Introduction

Spring viremia of carp virus (SVCv) is the cause of a viral disease that can lead to significant mortality in several cyprinid species and the wels catfish (Silurus glanis). Some of these species are raised as a foodfish in many countries and koi carp have been selectively bred for the ornamental fish industry. Historically, the disease has been a problem in Europe, the Middle East, and Russia, but was reported in koi and feral carp in the United States for the first time in 2002. Listed as a notifiable disease by the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH 2025) and USDA National Animal Health Reporting System National List Of Reportable Animal Diseases (NAHRS NLRAD) (https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/surveillance/reportable-diseases) diagnosis of SVC in the US, in wild and farmed populations, is reportable to USDA. This information sheet is intended to inform veterinarians, biologists, culturists, and hobbyists about SVCv.

What Is Spring Viremia of Carp?

Spring viremia of carp is an infection caused by Rhabdovirus carpio (also known as Carp sprivivirus), a bullet-shaped RNA virus. Natural infections with the virus have been reported in common carp (or koi) (Cyprinus carpio), goldfish (Carassius auratus), grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), zebrafish (Danio rerio), golden shiner (Notemigonus crysoleucas), and fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas), as well as other species not common in the US (see WOAH Manual of Diagnostic Tests for Aquatic Animals, Chapter 2.3.9; https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/).

Where Is It Found?

Thought to be present in Europe for decades, spring viremia of carp virus (SVCv) was initially diagnosed in Yugoslavia (Fijan et al. 1971). Since then, it has been identified in other European countries, Russia, Brazil, the Middle East, China, and North America.

In the US, SVCv has been diagnosed both in farmed koi and feral common carp. In 2002, it was confirmed in farmed koi from North Carolina and in feral carp in Wisconsin. It is important to note there was no connection between the two cases. It was also diagnosed in pet koi in Washington and farmed koi Missouri in 2004 and in feral common carp in the Mississippi River in Minnesota in 2007. The most recent SVCV finding was in 2011 in feral carp in Minnesota waters. SVCV is not believed to be widespread in the US but rather limited to certain areas in wild susceptible populations. For purposes of disease regulation, USDA considers spring viremia of carp virus a foreign animal disease in the United States.

What Are the Signs of SVC Disease?

Clinical signs of infection with SVCv are often non-specific. Affected fish may appear lethargic, exhibit decreased respiration rate and loss of equilibrium. Moribund fish have been reported to lie on their sides, often on the bottom of the tank, and when startled swim up but then return to the bottom. Fish are also reported to congregate where there is slow water flow and near pond banks (Fijan 1999).

Other clinical signs may include darkening of the skin; exophthalmia (pop-eye); coelomic distension (dropsy); pale gills; hemorrhages in the gills, skin, and eye; and a protruding vent with a thick mucoid (white to yellowish) fecal cast (see Figure 1).

Credit: Andy Goodwin

Internally, edema (fluid buildup in organs and in the body cavity) and inflammation in many organs may be present. Pinpoint hemorrhages are often observed in the wall of the gas bladder and other internal organs. The intestine may be severely inflamed and may contain significant amounts of mucus. The spleen is often enlarged.

Concurrent infection with bacteria, particularly Aeromonas (A. salmonicida or A. hydrophila), may confuse the diagnosis because fish with this bacterial disease alone will show similar signs of systemic infection such as ascites and hemorrhages.

Transmission of SVCv

The rhabdovirus that causes SVC disease enters the fish through the gills, replicating in gill epithelium and spreading to internal organs (Ahne 1978; Baudouy et al. 1980). The virus is transmitted to other susceptible fish via exposure to infected animals and contaminated water. Blood-sucking parasites, including leeches and the fish louse Argulus, have been implicated in spreading the disease (Pfeil-Putzien 1977; Ahne 1985). Mechanical transmission by aquatic animals, birds, and equipment is suspected because of the longevity of the virus in water and mud and following desiccation (Ahne 1982a; Ahne 1982b). The virus can survive freezing for one month at -20°C (-4°F); thus, frozen infected fish that are fed to piscivorous fishes or other animals may spread the virus to other locations (WOAH 2015a).

The presence of virus in ovarian fluids suggests that vertical transmission (from female parent to offspring) may be possible (Bekesi and Csontos 1985), but there is no evidence this has occurred.

Fish that survive an outbreak of SVCv may develop immunity to the virus. However, long-term sub-clinically infected fish may shed virus and thus serve as a source of virus to unexposed fish. Fish exposed to virus should be considered to be carriers. The length of time carrier fish can shed virus is unknown.

Credit: Andy Goodwin

Factors That Influence Disease

Young fish are more susceptible to infection with SVCv; mortality can reach 70% in yearling carp (Plumb 1999; OIE 2015a). Adult fish can also be affected, but usually to a lesser degree.

Although other factors, such as age, can determine how severely the disease will affect a population, the temperature at which fish become infected, temperature fluctuations during the infective period, and the ability of the fish to mount a timely immune response seem to be the most important components for SVCV.

In disease outbreaks, mortalities generally occur between 11°C and 17°C, and rarely below 10°C. As temperatures exceed 22°C, mortalities, especially in older fish, decline (Fijan 1988). Bacterial or parasitic co-infections may affect when clinical signs are observed as well as mortality rates. Other stressors, such as transport, may initiate disease.

Fish that are exposed to physiological stressors such as crowding, handling, poor water quality, malnutrition, and sudden temperature changes are more susceptible because of resulting immune system suppression.

How Is SVCv Diagnosed?

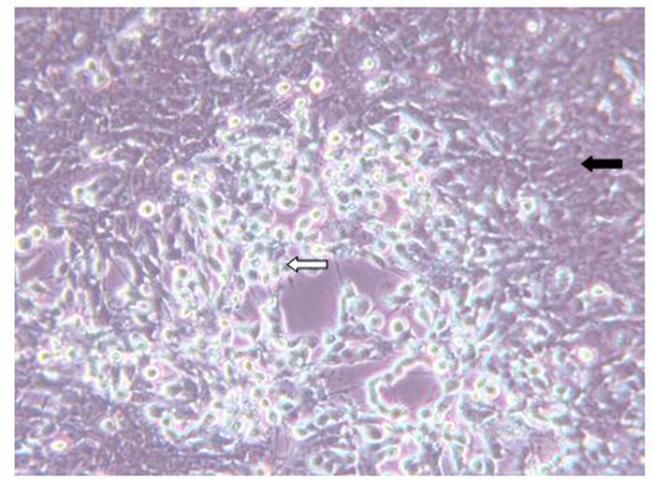

Diagnosis of SVCv can be accomplished by several methods. A direct method is to isolate the virus using fathead minnow (FHM) or epithelioma papillosum of carp (EPC) cell lines. If a virus is present to which the cells are susceptible, it will cause the cells to degenerate and round (see Figure 2). To identify the viral agent, additional tests, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), must be performed. A diagnostic manual that includes protocols required to confirm a diagnosis of SVC is available online and in print (WOAH Aquatic Manual, Spring Viremia of Carp Virus, chapter 2.3.9, https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/).

Suspect cases of SVC in the US can be sent to any lab that can test for the disease; however, samples collected for the purpose of meeting export requirements must be sent to a USDA-approved lab https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/approved-labs-aquaculture.pdf.

If a sample tests positive for the virus, the detection should be reported to USDA by contacting the Area Veterinarian in Charge (AVIC) in the state where animals are located (https://www.aphis.usda.gov/contact/animal-health). Confirmation testing is completed at the USDA National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL) in Ames, Iowa—https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/lab_info_services/downloads/ContactByDisease.pdf.

How Are SVC Outbreaks Managed?

Antiviral drugs are not available to treat SVCV or other viral diseases of cultured fish. Due to the potential severity of the disease and regulatory concerns, depopulation is recommended. Additionally, there is no vaccine to protect against SVCv infection.

In active outbreaks, efforts are directed at containing and/or quarantining infected and exposed stock and disinfecting all areas where infected fish were held. However, in some circumstances, this may be difficult. The virus can be infective in mud and water for up to 42 days (Plumb 1999). It can also survive in water without a host for 5 weeks at 10°C (50°F) (WOAH ).

Though the virus is hardy, it can be inactivated by a number of methods. Appendix A lists chemical concentrations and application times to achieve inactivation of the virus. All equipment and tanks, raceways, and ponds should be disinfected. Ponds that have housed infected fish should be fallowed (left unstocked) for a period of time. Restocking with non-susceptible species or sentinel, young fish from SVC-free farms is recommended.

How Can SVCv Infections Be Prevented?

Biosecurity measures should be followed, especially when working with SVCv-susceptible fish species. These measures should include:

- New fish should be purchased from SVC-free suppliers and farms.

- If surface water is used to supply the farm, it should first be disinfected against SVCv. Well water is considered to be a safe source of water.

- Maintain a dedicated set of equipment for SVC-susceptible species and disinfect it between ponds or tanks.

- Animals such as birds, livestock, pets, etc., should be restricted from access to ponds or tanks.

- Restrict visitors. Only farm personnel should have access to ponds or tanks, and they should be trained in biosecurity measures.

- Because many farms culture multiple fish species, it is highly recommended that SVCv-susceptible species be kept separate from non-susceptible species.

- Perform routine health assessments including SVCv testing on susceptible populations.

Regulatory Considerations

Spring viremia of carp virus is listed as a notifiable disease by the WOAH in the Aquatic Animal Health Code (WOAH 2025). It is also a notifiable disease in the United States. See https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/surveillance/reportable-diseases.

As a listed pathogen, suspect or laboratory detections of SVCV should be reported to USDA APHIS Veterinary Services. It is also on Florida's list of reportable diseases (https://www.fdacs.gov/Consumer-Resources/Animals/Animal-Diseases/Reportable-Animal-Diseases). Appendix B lists websites for locating state and federal officials. If SVCv is diagnosed, a state may choose to quarantine the infected facility to prevent movement of infected animals.

For farms that wish to attain SVC-free status, a USDA-accredited veterinarian should be contacted to provide guidance on how to accomplish this status. Criteria for establishing a farm or population as SVCv-free may vary depending on the reason for testing, for example, international export or interstate movement. A common requirement is to collect at least 175 susceptible fish that are one year old or less for SVCv testing twice a year when water temperatures are within the optimal range for SVCv detection. Specific biosecurity measures may also be required. If a farm meets those biosecurity standards and obtains two years of negative SVCV results, a farm may be considered SVCV-free. However, to retain that status, the farm must continue to have annual SVCV testing. Criteria for SVCV-free status for aquaculture facilities and geographic regions are listed in the WOAH Aquatic Animal Health Code (WOAH 2025).

Importation of Spring viremia of carp virus-susceptible species and their eggs and gametes require a USDA import permit (form VS-135) and health certificate issued from the country of origin. A USDA guide sheet for live finfish imports can be found at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/animal-and-animal-product-import-information/live-animal-imports/aquatic-animals/fish-eggs-gametes.

References

Ahne, W. 1978. "Uptake and multiplication of spring viremia of carp virus in carp, Cyprinus carpio L." Journal of Fish Diseases 1:265–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2761.1978.tb00029.x

Ahne, W. 1982a. "Vergleichende untersuchungen über die stabilität von vier fischpathogenen viren (VHSV, PFR, SVCV, IPNV)." Zentralblatt für Veterinärmedizin (B)29:457–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.1982.tb01248.x

Ahne, W. 1982b. "Untersuchungen zur tenazität der fischviren." Fortschritte in der Veterinärmedizin 35:305–309.

Ahne, W. 1985. "Argulus foliaceus L. and Philometra geometra L. as mechanical vectors of spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV)." Journal of Fish Diseases 8:241–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2761.1985.tb01220.x

Baudouy, A.M., Danton, M. and Merle, G. 1980. "Virémie printanière de la carpe: résultants de contaminations expérimentales effectuées au printemps." Annales de Recherches Veterinaires 11:245–249.

Bekesi, L. and Csontos, L. 1985. Isolation of spring viraemia of carp virus from asymptomatic broodstock carp, Cyprinus carpio L. J. Fish Dis., 8:471–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2761.1985.tb01281.x

Brown, L.L. and Bruno, D.W. 2002. "Infectious diseases of coldwater fish in fresh water." In: Woo, P.T.K, Bruno, D.W, and Lim, L.H.S. (eds.), Diseases and Disorders of Finfish in Cage Culture. CABI Publishing: Oxon, UK, PP. 116–118. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851994437.0107

Emmenegger, E.J. and Kurath, G. 2008. "DNA vaccine protects ornamental koi (Cyprinus carpio koi) against North American spring viremia of carp virus." Vaccine 26:6415–6421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.08.071

Fijan, N. 1972. "Infectious dropsy in carp: a disease complex." Symposium of the Zoological Society of London 30:39–51.

Fijan N. 1988. Vaccination against spring viraemia of carp. In: Ellis, A.E. (ed.), Fish Vaccination. Academic Press, London, UK, 204–215.

Fijan, N. 1999. "Spring viremia of carp and other diseases and agents of warm-water fish." In: Woo, P.T.K. and Bruno, D.W. (eds.), Fish Diseases and Disorders, Volume 3, Viral, Bacterial and Fungal Infections. CABI Publishing: Oxon, UK, pp 177–244.

Fijan, N., Petrinec, Z., Sulimanovic, D., Zwillenberg, L. 1971. "Isolation of the viral causative agent from the acute form of infectious dropsy of carp." Veterinarski Arhiv 41:125–138.

Hill, B. 1977. "Studies of spring viremia of carp virulence and immunization." Bulletin de L'Office International des Épizooties 87:455–456.

McAllister, P.E. 1993. "Goldfish, koi, and carp viruses." In: Stoskopf, M.K. (ed). Fish Medicine. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, PA, pp 478–486.

Macura, B., Tesarcik, J., and Rehulka, J. 1983. "Survey of methods of specific immunoprophylaxis of carp spring viremia in Czechoslovakia." Práce VÚRH (Výzkumný ústav rybářský a hydrobiologický ) Vodňany (English = Papers of RIFH [Research Institute of Fishery and Hydrobiology] Vodnany) 12:5056.

Pfeil-Putzien, C. 1977. "New results in the diagnosis of spring viremia of carp caused by experimental transmission of Rhabdovirus carpio with carp louse (Argulus foliaceus)." Bulletin de L'Office International des Épizooties 87:457.

Plumb, J.A. 1999. Health Maintenance and Principal Microbial Diseases of Cultured Fish. Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA, pp 77–90.

Smail, D.M. and Munro, L.S. 1989. "The virology of teleosts." In: Roberts, R.J. (ed), Fish Pathology, second edition. Balliere-Tindall, London, UK, pp 173–241.

World Organisation for Animal Health. 2025. WOAH Aquatic Animal Health Code. https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/

World Organisation for Animal Health. 2025. WOAH Manual of Diagnostic Tests for Aquatic Animals. https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/

Wolf, K. 1988. Fish Viruses and Fish Viral Diseases. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, pp 191–216.

Recommended Reading

APHIS Veterinary Services. 2024. Spring viremia of carp virus. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/aquaculture/spring-viremia-carp

The Center for Food Security & Public Health. 2007. Spring viremia of carp. https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/spring_viremia_of_carp.pdf

US Fish & Wildlife Service News Release. 2007. Carp virus discovered in upper Mississippi River. https://www.fws.gov/story/2007-06/carp-virus-discovered-upper-mississippi-river

Appendix A

Methods to inactivate SVCv (Smail and Munro 1989; Fijan 1999; WOAH 2025)

- 3% formalin for 5 minutes

- oxidizing agents

- ozone

- Virkon® Aquatic

- detergents

- sodium dodecyl sulfate

- non-ionic detergents

- sodium hypochlorite (chlorine at 540 ppm for 20 minutes)

- organic iodophors (200–250 ppm) for 30 minutes

- benzalkonium chloride (100 ppm for 20 minutes)

- alkyltoluene (350 ppm for 20 minutes)

- chlorhexidine gluconate (100 ppm) for 20 minutes

- sodium hydroxide for 10 minutes

- gamma and ultraviolet irradiation

- extreme pH (pH 3 for 3 hours or pH 12 for 10 minutes)

- heating at 60°C (140°F) for 30 minutes

Appendix B

USDA APHIS Area Veterinarians in Charge (AVIC) https://www.aphis.usda.gov/contact/animal-health.

Acknowledgement

To Dr. Andy Goodwin of the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff for graciously sharing his photos.