Background

The purpose of this publication is to (i) document trends in total acres of rice planted in the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA), Florida, between 2008 and 2021; and (ii) determine the percent acreage of the varieties that are being grown. Local growers, regulators, and researchers would particularly benefit from such information because it provides them with the acreage for each rice variety produced in the EAA and the benefits of cultivating it as a rotation crop with sugarcane. This type of information is also useful in the variety selection process while planning for the following year.

Rice production in the Everglades Agriculture Area (EAA) of Florida dates back nearly seven decades. For a brief period of time during the 1950s, about 2,000 ac of rice were grown in the EAA. Although the rice industry produced satisfactory yields, the discovery of the rice ‘hoja blanca’ (white leaf) virus, which was reported first in the late 1950s in Columbia and Venezuela, led to a federal quarantine of rice production in the state of Florida.

Rice was reintroduced in the EAA in 1977 after it was demonstrated that rice could be successfully incorporated into the sugarcane production cycle during the fallow period (Alvarez et al. 1978). The EAA comprises 445,000 ac of Histosols devoted primarily to sugarcane production. During the summer period, more than 50,000 ac of fallow sugarcane land are available for rice production. This is because South Florida is too hot in the summertime to grow specialty crops, such as leafy vegetables or sweet corn. In 2021, approximately 23,000 ac of rice were planted in the EAA (Florida Rice Growers Inc., 2022). The net value of growing rice in the EAA as a rotation crop far exceeds its monetary return. In addition to being a food crop in Florida, production of flooded rice provides several benefits to the agroecosystem. By flooding fields, growers greatly reduce the negative impacts from issues related to soil subsidence (Bhadha et al. 2020), improve soil health (Bhadha et al. 2018), reduce nutrient depletion, and reduce damage from insect pests (Cherry et al. 2015). This, in turn, enhances the subsequent sugarcane crop and maximizes the longevity of the soil by reducing soil loss due to oxidation. In addition, incorporating rice as a rotation crop in the EAA during the summer months also provides local employment (Schueneman et al. 2008). In 2021, eleven commercial varieties of rice were planted in the EAA (Diamond, LaKast, Cheniere, Rex, Mermentau, Titan, Jewel, Mix, and three Hybrid varieties) and evaluated on a yield-per-acre basis. Approximately 974,525 hundredweight (cwt; 1 cwt = 100 lb) of whole rice (broken, sub-products, and ratoon rice not included) was produced in 2021.

Rice Production in the EAA—2008 to 2021

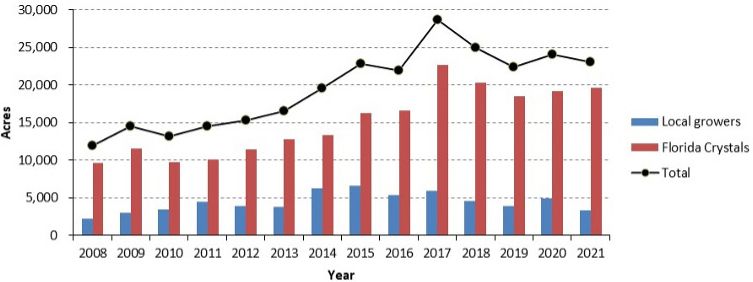

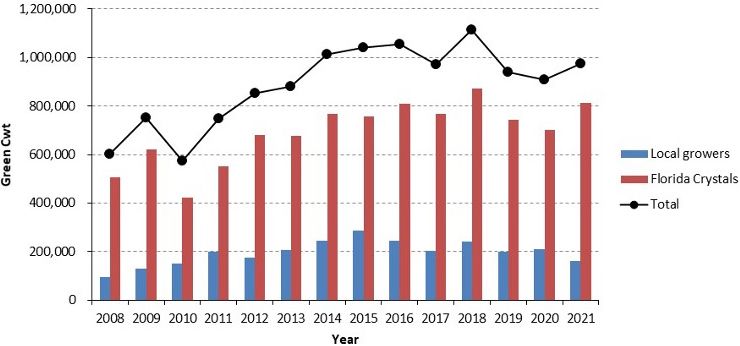

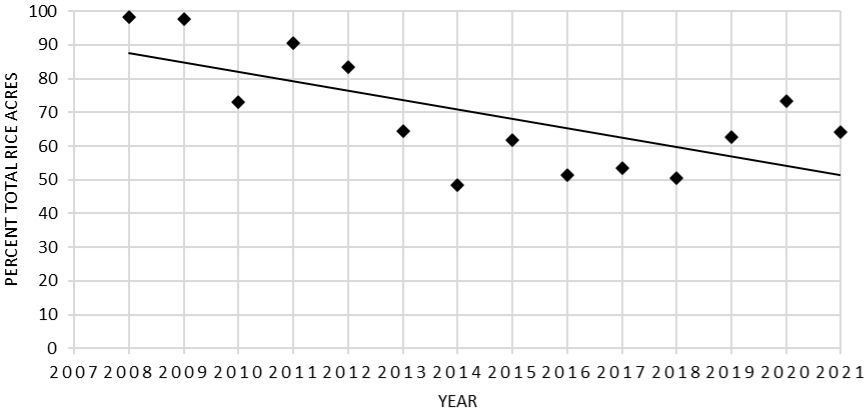

Rice production in the EAA has been steadily increasing since 2008 at a rate of ~1,081 ac yr-1 (Figure 1). Florida Crystals Corporation (FCC) is the largest rice producer in the EAA, while the remaining rice is produced by local growers. The local growers are made up of farmers who grow sugarcane and winter vegetables, rotating with rice in the summer. They are part of the Sugar Cane Growers Cooperative of Florida and individually own >3,000 ac of land per farm. In 2008, a total of 11,912 ac of rice was planted in the EAA, of which 9,644 ac were planted by FCC and 2,268 ac were planted by local growers. In 2015, a total of 22,861 ac of rice was planted in the EAA, of which 16,297 ac were planted by FCC and 6,564 ac were planted by the local growers. In 2018, a total of 24,986 ac of rice was planted in the EAA, of which 20,365 ac were planted by FCC and 4,621 ac were planted by local growers. In 2021, a total of 23,058 ac of rice was planted in the EAA, of which 19,662 ac were planted by FCC and 3,396 ac were planted by local growers. The amount of rice harvested is reflective of the acreage planted. In 2008, 602,320 cwt of green rice was harvested compared to 1,042,000 cwt in 2015; 1,112,658 cwt in 2018; and 974,525 cwt in 2021 (Figure 2). Between 2008 and 2021, rice yields in the EAA had averaged 46.56 cwt ac-1. The highest average yields were observed in 2012 at 56.0 cwt ac-1, while the lowest was observed in 2017 at 33.90 cwt ac-1. The low yields of 2017 were a result of Hurricane Irma, which damaged a significant acreage of rice stands, rendering them un-harvestable.

Credit: Dr. Jehangir Bhadha, UF/IFAS; Luigi Trotta, King Ranch Inc.; Daniel Cavazos, Florida Crystals Corporation; and Dr. Matthew VanWeelden, UF/IFAS

Credit: Dr. Jehangir H. Bhadha, UF/IFAS; Luigi Trotta, King Ranch Inc.; Daniel Cavazos, Florida Crystals Corporation; and Dr. Matthew VanWeelden, UF/IFAS

Rice Varieties Grown in the EAA

Rice is produced on a smaller scale in south Florida than in other states such as Arkansas, California, Louisiana, and Texas, limiting the amount of resources available to the growers. While research and Extension personnel are available to address the needs of rice growers, historically the industry has suffered from a lack of diversity in terms of available varieties. Because neither UF/IFAS nor USDA-ARS have dedicated rice breeders, Florida is dependent on using varieties acquired from breeding programs in other states. More importantly, this lack of diversity in Florida rice leaves the industry susceptible to disease and insect pest outbreaks.

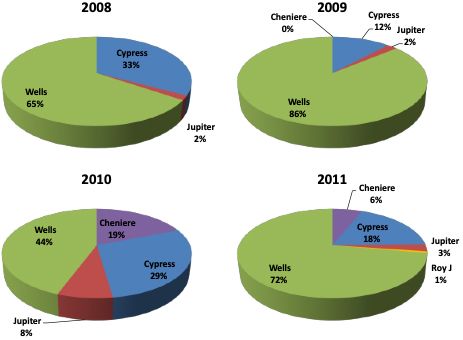

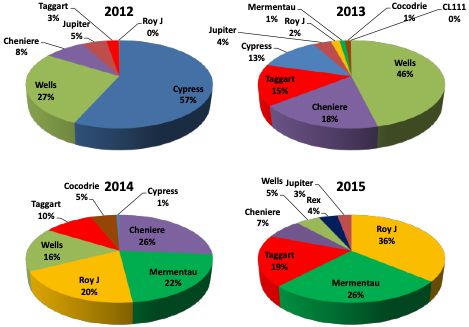

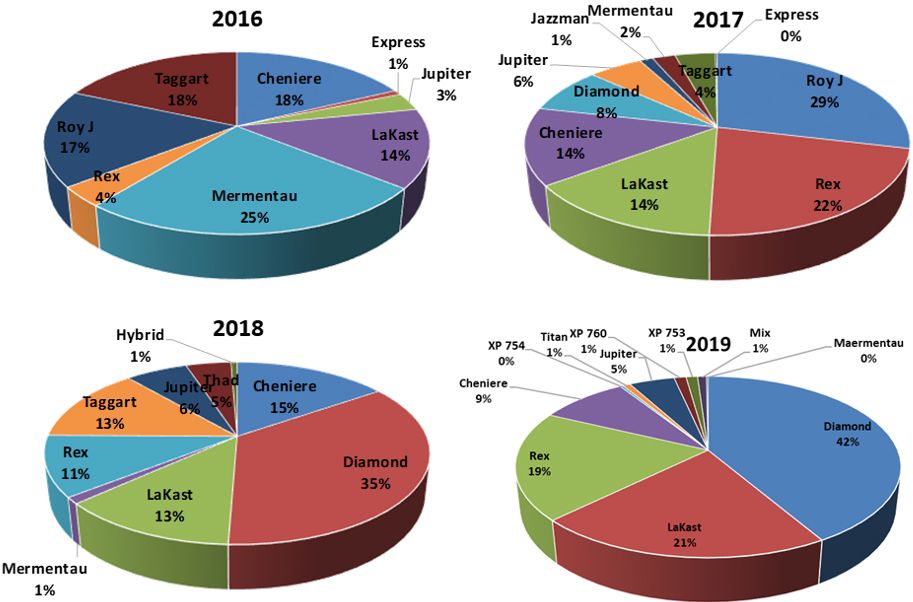

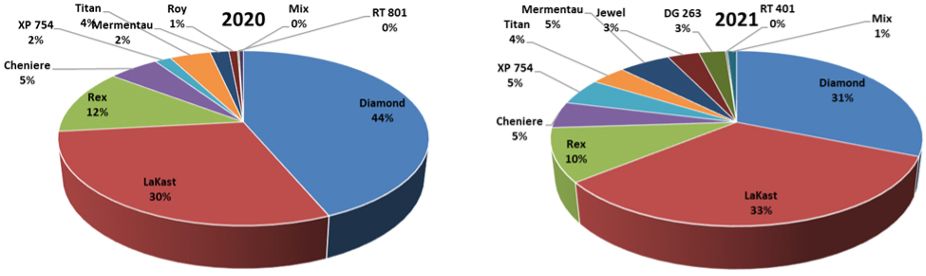

To provide a continual influx of new varieties, UF/IFAS and FCC conduct annual rice variety trials to rate new or existing varieties in south Florida. Varieties developed from other breeding programs are planted in small-plot variety assessment trials, and parameters including yield quality/quantity and disease susceptibility are ranked by variety. Varieties ranking high over multiple years are introduced into commercial production. Due to the efforts of these rice variety trials, the diversity of rice varieties planted in south Florida has steadily increased from three varieties (Wells, Cypress, Jupiter) in 2008 (Figure 3) to seven varieties in 2015 (Roy J, Mermentau, Taggart, Cheniere, Wells, Jupiter, Rex) (Figure 4), nine varieties in 2018 (Jupiter, Diamond, LaKast, Cheniere, Rex, Thad, Mermentau, Taggart, and Hybrid varieties) (Figure 5), and eleven varieties as of 2021 (Figure 6), which also include more hybrid varieties as compared to previous years. In addition, acreage by variety was more uniform in 2015 than in previous years. Description of some of the varieties tested in Florida are summarized in Table 1.

Credit: Dr. Jehangir H. Bhadha, UF/IFAS; Luigi Trotta, King Ranch Inc.; and Dr. Matthew VanWeelden, UF/IFAS

Credit: Dr. Jehangir H. Bhadha, UF/IFAS; Luigi Trotta, King Ranch Inc.; Daniel Cavazos, Florida Crystals Corporation; and Dr. Matthew VanWeelden, UF/IFAS

Credit: Dr. Jehangir H. Bhadha, UF/IFAS; Luigi Trotta, King Ranch Inc.; Daniel Cavazos, Florida Crystals Corporation; and Dr. Matthew VanWeelden, UF/IFAS

Credit: Dr. Jehangir H. Bhadha, UF/IFAS; Luigi Trotta, King Ranch Inc.; Daniel Cavazos, Florida Crystals Corporation; and Dr. Matthew VanWeelden, UF/IFAS

In 2009, 86% of rice planted in Florida was of a single variety (Wells), leaving the industry dependent on the continued success of this variety. This situation emphasizes the need to have multiple varieties available if a variety fails because of adverse biotic or abiotic conditions. In 2015, the top two varieties (Roy J and Mermentau) of rice covered only 62% of the total acreage of planted rice in the EAA. In 2021, the top two varieties (Diamond and LaKast) of rice covered only 64% of the total acreage of planted rice in the EAA (Figure 7). Studies conducted by Louisiana State University on rice varieties refer to Roy J and Mermentau as long-grain rice varieties. Typically, the varieties tested in Florida are long- to medium-grain rice. Roy J has shown excellent yield potential, and Mermentau has shown good seedling vigor and ratoon crop potential (Saichuck et al. 2015). In 2018, the top two varieties planted were Diamond and Cheniere, representing almost 50% of the total planted acreage, while in 2021, Diamond was still the dominant variety.

Credit: Dr. Jehangir H. Bhadha and Matthew VanWeelden, UF/IFAS

Conclusion

There has been an increasing trend in rice production within the EAA from 2008 to 2021. As the acreage of planted rice increases, so does the number of varieties that are being planted. While only two dominant varieties were planted in 2008 across 11,912 ac, eleven varieties were planted across 23,058 ac in 2021. Increasing trends in rice acreage and available varieties are testaments that growers in the EAA prefer planting flooded rice in the summer months rather than managing flooded fallow fields.

Table 1. Brief description of the recent rice varieties tested in Florida.

References

Alvarez, J., G. Kidder, and G. Snyder. 1978. “The Economic Potential of Growing Rice and Sugarcane in Rotation in the Everglades.” Proceedings of the Soil and Crop Science Society of Florida 38: 12–15.

Bhadha, J. H., A. L. Wright, and G. H. Snyder. 2020. “Everglades Agricultural Area Soil Subsidence and Sustainability: SL311/SS523, rev. 2020.” EDIS 2020 (2). https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-ss523-2020

Bhadha, J., R. Khatiwada, S. Galindo, N. Xu, and J. Capasso. 2018. “Evidence of Soil Health Benefits of Flooded Rice Compared to Fallow Practice.” Sustainable Agriculture Research 7 (1): 31–41. https://doi.org/10.5539/sar.v7n4p31

Cherry, R., M. Tootoonchi, J. Bhadha, T. Lang, M. Krounos, and S. Daroub. 2015. “Effect of Flood Depth on Rice Water Weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) Populations in Florida Rice Fields.” Journal of Entomological Science 50 (4): 311–317. https://doi.org/10.18474/JES15-05.1

Norman, R. J., and K. A. K. Moldenhauer, eds. 2019. “B. R. Wells Arkansas Rice Research Studies 2018.” Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station Research Series 154. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/aaesser/154

Saichuk, J., S. Brown, B. Courville, D. Groth, D. Harrell, C. Hollier, S. Linscombe, et al. 2015. Rice Varieties and Management Tips. Publication 2270. Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Ag Center. https://www.lsuagcenter.com/articles/connected/rice-varieties-and-management-tip

Schueneman, T., C. Rainbolt, and R. Gilbert. 2005. Rice in the Crop Rotation. SS-AGR-23. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00001556/00001/pdf