Snap bean is an important vegetable crop in Florida. It is produced in all regions of the state. Bush snap beans dominate commercial plantings, but pole beans are also produced, primarily in Miami-Dade County. Midwinter bean production, the most profitable for Florida, is centered in the Homestead, southwest Florida, and Belle Glade areas.

Based on the 2012 US Census of Agriculture (NASS, USDA), snap bean is an economically important vegetable crop in Florida with a total of 33,338 acres harvested in 2012. Miami-Dade County ranked second in snap bean production in the United States with a total of 11,126 acres. Because of Florida's warm and wet weather, many diseases affect snap beans. Disease management is an important component in successful snap bean farming. Despite vigorous control efforts, substantial losses in yield and quality can still occur. This publication suggests a sequential disease control program for snap beans in Florida. Postharvest disease problems are addressed only to the extent that they are affected by field practices. The application of the following sequential control program should minimize yield losses for the majority of plantings.

Characteristics of Pathogens Causing Diseases on Snap Bean

Pathogenic microorganisms cause most disease problems in plants. These pathogens are extremely tiny. They cause losses in beans by attacking the pods directly, rendering them unmarketable or unsuitable for consumption by reducing quality. Diseases can also affect other plant parts, reducing plant vigor and carbohydrate production, which causes yield and monetary losses.

The pathogens attacking snap beans can be classified into three major groups: fungi and fungal-like microorganisms, bacteria, and viruses.

Fungi and fungal-like microbes (hereafter referred to as fungi) are microscopic organisms that have often been classified as plants. However, they are sufficiently different from true plants that experts now classify these organisms in unique categories. They do not have true leaves, roots, or stems. Rather, they appear as hyphae (microscopic threads of living matter) that absorb food and water directly into their cells.

Although fungi have cell walls, the chemical composing the wall of many fungal species resembles the chitin in the shells of insects rather than the cellulose in the cell walls of higher plants. Because fungi do not have chlorophyll, they must depend on outside sources of food, including living plants.

Many of the fungi attacking snap beans reproduce by creating large numbers of spores. Some spores are airborne and spread readily by wind or water within and between fields. Some fungal spores or sclerotia (hyphal aggregates), especially those causing root and stem rots, can survive in the soil for one or more years between susceptible crops.

Although most plant pathogenic fungi can directly penetrate plant tissues, some may enter plants through wounds or natural openings such as stomates that allow normal exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between plant cells and the atmosphere.

Bacteria are smaller microorganisms than fungi and are not at all plant-like. They are one-celled, lack chlorophyll, and do not form spores. The major type of reproduction for plant pathogenic bacteria is by simple cell division. They cannot penetrate the plant directly, but must enter the host through a wound or natural opening.

Viruses really should not even be considered "organisms." They are simply very large molecules made up of a nucleic acid (DNA or RNA), with a wrapping or "coat" of protein. New virus particles can only be synthesized within living plant cells. They are much smaller than bacteria and normally require high magnification of electron microscopes to be seen.

Some bean viruses are seed-transmitted. Bean plants from the infected seed serve as sources of infection for healthy plants. The virus may also spread from infected weed hosts growing near bean fields. Aphids, thrips, whiteflies, and other insects are usually responsible for plant-to-plant spread within and between fields. When these insects probe infected plants for food, they may pick up virus particles and infect healthy plants during subsequent feedings.

Disease Development

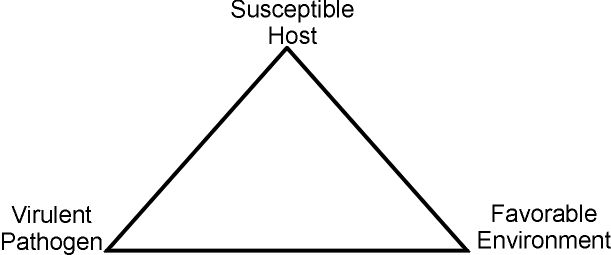

Production of disease symptoms in snap bean plants requires all three components of the disease triangle (Figure 1): a virulent pathogen, a susceptible host, and weather conditions favorable for disease development. If any of these components is missing, plants will not become diseased.

Effective control of snap bean diseases is based upon understanding the concepts described above: the biology of the causal organism, the response of the host to the pathogen, and the interaction of outside forces such as temperature, moisture, and soil type with the living systems involved. A brief outline of the characteristics of the major Florida snap bean diseases is provided in Table 1.

With this essential background information, we can proceed to a sequential disease control program for commercially grown snap beans in Florida.

Suggested Sequential Program for Disease Control

I. Seed Treatment

Snap beans are generally very susceptible to fungi causing damping-off. In order to minimize losses from damping-off, most commercially available bean seeds are treated with fungicides. This is readily apparent by the distinct color imparted to the seed by the fungicide coating applied by the seed supplier. If, by chance, your seed is not treated, consider applying your own seed treatment.

Mefenoxam such as Apron XL® and metalaxyl, including Sebring 318 FS® and Metalaxyl 4.0 ST®, can be applied as a seed treatment for Pythium, Phytophthora, and closely related microorganisms. It is not effective against Rhizoctonia, Fusarium, and other non-pythiaceous organisms. Apron MAXX® (fludioxonil and mefenoxam) as a seed treatment, on the other hand, can control damping-off and seed rot caused by Fusarium, Pythium, Phytophthora, and Rhizoctonia. Neither of these fungicides can be used to control the aerial blight phase of Pythium on mature plants. Please note that extensive use of these products may result in selection of resistant isolates of the pathogens.

Please note that treated seed should never be used as food or fed to animals.

II. Other Pre-Plant or At-Planting Treatments

There are several pre-plant or at-planting chemical options that growers may use. One is primarily an in-furrow spray with mefanoxam and/or pentachloronitrobenzene (PCNB). See labels for details.

III. Specific Cultural Controls

A. Site Selection and Crop Rotation

The susceptibility of snap beans to soil-borne pathogens dictates that growers carefully choose land on which to grow their crops. Fields should be well drained and free of "low spots," where water from rain and irrigation may collect. Populations of disease pathogens and other pests build up quickly in the soil consecutively cropped to snap beans. Therefore, rotation with less susceptible crops or with crops grown in a full-bed fumigated plastic mulch system should be considered if at all possible.

B. Plant Spacing

Based on the work at the Tropical Research and Education Center in Homestead, it is suggested that plant spacing can be a very important tool for managing snap bean diseases. Generally speaking, higher yields are achieved by increasing plant populations per acre. Plant populations can be increased by decreasing the spacing between rows and/or the spacing between individual plants in a row. Decreasing the between-row spacing for the cultivar 'Sprite' from 36 to 18 in. generally resulted in increased yields with no adverse effects on disease incidence. However, close in-row spacing (e.g., 1.5 vs. 4.5 in.) was associated with dramatic increases in disease levels, especially white mold caused by . Therefore, the optimum arrangement of snap bean plants for maximum yields and best disease control is closer between-row spacing (e.g., 24 in.) and wider in-row spacing (e.g., 3.5–4.5 in.). Since white mold typically becomes serious during seasons when cool, moist conditions occur and is affected greatly by plant spacing, these horticultural recommendations are particularly appropriate for snap bean crops grown in the cool months of the year (i.e., December–March in Miami-Dade County).

C. Purchase of Certified Seed

The exclusion of seedborne pathogens is extremely important in the control of several snap bean diseases, including common bacterial blight, halo blight, bacterial brown spot, anthracnose, and bean common mosaic. Seed produced in arid regions such as the American West is less likely to be contaminated with these pathogens. Idaho and other western states, which have extensive seed industries, often have rigid programs for seed certification. While they cannot guarantee absolutely clean seed, they have a fine record for minimizing problems of seedborne pathogens.

Cultivation or any other movement of equipment or people within fields should be avoided when plants are wet. Disease-causing organisms, especially bacteria, are readily spread mechanically when there is moisture on the leaves. Farm equipment should periodically be decontaminated to prevent between-field spread.

Plants should be grown under optimal horticultural conditions. Vigorous, healthy plants that are properly fertilized and watered are less likely to be affected by many diseases. In particular, excessive nitrogen can make beans more susceptible to bacterial disease. If fertilizer is applied at lower than optimum rates, however, beans will be more susceptible to Alternaria leaf and pod spot.

IV. Application of Foliar Fungicides

Periodic application of fungicides is important for disease control in snap beans. Ground or aerial application can be used, but the former is much preferred because it leads to superior pesticide penetration of the plant canopy and better coverage of lower leaf surfaces.

Attention to application technique is as important as the choice of materials in achieving adequate disease control. A "typical" spray application on fully grown bush snap bean plants would be done with a tractor-mounted boom sprayer at 200–275 psi pressure and 100 gal/acre of finished spray. Proper equipment calibration uses a tractor speed of about 3 mph. At this speed, one should be able to comfortably walk behind the tractor. At this speed, most diseases can be adequately controlled with one application of fungicide per week. A shorter interval (e.g., every 5 days) may be needed at the times of the year when rust is known to occur.

Care must be taken to ensure that nozzles work properly, strainers are clear, and nozzle arrangement allows for adequate coverage. Consider using drop nozzles to control disease problems on pods such as white mold and Alternaria leaf and pod spot. The air in the canopy must be completely displaced by a fine mist of fungicides to prevent disease outbreaks that can begin deep within the canopy.

Since fungicides are primarily preventative (i.e., they must be applied before the pathogen arrives on the foliage), timing of fungicide applications is very important to ensure effective control. If fungicide sprays start after a disease has been discovered, it may be impossible to stop. This is particularly true for rust in snap beans. If fungicide sprays are delayed until rust first appears, severe economic losses can occur.

Chlorothalonil is an effective, broad-spectrum fungicide labeled for snap beans and is an important component of a control program. When rust threatens, sulfur can be tank-mixed with chlorothalonil for enhanced control.

It is extremely important that specific chemical treatments be applied for white mold control. Two applications of Rovral® 4F (iprodione) can be made to snap beans for control of this disease. The second application may be needed no later than at peak bloom. Topsin-M® (70% WP) (thiophanate-methyl) can be applied at 10%–30% bloom and again 4–7 days later (or use a single application at 50%-70% bloom). These compounds also may help control other foliar diseases, including gray mold and anthracnose.

When the specific bloom sprays listed above are applied for white mold, it is important that chlorothalonil be included in the tank mix in order to maintain control of other diseases, especially the pod-blight phase of Alternaria leaf and pod spot. Sprays of copper bactericides may also be warranted if evidence of bacterial diseases is found.

Bean golden mosaic (BGMV) is a devastating virus disease of snap bean, especially in southern Florida. It has caused severe damage in many fields, particularly in Miami-Dade County, sometimes forcing growers to abandon entire plantings of snap beans. The virus is transmitted by the silverleaf whitefly, which is ubiquitous in Miami-Dade County.

Successful management of BGMV requires strict adherence to an integrated pest management program. Isolate bean fields as much as possible from other susceptible crops that might serve as virus reservoirs. These include tomato, squash, okra, and many ornamental crops (e.g., poinsettia, hibiscus, and lisianthus). Many weeds may also harbor the virus and its vector.

Scout fields intensely and spray effective insecticides to reduce whitefly populations. Promptly destroy crops once symptoms are discovered so that virus titer and whitefly populations do not build up and provide a source of inoculum for newly planted crops.

Readers are encouraged to consult their county Extension agents, the Vegetable Production Handbook for Florida, or the Florida Plant Disease Control Guide for current, specific fungicide recommendations. They also may want to use the plant pathology fact sheets listed in Appendix I for information on accurate diagnosis of several bean diseases.

Appendix I

Kucharek, T. Rhizoctonia seedling blights of vegetables and field crops. PP-1. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Kucharek, T. Stem rot of agronomic crop and vegetables (southern blight, white mold). PP-4. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Pernezny, K., and Jones, J. B. Common bacterial blight of snap bean in Florida. PP-62. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Pernezny, K., and Kucharek, T. Rust disease of several legumes and corn in Florida. PP-37. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Pernezny, K., and McMillan, R. T., Jr. Alternaria leaf and pod spot of snap bean in Florida. PP-61. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Pernezny, K., and Purdy, L. H. diseases of vegetable and field crops in Florida. PP-22. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Pernezny, K., and Stall, W. M. Powdery mildew of vegetables. PP-14. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.