The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

This grasshopper is well known in the southeastern US, and elsewhere, due to its large size and widespread use in biology classrooms for dissection exercises. Also, it can be of economic importance in Florida. It is one of a few species of grasshoppers in Florida that occurs in large enough numbers to cause serious damage to citrus, vegetable crops, and landscape ornamentals. Unfortunately, the scientific community uses two different scientific names for the same species, and R. microptera (Palisot de Beauvois) is also called R. guttata (Houttuyn). Technically, the latter is probably the correct name (Kevan 1980), but because the former designation was used for many years, this proposed 'correction' has introduced unnecessary confusion (Cohn 1999), so most scientists continue to call it R. microptera.

The eastern lubber is quite clumsy and slow in movement and mostly travels by walking and crawling feebly over the substrate. The "lubber" designation is interesting because it aptly describes this grasshopper. "Lubber" is derived from an old English word "lobre" which means lazy or clumsy. This term has come to mean a big, clumsy, and stupid person, also known as a lout or lummox. In modern times, it is normally used only by seafarers, who term novices "landlubbers". Eastern lubber is one of only four species in the family Romaleidae found north of Mexico, but there are many other species in South America (Rehn and Grant 1961), and many are winged and agile, so although some other species in this family may be called lubbers, the "lubber" designation is not appropriate for the entire family.

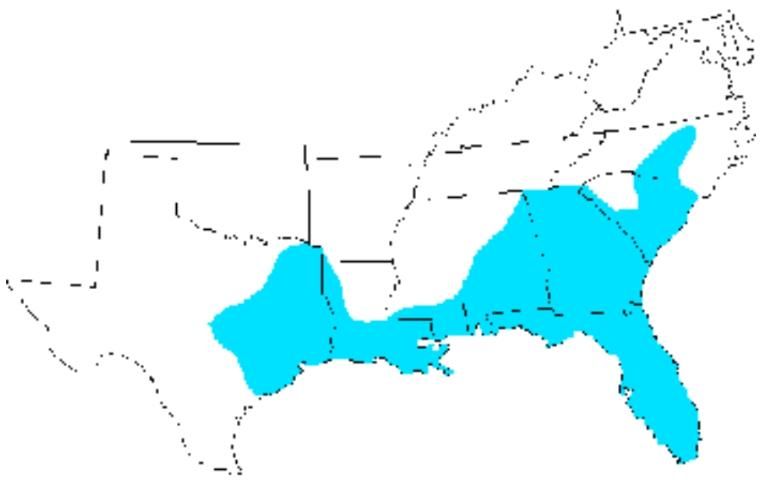

Distribution

The eastern lubber grasshopper is limited to the southeastern region of the United States. It is found from the North Carolina south through South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, and west through Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana to central Texas (Capinera et al. 2004).

Description

Eastern lubber grasshopper is surely the most distinctive grasshopper species found in the southeastern US. Adults are colorful, but the color pattern varies. Often the adult eastern lubber is mostly yellow or tawny, with black on the distal portion of the antennae, on the pronotum, and on the abdominal segments. The forewings extend two-thirds to three-fourths the length of the abdomen. The hind wings are short and incapable of providing lift for flight. The forewings tend to be pink or rose in color centrally whereas the hind wings are entirely rose in color. Darker forms of this species also exist, wherein the yellow color becomes the minor rather than the major color component, and in northern Florida a predominantly black form is sometimes found. Adults attain a large size, males measuring 43-55 mm in length and females often measuring 50-70 mm, sometimes 90 mm. Not only is this large, heavy-bodied grasshopper unable to fly, but is poor at leaping as well, so mostly it is observed walking. However, it is a good climber, and often climbs trees to feed on juvenile foliage at the tips of branches.

Both sexes stridulate (make noise) by rubbing the forewing against the hind wing. When alarmed, lubbers will spread their wings, hiss, and secrete foul-smelling froth from their spiracles. They can expel a fine spray of toxic chemicals for a distance of 15 cm. The chemical discharge from the tracheal system is believed to be an anti-predator defense, and to consist of chemicals both synthesized and sequestered from the diet. The variation in toxins assimilated from the diet make it difficult for predators to adapt to the toxins (Chapman and Joern 1990). Many vertebrate, but not invertebrate, predators are affected (Jones et al. 1987, 1989; Whitman et al. 1992). Their bright color pattern is believed to be a warning to vertebrate predators that lubbers are not palatable. Their tendency to aggregate and to climb vegetation, especially at night, is a component of their defensive behavior.

Eggs

The eggs of lubber grasshoppers are yellowish or brown in color. They are elongate elliptical in shape and measure about 9.5 mm in length and 2.5 mm in width. They are laid in neatly arranged clusters, or pods, which consist of rows of eggs positioned parallel to one another, and held together by a secretion. Normally there are 30–50 eggs in each pod. Ovipositing females are reported to prefer mixed broadleaf tree-pine habitats with intermediate soil moisture levels, avoiding both lowland, moist, compact soil and upland, dry, sandy soil (Watson 1941, Kuitert and Connin 1953). The female deposits the pod in the soil at a depth of 3–5 cm and closes the oviposition hole with a frothy secretion or plug. The plug allows the young grasshoppers easy access to the soil surface when they hatch. Egg pods tend to be clustered, with females preferentially ovipositing where eggs have already been deposited (Stauffer et al. 1998). According to Hunter-Jones (1967), females each produce 3–5 egg clusters in structures called pods. The pod is not much more than tightly packed eggs surrounded by rigid, frothy material, with most of the froth deposited at the tip of the pod closest to the surface. The froth allows an easy exit for the young hoppers as they can readily wiggle through this as they hatch. The interval between egg pod production by a female is about 2 weeks. Hunter-Jones reported egg production of 30-80 eggs per pod, averaging about 60 eggs per pod. Egg production was greater under solitary than crowded conditions. On the other hand, under field conditions Stauffer and Whitman (2007) reported egg production of 25-50 eggs per pod, with only 1–3 pods per female. Thus, egg production in the laboratory was greater than in the field. The eggs require a cool period (e.g., 20°C for 3 months) but then will hatch when exposed to warmer temperatures. Typically, egg hatch occurs in the morning.

Nymphs

The immature eastern lubber grasshopper differs dramatically in appearance from the adults (Capinera et al. 1999, 2001). Their color pattern is so different from the adult stage that the nymphs commonly are mistaken for a different species than the adult form. Nymphs (immature grasshoppers) typically are almost completely black, but with a distinctive yellow, orange, or red stripe located dorsally (though occasionally they are reddish brown). The hopper's face, edge of the pronotum, and abdominal segments also may contain reddish accents. Often the reddish accents change to yellow over the course of development. When they first molt, the young hoppers may be brownish, but they soon darken to black.

As they mature, the nymphs change slightly in appearance; the instar can be determined by examination of the developing wings. Normally there are 5 instars, though occasionally 6 instars occur. The early instars can be distinguished by a combination of body size, the number of antennal segments, and the form of the developing wings. The nymphs measure about 10–12, 16–20, 22–25, 30–40, and 35–45 mm in length during instars 1–5, respectively. Antennal segments, which can be difficult to distinguish even with magnification, number 12, 14–16, 16–18, 20, and 20 segments per antenna during instars 1–5, respectively. The shapes of the plates immediately behind the pronotum (the future wings) change slightly with each molt. During the first instar the ventral surface is broadly rounded; during the second instar the ventral edges begin to narrow slightly and point slightly posteriorly, and also acquire slight indication of venation; during the third instar the ventral edges of the plates are markedly elongate, point strongly posteriorly, and the veins are pronounced. At the molt to the fourth instar the orientation of the small, developing wings shifts from pointing downward to pointing upward and posteriorly. In instar 4 the small forewings and hind wings are discrete and do not overlap, though the forewings may be completely or partly hidden beneath the pronotum. In instar 5, the slightly larger wings overlap, appearing to be a single pair of wings. Even in the fifth instar, however, the wing buds do not cover the tympanum. In adults, however, the wings overlap and cover the tympanum, extending posteriorly to cover 3–4 abdominal segments.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: John Capinera, University of Florida

Young nymphs are highly gregarious, and remain gregarious through most of the nymphal period, though the intensity dissipates with time. Especially at night, they tend to aggregate and may climb vegetation to rest for the evening.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Life History

There is one generation per year, with the egg stage overwintering. Apparently there is not an obligatory diapause (required period of dormancy) in the egg stage; they simply have a long period of development (about 200 days) when held at low temperatures (Hunter-Jones 1967). These grasshoppers are long-lived, and either nymphs or adults are present throughout most of the year in the southern portions of Florida. In northern Florida and along the Gulf Coast they may be found from March–April to about October–November. In Florida, the highest number of adults can be observed during the months of July and August. Eggs are produced about a month after emergence of the adults. Duration of the egg stage is 6–8 months.

After mating, females will begin laying eggs during the summer months. The male usually guards the ovipositing female, sometimes for more than a day. The timing of oviposition is highly variable, but ovipositing females select open, sunny areas of higher elevation, then use the tip of the abdomen to dig a small hole into a suitable patch of soil. Usually at a shallow depth, but sometimes up to a depth of about 5 cm, she will deposit her eggs within a light foamy froth. These eggs will remain in the soil through late fall and winter and then begin hatching in spring. The young grasshoppers crawl up out of the soil upon hatching and congregate near suitable food sources. Lubbers are often found in damp or wet habitats, but seek drier sites for egg-laying.

Populations cycle up and down, possibly due to the action of parasites. The tachinid fly Anisia serotina (Reinhard) attains high levels of parasitism, sometimes 60–90% (Lamb et al. 1999). We have also found the sarcophagids Blaesoxipha opifera (Coquillett) and Blaesoxipha hunter (Hough) parasitizing this grasshopper, sometimes at high incidences of parasitism (unpublished; identified by G.A. Dahlem, Northern Kentucky University). Pathogens known from R. microptera include Boliviana floridensis (Stauffer and Whitman 2007) and Encephalitozoon romaleae (Lange et al. 2009).

Overall, the natural enemies of lubber grasshoppers are poorly documented. Vertebrate predators such as birds and lizards learn to avoid these insects due to the production of toxic secretions by the adult hoppers, though this is not absolute (Chapman and Joern 1990). Naïve vertebrates often gag, regurgitate, and sometimes die following consumption of lubbers (Yousef and Whitman 1992). However, loggerhead shrikes, Lanius ludovicianus Linnaeus, capture and cache lubbers by impaling them on thorns and the barbs of barbed wire fence. After 1–2 days the toxins degrade and the dead lubbers become edible to the shrikes (Yousef and Whitman 1992). In addition to parasitic flies, nematodes have been reported from lubbers, and it is possible to infect lubbers experimentally with the grasshopper-infecting nematode Mermis nigrescens.

Credit: John Capinera, University of Florida

Credit: John Capinera, University of Florida

Credit: John Capinera, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Habitat and Hosts

Eastern lubber grasshopper has a broad host range. At least 100 species from 38 plant families containing shrubs, herbs, broadleaf weeds, and grasses are reportedly eaten (Whitman 1988), though their mouthparts are best adapted for feeding on forbs (broad-leaf plants), not grasses (Squitier and Capinera 2002). Among the plants observed to be eaten are pokeweed, Phytolaca americana; tread-softly, Cnidoscolus stimmulosus; pickerel weed, Pontederia cordata; lizard's tail, Saururus sp.; sedge, Cyperus; and arrowhead, Sagittaria spp. Though its preferred habitat seems to be low, wet areas in pastures and woods and along ditches, lubbers disperse long distances during the nymphal period. They are gregarious and flightless, their migrations sometimes bringing large numbers into contact with crops where they damage vegetables, some field crops (peanuts, cowpeas, corn), fruit trees (citrus, figs, peach), and ornamental plants (Kuitert and Connin 1953).

The nature of polyphagous insects is to accept at least small amounts of many plants, a strategy that assures they will not starve. However, not all plants are accepted equally. For example, although lubbers display broad preference among vegetable crops, some plants such as pea, lettuce, kale, beans, and cabbage are relatively preferred whereas eggplant, tomato, pepper, celery, okra, fennel, and sweet corn are less preferred (Capinera 2014). They commonly defoliate amaryllis, Amazon lily, crinum, narcissus, and related plants (family Amaryllidaceae) in flower gardens. Among ornamental plants, they also will feed readily on oleander, butterfly weed, peregrina, Mexican petunia, and lantana (Capinera 2014). Preferred weeds include painted leaf, Poinsettia cyathophora; tread-softly, Cnidoscolus stimulosus; chamber bitter, Phyllanthus urinaria; Florida beggarweed, Desmodium tortuosum; Old-world diamond-flower, Oldenlandia corymbosa; Florida pusley, Richardia scabra; and smooth crabgrass, Digitaria ischaemum (Capinera 2014).

Damage

Lubber grasshoppers are defoliators, consuming the leaf tissue of numerous plants. They climb readily, and because they are gregarious they can completely strip foliage from plants. More commonly, however, they will eat irregular holes in vegetation and then move on to another leaf or plant. Lubber grasshoppers are not as damaging as their size might suggest; they consume less food than smaller grasshoppers (Griffiths and Thompson 1952). Damage is commonly associated with areas that support weeds or semi-aquatic plants such as irrigation and drainage ditches, and edges of ponds. Grasshoppers developing initially in such areas will disperse to crops and residential areas, where they cause damage. Thus, as is the case with many grasshoppers, monitoring and treatment of areas where nymphal development occurs is recommended to prevent damage to economically important plants. Also helpful is to keep vegetation mowed, as short vegetation is less supportive of grasshoppers.

Management

Management of these insects tends to rely on capture (physical removal) when only a few hoppers are present. When there are too many to be controlled by hand-picking, insecticides can be applied. Insecticides can be applied to the foliage or directly to the grasshopper. However, due to their large size and ability to detoxify natural toxins associated with food plants, they often prove difficult to kill, especially by spraying the foliage. Insecticides that will kill lubber grasshoppers include carbaryl, bifenthrin, cyhalothrin, permethrin, esfenvalerate, and spinosad. (Note: These are the technical names of insecticides, not the trade names; these names appear in the 'ingredients' section of the label.) Spinosad is particularly interesting because it is a biologically based, relatively safe product; unfortunately, it is rather slow acting on grasshoppers, so it may take a few days to see results of treatment. Insecticide treatment is more effective for young grasshoppers, which may necessitate scouting for hoppers in weedy areas, and treatment of them before they move into gardens and crops. An alternative is to treat the margins of cropland, perhaps the initial 1–20 meters, so that as hoppers disperse through the crop from the edges they encounter treated vegetation and perish after sampling it. Because they are dispersive, and may continue to invade an area even after it is treated with insecticide, it can be difficult to provide protection to plants without diligent monitoring and retreatment.

If insecticides are used, be sure to apply them according to the directions on the label of the container. Especially if insecticides are applied to food crops or near water, it is important to follow directions. Most of the insecticides listed above are toxic to fish.

Insecticide-containing baits are sometimes formulated for grasshopper control; normally bran is the substrate to which the insecticide is applied, and it is sprinkled on the soil surface near the plants being protected. Lubbers will accept such baits, and insects are readily killed if they ingest the toxicant and bait. However, this tactic works better when the bait is applied to the vicinity of less preferred plants, as the hoppers will tend to eat the favored host plants in preference to the treated bait (Barbara and Capinera 2003, Capinera 2014). Treatment of field margins with baits can help to reduce crop damage from immature and flightless hoppers such as lubbers, though treatment of field margins is less effective with grasshopper species that are strong fliers such as Schistocerca americana (Drury).

Credit: John Capinera, University of Florida

Selected References

Barbara, KA, Capinera JL. 2003. Development of a toxic bait for control of eastern lubber grasshopper (Orthoptera: Acrididae). Journal of Economic Entomology 96: 584–591.

Blatchley WS. 1920. Orthoptera of Northeastern America. Nature Publishing Company. Indianapolis, Indiana. pp. 304–307.

Capinera JL. 2014. Host plant selection by Romalea microptera (Orthoptera: Romaleidae). Florida Entomologist 97: 38–49.

Capinera JL, Scherer CW, Squitier JM. 1999. Grasshoppers of Florida. http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/ghopper/ghopper.html

Capinera JL, Scherer CW, Squitier JM. 2001. Grasshoppers of Florida. University Press of Florida. 143 pp.

Capinera JL, Scott RD, and Walker TJ. 2004. Field guide to the grasshoppers, katydids, and crickets of the United States. Cornell University Press, Ithaca. 249 pp.

Chapman RF, Joern A (eds.). 1990. Biology of Grasshoppers. John Wiley, New York.

Cohn TJ. 1999. Current controversies: nomenclatorial stability and the law of priority. Metaleptea 19: 8–9.

Griffiths JT, Thompson WL. 1952. Grasshoppers in citrus groves. University of Florida Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin no. 496.

Helfer JR. 1953. How to Know the Grasshoppers, Cockroaches and Their Allies. WM.C. Brown Company Publishers. Dubuque, Iowa. pp. 100–101.

Hunter-Jones, P. 1967. The life-history of the eastern lubber grasshopper, Romalea microptera (Beauvois), (Orthoptera: Acrididae) under laboratory conditions. Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society, London (A) 42: 18–24.

Johny J, Whitman DW. 2005. Description and laboratory biology of Boliviana floridensis n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Eugregarinida) parasitizing the eastern lobster grasshopper, Romalea microptera (Ortoptera: Romalidae) from Florida, USA. Comparative Parasitology 72: 150–156, doi:10.1654/4164.

Jones CG, Hess TA, Whitman DW, Silk PJ, Blum MS. 1987. Effects of diet breadth on autogenous chemical defense of a generalist grasshopper. Journal of Chemical Ecology 13: 283–297.

Jones CG, Whitman DW, Compton SJ, Silk PJ, Blum MS. 1989. Reduction in diet breadth results in sequestration of plant chemicals and increases efficacy of chemical defense in a generalist grasshopper. Journal of Chemical Ecology 15: 1811–1822.

Kevan DK McE. 1980. Romalea guttata (Houttuyn), name change for well-known "eastern lubber grasshopper" (Orthoptera: Romaleidae). Entomological News 91: 139–140.

Kuitert LC, Connin RV. 1953. Grasshoppers and their control. University of Florida Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin no. 516.

Lamb MA, Otto DJ, Whitman DW. 1999. Parasitism of eastern lubber grasshopper by Anisia serotina (Diptera: Tachinidae) in Florida. Florida Entomologist 82: 365–371.

Lange CE, Johny S, Baker MD, Whitman DW, Solter LF. 2009. A new Encephalitozoon species (Microsporidia) isolated from the lubber grasshopper, Romalea microptera (Beauvois) (Orthoptera: Romaleidae). Journal of Parasitology 95: 976–986.

Rehn JAG, Grant Jr HJ. 1961. A Monograph of the Orthoptera of North America (North of Mexico). Monographs of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. No. 12. Vol. 1. pp. 231–240. Wickersham Printing Company. Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Squitier JM, Capinera JL. 2002. Host selection by grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acrididae) inhabiting semi-aquatic environments. Florida Entomologist 85: 336–340.

Stauffer TW, Hegrenes SG, Whitman, DW. 1998. A laboratory study of oviposition site preference in the lubber grasshopper, Romalea guttata (Houttuyn). Journal of Orthoptera Research 7: 217–221.

Stauffer TW, Whitman DW. 2007. Divergent oviposition behaviors in a desert vs a marsh grasshopper. Journal of Orthoptera Research 16: 103–114.

Watson JR. 1941. Migrations and food preferences of the lubberly locust. Florida Entomologist 24: 40–42.

Whitman DW. 1988. Allelochemical interactions among plants, herbivores, and their predators, pp. 11–64. In Barbosa P and Letournearu D (eds.) Novel Aspects of Insect-Plant Interactions. J. Wiley, New York.

Whitman DW, Billen JPJ, Alsop D, Blum MS. 1991. Anatomy, ultrastructure, and functional morphology of the metathoracic tracheal defensive glands of the grasshopper Romalea guttata. Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 2100–2108.

Whitman DW, Jones CG, Blum MS. 1992. Defensive secretion in lubber grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Romalidae): influence of age, sex, diet, and discharge frequency. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 85: 96–102.

Yousef R, Whitman D. 1992. Predator exaptations and defensive adaptations in evolutionary balance: no defence is perfect. Evolutionary Ecology 6: 527–536.