Introduction

Palms growing in the landscape and field nurseries are susceptible to a wide range of diseases and disorders. Diagnosis of a particular palm problem often requires either a comprehensive understanding of all of the possibilities or a systematic key to help the diagnostician focus on the cause of the problem. Keys are now available to help diagnose the most common diseases and disorders affecting palms. Some are only available on the web and others are also available as free apps for your mobile devices. These keys include damage caused by insects, and there is also a key for identifying insect pests of palms. The keys also have links to fact sheets about each specific problem or pest.

-

UF/IFAS FLREC Palm Problems Key: http://flrec.ifas.ufl.edu/palmprodpalm-problems-key/

-

LUCID KEYS: A Resource for Cultivated Palms from the United States and Caribbean

-

Resource home page: http://itp.lucidcentral.org/id/palms/resource/index.html

-

Screening Aid to (Insect) Pests: http://www.idtools.org/id/palms/sap/index.php

-

Available from iTunes (iOS) and Google Play (Android)

-

Symptoms of Diseases and Disorders: http://itp.lucidcentral.org/id/palms/symptoms/

-

Available from iTunes (iOS) and Google Play (Android)

-

Symptoms of Diseases and Disorders: http://itp.lucidcentral.org/id/palms/symptoms/

-

Available from iTunes (iOS) and Google Play (Android)

The information in this document includes tips to determine when laboratory diagnostics may be useful and how to interpret and/or integrate field and laboratory diagnoses. References regarding palm horticulture, physiological disorders (e.g., nutrient deficiencies), diseases, and insects are listed at the end of this document.

A Dead Palm Tells No Tales

Scientists and palm specialists often receive photographs of dead palms, with no other accompanying material and with the following question attached: "What killed my palm?" In most cases, it is not the least bit obvious what has killed the palm! Diagnosticians (be it in the field or in the laboratory) need clues. The best clues come from palms that are still living and from the people who are growing the palms (especially if they have been closely observing the palms). Background information can be critical for making the correct diagnosis. This includes information about the palm itself, its surrounding environment, maintenance practices, and also recent weather events.

Even with plenty of clues, it still may not be possible to determine exactly what is affecting the palm. We can only make an educated guess. Diagnosing palm problems can be as much an art as it is a science, and experience is invaluable. Often, the field or landscape observation allows you to narrow the cause of the problem to two or three possibilities. Then, with a palm autopsy or lab diagnosis, you may be able to determine the exact cause of the problem.

Field Diagnosis vs. Laboratory Diagnosis

Since few people have immediate access to analytical laboratories, the diagnostic keys are based solely on visible symptoms. Fortunately, visual symptoms are sufficient to diagnose many palm problems. Visual symptoms are also the first step in determining which diagnostic lab to use for further analysis, and which tissue should be sampled for analysis. Table 1 provides guidelines regarding tissue to sample. For most plant diseases, plant diagnostics is not nearly as sophisticated as human medical diagnostics. A laboratory analysis should always be used in conjunction with the field diagnosis of the problem. Never rely on a laboratory diagnosis without also making a good faith attempt at the field diagnosis. The two diagnoses should agree.

Just because a laboratory report suggests deficiencies of one or more nutrient elements or the presence of one or more potential pathogens does not mean that those deficiencies or pathogens are the actual cause of the particular problem. "False positives" are common and often misleading. This is one weakness of laboratory diagnostics when used as the sole method of diagnosis. In the case of palm diseases, "false negatives" are also a common problem, especially when the wrong tissue is sampled or a sample of poor quality is submitted to the laboratory. If the two diagnoses (field and lab) do not agree, then re-examine the problem to determine which diagnosis is more likely to explain the symptoms being observed (compare to descriptions and photos in reference materials), and if you sampled the correct material for the laboratory diagnosis. Alternatively, you may need to start at the beginning, as neither diagnosis may be correct.

Laboratory Disease Diagnosis

A laboratory disease diagnosis may be required to confirm the field diagnosis, as it may not be readily apparent which pathogen is causing the symptoms observed in the field. Sometimes a laboratory diagnosis is necessary because two diseases have identical symptoms. For example, Fusarium wilt and petiole (rachis) blight of Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis) have similar symptoms, but one is lethal (Fusarium wilt) and one is not. If confirmation of a field disease diagnosis is necessary, it should be conducted by a qualified plant-disease diagnostic laboratory. For example, molecular tests are necessary to confirm Fusarium wilt, lethal yellowing, and Texas Phoenix palm decline, but only the University of Florida currently offers these services in Florida (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/sr007).

Sampling the correct tissue is critical for an accurate laboratory diagnosis. For example, lethal yellowing is confirmed from internal trunk corings, while petiole (rachis) blight pathogens only infect the palm leaf petiole or rachis. In both cases, sampling leaflet tissue of a palm affected by either of these diseases would have yielded a false negative. Thus, it is imperative to make the field diagnosis as accurate as possible in order to determine which tissue to sample. Many "potential" plant pathogens are naturally part of the palm environment, so it is easy to isolate these potential pathogens rather than the actual pathogen causing the symptoms observed. The laboratory is analyzing the tissue that you provide. Sampling the proper tissue and providing adequate background information on the problem increases the likelihood of obtaining an accurate diagnosis. A good series of photographs illustrating the problem is always helpful.

One common error in diagnosing palm problems is to sample roots. In the landscape and field nursery, root rots of palms are uncommon, and are usually the secondary result of a palm being planted incorrectly or in the wrong environment. Examples include planting Phoenix dactylifera in soils that are routinely water-logged or planting any palm too deep. A diagnostic laboratory will usually be able to isolate potentially pathogenic fungi from roots, but these fungi are seldom the primary cause of the problem observed. This is an important distinction for management purposes, as one needs to first correct the primary cause, if possible. Likewise, soil sampling for potential pathogens is not recommended because there are always potential pathogens in the soil. Root rots of palms growing in containers are more likely to occur because of the poor soil aeration, but even in containers the root disease is usually secondary.

Sometimes it is not possible to make a confirmation of a field diagnosis until a dead or dying palm is cut down. For example, palms affected by Ganoderma butt rot may die without producing conks (basidiocarps) from the lower trunk area. However, when the palm is cut down and multiple cross-sections are made of the trunk, the disease will be easily confirmed based on the pattern of discoloration within the trunk, and without the necessity of a laboratory diagnosis.

Leaf Nutrient Analysis

Most nutrient deficiency problems can be readily diagnosed by visual symptoms alone. For most palm species, diagnosis should rely on visual symptoms rather than a leaf nutrient analysis. Baseline data for nutrient sufficiency has been developed for only a few palm species. Therefore, without a comparison to a known nutrient-sufficient palm of the same species, a leaf nutrient analysis can be misleading.

There are situations where multiple deficiencies may be present on a single palm. Symptoms of these deficiencies may be present on different parts of the palm (e.g., old vs. new leaves), but may occasionally be superimposed on the same tissue. A common example of the latter is potassium and magnesium deficiency symptoms, both being present to some degree on the older leaves of a palm. For these situations, leaf nutrient analysis can be useful for distinguishing multiple deficiencies where the symptoms of one deficiency may mask those of another.

Leaf analysis can also be used to confirm or clarify a diagnosis based on visual symptoms. However, there are exceptions. For example, leaf analysis is not particularly useful for diagnosing iron deficiency in any plant, and leaf analysis may not accurately assess the boron sufficiency status of a palm at any given time, due to the often transient nature of boron deficiency. However, it is useful for confirming chronic boron deficiency when symptoms are present on multiple leaves.

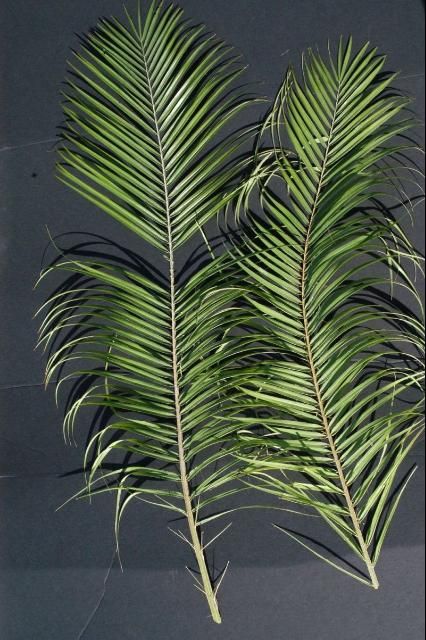

In order to obtain useful results from a leaf analysis, the proper leaves must be sampled. Leaf nutrient analyses are based on samples consisting of several leaflets (pinnate-leaved palms) or leaf segments (fan-leaved palms) taken from the center of the youngest, fully expanded leaf (Figures 1 and 2). Depending on the nutrient deficiency, this may or may not be the leaf exhibiting symptoms. In pinnate leaved palms, this youngest, fully-expanded leaf should have all of its basal leaflets (or spines in some species) expanded out and perpendicular to the petiole axis, as in older leaves (Figure 1).

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. K. Broschat, UF/IFAS

Leaf Disease vs. Nutrient Deficiency

To complicate matters even further, it is possible to have both a nutrient deficiency and a leaf spot disease. Furthermore, some nutrient deficiencies look like a leaf spot disease. If you cannot decide which problem you are observing, then collecting samples for both a disease diagnosis and a leaf nutrient analysis may be necessary. However, this will require duplicate samples and may require sampling different tissue on the same plant. As explained above, leaf nutrient analysis is based on leaflets from the youngest fully expanded leaf. Leaf disease samples should be the leaves exhibiting the leaf spot or leaf blight symptoms.

Soil Nutrient Analysis

Soil nutrient analysis has often been employed in the diagnosis of plant problems in the landscape and field nursery. Unfortunately, this technique has limited value for this purpose and often leads to erroneous conclusions. Just because a nutrient element is found to be "deficient" in the soil does not mean that the plant is unable to extract sufficient amounts of that element from the soil. Alternatively, a palm may be suffering from a deficiency of an element that is present in "sufficient" levels according to soil tests.

Soil analysis can be useful for diagnosing problems such as high soluble salts, a disorder with symptoms very similar to those of chemical toxicities or even potassium deficiency in some species. Soil analysis may also provide useful information regarding soil pH, which could affect your choice of corrective fertilizers or explain why a deficiency is occurring. For example, manganese availability in the soil is soil pH dependent.

When collecting soil samples for laboratory analysis, it is best to scratch away the mulch or other surface covering and obtain a cup or more of soil from the top 4 to 6 inches of the soil profile. Sample several areas under the canopy of a single palm, or from under the canopies of several palms, if they are all affected by a single problem. These samples should be thoroughly mixed, and about one cupful of the mixture taken to a soils laboratory for analysis.

More Information

Once a diagnosis is made, treatment for that particular problem can be obtained from the appropriate UF/IFAS Extension documents on the web. These documents contain discussions and illustrations of the palm diseases, physiological disorders, and insect problems included in the key and should be used in conjunction with the key. A set of plastic-coated cards that illustrates the more common palm diseases and disorders is also available. You should also consult with your local UF/IFAS Extension office for local updates. (Link to county offices and maps at http://solutionsforyourlife.ufl.edu/map/index.html.)

Broschat, T.K., and A.W. Meerow. 2000. Ornamental Palm Horticulture. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. 800/226-3822. http://www.upf.com.

Broschat, T.K., and M.L. Elliott. 2009. Disorders and Diseases of Ornamental Palms 2nd ed. SP360. (Spanish version available SP-360S) UF/IFAS Extension, Gainesville, FL. This is a set of plastic-coated, color cards (3 x 4 inches) with 45 photos of common disorder and disease symptoms. 800/226-1764 (credit card orders only) or http://ifasbooks.ufl.edu - under "Horticulture and Plant Disease."

Elliott, M.L., T.K. Broschat, J.Y. Uchida, and G.W. Simone, eds. 2004. Compendium of Ornamental Palm Diseases and Disorders. St. Paul, MN: APS Press. 800/328-7560. https://my.apsnet.org/APSStore/Product-Detail.aspx?WebsiteKey=2661527A-8D44-496C-A730-8CFEB6239BE7&iProductCode=43143 [also on CD].

EDIS (electronic publication site for UF/IFAS information) has publications on palms at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Type "palm" into the search engine. Many of these publications are new as of 2005. A few are major revisions. As new information becomes available, these publications are updated and new ones are added.

Howard, F.W., D. Moore, R.M. Giblin-Davis, and R.G. Abad. 2001. Insects on Palms. Oxon, UK: CABI Publishing. North American publisher is Oxford University Press. 800/451-7556 ; 954/981-2821. http://www.oup.com/us.

Meerow, A. W. 2006. Betrock's Landscape Palms. Betrock Information Systems, Inc., Davie, FL. 800/627-3819. http://www.betrock.com. This is an updated version of Betrock's Guide to Landscape Palms also on CD.

Meerow, A. W. 2005. Betrock's Cold Hardy Palms. Betrock Information Systems, Inc., Davie, FL. 800/627-3819. http://www.betrock.com.

Florida Extension Plant Disease Clinic Network. General information about the UF/IFAS clinics at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SR007. Pricing is available at https://plantpath.ifas.ufl.edu/misc/media/Pricing%20guide%20by%20test%20type%201-12-22.pdf [2 March 2022].

UF/IFAS Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center web page on Palm Production and Maintenance has links to EDIS publications and additional files on "hot topics" at http://flrec.ifas.ufl.edu/ - then click on "Palm Production and Maintenance."

Featured Creatures is the UF/IFAS Department of Entomology & Nematology/DPI website at http://entnemdept.ifas.ufl.edu/creatures/.