The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

The family Meloidae, the blister beetles, contains about 2500 species, divided among 120 genera and four subfamilies (Bologna and Pinto 2001). Florida has 26 species, only a small fraction of the total number in the US, but nearly three times that of the West Indies (Selander and Bouseman 1960). Adult beetles are phytophagous, feeding especially on plants in the families Amaranthaceae, Asteraceae, Fabaceae, and Solanaceae. Most adults eat only floral parts, but some, particularly those of Epicauta spp., eat leaves as well.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

A few adults are nocturnal, but most are diurnal or show no distinct diel cycle. Since adults are gregarious and often colorful, they tend to be conspicuous. However, larval blister beetles are seldom seen, except for first instar larvae (triungulins) frequenting flowers or clinging to adult bees. All blister beetle larvae are specialized predators. Larvae of most genera enter the nests of wild bees, where they consume both immature bees and the provisions of one or more nest cells. The larvae of some Meloinae, including most Epicauta spp., prey on the eggs of acridid grasshoppers. A few larvae evidently prey on the eggs of blister beetles (Selander 1981). Of the Florida species, Nemognatha punctulata LeConte (misidentified as Zonitis vittigera (LeConte)) has been found in a nest of a Megachile sp. in Cuba (Scaramuzza 1938) and several members of the genus Epicauta have been associated with the eggpods of Melanoplus spp.

Distribution

Fourteen of the Florida species are limited largely or entirely to the Atlantic and/or Gulf coasts of the US. Twelve species are more or less widely distributed in the central and/or eastern states. Two species occur both in the southeastern US and the West Indies. These two species belong to South and Central American groups and probably reached the continental US from the islands. A third, weaker faunal link with the West Indies is represented by Pseudozonitis longicornis (Horn), which belongs to a group including one West Indian species and two relictual species in east Texas (Enns 1956, Selander and Bouseman 1960). No species is indigenous.

Description

Adults are soft-bodied, long-legged beetles with the head deflexed, fully exposed, and abruptly constricted behind to form an unusually narrow neck, the pronotum is much narrower at the anterior end than the posterior and not carinate (keeled) laterally, the forecoxal cavities open behind, and (in all Florida species) each of the tarsal claws cleft into two blades. Body length generally ranges between 3/4 and 2 cm in the Florida species. Blister beetles (Meloidae) are commonly confused with beetles in the family Oedemeridae (false blister beetles) (Arnett 2008) and the Tenebrionidae subfamily Lagriinae (long-jointed beetles).

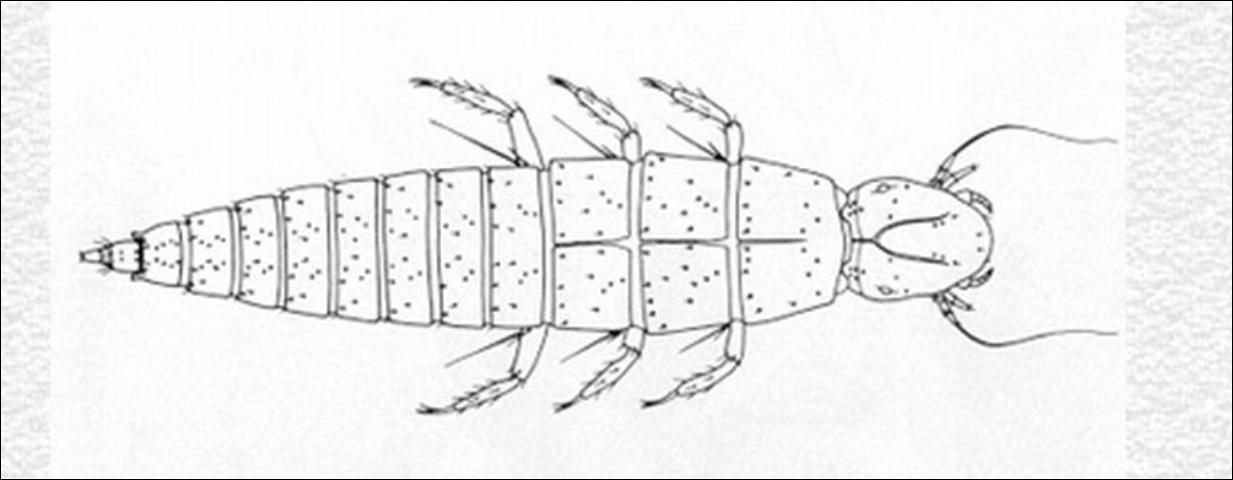

First instar larvae of the family Nemognathinae found in flowers or attached to the hairs of bees are sometimes mistaken for those of Ripiphoridae. In both groups, the body is navicular (boat-shaped) and heavily sclerotized and there is a definite pattern of setation. Nemognathine larvae are distinctive in having one to two (not four to five) stemmata on each side of the head, an ecdysial line on the thorax, and no pulvilli (bladderlike appendages).

Keys to genera for adult beetles (Arnett 1960) and triungulin larvae (MacSwain 1956) are given in references. A key to Epicauta species is in Pinto (1991). Adults of most of the Florida species are described by Enns and Werner (Enns 1956, Werner 1945).

Life Cycle

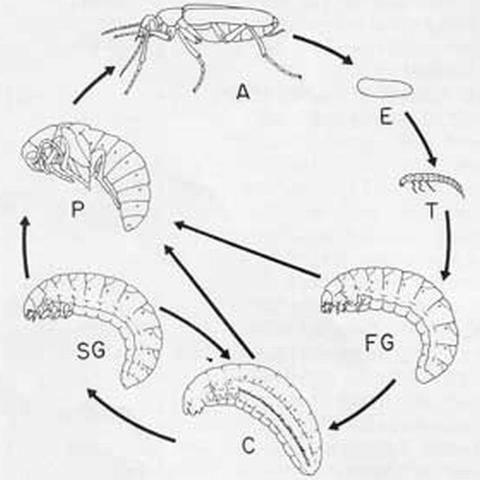

Eggs are laid in masses in the ground or under stones (Meloinae) or on the food plants of adults (Nemognathinae). Larval development is hypermetamorphic, with four distinct phases.

In the first instar or triungulin (T) phase, the larva reaches its feeding site on its own (most Meloinae) or attaches to an adult bee and is carried there (Meloini (not in Florida) and Nemognathinae). After feeding to repletion, the larva, through ecdysis, becomes scarabaeiform and enters a period of rapid growth (first grub phase, FG) that lasts until the end of instar five or six. In some species that prey on bees the FG larva uses only a single cell, while in others it digs into nearby cells and devours their contents. In Meloinae, the fully fed FG larva generally excavates a chamber apart from the feeding site. In instar six or seven, the larva typically becomes heavily sclerotized and immobile (coarctate phase, C). In this phase the musculature undergoes profound degeneration and respiration is reduced to an extremely low level, permitting survival for more than a year, if necessary. When development resumes, the muscles regenerate and, through ecdysis, the larva once again becomes scarabaeiform (second grub phase, SG); at this point it may or may not excavate a pupal chamber. Nemognathinae are unusual in that the SG larva and following pupa and adult are encapsulated by the cast but intact skins of the last instar FG larva and the C larva.

Several alternative developmental pathways have been identified. In response to high temperature, many Epicauta larvae pupate directly from the FG phase or fail to diapause in the C phase; both patterns are conducive to multivoltinism. Rarely, a larva pupates directly from the C phase. Presumably in response to adverse environmental conditions, larvae of several genera of Meloinae can return to the C phase after reaching the SG phase. Most species pass the winter or dry season as coarctate phase larvae, while a few do so as diapausing eggs, triungulin larvae, or adults.

Adults commonly live three months or more. Females typically mate and oviposit periodically throughout their adult lives.

Annotated List of Species in Florida

In the following list, seasonal distribution is not mentioned for species that are active in the adult stage from spring to late summer or early fall. In general, summaries of food plants do not pertain exclusively to Florida. Most distributions and some host data are from Pinto (1991).

Subfamily Meloinae

Epicauta batesii Horn—Eastern and southeastern US, from New Jersey to southern Florida and west to Mississippi. Adult hosts: unknown.

E. cincerea (Forster)—The clematis blister beetle. Eastern North America from Atlantic coast west to the Great Plains, southern Canada south to Texas and the Gulf Coast. Three major color forms: gray tinged with blackish, margined (black with ash gray margins), and black. Adult hosts: Clematis spp.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

E. excavatifrons Maydell—Coastal Mississippi and Alabama, and south to Marion County, Florida. September-October. Adult hosts: recorded from grass.

E. fabricii (LeConte)—The ashgray blister beetle. Eastern North America, from eastern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, less common west of the Mississippi. Florida, from the panhandle south to Highlands County. April–May. Adult hosts: commonly on Fabaceae, including alfalfa, Baptisia, bean, pea, and sweetclover; sometimes attacks potato and glandless cotton. Often taken at lights.

Credit: John L. Capinera, University of Florida

E. floridensis Werner—The "Florida" blister beetle. Eastern US, west to Texas, Oklahoma and Missouri, north to Illinois. Probably statewide in Florida. Adult hosts: Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae), Schrankia (Fabaceae), and (in captivity) Solanum (Solanaceae).

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

E. funebris (=pestifera) Horn—The margined blister beetle. Eastern US, west to Texas and South Dakota and north to Massachusetts. Florida, from the panhandle south to Indian River County. Adult hosts: Many Fabaceae and Solanaceae, including alfalfa, beet, eggplant, potato, soybean, sugar beet, and tomato. Also taken on Amaranthus (Amaranthaceae), and Cynanchum nigrum (L.) (Apocynaceae).

Credit: James Castner, University of Florida

E. heterodera Hom—Southern US, coastal Mississippi to Georgia and south in Florida to Osceola County. Recorded from coastal, southeastern North Carolina. September–November. Adult host: Helenium and other Asteraceae.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

Credit: Lyle J. Buss

E. obesa (Chevrolat)—Southeastern Canada, south through eastern US to Veracruz and Oaxaca, Mexico. In Florida, recorded in Alachua and Orange counties. Adult hosts: Recorded on Clematis (Ranunculaceae) in all regions; and Amaranthus, alfalfa, Tribulus (Zygophyllaceae), and tomato in Oklahoma and Arkansas.

E. pensylvanica (De Geer)—The black blister beetle. Southern Canada from Alberta to the Atlantic Coast south, throughout much of the United States, but not the Pacific Coast states, to northern Mexico. Adult hosts: Wide variety of plants, including many Asteraceae, and such crops as alfalfa, beet, and potato. It is most commonly taken on inflorescences of Solidago.

Credit: John L. Capinera, University of Florida

E. sanguinicollis (LeConte)—Known only from South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. In Florida, recorded in Alachua, Citrus, Sumter, and Brevard counties. Adult hosts: Asteraceae, Schrankia (Fabaceae), and cotton.

E. strigosa (Gyllenhal)—From eastern Texas to the Atlantic and then north along the coast to Massachusetts, probably statewide in Florida. Adult hosts: Principally on cotton, okra, Asteraceae, Opuntia (Cactaceae), Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae), and Vigna (Fabaceae).

Credit: Jeff Hollenbeck

E. tenuis (LeConte)—South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Recorded in Florida from Baker and Volusia counties south to Highlands County. May–June.

E. torsa (LeConte)—Oklahoma and east Texas, east on the Coastal Plain to Georgia and north to Massachusetts; probably statewide in Florida. April–June. Adult hosts: Ilex (Aquifoliaceae), Sapindus (Sapindaceae), and Albizia, Amorpha, and Robinia (Fabaceae).

E. vittata (Fabricius)—The striped blister beetle. Known from southern Ontario and Quebec in Canada and in all states in the US east of longitude 100° except Texas, North Dakota, Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. Represented in Florida where it occurs commonly throughout the state (except in the Keys), extreme southern Georgia and southeastern South Carolina by the "lemniscate" or southeastern coastal race (Adams and Selander 1979). Adult hosts: Wide variety of plants, including Amaranthaceae (Amaranthus), Solanaceae (Solanum) and Fabaceae (Medicago, alfalfa), and such crops as bean, beet, cotton, potato, and tomato. Attracted to lights.

Credit: James Castner, University of Florida

Lytta polita Say—The bronze blister beetle. Georgia border south to Charlotte and Highlands counties. December–June. Has been taken in large numbers at lights.

Credit: James Castner, University of Florida

Pyrota limbalis LeConte—Washington, DC, south to Highlands County, Florida. One record at light.

P. lineata (Olivier)—Northern Florida, including the panhandle, south to Polk County. August-October. Several Asteraceae and Gerardia (Scrophulariaceae).

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

P. mutata (Gemminger)—Northern Florida, including the panhandle, south to Polk County. Cicuta, Daucus, Eryngium, and several other Umbelliferae.

P. sinuata (Olivier)—Coastal Plain from Mississippi to North Carolina, south in Florida to Highlands County. Gerardia (Scrophulariaceae).

Subfamily Nemognathinae

Nemognatha nemorensis Hentz—North Florida, south to Pinellas and Brevard counties. Several Asteraceae, including Bidens, Erigeron, Heterotheca, and, particularly, Rudbeckia.

Credit: Sean McCann

N. piazata Fabricius—Represented in Florida by the nominate race (Mississippi to West Virginia south), which occurs statewide, including the Keys. Cirsium and Tetraognotheca (Asteraceae).

N. punctulata LeConte—Bahama and Cayman islands, Cuba, Jamaica, and the southeastern US. Recorded in Florida only from the Keys and Dade County. Bidens and "thistle" (Asteraceae). Not common.

Credit: Sean McCann

Pseudozonitis longicornis (Horn)—Kansas and east Texas along the Coastal Plain to South Carolina; recorded in Florida from Highlands County south to the Keys. March–July. At lights. Rare.

P. pallida Dillon—Oklahoma and eastern Texas, east to Florida where it extends southward through Dixie and Alachua counties to Hillsborough County. At lights. Not common.

P. schaefferi (Blatchley)—A taxonomically isolated species known only from Florida (Pinellas, St. Johns, and Volusia counties) and Myrtle Beach, South Carolina (Kirk 1969). February–May.

Tetraonyx quadrimaculata (Fabricius)—Trinidad, Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Hispañola, and the US Coastal Plain from northern Florida (Alachua and Putnam counties) to Alabama and North Carolina. Convolvulaceae (Ipomoea) and Fabaceae (Bradburya, Coelosia) in the US and these families and Bignoniaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Verbenaceae in the West Indies. Reported damaging grapefruit flowers in Puerto Rico.

Zonitis cribricollis (LeConte)—Widely distributed in Florida, south to Dade County Achillea, Coreopsis, Helianthus, and Rudbeckia (Asteraceae). Rare.

Zonitis vittigera (LeConte)—Eastern US and southeastern Canada. Represented in Florida, where it occurs south to Highlands County, by the nominate, eastern race. Numerous Asteraceae and Psoralea (Leguminosae).

Medical and Veterinary Importance

Blister beetles received their common name because their hemolymph produces blistering on contact with human skin. Hemolymph is often exuded copiously by reflexive bleeding when an adult beetle is pressed or rubbed against the skin. Blisters are most common on the neck and arms, due to exposure to adult beetles attracted to outdoor lights at night. General handling of adults seldom results in blistering unless the hemolymph contacts the relatively thin skin between the fingers. Unless blistering is extensive, medical treatment beyond first aid is probably not necessary. The blistering on the individual shown in the photograph, while uncomfortable, was not painful. The blisters soon diminished on their own.

The blistering agent is cantharidin, an odorless terpene (exo-1,2-cis-dimethyl-3,6-ep- oxyhexahydro-phthalic anhydride) occurring elsewhere only in beetles of the family Oedemeridae (Arnett 2008). Cantharidin or cantharides (dried, pulverized bodies of adult beetles) were once employed extensively in human and veterinary medicine, primarily as a vesicant and irritant. Cantharidin is still used in the U.S. today, as the active ingredient in a proprietary wart remover (Epstein and Epstein 1960, Kartal Durmazlar et al. 2009). Taken internally or absorbed through the skin, cantharidin is highly toxic to mammals. There is an extensive literature dealing with its reputed aphrodisiacal properties and numerous reports of human poisonings, both accidental and deliberate. Lytta vesicatoria (Linnaeus) is sometimes known as the Eurasian Spanishfly, a source of cantharidin. However, other genera, particularly Mylabris and Epicauta, have been more commonly used. Recorded cantharidin content of adult beetles (by dry weight) ranges from less than 1% to 5.4%. Biological synthesis and function are not fully understood. It is widely assumed that cantharidin confers chemical protection from predators, but there is little evidence for this. In at least some species, females receive large quantities of cantharidin from males during copulation. In any case, females incorporate the material in a coating applied to the eggs.

Cases of fatal poisonings of valuable horses by ingestion of blister beetles trapped in baled alfalfa hay (Kinney et al. 2006, Mackay and Wollenman 1981, Schoeb and Panciera 1979) have revived interest in the pathology of cantharidin toxicosis and led to the development of a highly sensitive technique for detection of the compound (Ray et al. 1979). Research is available to indicate the amount of cantharidin levels present in common species, as well as the estimated number of beetles necessary to provide a lethal dose to horses (Kinney et al. 2006, Sansome 2002).

Poisonings have been traced to several species of blister beetle. Blister beetles pose a potential threat if horse owners use alfalfa as a source of hay. However, alfalfa is not commonly grown in Florida and blister beetles rarely are abundant. Most poisonings in Florida result from importation of alfalfa hay from western states experiencing grasshopper population outbreaks (Capinera, personal communication).

Crop Damage

Several of the Florida blister beetles feed on cultivated plants. Species of Epicauta, particularly the margined blister beetle, E. funebris, and the striped blister beetle, E. vittata, often damage alfalfa, beet, potato, tomato, and other crops by defoliation. Because of the beetles' gregarious behavior, their attacks can be locally catastrophic. In small gardens, it may be sufficient simply to pick the beetles from the plants.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss

Selected References

Adams CL, Selander RB. 1979. The biology of blister beetles of the Vittata Group of the genus Epicauta (Coleoptera, Meloidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 162: 139–266.

Arnett Jr RH. 1960. The Beetles of the United States. Catholic University Press, Washington, D.C.1112 pp.

Arnett JR RH. 2008. False blister beetles, Coleoptera: Oedemeridae. Featured Creatures. EENY-154. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN311

Bologna MA, Pinto JD. 2001. Phylogentic studies of Meloidae(Coleoptera), with emphasis on the evolution of phorsey. Systematic Entomology 26:33–72.

Enns WR. 1956. A revision of the genera Nemognatha, Zonitis, and Pseudozonitis (Coleoptera, Meloidae) in America north of Mexico, with a proposed new genus. University of Kansas Scientific Bulletin 37: 685–909.

Epstein J, Epstein W. 1960. Cantharidin treatment of digital and periungual warts. California Medicine 93 11–12.

Kartal Durmazlar SP, Atacan D, Eskioglu F. 2009. Cantharidin treatment for recalcitrant facial flat warts: A preliminary study. Journal of Dermatological Treatment 20: 114–119.

Kinney KK, Peairs FB, Swinker AM. 2006. Blister beetles in forage crops. Colorado State University Extension. https://extension.colostate.edu/topic-areas/insects/blister-beetles-in-forage-crops-5-524/ (7 May 2020).

Kirk VM. 1969. A list of the beetles of South Carolina. Part I - Northern Coastal Plain. South Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 1033: 1–124.

MacKay RJ, Wollenman P. 1981. An outbreak of blister beetle poisoning in horses in Florida. Florida Veterinary Journal 10: 11–13.

MacSwain JW. 1956. A classification of the First Instar Larvae of the Meloidae (Coleoptera). Entomology Volume 12. University of California Press 182pp.

Pinto JD. 1991. the Taxonomy of North American Epicauta (Coleoptera: Meloidae), with a Revision of the Nominate Subgenus and a Survey of Courtship Behavior. Entomology Volume110. University of California Press. 372pp.

Ray AC, Tamulinas SH, Reagor JC. 1979. High pressure liquid chromatographic determination of cantharidin, using a derivatization method in specimens from animals acutely poisoned by ingestion of blister beetles, Epicauta lemniscata. American Journal Veterinary Research 40: 498–504.

Sansome D. 2002. Blister beetles. Insects in the City. http://citybugs.tamu.edu/FastSheets/Ent-2006.html (no longer available online).

Scaramuzza LC. 1938. Breve nota acerca de dos parásitos de "Megachile sp." (Hymenoptera, Apoidea, Megachilidae). Mem. Soc. Cubana Hist. Nat. 12: 87–88.

Schoeb TR, Panciera RJ. 1979. Pathology of blister beetle (Epicauta) poisoning in horses. Veterinary Pathology 16: 18–31.

Selander RB. 1981. Evidence for a third type of larval prey in blister beetles (Coleoptera: Meloidae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 54: 757–783.

Selander RB, Bouseman JK. 1960. Meloid beetles (Coleoptera) of the West Indies. Proceedings of the U.S. National Musuem 111: 197–226.

Townsend LH. (December 2002). Blister beetles in alfalfa. University of Kentucky Entomology. http://www.ca.uky.edu/entomology/entfacts/ef102.asp (7 May 2020).

Werner FG. 1945. A revision of the genus Epicauta in America north of Mexico (Coleoptera, Meloidae). Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology (Harvard University) 95: 421–517.