Description

The Florida scrub lizard is a small, gray or gray-brown lizard with spiny scales and sometimes a reddish cast (Figure 1). Adults are about 5 inches in total length. A prominent characteristic of scrub lizards is a thick brown stripe that runs down each side of the body from the neck to the base of the tail. Adult males have bright turquoise patches on the sides of the belly and a black throat with small turquoise patches at the base. Females generally lack the turquoise patches but sometimes have faded patches on their bellies. Adult males usually have unmarked backs, whereas adult females have 7-10 wavy brown lines. The slightly larger fence lizard (Sceloporus undulatus) overlaps geographically with the scrub lizard in northern Florida but is easily distinguished from this species by the lack of the dark lateral stripe.

Credit: Kevin Enge

Distribution and Habitat

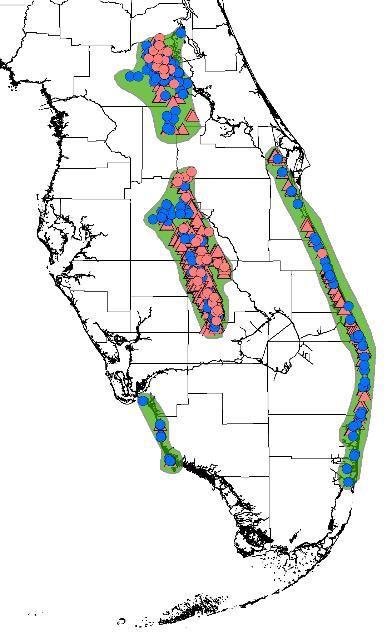

The range of the Florida scrub lizard is restricted entirely to Florida. These lizards presently occur in disjunct populations in central Florida and on the Atlantic Coast (Figure 2). Populations that once occurred along the Gulf Coast in Lee and Collier counties have been extirpated by urban development; the last record was in 1994. In the state's interior, scrub lizards are restricted to the Mount Dora, Winter Haven, Lake Wales, and Bombing Range ridges in Putnam, Marion, Lake, Orange, Osceola, Polk, and Highlands counties. Scrub lizards once occurred along the Atlantic Coast from Brevard to northern Miami-Dade County, but they now occur only as far south as Palm Beach County. Ocala National Forest contains the most habitat for the species. Scrub lizards are habitat specialists that live in dry uplands such as scrub, sandhill, and scrubby flatwoods. They require sunny areas with large amounts of bare sand adjacent to shrubs of trees that provide escape cover and shade. Scrub lizards are most common in habitats that have been kept open by fire or other disturbances, such as logging of sand pine, but also may persist for some time along the edges of more dense scrub. Scrub rosemary inhibits the growth of other vegetation and provides natural patches of bare sand suitable for scrub lizards. In unburned scrub and sandhill, manmade disturbances, such as sand roads and off-road vehicle trails, may allow populations to survive.

Credit: Enge 2019

Behavior and Diet

Scrub lizards forage on the ground and may perch on the base of tree trunks and on logs or other debris to detect their prey. They are active during warm days throughout the year. Activity is lower on cool days or during very hot hours in the summer. Startled lizards dash away and typically seek cover under shrub clumps in scrub habitat and up trees if shrubs are scarce, such as in sandhill habitat. Their diet consists of insects, spiders, and other small arthropods and even lizards. This species has very limited dispersal capabilities. Scrub lizards generally do not move through dense vegetation and are unlikely to disperse between scrub patches unless the patches are no more than a few hundred meters apart and connected by open areas.

Reproduction

Courtship and mating of scrub lizards occur from February through June. Females deposit 2-8 (usually 4-5) eggs in the sand beginning in March. A single female may lay eggs 3-5 times annually. Eggs deposited in April take about 75 days to hatch, but hatching time probably gets shorter as summer progresses and ground temperatures increase. Hatchlings appear from June until early November. Young lizards reach sexual maturity in 10-11 months, and some individuals may live up to 27 months in the wild.

Legal Status, Conservation Issues and Management

The scrub lizard is not listed as a threatened or endangered species at the state or federal level, but it was petitioned for federal listing in 2012. The primary conservation concern for scrub lizards is loss of habitat. Large areas of scrub have been converted to urban development and agriculture. Loss of habitat has caused a decline in scrub lizard populations and increased isolation of remaining populations. Small, fragmented populations are more vulnerable to extinction. Scrub patches 5-15 acres in size typically can support long-term populations, but as small patches of habitat become more isolated by housing projects and other development, lizards are not able to move between habitat patches to repopulate areas. Long-term survival of the Florida scrub lizard is dependent upon preservation of sufficient scrub habitat through growth management.

Suppression of fires, which are a natural component of the scrub ecosystem, also has resulted in habitat loss for scrub lizards. Scrub management should incorporate prescribed burns, or other practices, to reduce shrubs and ground cover and maintain open, sandy habitat for lizards. Mechanical treatment of scrub vegetation that results in a mulch layer inhibits mobility and foraging of scrub lizards. Habitat management for scrub lizards needs to be designed with consideration of the limited movement capabilities of this species, which is only a few hundred meters through unsuitable habitat. If scrub patches become so overgrown with dense vegetation that lizards disappear from the patch, lizards may not be able to recolonize unless restored areas are adjacent to habitats that can supply lizards. It may be possible to link patches that are farther apart with open corridors for scrub lizards, but more scientific research is needed to develop effective designs for corridors.

Because scrub lizards are restricted to dry, upland habitats that naturally occur in patches, populations in different parts of the state have been isolated from genetic exchange for thousands of years. Over evolutionary time, this isolation has resulted in high genetic diversity in scrub lizards and large genetic differences between populations. Conservation strategies for wildlife frequently involve translocation of animals between populations by managers. Careful consideration should be given to any plans for translocation of scrub lizards between populations because such movements may result in loss of the unique genetic diversity of different scrub lizard populations. Since 1986, the range of the species along the Atlantic Coast has contracted 48 miles northward, and its southern extent is now northern Palm Beach County. In 2019, 100 lizards were experimentally translocated from two state parks in Martin County, where they are abundant, to Hypoluxo Scrub Natural Area in central Palm Beach County, 23 miles south of the nearest remaining population. This county-owned scrub preserve still contains suitable habitat, but scrub lizards had disappeared by 2005, possibly because of feral cat predation.

Selected References

Branch, L. C., A. M. Clark, P. E. Moler, and B. W. Bowen. 2003. Fragmented landscapes, habitat specificity, and conservation genetics of three lizards in Florida scrub. Conservation Genetics 4(2):199-212.

Clark, A. M., B. W. Bowen, and L. C. Branch. 1999. Effects of natural habitat fragmentation on an endemic scrub lizard (Sceloporus woodi): an historical perspective based on a mitochondrial DNA gene genealogy. Molecular Ecology 8(7):1093-1104.

Enge, K. M., B. Tornwall, and B. Bankovich. 2018. Florida scrub lizard status survey. Final Report, Grant Award No. FL-E-F16AP00227. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Wildlife Research Section, Gainesville, Florida, USA. 107pp.

Enge, K. M. 2019. Sceloporus woodi Stejneger 1918, Florida scrub lizard. Pages 399-402 in K. L. Krysko, K. M. Enge, and P. E. Moler, editors. Amphibians and reptiles of Florida. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, Florida, USA.

Hokit, D. G., and L. C. Branch. 2003. Habitat patch size affects demographics of the Florida scrub lizard (Sceloporus woodi). Journal of Herpetology 37(2):257-265.

Jackson, J. F. and S. R. Telford. 1974. Reproductive ecology of the Florida scrub lizard, Sceloporus woodi. Copeia 1974(3):689-694.

McCoy, E. D, P. P. Hartmann, and H. R. Mushinsky. 2004. Population biology of the rare Florida scrub lizard in fragmented habitat. Herpetologica 60(1):54-61.

Tiebout, H. M., III, and R. A. Anderson. 2001. Mesocosm experiments on habitat choice by an endemic lizard: implications for timber management. Journal of Herpetology 35(2):173-185.

Williams, S. C., and L. D. McBrayer. 2015. Behavioral and ecological differences of the Florida scrub lizard (Sceloporus woodi) in scrub and sandhill habitat. Florida Scientist 78(2):95–110.