The Coconut Palm in Florida1

Scientific Name: Cocos nucifera Linn.

Family: Arecaceae

Origin

Comparatively little is known about the origin and early distribution of the coconut palm, probably because it was so widely spread throughout the tropical areas of the world so many years ago. However, the coconut palm is believed to be native to the Malay Archipelago or the South Pacific.

Distribution

The coconut is widespread throughout the tropics, typically being found along sandy shorelines. This tree has been spread largely by man, but also by natural means. The fruit can float for long distances and still germinate to form new trees after being washed ashore.

Commercial plantings are confined to the tropical lowlands, but the tree will also fruit in a few warmer subtropical areas. In Florida the coconut palm is successfully grown from Stuart on the east coast and Punta Gorda on the west coast, south to Key West.

Importance

The coconut is the most extensively grown and used nut in the world and the most important palm. It is an important commercial crop in many tropical countries, contributing significantly to their economies. Copra is the chief product of the coconut. Copra is the source of coconut oil, which is used for making soap, shampoo, cosmetics, cooking oils, and margarine. Much of the fruit is consumed locally for food.

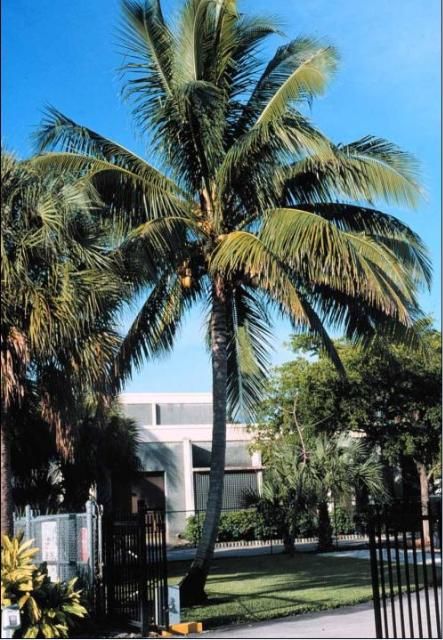

The coconut palm, more than any other plant, gives a tropical effect to the Florida landscape. While this palm is highly valued as an ornamental, it is also grown on a limited commercial basis in Florida for coco frio, a refreshing drink made from the water inside green coconuts.

Description

Tree. This large, single-trunked palm has a smooth, columnar trunk with a light grayish-brown color; the trunk is topped with a terminal crown of leaves. Tall varieties may attain a height of 80–100 feet (24–31 m), while dwarf varieties are shorter in stature. The trunk is slender and often swollen at the base. The trunk is typically curved or leaning, but is erect in some cultivars.

Leaves. The pinnate leaves are feather-shaped, up to 18 feet (5.5 m) long and 4 feet (1.2 m) wide. The leaf stalks are 3–5 feet (0.9–1.5 m) in length and spineless.

Flowers. Male and female flowers are borne on the same inflorescence. The inflorescences emerge from canoe-shaped sheaths among the leaves and may be 2–3 feet (0.6–0.9 m) long and have 10–50 branchlets. Male flowers are small, light yellow, and are found at the ends of the branchlets. Female flowers are larger than male flowers, light yellow in color, and are found towards the base of the branchlets. Coconut palms begin to flower at about 4–6 years of age.

Fruit. Roughly ovoid, up to 15 inches (38 cm) long and 12 inches (30 cm) wide, composed of a thick, fibrous husk surrounding a somewhat spherical nut with a hard, brittle, hairy shell. The nut is 6–8 inches (15–20 cm) in diameter and 10–12 inches (25–30 cm) long. Three sunken holes of softer tissue—called "eyes"—are at one end of the nut.

Inside the shell is a thin, white, fleshy layer, about one inch thick at maturity. This layer is known as the "meat" or copra. The interior of the nut is hollow, but partially filled with a watery liquid called "coconut milk". The meat is soft and jelly-like when immature, but it becomes firm at maturity. Coconut milk is abundant in unripe fruits, but the coconut milk is gradually absorbed as ripening proceeds. The fruits are green at first, turning brownish as they mature. Yellow-fruit varieties change from yellow to brown as they mature.

Production

The coconut palm starts fruiting 6–10 years after the seed germinates and reaches full production at 15–20 years of age. The tree continues to fruit until it is about 80 years old, with an annual production of 50–200 fruits per tree, depending on cultivar and climate. The fruits require about a year to develop and are generally produced regularly throughout the year.

Cultivars

Several cultivars of coconut palms are grown in Florida (Table 1). These cultivars differ in their petiole and fruit color, straightness (or crookedness) of the trunk, leaflet and leaf width, growth rates, presence or absence of a swollen trunk base or bole, adaptability to Florida's soil conditions, and resistance to lethal yellowing disease (LY).

The 'Jamaican Tall' (also called 'Atlantic Tall') is a rapid-growing coconut palm variety with a swollen trunk base and crooked trunk. This variety is well adapted to Florida. The 'Malayan Dwarf' cultivar has three color forms that differ in the color of the immature fruits and petioles (green, yellow, or gold). This cultivar is smaller and slower-growing than the 'Jamaican Tall'. Additionally, the 'Malayan Dwarf' has a narrow, straight, non-swollen trunk. The 'Panama Tall' (also called 'Pacific Tall') is a large, robust palm with a large-diameter trunk that is crooked and swollen. The 'Panama Tall' has a rapid growth rate and either green or bronze-colored fruits and petioles. The 'Maypan' is a hybrid between the 'Malayan Dwarf' and the 'Panama Tall' and resembles the 'Jamaican Tall' in appearance.

The 'Malayan Dwarf' cultivar and the hybrid 'Maypan' have been widely planted in Florida because of their reported resistance to LY, a fatal disease of coconut palms in Florida and in parts of the Caribbean region. (For more on this disease, see EDIS Publication PP222, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pp146.) Although these varieties were originally believed to be highly resistant to LY, long-term trials in Florida have revealed that 'Malayan Dwarf' and 'Maypan' are only slightly less susceptible to LY than the 'Jamaican Talls' these varieties were intended to replace.

One cultivar that has shown some potential for resistance to LY is the 'Fiji Dwarf' (Niu Leka), although more extensive testing is needed to substantiate the promising results of studies done in Florida during the 1980s and 1990s. The 'Fiji Dwarf' is slow growing and has very broad leaves and leaflets. This variety can have either bronze or green fruits and petioles and has a very thick, crooked trunk. The 'Fiji Dwarf' is well adapted to Florida soils. Unfortunately, unless 'Fiji Dwarf' trees are isolated (>100 ft or so) from other coconut palm cultivars, to prevent pollination with non-'Fiji Dwarf' trees the resulting seeds produce a good percentage of tall, off-type palms that are known to be susceptible to LY.

Propagation

Coconut Palm propagation is entirely from seed—the coconuts, which are ready for planting if they produce an audible "sloshing" sound when shaken. The nuts are placed on their sides and buried with sand or mulch to about one-half the thickness of the nut. They may be planted in closely spaced rows in well drained seedbeds, or the nuts may be planted directly into large pots. Germination is best under high temperatures (90°F–100°F). Upon germination, the shoot and root emerge through the side or one end of the nut. Young palms, about 6 months old, can be transplanted directly into the field or can be grown in pots in the nursery for a few more years.

Climate and Soils

The coconut palm is typically found along tropical, sandy shorelines since it can tolerate brackish soils and salt spray. However, salt is not required for the growth of healthy coconut palms, which can be successfully grown well inland. Coconut palms grow well in a wide range of soil types and in a wide pH range, from 5.0–8.0, provided the soils are well drained. Successful growth requires a minimum average temperature of 72°F and an annual rainfall of 30–50 inches or more. Coconut palms are not suitable for areas that regularly experience freezing temperatures. Coconut palms require full sunlight and are tolerant to wind and to temporary flooding.

Planting and Spacing

Coconut palms may be planted at any time of the year, but the warm, rainy summer months are best for planting these palms. They can be successfully transplanted at any period in their growth, provided they are properly handled. Preplanting soil preparation depends upon soil type and depth of the water table. In low-lying areas, beds several feet high and wide should be constructed to prevent waterlogging of the root zone during wet periods. In some areas a hardpan in the soil profile may need to be broken up and mixed with topsoil prior to planting. For commercial plantings in the rocky calcareous soils of Miami-Dade County, rock plowing to a depth of 6–8 inches (15–20 cm) and trenching about 16–24 inches (41–60 cm) wide and 18–24 inches (45–60 cm) deep is recommended. For landscape planting, holes 2–3 ft in diameter and 1–2 ft deep should be prepared. Before digging in landscapes, contact your local utilities to avoid disrupting water, cable and/or electrical lines.

Container-grown palms should be planted such that the bottom of the stem and top of the root system are about 1 inch below the surface of the soil. Field-grown palms should be planted at the same level at which they were previously grown. The new tree should be watered immediately after planting and frequently thereafter until the tree is well established. Three to four inches, but no more, of mulch applied to the soil surface around the tree will help retain soil moisture and restrict weed growth. Commercially, the trees are planted at spacings of 18–30 feet (5.5–9.1 m) apart. In home gardens, coconut palms should be planted where they will receive full sun and not be crowded. At least 1 inch of water should be supplied weekly by rainfall or by irrigation, especially during the first year following transplanting.

Environmental Stresses

Drought: Coconut palms are tolerant of dry soil conditions. However, for optimum fruit production and quality, regular irrigation is recommended during dry periods.

Flooding: Coconut palms are tolerant of waterlogged or flooded soil conditions for a few days. However, trees may decline and die when exposed to prolonged flooding or waterlogged soils.

Cold temperatures: Coconut palms will be injured and may be killed by temperatures below 32°F (0°C) and may show chilling injury symptoms of leaflet necrosis at temperatures as high as 40°F (5°C). Prolonged exposure to non-freezing temperatures in the low to mid 30s°F can result in permanent trunk damage and even death of the palm. More severe freezes can also result in death of the bud. Research has shown that the severity of cold injury is greatly reduced for these palms when they have been properly fertilized. (For additional information about cold damage on palms, see EDIS publication MG318, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg318.)

Wind: Coconut palms are quite tolerant of windy sites and generally survive hurricane-force winds. The most common damage from hurricane winds is loss of leaves and toppling over. If uprooted palms are righted promptly and adequately watered, survival of these palms is usually quite good.

Salt: Coconut palms are tolerant of saline water and soils, as well as salt spray.

Lightning: Lightning occasionally strikes tall coconut palms. Symptoms of lightning strikes include sudden collapse of the canopy and bleeding exit holes in the bottom four feet of the trunk.

Nutritional Problems and Fertilization

Coconut palms in the landscape are susceptible to several nutritional deficiencies. Nitrogen (N) deficiency appears as a uniform yellowing of the oldest leaves but typically affects the entire canopy. Growth rate will be sharply reduced. (For more on N deficiency in palms, see EDIS Publication ENH1016, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep268.)

Potassium (K) deficiency is probably the most widespread and important deficiency of coconut palms throughout the world. Early symptoms occur first on the oldest leaves as translucent yellow-orange or necrotic spotting. Necrosis of the leaflet margins, followed by leaflet tip necrosis will also become apparent. Symptoms increase in severity towards the tip of the leaf. In severe cases the trunk will begin to taper in diameter ("pencil-pointing"), and new leaves will emerge chlorotic, short, and frizzled in appearance. Death often follows if immediate treatment is not provided. The most effective treatment for K deficiency is sulfur-coated potassium sulfate, broadcasted under the canopy at a rate of 1.5 lbs/100 sq. ft. of canopy area four times per year. Addition of 1/3 as much magnesium (Mg) at the same time will prevent a Mg deficiency from following treatment for K deficiency. (For more on K deficiency in palms, see EDIS Publication ENH1017, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep269.)

Magnesium deficiency appears as broad, yellow bands along the outer edges of the oldest leaves in the canopy. The center of the affected leaves will remain distinctly green with this deficiency. It is usually treated with magnesium sulfate, preferably in controlled release form to reduce leaching losses. (For more on magnesium deficiency in palms, see EDIS Publication ENH1014, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep266.)

Manganese (Mn) deficiency sometimes occurs on coconut palms, particularly in the spring months following a cold winter. Symptoms occur on the newest leaves, which emerge greatly reduced in size. These leaves will typically exhibit a singed appearance along the edges. Manganese deficiency can also be caused by fertilization or by soil amendment with composted sewage sludges. Although Mn deficiency caused by cool soil temperatures is usually a temporary problem, Mn deficiency caused by composted sewage sludges can be fatal if manganese sulfate is not promptly and regularly applied. For this reason, composted sewage sludges should not be used on any ornamental plants that are susceptible to Mn deficiency. (For more on Mn deficiency in palms, see EDIS Publication ENH1015, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep267.)

Boron (B) deficiency occasionally occurs on coconut palms, particularly during rainy weather, which leaches B through sandy soils. Extended periods of dry weather, as well as high soil pH, can also contribute to B deficiency. Symptoms include premature fruit drop and tip dieback on new leaves. Sometimes a sequential pattern of triangles will appear within a single new leaf as the palm alternately experiences B deficiency and sufficiency during leaf development. Chronically boron-deficient palms often exhibit one or more incompletely opened spear leaves. Boron deficiency can be treated with sodium borates (Solubor or borax) or boric acid. (For more on B deficiency in palms, see EDIS Publication ENH1012, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep264.)

To prevent nutritional deficiencies from occurring or to correct mild deficiencies, regular maintenance fertilization with a "palm special" fertilizer is recommended. These fertilizers should have an analysis of approximately 8N-2P2O5-12K2O-4Mg. The fertilizers should also have all of their N, K, and Mg in a controlled-release form to prevent rapid leaching of these nutrients through the soil. Additionally, the fertilizers should contain about 1%–2% Fe and Mn, plus trace amounts of Zn, Cu, and B. (For more on fertilization of palms in Florida, see EDIS Publication ENH1009, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep261.)

The most effective way to apply these fertilizers is with a rotary spreader, covering the entire soil area beneath the canopy of the palm (usually about 450–500 sq. ft.) A rate of 1.5 lb of palm special fertilizer per 100 sq. ft. of canopy area every three months or 1 lb/100 sq. ft. every two months is ideal. In areas of low rainfall or in areas having soils with high cation exchange capacities, rates and application frequencies can be reduced.

Diseases

Lethal yellowing is the most important disease of coconut in Florida. Since LY was discovered in Key West more than 200 years ago, this disease has crept northward, killing hundreds of thousands of palm trees and endangering virtually all of the tall coconut palms in Florida. Lethal yellowing is caused by a tiny organism called a phytoplasma, which is visible only with the aid of an electron microscope. Early symptoms of LY are premature dropping of coconuts and blackening of flower stalks. The palm leaves then turn yellow, beginning with the lower leaves and progressing to the crown, which dies and eventually topples from the tree. The tree usually dies within six months after exhibiting the first symptoms of LY. (For more on this disease, see EDIS Publication PP222, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pp146.)

Leaves of Malayan Dwarf coconuts do not show the typical yellowing symptoms, but instead become wilted and turn brown before the bud eventually dies. Injection of an antibiotic (oxytetracycline) may result in remission of symptoms within four weeks, but additional applications at four-month intervals are required to keep the tree alive. Antibiotic injection is best when used on a preventive basis when LY is active in the area. Roguing and destruction of the infected palms and replacement of those palms with non-susceptible palm species is recommended.

Bud rot, caused by the fungus Phytophthora palmivora Butler, is found in all areas where the coconut palm is grown. Early symptoms—found on young, developing leaves—are brown, sunken spots, yellowing, and/or withering. The leaves turn a light grayish brown, becoming darker brown as they collapse at the base. The infection spreads inward to the bud and outward to surrounding leaves, which turn yellow and fall. Young nuts fail to develop, and they fall. However, nuts that are well formed before infection continue to mature. A disagreeable odor emanates from the decaying bud. The older leaves in the canopy of an infected tree typically remain healthy looking for up to six months following death of the bud.

Both juvenile and adult trees can be affected. Disease development most commonly occurs after periods of heavy rains and is prevalent in poorly drained sites. Once symptoms become visible, treatment is seldom successful. This disease can be prevented by periodic foliar sprays with fosetyl-Al (Aliette) or other products containing phosphorous acid or phosphites. Palms showing advanced symptoms of bud rot should be removed and destroyed since these plants may serve as a source of inoculum. (For more on bud rots, see EDIS Publication PP220, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pp144.)

Thielaviopsis trunk rot is a lethal fungal disease that causes one-sided trunk rot and ultimately, collapse of the trunk or crown. This disease requires a wound in soft trunk tissue; thus, the disease is most commonly seen in recently transplanted coconut palms. There is no treatment for this disease, and it is best prevented by avoiding trunk wounds, particularly in the upper half of the trunk. (For more on this disease, see EDIS Publication PP219, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pp143.)

Pests

A number of pests—including several kinds of scale, palm aphid, spider mites, mealybugs, palm weevils, and caterpillars—are occasionally found, but usually do not require control measures. Coconut scale occasionally may cause extensive damage, and heavy infestations should be controlled by appropriate measures. Nuts showing constriction and/or a rough, corky surface are infested with coconut mites. Palm leaf skeletonizers mine the leaflets, leaving behind dead, translucent patches of leaf tissue and the insect's brown frass tubes on the undersides of the leaves. Current control recommendations may be obtained from your local UF/IFAS Extension agent.

Harvesting

Harvesting of coconuts occurs throughout the year. The time from fruit set to full maturity is about 12 months. The fruit should be harvested fully ripe for copra and dehydrated coconut. Drinking nuts should be picked earlier, at about seven months. The nuts may be harvested by skilled climbers or may be cut from the ground, using a knife attached to a long pole. Use of climbing spikes is not recommended since the wounds caused by the spikes are permanent and may provide entry sites for diseases, such as Thielaviopsis trunk rot.

Uses

There are literally hundreds of uses for coconuts and their products. The meat of immature coconuts can be eaten with a spoon or be scooped out and made into ice cream. Coconut milk, abundant in unripe nuts, is a refreshing and nutritious drink. The meat in mature coconuts is firm and can be eaten fresh or may be used for making shredded coconut. The most important economic product of the coconut is obtained by drying the meat into copra, which is pressed to produce coconut oil, primarily used in making soap and cosmetics. Coconut oil is also used for cooking and making margarine. The husk fiber is combed out and sold as coir, a material for making rope and coconut matting. Coir dust is an excellent substitute for peat moss in potting soils. The coconut palm trunks may be used for building timbers and the leaves used for house thatching. The coconut palm has little commercial importance in Florida but is highly valued as an ornamental. The coconut palm gives a tropical effect to the Florida landscape and provides fruit for home use.