Citrus greening, or huanglongbing (HLB), is a bacterial disease that affects citrus trees' vascular systems, limiting nutrient uptake. As trees become increasingly affected by the disease, they suffer premature fruit drop, the fruit harvested is smaller and misshapen, and the juice quality is compromised, all resulting in lower yield. To this date there is no cure or successful management strategy to deal with HLB. From an economic standpoint, the major impact of HLB at the farm-level has been the increase in cost of production per box.

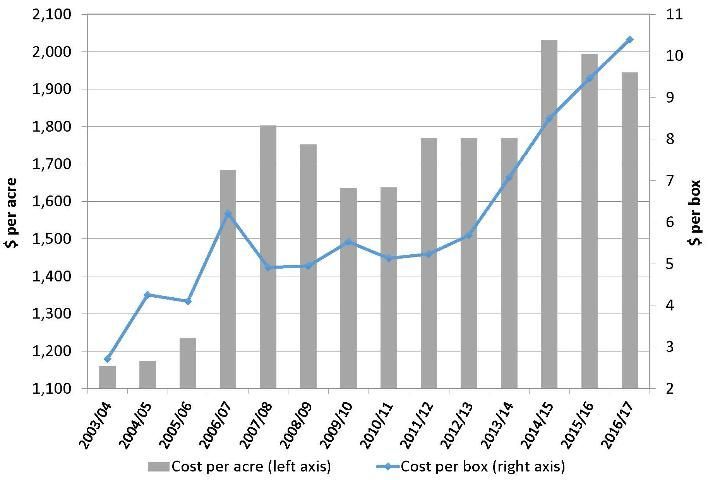

The real cultural production costs for processed oranges in southwest Florida on a per-acre basis increased from $1,161 in 2003/04 to $1,944 in 2016/17, up 67% during that period (Figure 1). Such an increase in cost was mainly due to growers using more foliar sprays and fertilizer in an attempt to bypass the trees' vascular blockages (Singerman and Burani-Arouca 2017). However, Figure 1 also shows that, on a per-box basis, real cultural production costs increased from $2.71 in 2003/04 to $10.40 in 2016/17, which represents a 283% increase (Singerman 2018). The reason for the higher percentage increase on a per-box basis is due to the simultaneous increase in cost per acre and decrease in yield per acre. The decrease in supply of oranges due to HLB (as economic theory predicts) caused on-tree prices per box to increase. But such increase in real prices was by 122% (USDA-NASS 2018). Thus, the greater increase in cost per box relative to price has resulted in lack of profitability for the average grower, particularly during the last few seasons (Singerman, Lence, and Useche 2017).

Credit: UF/IFAS Citrus Research and Education Center, Multiple Annual Cost of Production reports. Cost of production per box are the authors' calculations.

As a consequence of the lack of profitability, the industry has been downsizing (Singerman, Burani-Arouca, and Futch 2018). To prevent more growers and infrastructure from going away, and to keep the Florida citrus industry afloat until a cure or management strategy for HLB is found, several public and private incentive programs for replanting have been made available to growers (Singerman 2017). Such programs can incentivize growers to invest in a new citrus grove. However, a key question is whether current practices are profitable in the current environment, in particular the typical grove planting density.

The purpose of this article is to summarize the results of an analysis we performed to examine the profitability of three tree densities under different production and market conditions. In agreement with what many growers across the state are currently experiencing, we found that establishing a new grove with a tree density similar to that of the state's average is not profitable under current market conditions. In addition, such density only attains a modest return under potentially higher prices. Despite the higher level of investment required for planting higher-density groves, such investments are profitable under the assumptions and scenarios analyzed. Our results should prove useful to citrus growers looking to invest in alternatives that have the potential to improve their profitability. In addition, results should also help policy makers design incentive planting programs that take such higher investments into account.

Assumptions

Our analysis is for Valencia oranges, which is the predominant late variety produced in Florida, accounting for approximately 55% of the bearing acreage of oranges grown in the state during the last few years. The choice of this variety determines the values for yields and prices used in our model. Our cost estimates, however, are also applicable to early varieties. The basis for our annual estimates on cost of production is the survey data collected in southwest Florida in 2016/17 for growing processed oranges (Singerman 2018). As is typical for developing Extension budgets, our computations and analysis are for one representative acre. However, for the purposes of calculating the necessary investment in machinery and associated fixed costs, we assume the operation has 250 net acres; smaller operations would likely find it more cost effective to hire caretakers to perform the cultural practices.

The tree density baseline for our analysis is 145 trees per acre, which is the average tree density reported by growers participating in the survey, and which is also similar to the state average for a citrus grove in Florida (USDA-NASS, 2017). The between-rows and between-trees spacing associated with 145 trees per acre is 25 by 12 feet, respectively. We also analyzed two higher tree densities, namely 220 trees per acre (with 22 by 9 feet spacing between rows and trees, respectively) and 303 trees per acre (with 18 by 8 feet spacing between rows and trees, respectively). These two higher densities are based on the feedback we obtained from growers that have already planted high-density groves.

Irrigation and frost protection are a key component of the investment in a new grove. Thus, to estimate such an investment, the first step was to determine the quantity of water needed for each tree density. The per-tree water needs for a grove with 140 trees per acre are 14 and 39 gallons per day for winter and summer months, respectively, whereas a grove with 218 trees per acre will need 9 and 25 gallons per tree per day for winter and summer months, respectively (Parsons and Morgan 2017). To compute the water required to irrigate a grove with 303 trees per acre, we extrapolated the water requirements based on the percentage of additional trees with respect to 220 trees per acre, taking into account a reduction in per-tree water needs; we found the per-tree water needs for a grove planted at 303 trees per acre to be 7 and 19 gallons per day for winter and summer, respectively. We then established the volume of annual irrigation needed by taking into account the amount of water that trees receive from rainfall. We estimated the historical average rainfall in three representative citrus-growing cities in Florida from 2010 to 2016 using data from the Florida Automated Weather Network (FAWN). Then, based on the gallons of water needed per day per tree for each tree density, we calculated the average amount of irrigated water needed each month to supplement rainfall.

To account for frost protection, we assumed four radiation frost events per year based on Jackson, Morgan, and Lusher (2015). During each event, the irrigation system was assumed to be run for 12 continuous hours. We assumed a 50-acre irrigation zone based on feedback from irrigation supply companies. We also made assumptions regarding the use of microsprinklers, which in turn affected the decision of the capacity of the water-well and pump needed, which is different for each tree density. Then we gathered appropriate quotes for the equipment and computed the variable costs associated with the irrigation system (such as pumping hours and diesel consumption, repairs, and maintenance using feedback from suppliers).

We assume that the average expected lifespan of a grove in Florida has decreased from 30 to 20 years as a consequence of the impact of HLB. The disease has also affected tree mortality, which we assume to be 3% in years 2 through 6 and 5% from years 7 through 20. These figures are based on growers' feedback. However, the tree replacement strategy for removed trees is based on a sensitivity analysis that maximizes profit. In our model, we also assume that the following cultural activities are contracted: land preparation and bedding, fertilization, hedging and topping, tree removal, and tree replacement. Regarding the land, we assume it is already owned.

Within cultural cost of production, foliar sprays are the largest expense in the caretaking of groves, accounting for 34% of the total (Singerman 2018). Because we assume the use of tree-sensing technology for the application of foliar sprays, we wanted to obtain the cost of materials per tree by age. To calculate such cost per tree, we divided the cost per acre of the foliar sprays program by the total number of trees in the year in which trees reach maturity. Taking into account the HLB-stunting effect on citrus trees, we assumed it would take 12 years for them to reach full growth (height). Thus, the material application rate for trees between 1 and 11 years old was computed taking into account a percent reduction relative to mature trees based on their age (and height). Once we obtained the cost per tree by tree age, we computed the foliar sprays costs per acre for each year by simply multiplying the number of trees in each age cohort by the associated foliar spray cost per tree.

Fertilizer is the second-largest expense in the caretaking of the groves, which accounted for 21% of the cultural cost of production in 2016/17 (Singerman 2018). To compute the cost of the annual fertilizer program, we also wanted to obtain fertilization rates per tree. To calculate such rates per tree, we divided the cost per acre of the program by the total number of trees 4 years old and older in year 12. Mature trees receive 100% of the rate that is associated with the survey cost data. However, to compute the cost of fertilizing younger trees we did the following. For trees 1, 2, and 3 years old, we based fertilizer applications on UF/IFAS recommendations (Morgan et al. 2017) that specify using three dry fertilizer applications and eight liquid fertilizer applications. For trees between 4 and 11 years old, we computed a reduction in their material application rate relative to a mature tree based on their height.

To compute the cost of the fertilizing program for tree densities 220 and 303, we calculated the cost per tree in a similar fashion to that described above. However, since fertilizer recommendations are on a per-acre basis, we applied a cap equal to the cost of the mature trees' program in the 145 tree density. Regarding the annual application cost per acre for dry fertilizer, we included an application cost upcharge of 11% and 44% for 220 and 303 trees per acre, respectively. Such upcharges are based on the extra cost of fuel and labor involved in the applications due to the additional number of rows per acre in higher-density groves relative to the 145-trees-per-acre density.

Scenario Analysis

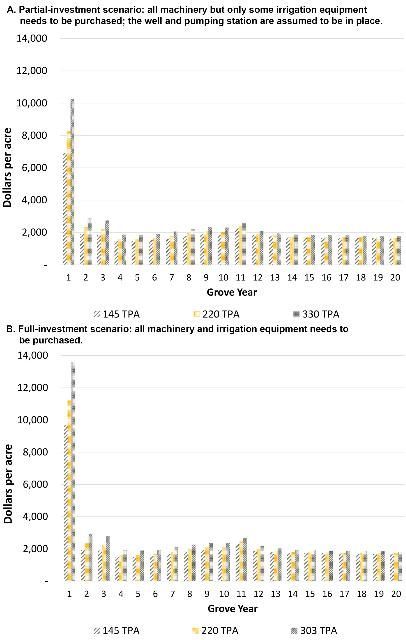

To allow for the possibility of different types of growers planting a new grove, we also made assumptions regarding the level of investment needed in terms of machinery and irrigation. We assume such investment could be either full or partial so as to represent the cases of a new grower and that of a current grower, respectively. The difference between the two scenarios is that, in the full-investment scenario, the grower needs to purchase all machinery and irrigation equipment required to manage the grove, whereas in the partial-investment scenario, the grower only needs to make some investment in irrigation (the well and pumping station are assumed to be in place already). However, in both scenarios we assume that the grower needs to purchase a new tractor, ATV, and pickup truck in year 11. The rest of the machinery is assumed to be used beyond its accounting lifespan of 10 years.

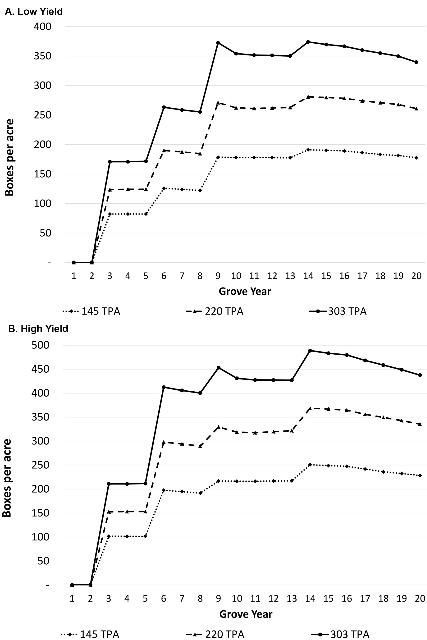

Yield is a key parameter in the model, and we assume two possible scenarios for it. In both scenarios, trees start to fruit 26 months after planting. In the first scenario, which we refer to as low, we assume that the boxes per tree for each of the different age cohorts are given by the USDA-NASS average for southwest Florida during seasons 2013/14 through 2015/16. Such estimates represent approximately a 40% yield reduction compared to pre-HLB yield levels, which is in agreement with the average loss reported by growers (Singerman and Useche 2017). In the second scenario, which we refer to as high, we assume trees yield more boxes relative to scenario 1 based on the feedback from growers we visited with—who attain yields that are higher than the state's average. Regarding yield quality, we assume that in both scenarios each box yields 6.24 pound solids (ps) (FDOC 2017a).

Price is another key parameter in the model. The average delivered-in price for Valencia (late season) oranges in 2016/17 was $2.85/ps (FDOC 2017b). To obtain the on-tree price (which is the price the grower receives) from the delivered-in price, we subtract $3.27/box (Singerman et al. 2017) for harvesting and $0.07/box for FDOC assessment from delivered-in prices and obtain $2.31/ps. We model three scenarios to represent possible market conditions: low, medium, and high prices. Thus, we use the on-tree price estimate as the medium price scenario and assumed a 15% decrease (10% increase) with respect to such price to establish the low (high) scenario of $1.97/ps ($2.55/ps); these translate into delivered-in estimates of $2.50/ps and $3.08/ps, respectively. These prices were chosen so as to represent a range of conservative current and future potential market conditions. For simplicity, we assume that prices are constant throughout the investment period. We assume that the annual cash flows are expressed in real terms, so we do not need to adjust them for inflation. Thus, the resulting rates of return are to be interpreted in real terms as well.

Results

By combining the investment requirement (full or partial), cost of production, yields, and prices described in the previous section, we obtained a set of different scenarios for each tree density. Thus, we computed a financial budget for each scenario, which is the basis for the investment analysis; the typical methodology for establishing the profitability of an investment.

Interestingly, annual expenses for higher tree densities do not increase proportionally with the number of trees planted. Figure 1 shows the cash expenses for each of the three tree densities throughout the 20-year investment period. Panel A of that figure denotes the expenses for the partial-investment scenario and panel B for the full-investment scenario. In the partial-investment scenario, expenses in year 1 are $6,908, $8,253, and $10,265 per acre for 145, 220, and 330 trees per acre, respectively. The latter two are 19% and 49% higher relative to the 145-trees-per-acre baseline. In years 2 and 3, expenses for the 220 and 303 tree densities decrease but are still approximately 20% and 50% higher with respect to those of a grove planted at 145 trees per acre. However, in years 4 through 11, expenses are approximately between 7% to 10% higher for the 220-trees-per-acre density, and 16% to 28% higher for the 303-trees-per-acre density compared to the baseline. Starting in year 12, expenses are only up to 6% and 15% higher for the 220- and 303-trees-per-acre density, respectively, compared to the 145 density baseline. As shown in Figure 2 panel B, results for the full investment scenario show a similar trend.

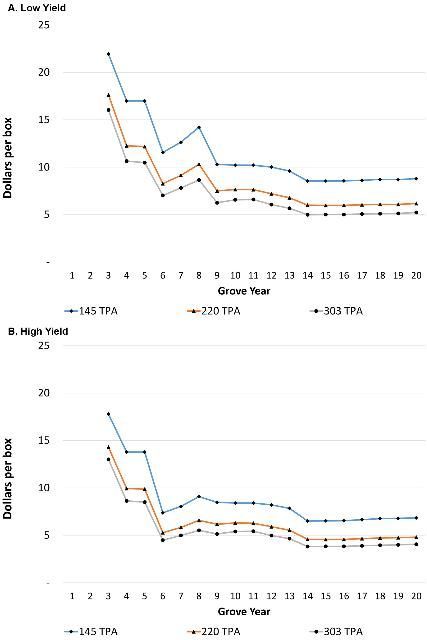

Yield per acre increases proportionally to the higher number of trees planted. Such proportional increase is imposed by assumption because, as described above, we use data on yield per tree from USDA-NASS (2017) for our calculations. However, starting in year 10, the proportional change decreases due to the effect of the penalty we impose for canopy closure (3.5% and 5% for the 220 and 303 densities, respectively) and resetting strategy for the higher densities. Figure 2 shows yield per acre by grove year for each of the three tree densities under the low and high scenarios and illustrates the proportional increase in yield for tree densities 220 and 303 relative to the 145-tree-density baseline.

Credit:

We use investment analysis to evaluate the profitability of the long-term investment in an orange grove. The Net Present Value (NPV) can be used as a methodology for such evaluation, which consists in summing all the discounted cash flows as denoted by the equation below.

Credit:

In the equation, CF is the cash flow at time n, and r denotes the discount rate. The choice on the latter is key because it represents the cost of capital (or its opportunity cost). As a rule of thumb, investments with a positive NPV should be accepted, and those with a negative NPV, rejected. The rationale for accepting investments with positive NPVs is that they yield higher returns than the discount rate (i.e., cost of capital). However, it is impossible to estimate a discount rate that would represent the cost of capital for all growers; each individual grower has a different opportunity cost of capital. Therefore, we show the results of the investment analysis using the internal rate of return (IRR) methodology. The IRR is the actual rate of return on the investment; it is the discount rate that makes the NPV be zero in the equation above. As such, it depends only on the cash flows of the investment (Ross, Westerfield, and Jaffe 2005).

Table 1 shows the results of the investment analysis for the different scenarios and tree densities. Table 1 panel A shows that in a grove with 145 trees per acre, under a scenario with low yield and low prices, the investment is not profitable; with medium prices, the partial-investment scenario yields an IRR of 1%. Table 1 panel A also shows that, when prices are high, there is a modest return between 1% and 3% depending on the level of investment in machinery and irrigation. Under a high-yield scenario, the IRR of a grove with 145 trees per acre varies from 1 up to 10% depending on the combination of prices and investment requirement. The payback period is 12 years in the best-case scenario.

Despite the higher initial investment relative to the 145 baseline, Table 1 panel B shows that in a grove with 220 trees per acre, the IRR is positive. Under a low-yield scenario, the IRR ranges between 2% to 10%, depending on market conditions and the level of investment required. The payback period is at least 12 years. Under a high-yield scenario, depending on the level of prices and investment, the IRR ranges from 8% to 17%, and the payback period can be as low as 8 years in the best-case scenario.

Table 1 panel C shows the IRR for a grove with 303 trees per acre improved even further beyond those obtained for 220 trees per acre (despite the even higher level of initial investment relative to the baseline). Under a low-yield scenario, the rate of return ranges between 5% to 13% depending on market conditions and the level of investment needed. In a high-yield scenario, depending on prices and the investment required, the IRR ranges from 11% to 20%, and the payback period can be as low as 8 years in some cases.

The main driver for the results discussed above is that while the costs of higher-density groves do not increase proportionally with the number of trees, yield per acre does. More specifically, while in a higher-density grove each tree produces somewhat less yield compared to a tree in a lower-density grove, the higher number of trees contributes to obtain a higher yield per acre. Therefore, planting higher-density groves could help offset some of the impact of HLB by decreasing the cost of production per box due to costs being allocated to a higher number of boxes (Figure 4), ultimately resulting in an increase in profitability per acre.

Credit:

Credit:

Conclusions and Limitations of the Analysis

After analyzing the investment on a new grove in southwest Florida under the current endemic HLB environment, we found that a grove with a tree density similar to that of the state's average is not profitable under current market conditions. Moreover, such tree density only attains a modest return under potential higher prices. However, despite the higher level of investment required for planting 220 and 303 trees per acre, our analysis shows that under the assumptions and scenarios we analyzed, those investments yield positive returns.

The limitations of this analysis are the following. First, because HLB was first found in Florida in 2005, it is not yet clear how trees will be affected by the disease in the future. Therefore, in our model, the impact of HLB on yield of trees that are 13 years old and older is a projection based on current data. Second, we did not include any potential impact of weather events such as freezes or hurricanes (and their effect on prices and yield) in our analysis. Third, potential future management strategies or solutions to HLB could involve planting (new) trees with resistant or tolerant traits to the disease, which could make an existing grove with trees that do not have such traits obsolete.

Excel spreadsheets containing the analysis presented in this article can be downloaded at the website listed below. In addition, once downloaded, the user can customize some of the estimates to make the analysis applicable to their own operation.

References

Florida Department of Citrus (FDOC). 2017a. Processor Report July 17, 2017.

Florida Department of Citrus (FDOC). 2017b. Post Estimate Fruit Price Report 06.03.17.

Jackson, J. L., K. Morgan, and W. R. Lusher. 2015. SL 296. Citrus cold weather protection and irrigation scheduling tools using Florida Automated Weather Network (FAWN) data. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Morgan, K. T., D. M. Kadyampakeni, M. Zekri, A. W. Schumann, T. Vashisth, and T. A. Obreza. 2017. "Nutrition Management for Citrus Trees." 2017–2018 Florida Citrus Production Guide. UF/IFAS Extension, University of Florida.

Parsons, L. R. and K. T. Morgan. 2017. HS958. Management of Microsprinkler Systems for Florida Citrus. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Ross, S. A., R. W. Westerfield, and J. Jaffe. 2005. Corporate finance. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Singerman, A. 2018. FE1038. Cost of Production for Processed Oranges in Southwest Florida, 2016/17. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Singerman, A., and M. Burani-Arouca. 2017. FE915. Evolution of citrus disease management programs and their economic implications: The case of Florida's citrus industry. Gainesville: University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Singerman, A., M. Burani-Arouca, and S. H. Futch. 2018. "The Profitability of New Citrus Plantings in Florida in the Era of HLB." HortScience 53(11).

Singerman, A., M. Burani-Arouca, S. H. Futch, and R. Ranieri. 2017. "Harvesting Charges for Florida Citrus, 2016/17." University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. (No longer available online.)

Singerman, A., S. H. Lence, and P. Useche. 2017. "Is Area-wide Pest Management Useful? The Case of Citrus Greening." Applied Economics Policy and Perspectives 39(4): 609–634.

Singerman, A., and P. Useche. 2017. "Florida Citrus Growers' First Impressions on Genetically Modified Trees." AgBioForum, 20(1): 67–83.

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA-NASS). Census of Agriculture. 2002, 2007, 2012.

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA-NASS). 2017. Florida Citrus Statistics 2015–16.

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA-NASS). 2018. Florida Citrus Statistics 2016–17.

Table 1. Internal Rate of Return from Investing in a New Citrus Grove