Introduction and Purpose

Most turf and ornamental fertilizers available to homeowners contain nitrogen (N) because it is an important plant nutrient that is often deficient in Florida soils. If these fertilizers are misused, N can be transported from the landscape with rain or irrigation water, possibly contaminating nearby water bodies. Understanding how N reacts in the landscape can help us maximize plant growth and minimize harmful loss of N in the environment. This document helps homeowners understand how N interacts in the environment through the N cycle, making maintenance of home landscapes or gardens easier and more sustainable.

The Nitrogen Cycle

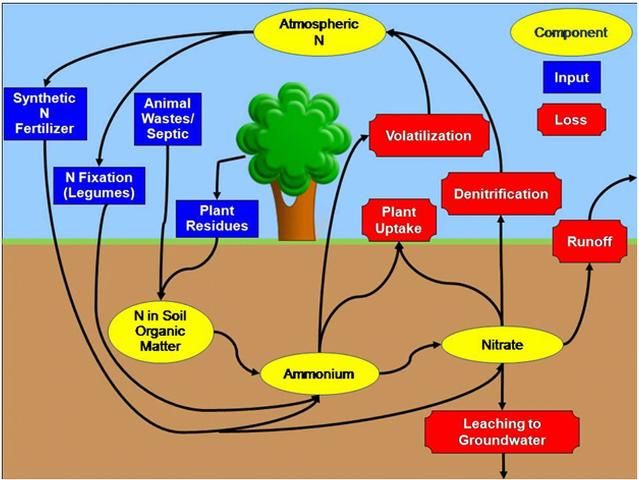

Let's begin our discussion of the N cycle in a home landscape by considering the grass clippings left on the lawn surface after mowing. These clippings provide a source of organic matter to the soil. Organic matter contains forms of N that are not available to growing plants. However, soil microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, change the unavailable forms of N into inorganic N forms that are plant-available. Inorganic N is then taken up by the roots of the growing grass. When the grass is mowed again, this cycle repeats (Figure 1). This description is an oversimplified example of the N cycle. We will now go into more detail.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Sources of Nitrogen

Plant residues are not the only source of N in the soil (Figure 1). The fertilizer industry also manufactures lawn and ornamental fertilizers that are used by homeowners. Most of these materials contain plant-available N in the form of ammonium (NH4+) or nitrate (NO3-). Another form of N that can be synthesized by fertilizer manufacturers and that you may find in lawn and landscape fertilizers is urea. Once urea is applied to the soil, it is quickly converted to ammonium by urease, a natural soil enzyme. Synthetic N fertilizers containing ammonium, nitrate, or noncoated forms of urea are considered to be "quick-release" fertilizers, which means that the N dissolves in water almost immediately after application to become plant-available. Because dissolved N can be an immediate environmental hazard (more information below), quick-release fertilizers should be applied to the landscapes at low rates (per single application). UF/IFAS recommendations call for applying ½ pound of a water-soluble N source per 1,000 square feet of turfgrass. No more than 0.7 lb of soluble (quick-release) N per 1,000 square feet should be applied at any given time (see EDIS publication ENH1089, Urban Turf Fertilizer Rule for Home Lawn Fertilization, at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/ep353). Some companies also produce slow-release or controlled-release fertilizers that are designed to delay the release of plant-available N. This allows for more N to be added to the landscape during a single application than when using quick-release fertilizer. It is important to understand that quick-, slow-, and controlled-release N fertilizers can be equally harmful to the environment if they are not applied properly. For more information about available lawn and landscape fertilizers, see EDIS publication SL266/MG448, Soils & Fertilizers for Master Gardeners: The Florida Gardener's Guide to Landscape Fertilizers (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/mg448).

Organic soil amendments like compost, peat, or manure contain forms of N that are not available for plants (i.e., chlorophyll, proteins, etc.) and small amounts of plant-available ammonium or nitrate. These materials are often derived from plant residues or animal wastes. Like the grass clippings from the earlier example, the forms of N in these materials that are not plant-available must be converted to ammonium by soil microbes. Remember, ammonium is the same form of N available in many synthetic fertilizers.

Another source of N to the soil is the atmosphere (Figure 1). The earth's atmosphere contains 78% N as N2, a nonreactive gas. While most plants and animals cannot use N2, there are a few microbes that can convert this gas into a plant-available form of N. These microbes can live freely in the soil or can colonize the roots of special plants called legumes. Soybeans, alfalfa, and peas are all legumes. While most legumes are not grown in the home landscape, perennial peanut is a legume that can be used as a ground cover in place of turf. Lightning can also convert N2 gas into plant-available forms of N. In addition, combustion of fossil fuel adds N to the atmosphere. When it rains, atmospheric N can be brought back to earth through atmospheric deposition. The amount of N added to the soil from these sources is very small compared with the amount added in organic matter and landscape fertilizers, but the atmosphere can be a major source of N for aquatic ecosystems.

A home septic system is also a source of N. Most of the N contained in domestic wastewater that enters a septic system will pass through the tank and be delivered to the septic drain field in a plant-available form.

How Does Nitrogen Behave in the Soil?

Once in the soil, all forms of N can undergo a variety of chemical changes. We already discussed how soil microbes can transform N in plant residues or organic soil amendments into plant-available N. This process is called mineralization, and the end product is ammonium. Once in the ammonium form, N can be taken up by plant roots. If ammonium is left on the soil surface, it can be lost to the atmosphere as ammonia gas via a process called volatilization. Ammonium can also be converted to nitrate by soil microbes through a process called nitrification.

Like ammonium, soil nitrate can be taken up by plants through the roots. If a soil remains waterlogged for a long time and loses its oxygen, nitrate can be converted to N2 gas by microbes and lost to the atmosphere through a process called denitrification. For more information on N transformations in urban environments, see EDIS publication SL468, Sources and Transformations of Nitrogen in Urban Landscapes (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/SS681).

Nitrogen and Water Quality

Nitrogen can be transported from the soil to surface or groundwater as the landscape drains following heavy rain or excessive irrigation. When the rainfall or irrigation rate exceeds the soil infiltration capacity, the result is runoff. Runoff can transport soil N, as well as recently applied landscape fertilizers and grass clippings, into lakes, ponds, streams, rivers and bays. In addition, soil N and N fertilizers can be carried downward, or leached, through the soil profile. Nitrate moves more quickly through the soil profile than ammonium or organic forms of N, but any form of N is capable of leaching into the soil. Once N is leached, it may eventually reach groundwater used for drinking or be discharged by our springs.

Once transported, N can become a water pollutant. For example, nitrate lost in leachate or runoff may contribute to eutrophication of Florida's surface water bodies. Eutrophication is the enrichment of water with nutrients that results in excessive aquatic plant (mostly algae) growth. Over time, oxygen depletion in eutrophic waters can lead to fish kills and their accompanying foul smell. Often, eutrophic water bodies can no longer be used for fishing, swimming, boating or other recreational activities. For more information on eutrophication and the role of N, see EDIS publication SGEF190, Rethinking the Role of Nitrogen and Phosphorus in the Eutrophication of Aquatic Ecosystems (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/sg118).

Can I Test My Soil for Nitrogen?

Unlike other plant nutrients, most laboratories do not test soil for N because the N cycle is very dynamic. This means that the forms of N in the environment are constantly changing (Figure 1). However, soil test results from a reputable laboratory will include information about N application rates for turf and ornamentals. These recommended rates are based on scientific research on plant response to N fertilizer rather than on the amount of N measured in your soil sample. Even though soils are not tested for N, soil tests are vital because they provide important information about soil pH and the levels of other important plant nutrients (i.e., phosphorus, potassium and magnesium) in the soil. Results from a soil test will help you properly manage nutrients in your home landscape.

How Can You Help Protect Water Quality?

As a homeowner in Florida, you can help protect water quality by following best management practices (BMPs) when using synthetic or organic fertilizers. First and most importantly, fertilize only when your plants need nutrients (i.e., times of active growth) and follow University of Florida recommendations for rates and timings. For information on fertilization requirements for Florida lawns, see EDIS publication SL21, General Recommendations for Fertilization of Turfgrasses on Florida Soils (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/LH014). When you do choose to fertilize your landscape, make sure to read the fertilizer label carefully. The label provides important information about how much N is in the fertilizer and what form it is in. Also, look for a fertilizer with some of the N in slow-release form. These products will provide a longer fertilizer response for your lawn and landscape and have less potential to leach if there is heavy rainfall or if fertilizer is overapplied. This information is also available on the fertilizer label. For more information about fertilizer labels and how to read them, see EDIS publication SL-3, The Florida Fertilizer Label (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SS170). Finally, if you spill fertilizer on the sidewalk or driveway, sweep it up and put it back in the bag or dispose of it properly by applying it to the target plants. Any fertilizer left on hard surfaces will be washed into the storm drain and discharged directly into a pond or stream. Similarly, sweep grass clippings back onto the yard, because they contain organic N and also can be carried to the storm drain in runoff.