The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The order Mecoptera, often called the scorpionflies, is a relatively small order of insects that contains nine families and is distributed worldwide (Somma et al. 2014). Mecopterans, along with the orders that include the fleas (Siphonaptera), true flies (Diptera), caddisflies (Tricophtera) and moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera), comprise the group Panorpida (Grimaldi and Engel 2005). Panorpida is an important evolutionary grouping of insects within the holometabolous orders (those that have larval and pupal stages, rather than nymphs) fundamentally different from the beetles (Coleoptera) and the ants, bees, and wasps (Hymenoptera) (Grimaldi and Engel 2005). Within this group is the Antliophora, a monophyletic (arising from a single ancestor) grouping of Mecoptera, Diptera, and Siphonaptera, suggesting that the scorpionflies are most closely related to true flies and fleas (Grimaldi and Engel 2005, Somma et al. 2014).

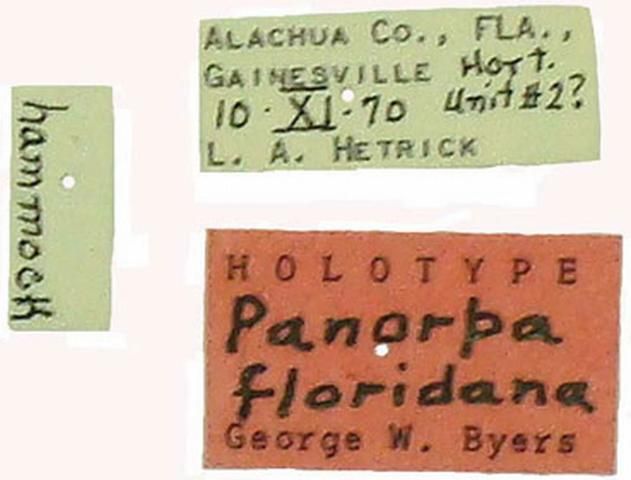

The Florida scorpionfly, Panorpa floridana Byers, is a little-known insect, endemic to northern peninsular Florida (Byers 1993; Somma and Dunford 2008). The first description of this species of scorpionfly (Panorpidae) in 1993 was limited to five specimens, the last one collected in 1982 (Byers 1993; Somma and Dunford 2008). This species has only been found in Alachua and Clay counties and was historically considered to be extremely rare (Somma et al. 2013). However, rather than being rare, this species is probably especially cryptic and difficult to locate in the wild.

Credit: Stephen Cresswell (photographic voucher FNAI Reference Code: N13CRE01FLUS, Reference ID: 189911; MorphoBank M152670)

Credit: Stephen Cresswell (photographic voucher FNAI Reference Code: N13CRE01FLUS, Reference ID: 189911; MorphoBank M152671)

Credit: James C. Dunford

Distribution

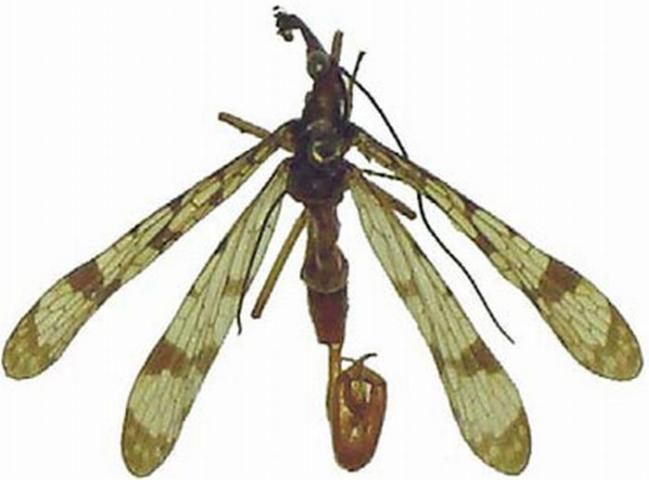

To date, Panorpa floridana is known only from specimens collected from Alachua and Clay counties in northern peninsular Florida. The two specimens from Alachua County are the holotype, a male collected in Gainesville near the San Felasco Hammock in 1970 (currently housed in the Florida State Collection of Arthropods [FSCA]; Figures 3 and 4); and a paratype, a female collected from an unspecified locality in 1974 (Byers 1993; Somma and Dunford 2008). The three original specimens from Clay County include the allotype, a female collected in Gold Head Branch State Park in 1982; a paratype, another female collected in Gold Head Branch State Park in 1982; and a paratype, a male collected in Orange Park in 1936 (Byers 1993). The lattermost Clay County specimen is housed in FSCA (Somma and Dunford 2008). A sixth photographic voucher was discovered in November 2010 in Mike Roess Gold Head Branch State Park in Clay County, Florida and was the subject of the first photographs of a living Florida scorpionfly (Somma et al. 2013). The scorpionfly, a male, was photographed resting on a holly shrub (Ilex sp.), near a source of moving water in the deep ravine (Somma et al. 2013) (Figures 1, 2, 5, and 6). Lastly, three more specimens collected from 1990–1996 and donated to FSCA in 2015, are all from this same ravine and include a seasonal record; a female collected on 24 October 1990.

Credit: James C. Dunford

Identification

Mecoptera are a small, ancestral order of holometabolous insects consisting of more than 605 known, extant species arranged in 34 genera and nine families worldwide (Penny 1975, 2008; Grimaldi and Engel 2005; Dunford et al. 2013; Dunford and Somma 2008a, b). The family Panorpidae is represented by one genus, Panorpa Linnaeus, and greater than 58 species in North America (Byers 2005; Dunford and Somma 2008a, b; Penny 2008). There are at least seven known species of Panorpa indigenous to the state of Florida (Somma and Dunford 2008). Panorpids can be distinguished from other mecopterans indigenous to Florida, bittacids (hangingflies) and meropeids (earwigflies), by the presence of two pretarsal claws (only one in bittacids) and ocelli (lacking in meropeids) (Byers 1993, 2005; Dunford and Somma 2008a, b). Moreover, the enlarged genital bulb of males is held curled above the dorsum of the abdomen like a scorpion's stinger, a feature lacking in hangingflies and earwigflies (Byers 2005; Somma and Dunford 2008).

Panorpa floridana can be distinguished from other Floridian panorpids by the following combination of characters (Byers 1993): Body length 18.3–18.5 mm; color is an overall dark yellowish brown. Color of head dark yellowish brown to reddish brown, with a dark brown to black ring around each ocellus. Wings lightly tinged with yellowish brown; pterostigmal band diagonal, unbranched; humeral area of wing clear, without spots; basal band strongly constricted at vein M. Hypovalves of sternum 9 of male less than one-third length of elongate genital bulb, excluding dististyles, and borne on prolongation of sternum on ventral surface of bulb; tergum 9 narrowed toward subacute apex, lacking posterior lobes. Genital plate of female lacking posterior lobes on apical plate, axial portion thick, its apodemes only slightly divergent.

Credit: Stephen Cresswell (photographic voucher FNAI Reference Code: N13CRE01FLUS, Reference ID: 189911; MorphoBank M152670)

Species in Florida with somewhat superficially similar genitalia include the black scorpionfly, Panorpa lugubris Swederus, and the red scorpionfly, Panorpa rufa Gray. However, Panorpa lugubris has overall black wings and a mostly black, or red and black body; while Panorpa rufa has a dark band along the anterior edge of the forewing from basal band to the wing base and the pterostigmal band is usually branched, with its outer or distal branch often joining the apical band near the wing margin (Byers 1993).

Natural History and Habitat

Habitat information on Panorpa floridana is based solely upon the meager information printed on the labels of the two Alachua County specimens, the 2010 rediscovery of this species, and the three recently acquired specimens, the latter four all from Clay County, Florida. The holotype was collected at a horticultural unit near a primarily mesic, mixed woods hammock known as the San Felasco Hammock (Byers 1993; Somma and Dunford 2008). This site, near the intersection of Millhopper Road and NW 71st Street, still exists and is occupied partially by units of the University of Florida Agricultural Experiment Stations, and the U.S. Geological Survey. The other Alachua County specimen was found "on saw palmetto" (Byers 1993). The two individuals collected in Mike Roess Gold Head Branch State Park, Clay County, likely were collected in the deep, mossy, mesic ravine formed by Gold Head Branch, as the surrounding sandy, upland habit appears too xeric. This was verified by the sixth individual, also collected along Gold Head Branch, which was found on a low-growing holly shrub, 2–3 meters from the branch (Somma et al. 2013). The three specimens were donated to FSCA in 2015. Most panorpids tend to prefer mesic habitat with low, dense, herbaceous vegetation (Webb et al.1975; Marshall 2006; Dunford et al. 2013; Dunford and Somma 2008a, 2008b). Five of the nine known specimens were collected in November, the single Orange Park and two recent Mike Roess Gold Head Branch State Park, Clay County individuals in December, and one other from the lattermost locality in October (Byers 1993; Somma and Dunford 2008; Somma et al. 2013; Somma pers. obs. 2015).

Credit: Stephen Cresswell (photographic voucher FNAI Reference Code: N13CRE01FLUS, Reference ID: 189911; MorphoBank M152668)

Prior to 2010, no living individuals of Panorpa floridana ever had been observed; thus, little is known of their habits and life history. Other species of Panorpa typically eat dead and moribund soft-bodied insects, supplemented with vertebrate and snail carrion, living slugs, bird droppings, pollen, nectar, and fruit juices (Byers 1963; Thornhill 1975; Webb et al. 1975; Byers and Thornhill 1983; Marshall 2006; Dunford and Somma 2008a, b). Many panorpid species are kleptoparasites of spider webs, feeding on the dead and trapped insects and occasionally the resident spiders themselves (Thornhill 1975; Bockwinkel and Sauer 1993).

The reproductive habits of Panorpa floridana also are unknown; however, other species of Panorpa are famous for ethological and sociobiological studies on their complex courtship behaviors which include various combinations of the use of pheromones, wing vibrations, stridulation, nuptial gifts of dead insects and salivary masses, and forced copulation (Rupprecht 1974; Thornhill 1980; Byers and Thornhill 1983; Thornhill and Alcock 1983). The eggs of Panorpa floridana are undiscovered but are likely deposited in loose cavities in the soil as in other species of Panorpa (Byers 1963; Byers and Thornhill 1983; Dunford and Somma 2008a, 2008b). Additionally, both the larval and pupal stages of Panorpa floridana are unknown; however, in other scorpionfly species, the larvae are soil- and litter-dwelling, eruciform, caterpillar-like scavenger-predators, and the pupae are exarate (with body appendages not appressed to the body) and decticous (able to use their mandibles in the pupal state) (Byers 1987, 1993; Dunford and Somma 2008a, 2008b).

North American panorpids have no known agricultural importance. The enlarged genital bulbs of the males (and the insect's common name) may give the false impression of a venomous stinger. However, these structures are harmless to humans and instead are used for copulation, competitive grappling with other scorpionflies, and fending off spiders (Thornhill 1975; Byers and Thornhill 1983; Bockwinkel and Sauer 1993).

Panorpa floridana is Florida's only described endemic mecopteran and is seemingly rare (Somma and Dunford 2008). Specimens or reports of sightings should be turned in to the Florida State Collection of Arthropods. Until more discoveries of Panorpa floridana have been made, the biological and economic role of this scorpionfly in northern peninsular Florida will remain unknown.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Wm. Charles Whitehill (Assistant Curator, FSCA) for providing us with important literature. We thank Gary J. Steck (Curator of Diptera and Minor Orders, FSCA) for reviewing the manuscript for this circular. Lastly, we are pleased to thank James R. Wiley (Research Associate, FSCA) for obtaining crucial literature for this circular and providing a critical review.

Selected References

Bockwinkel G, Sauer K-P. 1993. Panorpa scorpionflies foraging in spider webs - Kleptoparasitism at low risk. Bulletin of the British Arachnological Society 9: 110-112.

Byers GW. 1963. The life history of Panorpa nuptialis (Mecoptera: Panorpidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 56: 142-149.

Byers GW. 1987. Order Mecoptera. In Stehr FW. Immature insects. Volume 1. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Dubuque. pp. 246-252.

Byers GW. 1993. Autumnal Mecoptera of southeastern United States. University of Kansas Science Bulletin 55: 57-96.

Byers GW. 2005 (2004). Order Mecoptera. Scorpionflies and hangingflies. In Triplehorn CA, Johnson NF. Borror and DeLong's introduction to the study of insects. Seventh edition. Thomson Brooks/Cole. Belmont, CA. pp. 662-668.

Byers GW, Thornhill R. 1983. Biology of the Mecoptera. Annual Review of Entomology 28: 203-228.

Dunford JC, Somma LA. 2008a. Scorpionflies (Mecoptera). In Capinera JL. Encyclopedia of entomology. Second edition. Volume 4. S-Z. Springer. Dordrecht. pp. 3304-3310, plate 97.

Dunford JC, Somma LA. 2008b. Scorpionflies (Mecoptera). In Capinera JL. Encyclopedia of entomology EBook. Springer Science + Business Media B. V.; Dordrecht.

Dunford JC, Somma LA, Serrano D. 2013. FSCA Mecoptera resources: Mecoptera (scorpionflies, hangingflies, earwigflies, and allies) at the Florida State Collection of Arthropods. In Thomas MC. Museum of Entomology FSCA (Gainesville). Florida State Collection of Arthropods, Division of Plant Industry, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services; Gainesville. (10 June 2016).

Grimaldi DA, Engel MS. 2005. Evolution of the insects. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 772 pp.

Marshall SA. 2006. Insects: Their natural history and diversity: With a photographic guide to the insects of eastern North America. Firefly Books Ltd. Richmond Hill, Ontario. 718 pp.

Penny ND. 1975. Evolution of the extant Mecoptera. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 48: 331-350.

Penny ND. 2008. Mecoptera. In California Academy of Sciences Entomology. California Academy of Sciences; San Francisco. (28 June 2016)

Rupprecht R. 1974. Vibrationssignale bei der Paarung von Panorpa (Mecoptera/Insecta). Experientia 30: 340-341.

Somma, LA, Cresswell, S, Dunford, JC. 2013. Rediscovery of the Florida Scorpionfly, Panorpa floridana Byers (Mecoptera: Panorpidae). Insecta Mundi 0303:1-5 + MorphoBank Project No. p876.

Somma LA, Dunford JC. 2008. Preliminary checklist of the Mecoptera of Florida: earwigflies, hangingflies, and scorpionflies. Insecta Mundi 0042: 1-9.

Somma LA, Dunford JC, Serrano D. 2014. The Mecoptera collection of the Florida State Collection of Arthropods: Scorpionflies, hangingflies, earwingflies, and allies. Southeastern Biology 61: 110-113.

Thornhill R. 1975. Scorpionflies as kleptoparasites of web-building spiders. Nature (London) 258: 709-711.

Thornhill R. 1980. Competitive, charming males and choosy females: Was Darwin correct? Florida Entomologist 63: 5-30.

Thornhill R, Alcock J. 1983. The evolution of insect mating systems. Harvard University Press. Cambridge. 547 pp.

Webb DW, Penny ND, Marlin JC. 1975. The Mecoptera, or scorpionflies, of Illinois. Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin 31: 250 -316.