Introduction

When Extension professionals work to encourage behavioral changes in their community through educational programming, they may already be using some elements of social marketing. A social marketing approach applies elements of traditional marketing in order to encourage behavior changes that benefit the community's health and wellness, the environment, or financial well-being. Social marketers recognize that providing education alone does not necessarily result in a change in behavior. Instead, social marketers have developed an approach that addresses the barriers to behavior change and makes it convenient, easy, and socially desirable. This publication was developed to help Extension professionals and other practitioners working in landscape-related areas to integrate social norms into their programming.

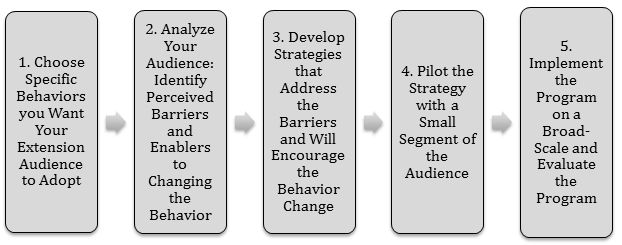

The social marketing process involves first selecting what behavior change is desired and researching how the audience feels about that behavior (Figure 1). Extension educators can use an understanding of their clients' reservations and inclinations toward a behavior, or their benefits and barriers, to develop strategies that encourage behavior change. Some of the common strategies used by social marketers to encourage new behaviors or behavior change include prompts and reminders, incentives, and changing social norms. These strategies may be piloted on a small scale, modified if necessary, and then implemented on a large scale and further evaluated. This publication's purpose is to describe the use of social norms as a social marketing strategy and make recommendations for applying social norms as a tool in Extension programming.

Credit: Adapted from McKenzie-Mohr, 2011

What are Social Norms?

Normative beliefs, or social norms, are how people think certain behaviors are viewed by the individuals and groups around them (Ajzen, 1991). Norms are the beliefs that people often share about what others are doing and what other people may approve or disapprove. (For an in-depth description of these types of norms, see Social norms for behavior change: A synopsis). When individuals assume that "everyone recycles," "no one obeys the speed limits on the interstate," or "most college kids drink alcohol," then they are relying on norms. If someone avoids littering in front of others because they think their peers would disapprove, they are conforming to normative behaviors. Essentially, social norms are reflected by what individuals believe their peers do and think. Viewed through the lens of Extension, clients' peers are the people important to them. Extension professionals must consider how their audiences feel about what they are being encouraged to do and think of what their audiences' peers are doing and thinking related to the behavior as well.

A number of recent studies have pointed to norms as a major factor in landscaping choices. One study that explored landscape management practices in Ohio revealed that whether a neighbor applies lawn chemicals is a major factor in whether a resident does the same (Blaine et al., 2010). Clayton summarized it best: "(t)he promotion of a cultural norm, through mass media and marketing material, that focuses on the desirability of a neat and weed-free lawn rather than a beautiful outdoor landscape, is almost certainly responsible for yard care practices that not only threaten the environment but also reduce homeowners' abilities to enjoy the benefits of nature" (2007, p. 223). Other recent research has shown perceptions of what others do seems to influence behaviors more than perceptions of what others approve of, and norms from someone’s closest groups of people (e.g., friends and family) seem to matter most (Warner, 2021).

Social scientists have conducted other interesting experiments on normative behaviors related to student alcohol (Perkins, 2002) and littering (Cialdini et al., 1990). To understand how people are influenced by the behavior of others, Cialdini et al. placed flyers on car windshields and found that about a third of drivers tossed the flyer on the ground. However, if the drivers saw a person pick up and dispose of a piece of trash (actually a researcher who was part of the experiment), they were much less likely to throw their flyer into the street. Perkins wrote about the negative effect caused by college students' perceptions about how much others were drinking, and problem drinking was exacerbated in cases where students thought their peers were drinking heavily. These experiments demonstrate the powerful influence of norms over behavior.

Norms are proven to be good predictors of what people will intend to do, and ultimately, how they will act. When educators take the time to understand their audiences' social norms, they can use this information to provide programs that are highly valuable to their clientele and more likely to result in the intended outcomes. A social norm—even if it is incorrect (e.g., actual alcohol consumption was lower than fellow students believed)—can influence behaviors.

Social Norms as a Strategy to Encourage Behavior Change

Applied to Extension programming as a strategy, social norms can be emphasized to encourage behavioral change. Using this approach, the Extension agent highlights that a positive action (such as keeping grass clippings on the lawn) is approved of and regularly done by one's neighbors (or other important reference groups), while negative actions (such as dumping grass clippings in the storm drain) are disapproved of and avoided by others. This emphasis on peers who are doing a positive action will increase the likelihood that the audience would adopt or change a particular behavior.

A recent study found strong associations between a homeowner's landscaping practices and their neighbor's landscaping practices. "One of the best predictors of whether a respondent employs a lawn care company to apply chemicals, does it himself, or has an acquaintance do it is what the neighbor is believed to do" (Blaine, et al., 2012, p. 266). A social norms approach in this situation would dictate that an Extension professional could publicize the neighbors who are doing the desirable behavior, such as spot treating with pesticides, as opposed to applying blanket chemical applications for pest control. The Extension professional might put signs in the yards where this practice is done. As neighbors become more aware that their peers are engaging in the behavior and that they approve, they will become more likely to do the same. This is a simple example of emphasizing positive social norms to achieve behavior change.

Gainesville Regional Utilities (GRU), an electric company located in Florida, previously included inserts in their monthly utility bills that read, "Gainesville homes use 25% less water than they did a decade ago." The inserts give residents a "peek" into their neighbors' water usage habits. When residents become aware that the community around them is conserving water (social norms), then they are more likely to do the same. It is recommended that Extension professionals work with local media and organizations to publicize norms to encourage sustainable behaviors. In the case of less visible behaviors, such as water usage, media can play a critical role in making certain norms more visible.

Examples of Social Norms

The following studies are just a few examples of the effectiveness of this strategy.

- Nassauer et al. (2009) studied residential landscape preferences in the context of cultural and neighborhood norms. They found that homeowners preferred landscapes that matched broad cultural norms and that their preference for matching neighborhood norms outweighed their preference for cultural norms. Further, the individuals who preferred environmentally sustainable designs were those whose neighbors had that type of landscape (Nassauer et al., 2009). The researchers suggested that environmentally beneficial landscape practices therefore be promoted at the neighborhood level, as opposed to the individual or large-scale community level.

- People were more likely to litter when they saw there was already a lot of litter on the ground; they were even more likely to litter if they actually saw someone littering (Cialdini et al., 1990).

- One study found that social norms were positively associated with intentions to install a rain garden to protect local lakes (Shaw et al. 2011). In other words, people who agreed that friends, family, and neighbors would approve installing a rain garden were more likely to plan to do so than those who did not. This kind of social support is often needed to encourage new behaviors.

Unlimited possibilities exist for applying norms to educational initiatives. Table 1 presents a few suggestions for applying social norms to Extension programming to encourage sustainable landscaping behaviors.

Adopting Norms as a Strategy

Most Extension professionals have heard "but this is how we've always done it" when introducing something new. A key issue in changing behaviors is that it means challenging an existing norm, which often results in resistance to change. When advocating for change, it is important to keep in mind that half of a given population will generally be resistant to change; about half of a population tends to be late adopters or laggards, which are the very last adopters of something new (Rogers, 2003). When introducing new ways of doing things, an Extension professional is asking clients to substitute a new behavior for an existing norm. This is very challenging—not only because people tend to dislike change in general—but because people often do things because they are the norm, and they are being asked to change the way they think of "what is normal".

There are two types of people who play an important role in community change—opinion leaders and early adopters. Opinion leaders are the people in the community who have great influence over people's behavior and attitudes (Rogers, 2003). While half of a population may be considered late adopters, a smaller percentage is typically considered early adopters, who are people who readily adopt an innovation before the majority of a population does (Rogers). Early adopters are integrated in the community, well respected, and they are generally seen as role models by their peers (Rogers). Not surprisingly, early adopters are frequently also opinion leaders.

The success in using social norms to encourage behavior change lies in the participation of early adopters and opinion leaders. When applying the social norms strategy to Extension programs an agent needs to identify the opinion leaders and early adopters within their target audience. Next, the agent would recruit some of the opinion leaders and early adopters as examples of the new norm. Then, they can incorporate these examples into their educational programming.

Extension educators should use norms when promoting changes that are viewed positively by the target audience. As mentioned earlier, social marketing and its various tools require a research-based approach to programming. The key to social marketing is understanding an audience's feelings and perceptions towards the behavior of interest. This can be accomplished with a thoughtful needs assessment as part of the Extension program planning process. There are several different approaches to needs assessment that include audience self-reporting, surveys, focus groups, secondary data, advisory committees, observation, and interviews with key leaders (Caravella, 2006; Gouldthorpe & Israel, 2013). These research methodologies allow Extension professionals to gain critical insight into their audience's sentiments towards specific behaviors and issues, including whether the behavior is viewed in a positive light. If the behavior is not seen as a positive change, or a lack of support for the behavior is present, then social norms may not be the most appropriate approach to change.

With thoughtful planning, norms are easy to incorporate into existing Extension programs and can increase the occurrence of behavior changes. The following is a summary of recommended best management practices for using this strategy.

Best Practices for Using Social Norms to Encourage Behavior Change1

- Research the audience to understand how they view the behavior and gauge existing social norms

- Choose behaviors that are perceived in a positive light by participants

- Recruit early adopters and opinion leaders as examples of the norm

- Make the norm noticeable to the target audience

- Consider promoting the norm on a neighborhood scale

- Emphasize the norm at a time and place where the behavior would take place

- Strategize to make less visible behaviors (i.e. irrigation water use) visible

- Use messages to demonstrate social approval for the behavior or disapproval for not following the behavior

- Partner with local media to use social norms to alter behavior

- Use norms to encourage positive behaviors (this is more effective than using norms to discourage negative behaviors)

1Adapted from Bator & Cialdini (2002;) McKenzie-Mohr (2011); and Nassauer et al. (2009).

Conclusion

Extension professionals can use their programs to encourage behavior change among their clients by borrowing different tools from the field of social marketing. Using social norms is an effective tool that should be incorporated into many Extension programs. When used correctly, social norms communicate that a particular behavior is usual and expected, which increases the likelihood that clients will adopt a specific behavior. Social norms are a proven technique for increasing the percentage of an audience that adopts new behaviors. Like identifying target audiences and reducing barriers to adoption, using social norms allow Extension professionals to make behavior change easy, fun, and socially desirable through social marketing. Extension professionals wishing to incorporate social norms and other social marketing tools into their existing programming can learn more from the following resources:

Web Resources

Fostering Sustainable Behavior: Community-Based Social Marketing (https://cbsm.com/book)

On Social Marketing and Social Change News and Views on Social Marketing and Social Change: (https://socialmarketing.blogs.com)

Tools of Change: Proven Methods for Promoting Health, Safety, and Environmental Citizenship (https://toolsofchange.com/en/home/)

Water Words that Work (www.waterwordsthatwork.com)

University of Florida IFAS Electronic Database Information Source (EDIS) Publications: (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu).

Making Your Community Green: Community Based Social Marketing for EcoFriendly Communities (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/uw263).

Social Marketing in the Wildland-Urban Interface. (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/fr254).

Using Audience Commitment to Increase Behavior Changes in Sustainable Landscaping (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/wc154).

References and Further Reading

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Bator, R. J., & Cialdini, R. B. (2002). New ways to promote proenvironmental behavior: The application of persuasion theory to the development of effective proenvironmental public service announcements. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 527–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00182

Blaine, T. W., Clayton, S., Robbins, P., & Grewal, P. S. (2012). Homeowner attitudes and practices towards residential landscape management in Ohio, USA. Environmental Management, 50(2), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-012-9874-x

Caravella, J. (2006). A needs assessment method for extension educators. Journal of Extension [Online], 44(1), 1TOT2. https://archives.joe.org/joe/2006february/tt2.php.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015–1026.

Clayton, S. (2007). Domesticated nature: Motivations for gardening and perceptions of environmental impact. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(3), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.06.001

Gouldthorpe, J. L., & Israel, G. D. (2013). The savvy survey #1: Introduction. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/pd061.

McKenzie-Mohr, D. (2011). Fostering sustainable behavior (3rd ed.). Canada: New Society Publishers.

Nassauer, J. I., Wang, Z., Dayrell, E. (2009). What will the neighbors think? Cultural norms and ecological design. Landscape and Urban Planning, 92(3-4), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2009.05.010

Perkins, H. W. (2002). Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Suppl. 14, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Shaw, B. R., Radler, B. T., Chenoweth, R., Heiberger, P. & Dearlove, P. (2011). Predicting intent to install a rain garden to protect a local lake: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Extension [On-line], 49(4) Article 4FEA6. https://archives.joe.org/joe/2011august/a6.php

Warner, L. A. (2021). Who conserves and who approves? Predicting water conservation intentions in urban landscapes with referent groups beyond the traditional ‘important others’. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 60, 127070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127070

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Alexa Lamm and Glenn Israel for their helpful suggestions on an earlier draft.