Introduction

Florida is home to a large number of invasive as well as native species of thrips. Hot temperatures and high humidity are important factors supporting huge populations of thrips in Florida. In the genus Frankliniella, the common blossom thrips, F. schultzei Trybom, is a relatively new vegetable pest in south Florida. It is a key pest in tomato and cucumber fields in South America.

Synonymy

In Australia, F. schultzei was earlier known as F. lycopersici Steele, while in South America it was described as F. paucispinosa Moulton (Sakimura 1969).

Other synonymies of F. schultzei include:

-

F. interocellaris Karny

-

F. sulphurea Schmutz

-

F. delicatula Bagnall

-

F. dampfi Priesner (1923)

-

F. dampfi interocellularis Karny (1925)

-

F. lycopersici Andrewartha (1937)

-

Parafrankliniella nigripes Firault (1928)

-

F. paucispionosa Moulton (1933)

-

F. sulphurea Schmutz (1913)

-

Physopus schultzei Trybom (1910)

-

Euthrips gossypii Shiraki (1912)

-

F. delicatual Bagnall (1919)

-

F. trybomi Karny (1920)

-

F. persetosa Karny (1922)

-

F. tabacicola Karny (1925)

-

F. africana Bagnall (1926)

-

F. agnlicana Bagnall (1926)

-

F. aeschyli Girault (1927)

-

F. kellyana Kelly & Mayne (1934)

-

F. dampfi nana Priesner (1936)

-

F. favoniana Priesner (1938)

-

F. pembertoni Moulton (1940)

-

F. clitoriae Moulton (1940)

-

F. schultzei nigra Moulton (1948)

-

F. ipomoeae Moulton (1948)

-

F. insularis (Franklin) Morison (1930)

Distribution

The common blossom thrips has a very wide distribution and is mainly found in tropical and subtropical areas throughout the world (Vierbergen and Mantel 1991).

Reported worldwide distribution is as follows:

-

Africa: Angola, Botswana, Cape Verde, Chad, Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Libya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Morocco, Namibia, Niger, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Uganda, Zimbabwe

-

Asia: Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Java, Malaysia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka

-

Australia and South Pacific: Australia (New South Wales, Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia, Victoria, Western Australia), French Polynesia, Papua New Guinea

-

Central America and Caribbean: Barbados, British Virgin Islands, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Puerto Rico

-

Europe: Belgium, mainland Spain, Netherlands, Spain, United Kingdom

-

North America: United States (central and southern Florida, Colorado, Hawaii

-

South America: Argentina (Rio de Janeiro), Brazil (Minas Gerais, Parana, Rio Grande do Norte, Santa Catarina, Sao Paulo), Colombia, Chile, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela

Description

Frankliniella schultzei manifest two different color morphs, a dark and a pale form (Sakimura 1969). The two forms are anatomically similar to each other (Mound 1968). Sakimura (1969) reported the varied distribution of the two color morphs across the globe:

The dark form is mainly distributed:

-

south of the Sudan to the Cape in Africa,

-

from the Philippines to the south shore of Australia in western Pacific region,

-

from the Caribbean to the south of Argentina in South America,

-

Florida and Colorado in North America,

-

The Netherlands in Europe, and

-

throughout India in Asia.

The light form exists in:

-

Egypt, Sudan, Uganda, and Kenya in Africa,

-

Hawaii in North America,

-

India, and

-

New Guinea in the western Pacific region.

Mixed colonies of both color forms are reported by Mound (1968) in Egypt, India, Kenya, Puerto Rico, Sudan, Uganda, and New Guinea.

Thrips are very small insects. Adult females are 1.1-1.5 mm long, whereas adult males are 1.0-1.6 mm in length. Thrips species usually are identified by body color, body setae, and a comb on the 8th abdominal segment. The following text and images describe identifying characteristics of F. schultzei.

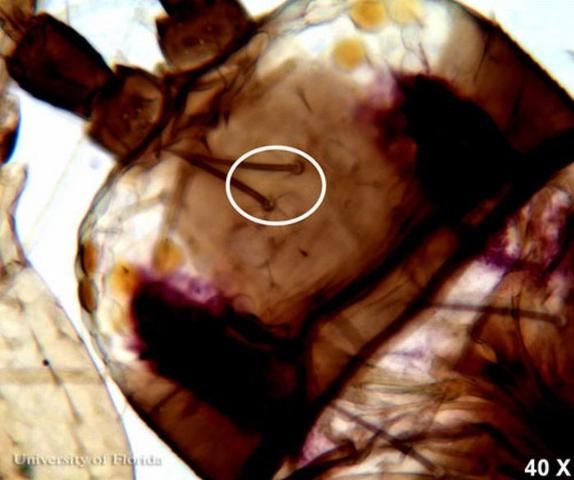

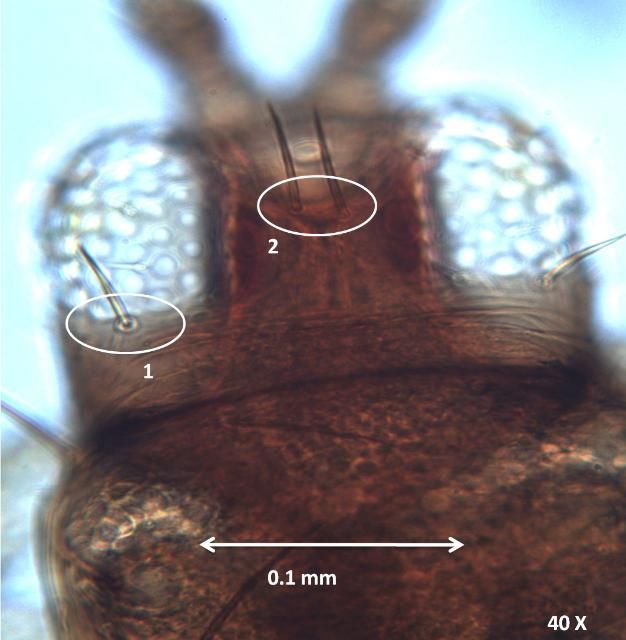

The interocellar setae arise along an imaginary line across the front edges of the two hind ocelli.

The postocular setae are slightly shorter than interocellar setae on the head of adult female F. schultzei.

Credit: Vivek Kumar, University of Florida

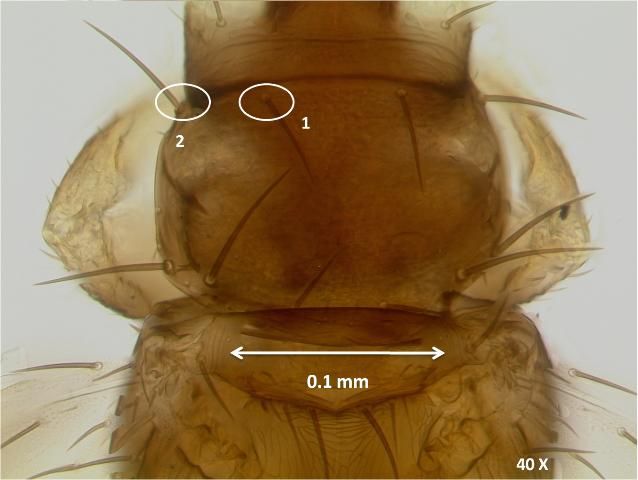

The anteromarginal setae are slightly shorter than anteroangular setae on the anterior of the prothorax.

Credit: Garima Kakkar, University of Florida

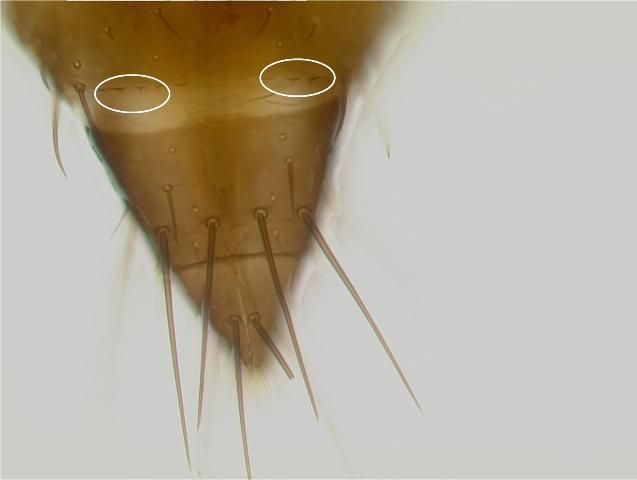

The abdominal comb is weakly developed on the 8th abdominal segment.

Credit: Garima Kakkar, University of Florida

THRIPS: A Knowledgebase of Vegetable Thrips, developed by Glades Crop Care and the University of Florida, includes a graphical identification key for a number of thrips species, including F. schultzei, and is available online at http://www.gladescropcare.com/resources/thrips-knowledgebase [19 October 2012] (Frantz and Fasulo 1997).

Life Cycle

There are two larval instars and two inactive and non-feeding stages in the life cycle. The latter two stages are known as prepupa and pupa. Females of F. schultzei insert their eggs in flower tissue. Silvia et al. (1998) in Brazil studied this thrips life cycle at 24.5°C and reported that a complete generation takes around 12.6 days. The embryonic stage lasts for four days and the 1st and 2nd larval instars, prepupa and pupa take an average of 2.5, 2.5, 1.2, and 2.1 days respectively. The adult female and male longevity is approximately 13 days.

Hosts

Frankliniella schultzei is a polyphagous pest feeding on various ornamental and vegetable hosts in different parts of the world (Milne et al. 1996). It has been recorded from 83 species of plants among 35 families (Palmer 1990). The major hosts of F. schultzei are cotton, groundnut, beans, and pigeon pea.

However, due to its polyphagous feeding behavior, F. schultzei also attacks tomato, sweet potato, coffee, sorghum, chillies, onion, and sunflower (Hill 1975).

Economic Importance

Crops suffering economic damage due to F. schultzei in different parts of the world include tomato, tobacco, cotton, grain legumes, groundnuts, and lettuce in India; ladys fingers, thistle, Japanese daisies, irises, spinach, tomato, carnation, pumpkin, carola (Tagates erecta), aubergine, and kidney beans in Cuba; Allium sp. (cepa) flowers in The Netherlands; and cotton, tomato, lettuce, pepper, cucumber, and tobacco in Brazil.

Frankliniella schultzei can cause both direct and indirect damages to crops. Both adults and nymphs feed on pollen and floral tissue, leading to flower abortion. Severe infestations can cause discoloration and stunted growth of the plant (Amin & Palmer 1985). However, indirect damage by F. schultzei is due to the virus transmission.

Tomato spotted wilt virus (Tospovirus) is a serious virus causing damage to a wide range of plant species (Prins and Goldbach 1998). The tospoviruses can only be transmitted by thrips, and in Florida, four species in the genus Frankliniella are responsible for the transmission of tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV). These are F. bispinosa, F. fusca (Hinds), F. occidentalis, and F. schultzei (Mound 2004).

The dark form of F. schultzei is known to vector at least four tospoviruses: TSWV (Sakimura 1969, Wijkamp et al. 1995) causing damage to tomato crops in Brazil (Monteiro et al. 2001) and in Paraguay (Ishijima 2002); tomato chlorotic spot virus (TCSV); groundnut ringspot virus (GRSV) (Wijkamp et al. 1995) affecting several crops in Africa (Nakahara 1997); and chrysanthemum stem necrosis virus (Nagata and de Avila 2000). However, the pale form of F. schultzei is reported to be a weak vector of TSWV and TCSV and a non-vector of GRSV (Sakimura 1969, Cho et al. 1988). Recently in Florida, a new incidence of TCSV on tomatoes has been recorded and its spread has been associated with F. schultzei (Londoño et al. 2012).

Management

Sampling. Frankliniella schultzei is an anthophilous thrips species and is frequently found feeding on the flowers of its host plant (Kakkar et al. 2012). Like other thrips, F. schultzei can also be sampled using colored sticky traps. A study done in Australia reported sexual discrepancies among F. schultzei in color preference. In that study, male thrips were most attracted to yellow sticky traps while female thrips were more attracted to pink sticky traps (Yaku et al. 2007).

Biological control. Two generalist predatory mites, Amblyseius cucumeris Oudemans and A. swirskii Athias-Henriot, known for their potential in controlling soft-bodied insect pests including thrips were tested against F. schuitzei. The two mites fed voraciously in Petri dishes under laboratory and were found to have potential in suppressing F. schultzei. When tested in shadehouse and field conditions, the two mites spp. failed to control F. schultzei in the presence of other thrips inhabiting cucumber leaves. It is assumed that the two mites could be effective in controlling F. schultzei in single pest situations (Kakkar et al. 2016).

Selected References

Amin PW, Palmer JM. 1985. Identification of groundnut Thysanoptera. Tropical Pest Management 31: 268-291.

Cho JJ, Mau RFL, Hamasaki RT, Gonsalves D. 1988. Detection of tomato spotted wilt virus in individual thrips by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Phytophathology 78: 1348-1352.

Frantz G, Fasulo TR. (1997). THRIPS: A Knowledgebase of Vegetable Thrips. Glades Crop Care. http://www.gladescropcare.com/resources/thrips-knowledgebase (4 September 2012).

Hill DS. 1975. Agricultural Insect Pest of the Tropics and Their Control, Cambridge University Press, London.

Ishijima, T. (ed.). 2002. Manual de técnicas de cultivo de hortalizas de fruta (tomate, melón, frutilla. National Institute of Agriculture, Caacupé, Paraguay. 240 pp.

Kakkar G, Seal DR, Kumar V. 2012. Assessing abundance and distribution of an invasive thrips Frankliniella schultzei (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in South Florida. Bulletin of Entomological Research.102: 249-259.

Kakkar G, Kumar V, Seal DR, Liburd OE, Stansly PA. 2016. Predation by Neoseiulus cucumeris and Amblyseius swirskii on Thrips palmi and Frankliniella schultzei on cucumber. Biological Control. 92: 85-91.

Londoño A, Capobianco H, Zhang S, Polston JE. 2012. First record of Tomato Chlorotic Spot Virus in the USA. Tropical Plant Pathology. 37 (5)-333-338.

Milne JR, Jhumlekhasing M, Walter GH. 1996. Understanding host plant relationships of polyphagous flower thrips, a case study of Frankliniella schultzei (Trybom). In Goodwin S, Gillespie P. (eds), Proceedings of the 1995 Australia and New Zealand Thrips Workshop: Methods, Biology, Ecology and Management, NSW Agriculture, Gosford. 8-14.

Monteiro RC, Mound LA and Zucchi RA. 2001. Espécies de Frankliniella (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) de importância agrícola no Brasil. Neotropical Entomology 1: 65-71.

Mound LA. 1968. A review of R.S. Bagnall's Thysanoptera collections. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Entomology. Supplement. 11: 1-181.

Mound LA. 2004. Australian Thysanoptera - biological diversity and a diversity of studies. Australian Journal of Entomology 43: 248-257.

Nagata T, De Avila AC. 2000. Transmission of chrysanthemum stem necrosis virus, a recently discovered tospovirus, by thrips species. Journal of Phytopathology 148: 123-125.

Nakahara S. 1997. Annotated list of the Frankliniella species of the world (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Contributions on Entomology, International 2: 355-389.

Palmer JM. 1990. Identification of the common thrips of tropical Africa (Thysanoptera: Insecta). Tropical Pest Management 36: 27-49.

Prins M, Goldbach R. 1998. The emerging problem of tospovirus infection and nonconventional methods of control. Trends in Microbiology 6: 31-35.

Sakimura K. 1969. A comment on the color forms of Frankliniella schultzei (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in relation to transmission of the tomato-spotted wilt virus. Pacafic Insects 11: 761-762.

Vierbergen G, Mantel WP. 1991. Contribution to the knowledge of Frankliniella schultzei (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Entomologische Berichten (Amsterdam) 51: 7-12.

Wijkamp I, Almarza N, Goldback R, Peters D. 1995. Distinct levels of specificity in thrips transmission of tospoviruses. Phytopathology 85: 1069-1074.

Yaku A, Walter GH, Najar-Rodriguez AJ. 2007. Thrips see red - flower colour and the host relationships of a polyphagous anthophilic thrips. Ecological Entomology 32: 527-535.