Introduction

Florida's beautiful parks and woodlands are favorite places for many people who enjoy outdoor activities. Unfortunately, a few native plants—namely poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac, and poisonwood—can make these outings a miserable experience (Figure 1). All four contain urushiol, a plant oil that can cause a severe skin rash (dermatitis) when any part of the plant is contacted. Allergic reaction can occur directly by touching the plant or indirectly by coming into contact with the oil on animals, tools, clothes, shoes, or other items. Even the smoke from burning plants contains oil particles that can be inhaled and cause lung irritation.

Credit: Cook (2012); Larry Korhnak, UF/IFAS

Individuals vary in their susceptibility to these plants. Some people are not sensitive, but may become sensitive after repeated exposure. Symptoms appear within 8–48 hours and can last for weeks. Itching and burning of the skin may be followed by a rash, redness, swelling, and watery blisters. The rash, which can last 2–5 weeks, is not contagious and will not spread. Systemic complications can occur if the blisters become infected.

Over-the-counter skin creams containing the active ingredient bentoquatam (for example, Ivy Block®) absorb the urushiol oil and can prevent or lessen a reaction if applied before contact. If exposed to the urushiol oil in one of these plants, immediately cleanse exposed skin, tools, shoes, or other items with plenty of warm, soapy water and then rinse thoroughly with plain, cool water. Clothes should be washed thoroughly and separately from other laundry. Minor rashes can be cared for at home with over-the-counter treatments that contain zinc acetate, hydrocortisone, or zinc oxide; oatmeal baths; a paste of baking soda; or oral antihistamines. Severe or infected rashes may need professional medical treatment.

Interaction with these plants is largely preventable. This publication helps individuals learn to identify these plants in order to avoid contact with them. Children should be taught to recognize these plants, particularly poison ivy, as it is by far the most common. Keep in mind that poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac are deciduous, making identification difficult in winter. Nevertheless, the sap from leafless stems and roots is still problematic. Other poison ivy relatives that grow in Florida and may also cause allergic reactions include mango (Mangifera indica) (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg216), cashew (Anacardium occidentale) (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/hs377), and the highly invasive Brazilian pepper-tree (Schinus terebinthifolius) (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/aa219).

Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

Poison ivy grows in shady or sunny locations throughout Florida. It can be a woody shrub up to 6 feet tall or a vine up to 150 feet tall that climbs high on trees, walls, and fences or trails along the ground (Figure 2). All parts of poison ivy, including the hairy-looking aerial roots, contain urushiol at all times of the year, even when bare of leaves and fruit in winter. Plants are frequently abundant along old fence rows and the edges of paths and roadways. Leaf forms are variable among plants and even among leaves on the same plant; however, the leaves always consist of three leaflets. The old saying "Leaflets three, let it be" is a reminder of this consistent leaf characteristic. Leaflets can be 2–6 inches long and may be toothed or have smooth edges. The stem attaching the terminal leaflet is longer than stems attaching the other two. Leaves emerge with a shiny reddish tinge in the spring and turn a dull green as they age, eventually turning shades of red or purple (Figure 3) in the fall before dropping.

Credit: UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants

Credit: UF/IFAS

Flowers and fruit are always in clusters on slender stems that originate in the leaf axils (angles), between the leaves and woody twigs. The berrylike fruits are round and grooved with a white, waxy coating. They are attractive to birds. The leaves and fruit are an important food source for deer (Figure 4).

Credit: Cook (2012)

A common poison ivy look-alike is the native Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) (Figure 5). This trailing or climbing vine can be distinguished from poison ivy rather easily by its five divided palmate leaflets. Other distinguishing features include blue-black berries and tendrils that end in tiny sticky pads that attach to trees and other surfaces. In winter, the leaves of Virginia creeper turn red and drop from the plant (Figure 6). For more information, see https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fp454.

Credit: Larry Korhnak, UF/IFAS

Credit: Sydney Park Brown, UF/IFAS

Poison Oak (Toxicodendron pubescens)

Poison oak, also known as Atlantic poison oak, oakleaf ivy, or oakleaf poison ivy, is a low-growing, upright shrub that is about 3 feet tall. It is found in dry, sunny locations and does not tolerate heavy shade. Poison oak is confirmed in north and central Florida, from Levy and Marion Counties northward.

Like poison ivy, a single poison oak leaf consists of three leaflets. The stem attaching the terminal leaflet is longer than the stems attaching the other two. One distinguishing feature of poison oak is its lobed leaves, which give it the appearance of an oak leaf. The middle leaflet usually is lobed alike on both margins, and the two lateral leaflets are often irregularly lobed (Figure 7). Leaf size varies considerably, even on the same plant, but leaves are generally about 6 inches long. Another distinguishing feature is that the leaf stems and leaflets have a coating of fine hair.

Leaflets emerge with a reddish tinge in the spring, turn green, and then assume varying shades of yellow and red in the fall before dropping. As with poison ivy, the flowers and fruit arise from the leaf axils in clusters. The small flowers are white, and the ripe fruit is round, light tan, waxy, and grooved (Figure 8).

Credit: Larry Korhnak, UF/IFAS

Credit: Cook (2012)

Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix)

Credit: Cook (2012)

More allergenic than poison ivy and poison oak is poison sumac, a deciduous woody shrub or small tree that grows 5–20 feet tall and has a sparse, open form (Figure 9). It inhabits swamps and other wet areas, pine woods, and shady hardwood forests. In Florida, poison sumac has been confirmed in the north and central regions, as far south as Polk County.

Credit: Larry Korhnak, UF/IFAS

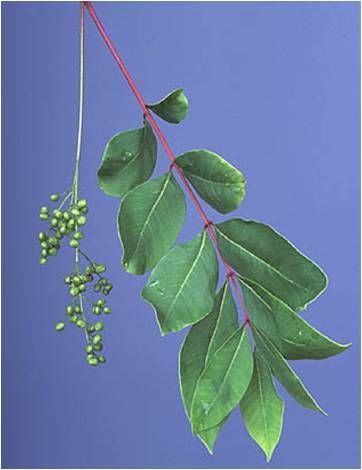

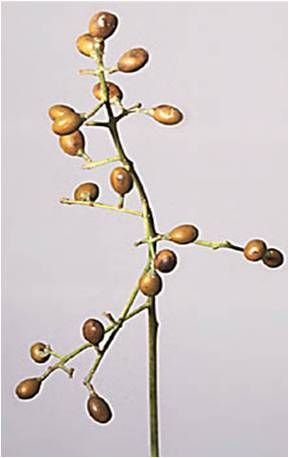

Poison sumac leaves consist of 7–13 leaflets arranged in pairs with a single leaflet at the end of the midrib. Distinctive features include reddish stems and petioles (Figure 10). Leaflets are elongated, oval, and have smooth margins. They are 2–4 inches long, 1–2 inches wide, and have a smooth, velvety texture. In early spring, the leaves emerge bright orange. Later, they become dark green and glossy on the upper leaf surface and pale green on the underside. In the early fall, leaves turn a brilliant red-orange or russet shade. The small, yellowish-green flowers are borne in clusters on slender stems arising from the leaf axils. Flowers mature into ivory-white to gray fruits resembling those of poison oak or poison ivy, but they are usually less compact and hang in loose clusters of up to 10–12 inches in length (Figure 11).

Credit: Cook (2012)

Winged sumac (Rhus copallinum) has a similar appearance but is a nonallergenic relative that grows throughout Florida. It can be distinguished from poison sumac most readily by its 9–23 leaflets, clusters of red berries, and the winged rachis between the leaflets (Figure 12).

Credit: Larry Korhnak, UF/IFAS

Poisonwood (Metopium toxiferum)

Poisonwood is an evergreen shrub or tree that grows 25–35 feet tall in hammocks, pinelands, and sandy areas near saltwater. It is particularly abundant in the Florida Keys. As of this writing, poisonwood's range has only been confirmed in five counties in South Florida: Martin, Palm Beach, Broward, Miami-Dade, and Monroe. The tree has a spreading, rounded form with a short trunk and arching limbs with drooping branches. The bark varies in color from reddish brown to gray, depending on the habitat, and has oily patches of sap on the surface; older trees have scaly bark (Figure 13). Each leaf is composed of three to seven oval leaflets, although five leaflets are typical. Leaves are glossy and dark green above, paler underneath, and have smooth margins (leaf edges). Irregular blotches of resin dot the surface of many of the leaflets (Figure 14). The fruit is ½ inch long, oval, yellow to orange in color, and hangs in loose clusters (Figure 15). The poisonwood fruit is an important food source for the threatened white-crowned pigeon.

Credit: Kim Gabel, UF/IFAS

Credit: Kim Gabel, UF/IFAS

Credit: Larry Korhnak, UF/IFAS

Do not walk where poisonwood is known to grow during a rainstorm. Rainwater dripping off the poisonwood leaves contains urushiol, which causes contact dermatitis.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Mary Derrick, former horticulture program assistant, for her help with the research and editing of this publication, and Dan Culbert, retired UF/IFAS Extension Okeechobee County horticulture agent, as well as Kim Gabel, UF/IFAS Extension Monroe County horticulture agent, for their reviews and contributions. The original publication was written by Pat Grace, former UF/IFAS Extension Putnam County horticulture agent and Sherrie Lowe, Putnam County Master Gardener; UF/IFAS Extension, Gainesville, FL 32611.

Reference

Cook, W. 2012. "Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines of North Carolina." Accessed February 2012. https://www.duke.edu/~cwcook/trees/.

Additional Resources

Hossler, E. W. 2010. "Botanical Briefs: Poisonwood (Metopium toxiferum)." Cutis 85(4): 178–179.

Institute for Systemic Botany. 2012. "Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants." Accessed February 2012. https://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/

Mayo Clinic Online. 2012. "Poison Ivy Rash." Accessed March 2012. https://www.mayoclinic.com/health/poison-ivy/DS00774

MedLine Plus. 2012. "Poison Ivy – Oak – Sumac Rash." Accessed February 2012. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000027.htm

Nellis, D. W. 1997. Poisononus Plants and Animals of Florida and the Caribbean. Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press.

UF/IFAS (University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences). 2012. "Forest Trees and Companion Plants." Accessed March 2012. https://www.sfrc.ufl.edu/4h/Trees_Plants/trees_plants.html