Aging in the 21st Century

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, by the year 2050 the nation's elderly population will more than double to 88 million, and the more frail, over-85 population will quadruple to 19 million.

Currently, Florida ranks first in the United States in the percent of the population who are full-time and seasonal residents over the age of 65. Older Floridians, their families, and communities face many issues related to aging.

Aging in the 21st Century is an eight-topic program that addresses issues such as:

- Health and medical care

- Family relationships

- Economic concerns

- Caregiving

- Home modifications

- Retirement

- Nutrition and diet

What You Will Learn

- Generation vs. Cohort: Definitions and differences between these two terms

- Family Structures: How the family structure is changing through the years

- Intergenerational Relations: What the major types of intergenerational relations are and support for the elderly within the family

Introduction

We will face many new issues as our society ages. Never in the history of America or the world has the population had more older adults than children.

This publication discusses some issues that happen as a result of having a greater number of older adults than children. It also looks at the roles of the family and intergenerational relationships supporting our aging society.

For example, how will the smaller workforce cope with providing for a larger retired community? What is the role of the family in caring for more than one generation of elders? How will modern families decide to distribute and share resources with aging parents and stepparents?

The Role of the Family

Most of us live our entire lives in the context of a family. Our family provides us with the important resources we need to help us learn independence as children and remain independent as older adults.

Throughout our lives we exchange help and support within the family. These exchanges can involve providing emotional and physical care, as well as financial support.

The family becomes more and more important for the elderly as the need for support increases. Yet we must remember that the aging person and the family are all part of a larger society. Society impacts the resources and services available to older adults and their families.

Two terms, generation and cohort, are frequently used when discussing aging. These terms help explain family and societal aspects of aging.

We use the term generation to better understand the impact of aging on the family. A generation is a group of people at the same step in the line of the family. In a family, children, parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents reflect different generations.

People in the same generation often have common roles, responsibilities, and expectations. For example, those in the "parent generation" are responsible for raising their children, caring for their parents and/or grandparents, and taking care of their own personal responsibilities. This is why they have been called the "sandwich generation." Family members from different generations often have different ideas about life in the family and what it should be like.

We use the term cohort when we are talking about society instead of the family. A cohort defines a group of people who were born during the same time in history.

People in the same cohort were born around the same time, which means they have lived through time and history together. They may share common experiences and often common beliefs. For example, the "baby boomers" (born between 1946 and 1964) are a cohort. They experienced the years of the "traditional family" (e.g., mom, dad, and children), and the Vietnam era. The cohort born in the early part of the 19th century shared two World Wars as well as the Great Depression.

Having these common experiences molds a cohort's expectations of aging. Clashes between cohorts occur when people from different cohorts fail to recognize the differences in their experiences.

Changes in the Structure of the Family

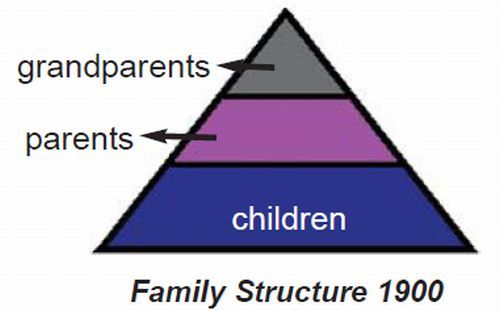

In the 1900s, families in the United States commonly had many children. Also, grandparents usually died before their grandchildren reached adulthood. This meant the family structure looked like a pyramid with a large number of children and parents and very few grandparents.

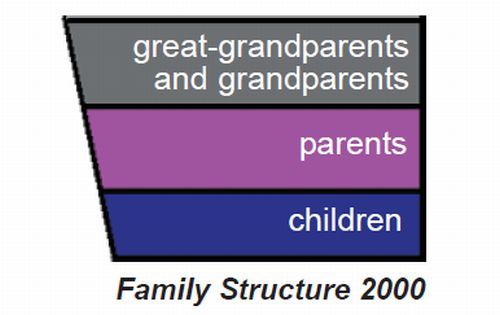

In the 2000s, however, the family model is more like a lopsided rectangle. More generations are alive at the same point in time than in past eras. Families have fewer children, but grandparents and great-grandparents are living longer.

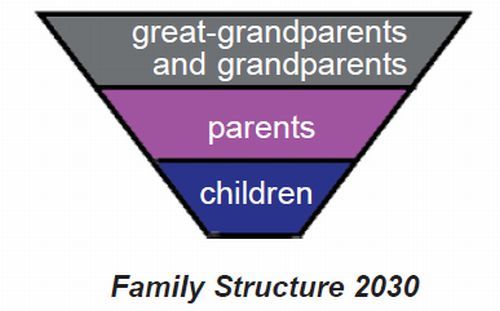

By 2030 the boomers will be grandparents and great-grandparents. This means the top of the pyramid will be quite broad, and there will be fewer parents and children.

Understanding the impact of these changes is important for families and society. More members in the older generation may help families raise children. But older members may require care and support. Policy makers must consider these changes as they plan for schools and health care.

Intergenerational Relations

We have all seen the ideal image of the family often portrayed by the media. On television, family members rarely argue. And, when they do, the problems are solved before the program ends. In real life, family members often disagree. Sometimes they may decide to leave the family entirely. Frequently, the disagreements are between people from different generations.

Relationships between children and their parents, parents and grandparents, or children and their grandparents are called intergenerational relationships.

Generations interact differently in different families. Some are emotionally close, while others are emotionally distant. Some families spend a great deal of time together, while others rarely see one another.

Researchers look at three dimensions of intergenerational interactions to better understand families: 1) emotional closeness, 2) frequency of contact, and 3) social support.

Using these three dimensions we see five types of intergenerational relations in families:

- Tight-Knit: Families are emotionally close and have frequent contact with one another. If they live close together, they see each other often. If they live farther apart, they remain close emotionally with frequent phone calls, emails, or letters. These families take care of one another across generations.

- Sociable: Families are emotionally close across generations and have frequent contact with one another. They are less likely to provide care for one another.

- Intimate: Families describe themselves as emotionally close but don't visit frequently and may live far away from one another. They rely on others to provide care for family members.

- Obligatory: Families see one another frequently and provide support across generations. These families don't feel especially close emotionally but provide care and support if necessary.

- Detached: Families are not close emotionally, don't see one another often, and do not provide support or care for one another.

Did you know?

- Adult children are more likely to have a tight-knit relationship with their mothers than their fathers.

- Adult children are also more likely to have a detached relationship with divorced parents.

Social Support

Older people often rely on family members for help. They may need help with the demands of everyday life because of a chronic illness or during a crisis. Adult children may have a strong sense of responsibility and commitment toward their aging parents. Many adult children provide caregiving in spite of time, distance, or competing responsibilities. The help provided to older adults is called social support. Family members provide four basic types of social support:

- Instrumental: Housework, transportation, shopping and personal care.

- Emotional: Confiding, comforting, reassuring, and listening to problems.

- Informational: Advice in seeking medical treatment, referrals to agencies, sharing family news.

- Financial and Housing: Help paying bills, sharing a home.

We know that families provide most of the help for frail and disabled elderly who live in the community. Family members and the elderly often prefer it that way.

There are two ways of understanding how older adults get help:

- Principle of Substitution

- Task-Specific Model

The Principle of Substitution describes the order in which older adults choose their care providers. Married older adults prefer to receive help from their spouses. If a spouse is not available or unable to help, they turn next to their children and other relatives. Friends and neighbors help by driving, picking up groceries and medicines, and checking on the older person. Older adults turn to professionals as a last resort.

The Task-Specific Model states that different tasks require the help of different people. For example, spouses and close family members provide the kind of help that requires a great deal of time and energy. They also perform personal tasks such as bathing. Friends and neighbors help with errands, provide transportation, and offer leisure activities. Professionals are called only when the tasks of social support become too time-consuming, too technical, or too difficult.

If the time comes when continued professional help is needed, the family may have to consider institutionalization, such as a nursing home. That choice is only made when the people identified in the Principle of Substitution are no longer able to continue managing in-home care.

For more information on Aging in the 21st Century please refer to the following publications and/or contact your local Extension office.

Publications in This Series

- Designing Educational Programs for Older Adults (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy631), Martie Gillen, PhD, Carolyn Wilken, PhD, MPH, and Jenny Jump, M.S.

- Safe Return (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy626), Martie Gillen, PhD, and Meredeth Rowe, RN, PhD

- Financial Issues (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy627), Martie Gillen, PhD, and Jo Turner, PhD, CFP

- Elder Nutrition (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy628), Linda Bobroff, PhD, RD, LD/N

- Fall Prevention (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy629), Martie Gillen, PhD, Kristen Smith, MPH, and Jenny Jump, M.S.

- Family Relationships in an Aging Society (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy625), Martie Gillen, PhD, Terry Mills, PhD, and Jenny Jump, M.S.

- Adapting the Home (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy630), Martie Gillen, PhD, Pat Dasler, MA, OTR/L, and Jenny Jump, M.S.

- The Future of Aging Is Florida (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fy624), Martie Gillen, PhD, and Jeffrey Dwyer, PhD

Aging in the 21st Century is co-sponsored by the University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS), Department of Family, Youth and Community Sciences, and the College of Medicine's Institute on Aging. It was originally published in 2003 and was supported by a grant from the Associate Provost for Distance, Continuing and Executive Education, Dr. William Riffee.

Reference

US Census Bureau. 2010. "The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050." Accessed February 2022. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2010/demo/p25-1138.pdf