central America. http://barkbeetles.info. (1 December 2014).

Bright D E Jr. 1968. Review of the tribe Xyleborini in America north of Mexico (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). The Canadian Entomologist 100: 1288–1321.

Carrillo D, Duncan RE, Ploetz JN, Campbell AF, Ploetz RC, Pena JE. 2013. Lateral transfer of a phytopathogenic symbiont among native and exotic ambrosia beetles. Plant Pathology 63: 54–62.

Granda Giro C. 2003. Xyleborus affinis (Eichh) (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) atacando plantaciones de cana de azucar en la provincia de Santiago de Cuba. Fitosanidad 7: 61.

Harrington TC, Aghayeva DN, Fraedrich SW. 2010. New combinations in Raffaelea, Ambrosiella, and Hyalorhinocladiela, and four new species from the redbay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus. Mycotaxon 111: 337–361.

Harrington TC, Fraedrich SW. 2010. Quantification of propagules of the laurel wilt fungus and other mycangial fungi from the redbay ambrosia beetle, Xyleborus glabratus. Phytopathology 100: 1118–1123.

Kostovcik M, Bateman C, Kolarik M, Stelinski L, Jordal B, Hulcr J. 2015. The ambrosia symbiosis is specific in some species and promiscuous in others: Evidence from community pyrosequencing. The ISME Journal 9: 126–138.

Merkl O, Tusnadi CK. 1992. First introduction of Xyleborus affinis (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), a pest of Dracaena fragrans Massangeana, to Hungary. Folia Entomologica Hungarica 52: 67–72.

Rabaglia RJ, Dole SA, Cognato AL. 2006. Review of American Xyleborina (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) occurring north of Mexico, with an illustrated key. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99: 1034–1056.

Roeper RA, Treeful LM, O'Brien KM, Foote RA, Bunce MA. 1980. Life history of the ambrosia beetle Xyleborus affinis (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) from in-vitro culture. Great Lakes Entomologist 13: 141–145

Schedl KE. 1962. Scolytidae and Platypodidae Afrikas. Revista de Entomologia de Moçambique, 5: 1–1352.

Steininger MS, Hulcr J, Šigut M, Lucky A. 2015. Simple and efficient trap for bark and ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) to facilitate invasive species monitoring and citizen involvement. Journal of Economic Entomology 1-9: DOI: 10.1093/jee/tov014

Wood SL. 1982. The bark and ambrosia beetles of North and Central America (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), a taxonomic monograph. Memoirs of the Great Basin Naturalist 6: 1–1359.