The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The family Platypodidae includes over 1,000 species, most of which are found in the tropics (Schedl 1972). Seven species of platypodids, all in the genus Platypus, are found in the United States, four of which occur in Florida. All species found in Florida are borers of trunks and large branches of recently killed trees and may cause economic damage to unmilled logs or standing dead timber. The most recent key to species was published more than 80 years ago (Chamberlin 1939), does not include all species known from the United States (Wood 1979), and has long been out of print.

Identification

The Platypodidae are closely related to the Scolytidae, but can be distinguished by the elongate body form, short abdomen (shorter than metathorax in lateral view), and elongate first tarsal segment, which is longer than the remaining segments combined.

Credit: David T. Almquist, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

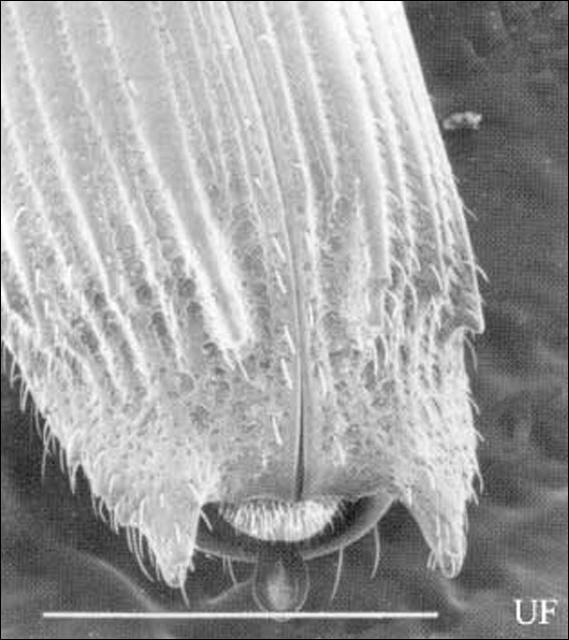

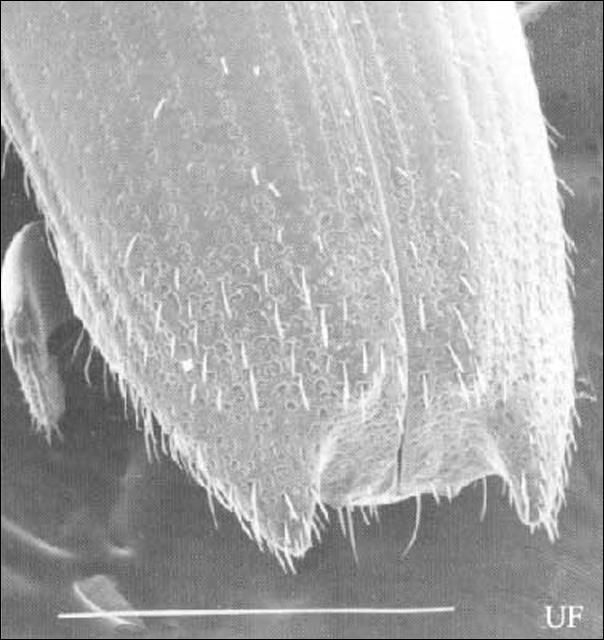

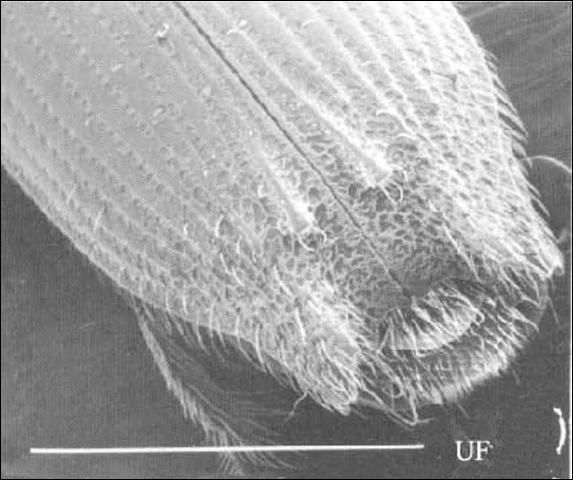

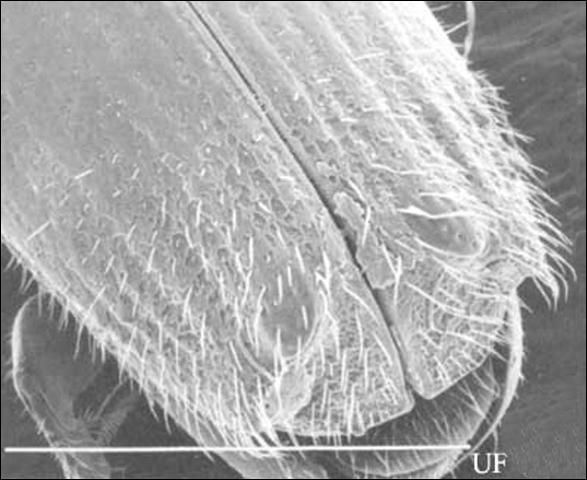

Males of all species have more developed armature (spineous or chitinous processes) of the elytral declivity (sloping area) than females.

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Females of species occurring in Florida lack terminal spines on the elytra except for Platypus flavicornis (Fabricius), which has blunt projections. Females of all species have larger maxillary palpi and a larger gular region than males. (See figures displaying ventral view of heads.)

The following key and accompanying illustrations will allow identification of both sexes of all species occurring in Florida and the eastern United States.

Key to Species of Platypus of Florida

1. Male declivity with large acuminate process arising from interstria 9 on posterolateral margins of elytra; interstria 3 continuing posteriorly as a spinose process, interstria 1 not elevated (Figures 8, 14); female declivity with blunt projection at apex of interstria 3 or at apex of interstria 9, apical margin of declivity straight, not explanate (spread out and flattened) (Figures 9, 15) . . . 2

1' Male declivity with large blunt process arising from interstria 9 on posterolateral margins of elytra ending in three terminal spines; interstria 1 continuing posteriorly as a spinose process, interstria 3 not elevated or conspicuously less so than 1 (Figures 10, 12); female declivity blunt, without projecting apical tubercles or processes, apical margin of declivity shallowly divaricate (forked) at suture, slightly explanate (Figures 11, 13) . . . 3

2 (1). Male declivity with prominent spines on venter of third visible abdominal segment, posterolateral processes of declivity laterally compressed (Figure 14); female declivity without apical projection of posterolatreal area of elytra (Figure 15); female pronotum with pair of large conspicuous pores in middle (Figure 7). Southeastern U.S. In oaks . . . quadridentatus (Olivier)

2' Male declivity without spines on venter of abdomen; posterolateral processes of declivity acute, not compressed (Figure 8); female declivity with blunt posterolateral projections on elytra, less acute than those of male (Figure 9); female pronotum without conspicuous pores. Southeastern U.S. In pines . . . flavicornis (Fabricius)

3 (1). Pronotum of both sexes with a pair of tiny pores in middle (Figure 6); male elytral stride shallowly impressed, interstriae 3 times as wide as striae at base of declivity (Figure 10). Southeastern U.S. Neotropics . . . compositus (Say)

3' Pronotum without conspicuous pores in either sex; male elytral striae deeply impressed, subequal in width to interstriae at base of declivity (Figure 12). Southern Florida. Circumtropical . . . parallellus (Fabricius)

Biology

All species are ambrosia beetles and generally breed in large diameter host material. Galleries are initiated by males; each male is joined by a single female. Pheromones are produced and large numbers of simultaneous attacks are frequently observed. Mated pairs tunnel into the heartwood and introduce ectosymbiotic fungi into their tunnels upon which they and their brood feed. For the most part the wood is not actually consumed. Larvae move freely inside the parental tunnels and excavate individual pupal cells off the main tunnels. Adults emerge through the original entry hole. Platypodids can only breed in undegraded, recently killed host material, with a high moisture content. Decaying wood or wood which has dried out is unsuitable. Normally, only a single generation can be produced in a given host. Platypus flavicornis and Platypus quadridentatus are respectively restricted to pines and oaks. Platypus compositus and Platypus parallelus are extremely polyphagous and will breed in most trees within their ranges. These latter two species are commonly attracted to light.

Distribution

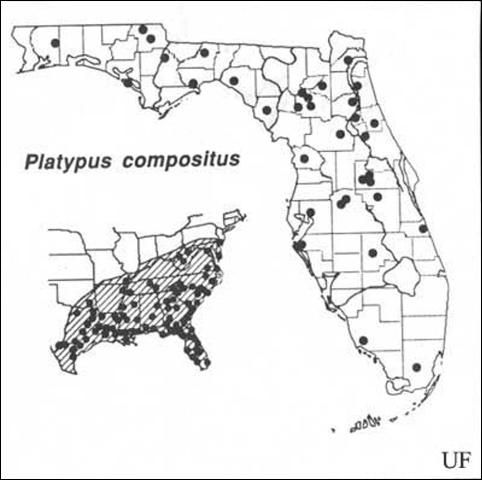

See Figures 16, 17, 18 and 19.

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Credit: T. H. Atkinson, UF/IFAS

Damage

Credit: Ronald F. Billings, Texas Forest Service, www.forestryimages.org

Credit: Ronald F. Billings, Texas Forest Service, www.forestryimages.org

Selected References

Beal, J.A., and C.L. Massey. 1945. Bark beetles and ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Scolytoidea) with special reference to the species occurring in North Carolina. Duke Univ. Sch. Forestry Bull. No. 10. 178 pp.

Blackman, M.W. 1922. Mississippi bark beetles. Miss. Agric. Exp. Sta. Tech. Bull. 11: 1–130.

Chamberlin, W.J. 1939. The bark and timber beetles of North America north of Mexico. Oregon St. Univ., Corvallis. 513 pp.

Schedl, K.E. 1972a. Monographie der Famile Platypodidae (Coleoptera). W. Junk, The Hague. 322 pp.

Staines, C.L. 1982. Distributional records of Platypodidae (Coleoptera) in Maryland. Proc. Ent. Soc. Wash. 84: 858–859.

Wood, S.L. 1958. Some virtually unknown North American Platypodidae (Coleoptera). Great Basin Natur. 18: 37–40.

Wood, S.L. 1979. Family Platypodidae. A Catalog of the Coleoptera of America north of Mexico, fasc. 141. U.S. Dept. Agric. Agric. Handbook 529-141.