A Changing Climate for Conservation

Climate change is creating new challenges for conservation and management of natural resources. As temperatures, rainfall patterns, and disturbance regimes change and sea levels rise, ecosystems are being transformed. Some species of plants and animals are already shifting their distributions in response to climate change, and changes in phenology are disrupting ecological relationships and species interactions. Some organisms also respond physiologically to increasing temperatures and CO2 concentrations.

These changes are raising questions about the effectiveness of traditional strategies for conserving natural resources. The missions of conservation agencies typically involve protecting particular species and ecosystems within fixed systems of protected areas. However, with climate change species and communities may "move out" of the reserves that were established to protect them, and may not have the needed migration corridors to successfully disperse. The rate at which climate is projected to change in coming decades is likely too fast for many species to genetically adapt or to migrate (through increasingly fragmented landscapes) to new suitable areas.

Climate change underscores the need, apparent to many in the conservation community, to transform our perspective from a static and stable view of the natural world to one that is dynamic and accepting of uncertainty. While many of our conservation tools and approaches will stay the same, a new perspective will enable us to better apply these tools to meet future challenges. This fact sheet summarizes recommendations from four recent reviews of the literature on climate change "adaptation" (Glick et al. 2009, Heller and Zavaleta 2009, Lawler 2009, West et al. 2009).

Credit: Duncan Wright, USFWS

Credit: USFWS

Climate Change Adaptation Strategies: Familiar Tools

Climate change adaptation is defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as "initiatives and measures designed to reduce the vulnerability of natural and human systems against actual or expected climate change effects" (IPCC 2007). To alleviate confusion with the ecological meaning of adaptation, this is sometimes called "planned" or "managed" adaptation to climate change.

The most prominent strategies for climate change adaptation are summarized in the list below. These approaches share an overall emphasis on promoting both system resistance (ability to withstand environmental change) and resilience (ability to bounce back from, or absorb, environmental change). A complete adaptation strategy, according to the literature, should involve a combination of measures, from short-term to long-term and from precautionary to more risky:

- Reduce non-climate stressors such as habitat loss, invasive species, and pollution

- Expand networks of protected areas

- Increase landscape connectivity with habitat buffer zones and wildlife corridors to facilitate species dispersal

- Manage for ecological function and protection of biological diversity

- Restore degraded habitats and ecosystems

- Implement proactive management and restoration strategies to enable ecosystems and habitats to accommodate climate change

- Consider translocation or "assisted migration" for species with limited dispersal ability or small, isolated ranges

- Expand monitoring programs and facilitate management under uncertainty

Credit: USFWS

Implementing Adaptation Strategies: New Perspectives

Most of the adaptation strategies listed above are not new but rather are well-established approaches to protect biodiversity. These traditional conservation tools will be critical to maintain basic ecosystem functioning and mitigate other threats in the face of climate change. However, how these tools will be applied as a systematic, unified approach to address climate change is still largely undefined and untested.

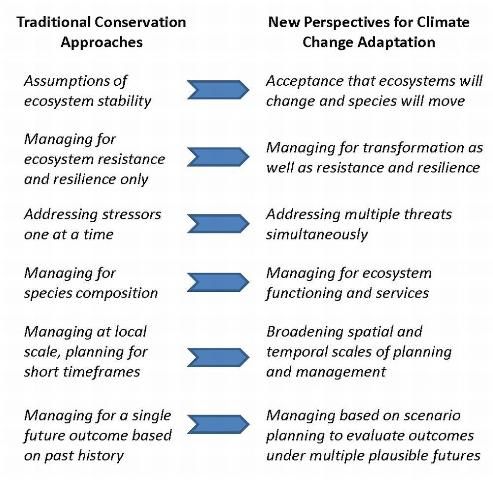

The adaptation literature recommends that the conservation community make broad administrative changes including incorporating climate change into all conservation and planning actions; and increasing coordination among scientists, land managers, politicians and conservation organizations at regional scales. In addition, to effectively implement climate change adaptation strategies we may need to make fundamental shifts in the way we collectively think about conservation (Figure 1).

As climate change will further stretch the already limited resources of agencies and conservation organizations, re-evaluating priorities and developing a triage system will become increasingly necessary. Some species or systems may be given higher conservation priority based on their ecological or societal value, severity of climate impact, and feasibility of management. Vulnerability assessments will help us better understand sensitivities and adaptive capacities of species and ecosystems to climate change impacts. Modeling tools and methods are continually being refined to forecast how climate is changing and how species, ecosystems, and disturbance regimes are likely to respond to these changes. Efforts to generate climate model data at finer resolutions and more local scales will help resource managers match the scale of climate projections to the scale of on-the-ground management plans and biological responses.

Credit: Gerald and Buff Corsi © California Academy of Sciences

Continual applied research efforts are needed to determine which of the potential climate change adaptation strategies will work best in each specific context. Research into how climate change will affect ecosystem services will further help in valuing conservation and designing management and restoration plans. Adaptive management, an organized system of learning that allows for continual incorporation of new information, is likely to be more important than ever given the uncertainty inherent in planning for climate change. Incorporating scenario planning into an adaptive management framework can help increase flexibility of management approaches in dealing with future uncertainties. Particular attention should be paid to the development of sound scientific hypotheses, targeted monitoring programs, and frequent re-evaluation of management approaches.

Literature Cited

Glick, P., A. Staudt, and B. Stein. 2009. A New Era for Conservation: Review of the Climate Change Adaptation Literature. National Wildlife Federation.

Heller, N. E., and E. S. Zavaleta. 2009. Biodiversity management in the face of climate change: a review of 22 years of recommendations. Biological Conservation 142:14–32.

IPCC. 2007. Climate Change 2007. Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. B. Metz, et al. (eds), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lawler, J. J. 2009. Climate change adaptation strategies for resource management and conservation planning. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1162:79–98.

West, J. M., S. H. Julius, P. Kareiva, C. Enquist, J. J. Lawler, B. Petersen, A .E. Johnson, and M. R. Shaw. 2009. U.S. natural resources and climate change: concepts and approaches for management adaptation. Environmental Management 44:1001–1021.