Aging in the 21st Century

In 2016, there were 49.2 million US residents who were 65 years old or older (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017b). By 2050, the nation's population aged 65 and over is projected to reach close to 84 million (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017b). The over-85 population will increase from about 6 million to 14.6 million in 2040 and 18 million in 2050 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014; ACL, 2016). In 2015, more than one fifth of Americans aged 65 or older were members of racial or ethnic minority populations. The percent of older adults in these groups will increase in the coming years (ACL, 2016). Currently, Florida has the highest percentage of full-time and seasonal residents over the age of 65 (19.4%) in the US, and 10.6% of older adults in Florida live in poverty (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017a; FDEA, 2016). Older Floridians, their families, and communities face many issues related to aging. Aging in the 21st Century is an eight-topic series that addresses issues such as:

-

Health and medical care

-

Family relationships

-

Economic concerns

-

Caregiving

-

Home modifications

-

Retirement

-

Nutrition and diet

This fact sheet focuses on the way aging affects nutrition and diet, and choices that older adults can make to improve or maintain their health and well-being as they age.

Credit: diego_cervo/iStock/Thinkstock

What You Will Learn

-

Physiological Changes: What are the main changes in the body that affect nutrition during older adulthood?

-

Socioeconomic Changes: What social and financial changes can interfere with healthful nutrition during older adulthood?

-

Focus on Nutrients: What nutrients are most critical during older adulthood, and how can they be incorporated into a healthful eating plan?

The Importance of Eating Well

Good nutrition is important throughout life, starting even before we are born. However, during certain stages of life, such as infancy, pregnancy, and older age, having good eating habits is especially critical. A healthful eating pattern can help people age well by:

-

supporting positive nutritional status;

-

aiding in weight management;

-

promoting a healthy immune system;

-

decreasing risks of infection, illness, falls, and chronic diseases; and

-

maintaining digestive health.

A number of age-related factors can adversely affect food choices of older Americans. Nutrition educators provide information to older adults that can help them make healthy food choices, and, when necessary, direct them to programs that provide additional assistance. These programs can help older adults in need improve their nutritional health, reduce risk of chronic diseases and conditions, and maintain good quality of life.

Physiological Changes

As people age, their bodies often change in ways that can affect their nutritional status and eating habits. This is important because eating habits affect nutritional status and overall health. The following are some of the major physiological changes experienced by older persons and their potential nutrition-related consequences or health risks. This information can be used to explain how changes in seniors' bodies affect their nutrient needs and overall health.

Change: Decreased Lean Body Mass (including muscle, bone, connective tissue, organs, and water)

• Increase in obesity risk, if energy intake is not decreased in later years

• Decreased strength—extreme loss of skeletal muscle and muscle strength is called sarcopenia

• Increased risk of falls and bone fractures

-

Increased risk of dehydration

Change: Increased Body Fat

• Increased risk of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, which may result in development of diabetes

Change: Decreased Immune Function

• High incidence of infection

• Increased risk for hospitalization

Change: Decreased Sense of Taste and Smell

• Decreased food intake, which can affect nutritional status

-

Increased risk of foodborne illness

• Poor quality of life

*If consumers experience a change in their sense of taste or smell with a new medication, they can ask their doctor if a different medication can be prescribed.

Change: Impaired Vision

Impacts ability to:

• shop for food;

• read food labels and recipes;

• prepare foods;

• clean the kitchen (and keep food safe); and

• visit congregate nutrition site or participate in other community activities.

Change: Decreased Saliva Production

• Reduced taste perception

• Impact on chewing and swallowing

• Decreased oral digestion of food

• Increased risk of gum disease and tooth loss

• Limited food choices, which can reduce diet quality and nutritional status

Change: Decreased Intestinal Motility

• Decreased food intake

• Constipation

Adequate fiber intake can help to maintain normal intestinal functioning.

Change: Decreased Lactase in Small Intestine

• Decreased ability to digest lactose in milk and milk products.

Older adults with lactose intolerance may limit milk and other good calcium sources in their diet, leading to increased risk of bone loss, fractures, and falls. Persons with lactose intolerance can choose lactase-treated milk or milk substitutes that are fortified with calcium and vitamin D. Taking a calcium/vitamin D supplement can help ensure adequate intake of these nutrients. Many persons with lactose intolerance can tolerate small quantities of milk at meals. Yogurt is often well tolerated in small amounts, and hard cheeses do not contain lactose.

Socioeconomic Changes

Two major socioeconomic changes that can markedly affect eating patterns and nutritional status are social isolation and limited income.

Social Isolation

As people age, they are at increased risk for being socially isolated. They may face the death of their spouse and/or other loved ones and friends. Retired people may lose contact with former colleagues and spend increasing amounts of time alone if they are not involved in community groups.

Physical restrictions may limit participation in activities that would otherwise keep older persons socially involved.

Social isolation is associated with increased risk for food insecurity among older persons, especially those with limited financial resources. This may be related to the inability to shop for and/or prepare food, inadequate resources to purchase food, and decreased appetite.

Older persons who eat alone typically consume fewer calories, and they may have a less varied diet than those who eat with other people. This can place them at risk for poor nutritional status and its associated health consequences.

For some older people, social isolation leads to depressive symptoms, such as lack of interest in usual activities, or to clinical depression. In addition to its effect on appetite, depression can cause confusion, memory loss, and other debilitating conditions. It is critical for older persons experiencing these symptoms to be diagnosed and, if necessary, treated for depression. Getting proper treatment can help improve food intake, nutritional status, and overall quality of life (Eskelinen, Hartikainen, & Nykänen, 2016).

Participating in Extension education programs, volunteering, being involved in religious activities, and attending congregate nutrition sites are a few ways that older persons can stay involved in community life.

Credit: Jacob Wackerhausen/iStock/Thinkstock

Limited Income

The poverty rate for persons 65 and above was 9% in 2016, representing 4.6 million persons. Women, older adults living alone, seniors living in the South or in large cities, rural areas, and small towns, and Latino or African-American seniors are more likely than others to live in poverty (US Census Bureau, 2017a). Limited income may lead to inadequate food intake due to lack of money available to purchase food. In 2015, 6.1% of Americans age 70 years and older had low to very low food security due to lack of resources (Strickhouser, Wright, and Donley, 2015). These individuals often have less nutritious diets or rely on food assistance programs or emergency food sources to have adequate food. An insufficient diet contributes to poor nutritional status and is associated with adverse health effects, such as bone loss and fractures, infection, and chronic diseases.

Older persons with limited means should be encouraged to participate in programs such as the Older Americans Act Nutrition Program (congregate nutrition sites and home-delivered meals, such as Meals on Wheels), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly called Food Stamps), and other programs available in their communities (Bobroff, 2016).

Focus on Nutrients

As people age, it becomes critical for them to select a diet rich in nutrient-dense foods. The need for energy (calories) decreases with age, while most other nutrient requirements remain the same or actually increase. Making healthful choices for a nutritious diet can be a challenge when the quantity of food eaten is limited due to lower energy needs.

This section focuses on some of the nutrients that are critical for older persons. Older adults may want to pay special attention to their intake of these nutrients due to increased need, low typical intake, or physiological changes that affect nutritional status.

Energy

With increasing age, lean body mass decreases and metabolism slows. Starting around the age of 30, people experience a decline in the energy requirement that continues with every passing decade of life. In addition, physical activity often decreases as people age, further lowering the energy requirement. Table 1 shows the estimated daily calorie needs for older men and women.

In order to obtain all the nutrients needed for good health, older persons must select a diet rich in foods with high nutrient density—those with a high ratio of nutrients to calories. This becomes especially important in the later years of life when energy needs are quite low for many older persons.

Older adults who stay physically active are able to consume a higher calorie diet without gaining excess weight and have more flexibility in their food choices. Strength training can help older adults maintain or even increase their muscle mass and partially offset the natural decline in lean body mass and energy requirement that occurs with age. Educational programs that incorporate physical activity can help older persons increase their strength, flexibility, and energy level.

Credit: Thinkstock/Stockbyte

Water

Dehydration can be a significant problem for some older adults. During older age, the thirst mechanism is often compromised, so by the time an older person feels thirsty, he or she may already be dehydrated. In addition, the kidneys are often less able to concentrate urine in older adults, so the body loses more water. Some medications commonly taken by older persons have a diuretic effect, which further exacerbates issues with hydration. Dehydration can lead to headache, confusion, fatigue, and constipation.

Older adults should drink fluids on a regular basis, before they become thirsty. Some older persons limit fluid intake due to concerns about incontinence or having to use the bathroom during the night. Health professionals can encourage older adults to drink more fluids early in the day, and they should emphasize the importance of hydration to motivate older adults to drink enough fluid.

How much is needed?

Individual water needs vary based on body composition, activity level, state of health, and physical environment. As a general guide, the Institute of Medicine recommends that adults drink 9 cups (women) to 13 cups (men) of total fluids daily. Fluids include water, carbonated water (seltzer or club soda), fruit juices, milk, and other non-alcoholic beverages. Evidence confirms that habitual caffeine consumption has no effect on hydration status. Coffee, tea, and other caffeinated beverages do not need to be excluded (Institute of Medicine, 2006). If a person is under the care of a physician for congestive heart failure or another condition related to fluid balance, he or she may need to restrict their fluid intake. In this case, these general recommendations would not apply.

Protein

Adequate intake of dietary protein minimizes loss of skeletal muscle, helps older adults maintain strength and mobility, and decreases risk of falls. Individuals who are chronically ill, have suffered a trauma, or have an infection have a higher protein requirement. Foods high in protein include lean meat, poultry, seafood, milk, legumes, eggs, and nuts.

The current dietary recommendation for older adults and younger persons is the same (Institute of Medicine, 2006), but recent research indicates that older individuals may have a higher protein requirement (Nowson & O'Connell, 2015). Most Americans who eat enough food to meet their energy needs get an adequate amount of protein, but some older adults may have more difficulty getting the protein they need due to dietary restrictions or limited finances. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (Guidelines) recommend that we obtain protein from a combination of plant and animal sources, especially those low in solid fats. The most recent Guidelines recommend increasing the number of servings of fish/seafood and legumes to help meet the suggested amount of food from the protein food group while limiting saturated fat intake. Including a good protein source with every meal, including breakfast, may contribute to maintenance of muscle mass in older adults, although further study is needed before a recommendation can be made (Nowson & O'Connell, 2015).

What is the current recommendation?

19 years and older:

Men: 56 g/day*

Women: 46 g/day*

*These amounts were calculated for average weight adults (154 pounds for men and 126 pounds for women). Men and women who weigh more need more protein in their diets, which they can get by eating enough healthful, protein-rich foods. To calculate your protein needs, divide your body weight in pounds by 2.2 to get your body weight in kilograms. Multiply your weight in kilograms by 0.8 to get your dietary protein recommendation. As indicated above, the protein needs of older adults may be higher than the current recommendation. Older adults should speak with their health care provider about dietary protein intake and any other changes that will improve their nutritional status.

Fat

Fat provides taste and a pleasing texture to many foods. This is important for everyone who enjoys eating, but it can be especially important for older persons with a poor appetite. Fat adds energy density to foods, which may help those who have a poor appetite obtain adequate calories and stay well nourished.

On the other hand, consuming a diet high in fat, especially saturated fat, over a period of time increases risk of cardiovascular disease. Therefore, the amount of fat in the overall diet should be moderate. Older adults at risk for cardiovascular diseases should limit their intake of saturated fat and trans fat. Energy intake and disease risk reduction goals need to be determined based on each person's nutritional status and health risks.

Fiber

There are two categories of fiber: dietary fiber, which is found naturally in foods, and functional fiber, which is found in supplements and fiber-fortified foods. In addition, fiber can be classified as soluble or insoluble, both of which have health benefits. Most plant-based foods contain a mixture of soluble and insoluble dietary fiber.

Adequate intake of insoluble fiber from wheat bran, whole grains, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and seeds can reduce the risk of constipation, which is a common complaint among older persons.

The soluble fiber found in legumes, oat bran, barley, psyllium (found in some fiber supplements), and some fruits has been found to lower blood glucose and blood cholesterol in some people.

How much is needed?

The recommendation for daily fiber intake is based on energy requirements. Since the estimated energy requirement for older persons is lower than it is for young adults, the fiber recommendation is lower as well.

51 years and older:

Men: 30 g/day

Women: 21 g/day

Calcium and Vitamin D

These two nutrients work together to promote bone health. Older individuals, especially women, are at risk for osteoporosis, and adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D throughout life is one way to prevent excessive bone loss in the later years.

The recommended intakes of calcium and vitamin D increase with age, and many older adults do not get what they need from the food they consume. Older adults may limit their intake of dairy foods for a variety of reasons, including lactose intolerance, cultural preference, or personal taste.

Other sources of calcium include green leafy vegetables (NOT spinach due to high oxalate levels), tofu processed with calcium, and a variety of calcium-fortified foods, such as breakfast cereals and orange juice. Vitamin D is also found in some fortified foods, including milk, breakfast cereals, and orange juice. Check food labels to see if these nutrients were added to the food. For those who do not get adequate amounts of these nutrients from their diets, supplements are available to help them meet their nutrient needs.

Credit: ChristianJung/iStock/Thinkstock

How much is needed?

Calcium—Daily Needs

Men

51–70: 1,000 mg

Over 70 years: 1,200 mg

Women

51 years and older: 1,200 mg

Vitamin D—Daily Needs

Adults up to age 70: 15 mcg (600 IU*)

Over 70 years: 20 mcg (800 IU*)

*International Units

Fast Fact: Vitamin D is one of only a few nutrients for which there is an increase in recommended intake with age.

Putting It All Together

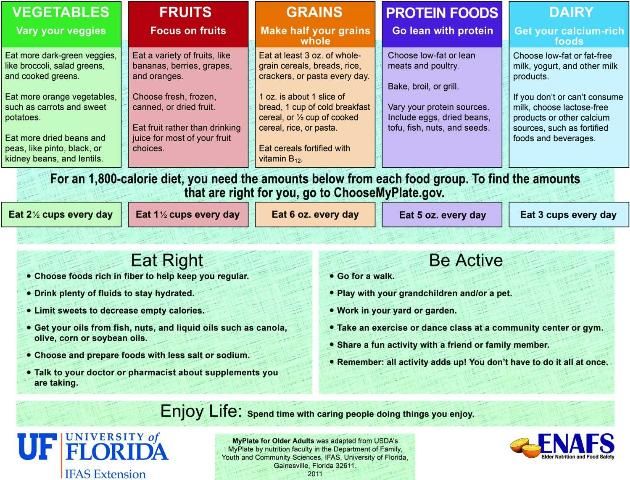

Since we select foods to eat rather than nutrients, the USDA has provided a food guide to help us make food choices that will meet our nutrient needs. Faculty at UF/IFAS incorporated USDA's MyPlate food guide into a two-sided mini-poster that highlights the special nutrient needs and lifestyles of older adults. The MyPlate for Older Adults mini-poster is presented in Figure 5 and is available at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy1260.

Credit: UF/IFAS

Credit: UF/IFAS

For More Information

Contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office for additional resources and educational programs. In Florida, you can find your local UF/IFAS Extension office at https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/find-your-local-office/.

Publications in This Series

Designing Educational Programs for Older Adults: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/fy631

Safe Return: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/fy626

Financial Issues: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/fy627

Elder Nutrition: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/fy628

Fall Prevention: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/fy629

Family Relationships in an Aging Society: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/fy625

Adapting the Home: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/fy630

The Future of Aging Is Florida: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy624

References

Bernstein, M. & Munoz, N. (2012). Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Food and nutrition for older adults—Promoting health and wellness. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 112(8): 1255–77.

Bobroff, Linda B. (2016). Healthy Eating: Improve Nutrition with SNAP. FCS8837. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00009206/00001

Eskelinen, K., Hartikainen, S., & Nykänen, I. (2016). Is loneliness associated with malnutrition in older people? International J. Gerontol. 10(1): 43–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijge.2015.09.001

Florida Department of Elder Affairs (FDEA). (2016). 2016 profile of older Floridians. Accessed on January 24, 2018. http://elderaffairs.state.fl.us/doea/pubs/stats/County_2016_projections/Counties/Florida.pdf

Institute of Medicine. (2006). Dietary Reference Intakes: The essential guide to nutrient requirements. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

Nowson, C. & O'Connell, S. (2015). Protein requirements and recommendations for older people: A review. Nutrients 7(8): 6874–99. Doi: 10.3390/nu7085311.

Strickhouser, S., Wright, J. D., and Donley, A. M. (2015). Food Insecurity Among Older Adults: Full Report, 2015 Update. Washington, D.C.: AARP Foundation.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2014). An aging nation: The older population in the United States—Population estimates and projections. U.S. Department of Commerce. Accessed on November 11, 2022. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p25-1140.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2015). Income and poverty in the United States: 2014—Current Population Reports. U.S. Department of Commerce. Accessed on January 24, 2018. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-252.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2017a). Income and poverty in the United States: 2016—Current Population Reports. U.S. Department of Commerce. Accessed on January 24, 2018. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2017/demo/P60-259.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2017b). The nation's older population is still growing, Census Bureau reports. U.S. Department of Commerce. Accessed on January 25, 2018. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/cb17-100.html

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living (ACL). (n.d.). 2016 profile. Profile of Older Americans. Accessed on January 24, 2018. https://acl.gov/aging-and-disability-in-america/data-and-research/profile-older-americans

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) & U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2015). Dietary Guidelines for Americans: 2015–2020. 8th edition. Accessed on November 11, 2022. https://health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/dietary-guidelines/previous-dietary-guidelines/2015