The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences.

Introduction

Brown lacewings are small to medium-sized insects (forewing length 3 to 9 mm (~1/8 to 1/3 in) in Florida) that are predaceous both as adults and larvae. They prefer soft-bodied insects such as aphids, mealybugs, and also insect eggs. Because of the longevity of the adults, months in some species; voracious appetites, for example Micromus posticus (Walker) larva consumed an average of 41 aphids during its life (Cutright 1923); and high reproductive capacity, one female Hemerobius humulinus Linnaeus can lay 460 eggs (Smith 1923); they are useful biological control agents. Some species have been used for this purpose, but limited work has been done. In Texas, Sympherobius barberi Banks is mass reared for control of the citrus mealybug (Hart, personal communication). Florida has a small fauna of 10 species in four genera, and this publication provides keys to identification of the adults. There are 58 species in North America.

Distribution

All the Florida species are found in northern Florida, and three of these, Sympherobius occidentalis, Sympherobius gracilis, and Boriomyia fidelis, were recorded for the first time for Florida from Gainesville. Boriomyia speciosa has not been rediscovered in Florida since Carpenter (1940) recorded it from Sanibel Island. Sympherobius amiculus, Soriomyia barberi, and Hemerobius stigma are known as far south as Highlands County, whereas both species of Micromus are found throughout peninsula Florida. Micromus subanticus is also found in the Keys and in the Caribbean. Hemerobius humulinus and Hemerobius stigma are Holaretic, but the former is relatively uncommon in Florida.

Biology

Females lay non-stalked eggs, usually singly or in small groups. There are three larval instars. The 1st instar is active in all species. It can run fast, moving the head from side to side as it moves. In Sympherobius spp. and especially Boriomyia spp., the later instars are relatively immobile. A white cocoon of double structure (outer loose thread, inner compact structure) is constructed in protected areas. Most groups appear to prefer aphids, but Sympherobius spp. may prefer coccid insects (especially mealybugs). Spiders are considered one of the most important natural enemies of lacewings. References on biology for species occurring in Florida are:

- Cutright, 1923: Micromus posticus

- Smith, 1923: Sympherobius amiculus, Hemerobius humulinus, Hemerobius stigma and Micromus posticus

- Smith, 1934: Soriomyia barberi

- MacLeod, 1960: Boriomyia fidelis

Identification

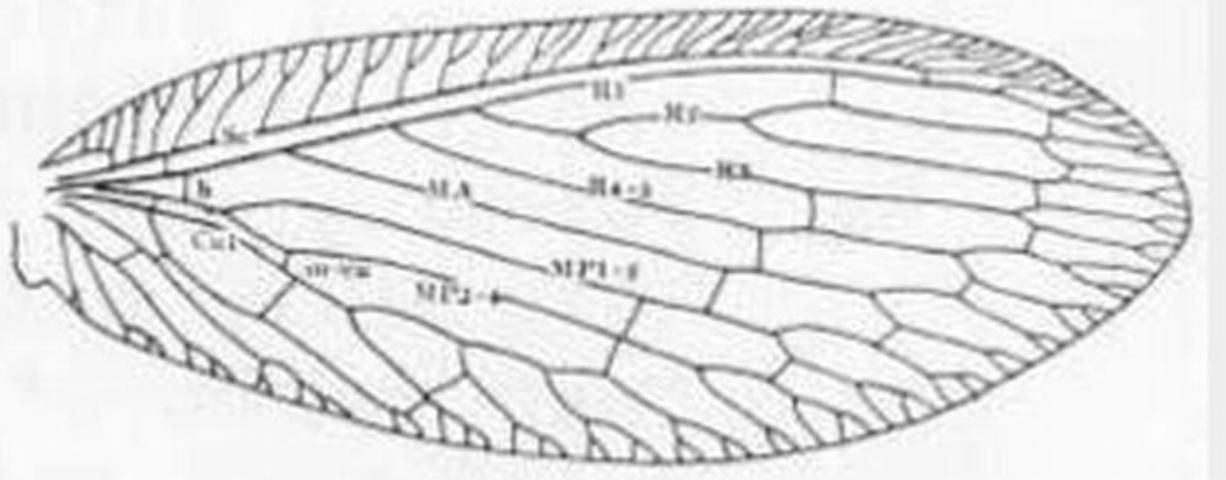

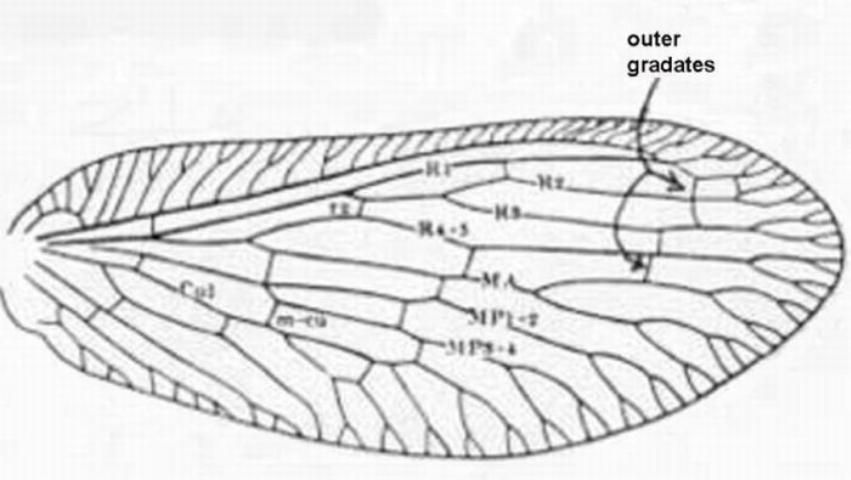

Adults have a wing venation with two or more branches arising directly from the fused stem of R1 + Rs. The wing membrane has microtrichia (contrasted with Chrysopidae), ovipositor not exerted, antenna moniliform, and front legs not raptorial.

Credit: University of Florida

Credit: Ken Gray, Oregon State University

Larvae have jaws that are fairly straight basally and curved apically, mandibles lacking teeth along medial margin, pretarsal claws lacking a trumpet-shaped empodium (a spine or lobelike process) (except 1st instar), and are not trash bearers, in contrast to many statements in older literature (e.g., Comstock 1925, Introduction to Entomology, p. 297).

Detection and Survey

Adults are commonly attracted to lights. Adults and larvae can be found by beating or sweeping plants, especially oaks and pines and plants with high aphid infestations such as alfalfa. Brown lacewings resemble green lacewings (Chrysopidae) but are brownish and are less common. There are 58 North American species. The eggs are laid on plants, but not stalked. The brown lacewing larvae differ from green lacewing larvae in that they do not possess tubercles (a small knoblike or rounded protuberance). Both adults and larvae prey on aphids, other soft-bodied insects and mites.

Credit: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS

Key to Genera and Species of Brown Lacewings of Florida

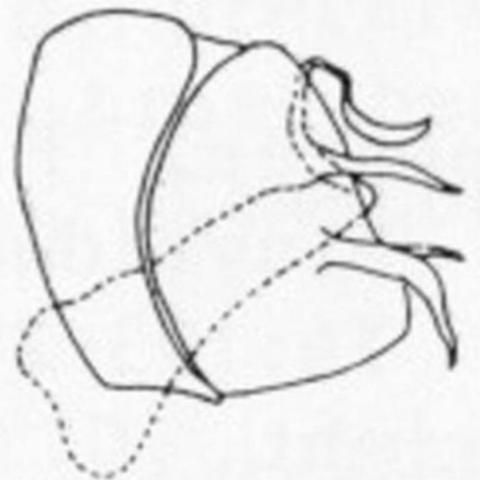

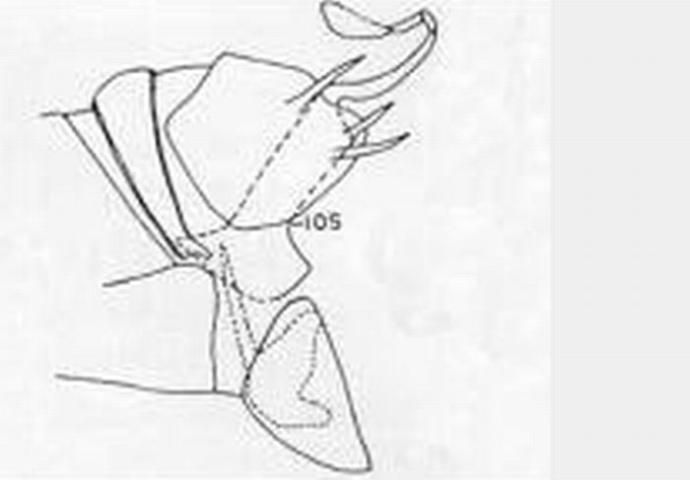

(Wings and male terminalia after Carpenter 1940)

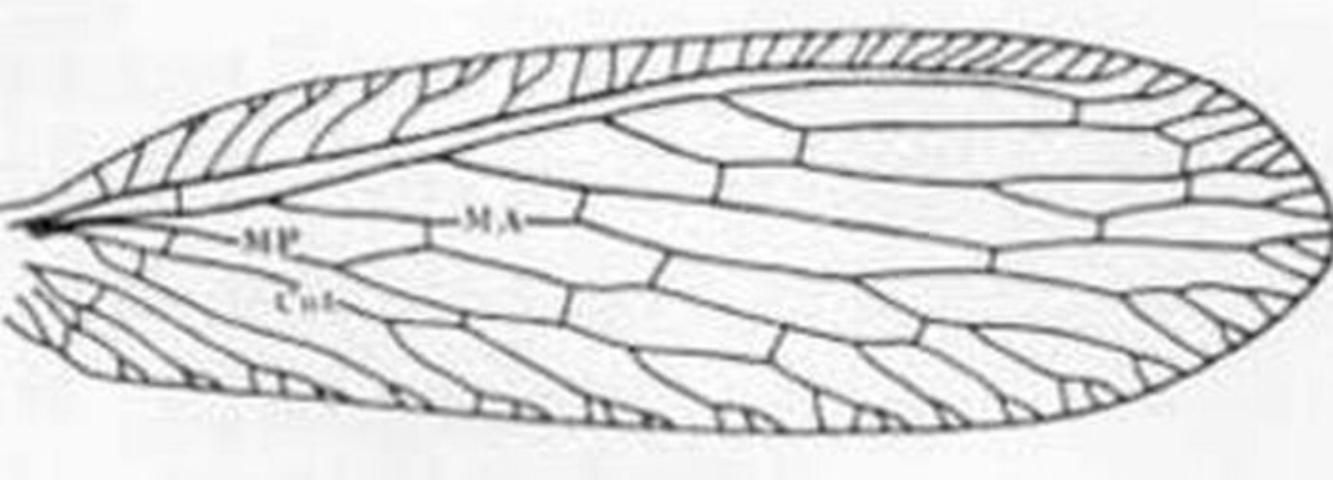

1. Forewing with costal area quite narrow at base, lacking a recurrent humeral vein (Figures 1, 2) . . . . . Micromus Rambur . . . . . 2

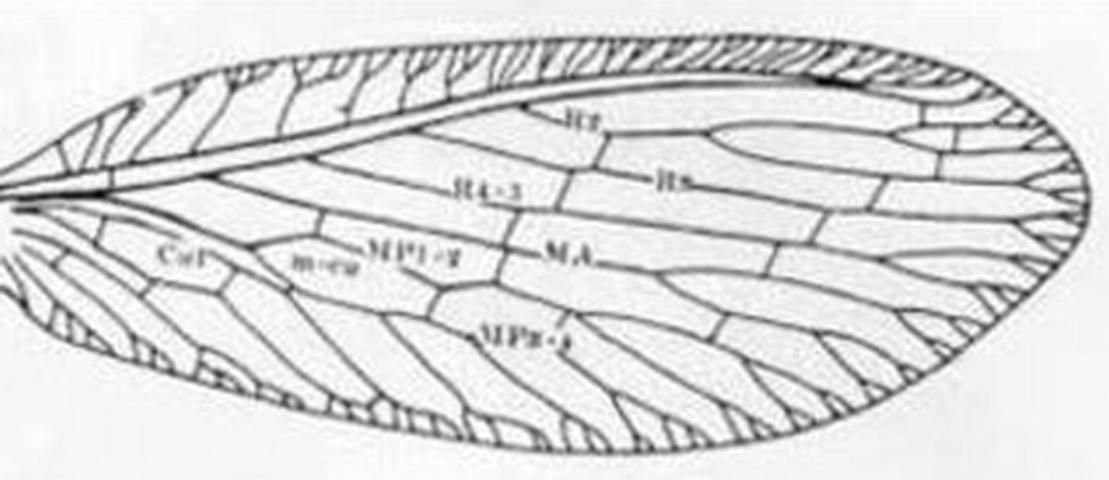

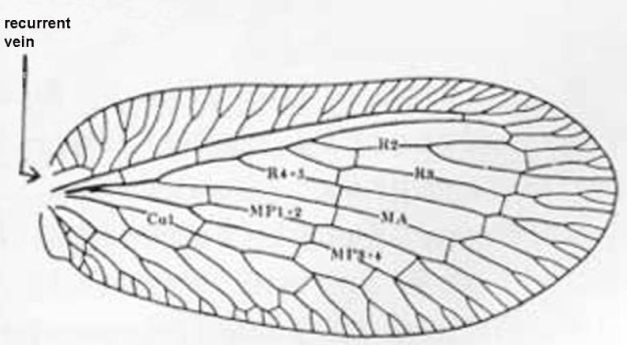

1'. Costal area of forewing much broader basally (Figure 7), often abruptly broadened (Figures 4, 10) and always with a recurrent humeral vein . . . . 3

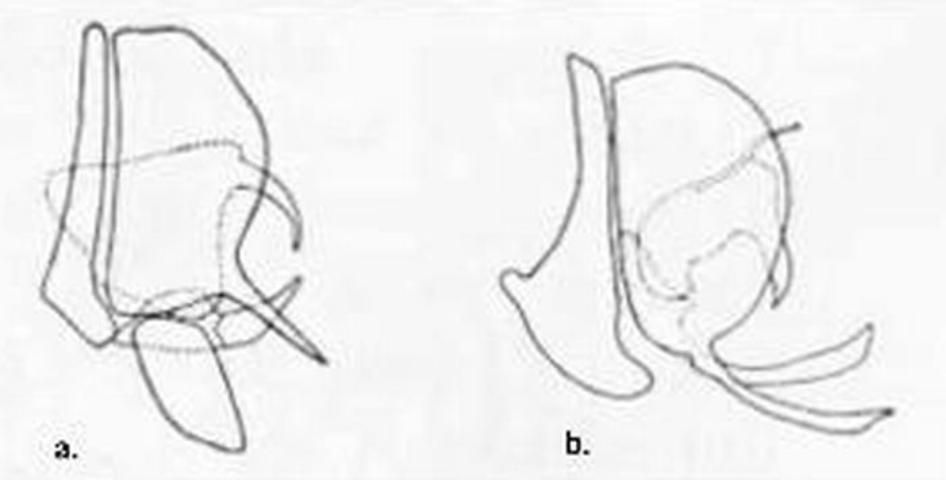

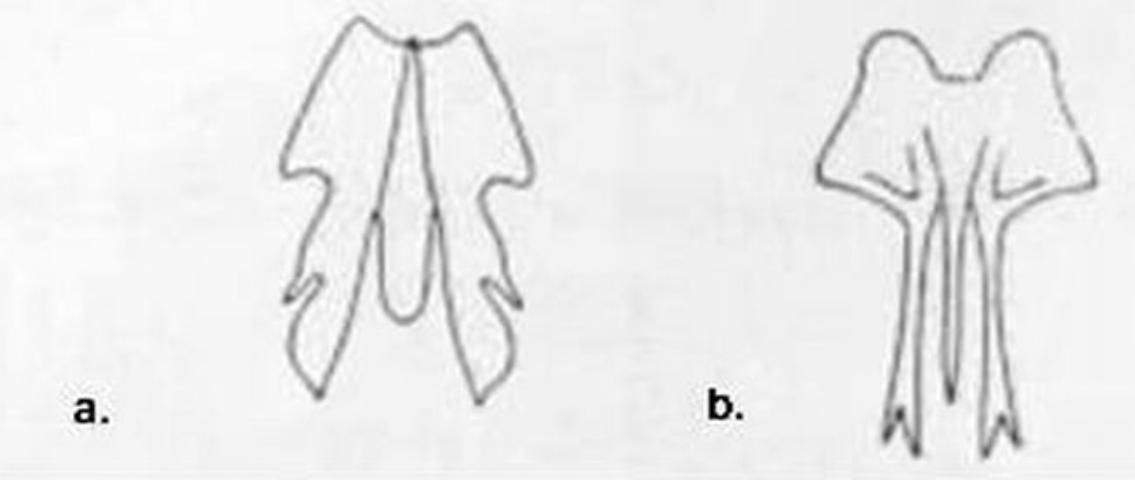

2 (1). Inner gradate veins of forewing much more than their lengths apart (Figure 1); male terminalia as in Figure 3a . . . Micromus subanticus (Walker)

- Observations: M. subanticus is found throughout Florida and also in the Caribbean (Cuba, Dominican Republic, etc.). It occurs in a variety of habitats including both trees and grasses. It is often found in alfalfa fields where both larvae and adults feed on aphids.

2'. Inner gradate crossveins of forewing at most only their lengths apart (Figure 2) ; male terminalia as in Figure 3b . . . Micromus posticus (Walker)

- Observations: In most of the Nearctic Region this is the most common Micromus, but in Florida it is apparently somewhat less common than subanticus and does not occur in the Keys. Its habitats are similar to those of M. subanticus. Smith (1923) and Cutright (1923) published biological observations.

3 (1'). Forewing with three or more branches arising from the fused stem of R1 and Rs distal to separation of MA (Figure 4); maxillary palpus 5-segmented, labial palpus with three segments . . . . . Boriomyia Banks . . . . . 4

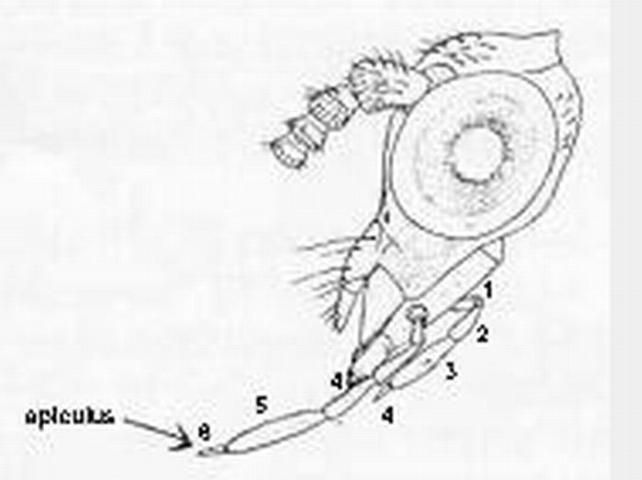

3'. Forewing with fewer than 3 branches arising from R1 + Rs distal to separation of MA (Figure 7), most-basal branch arising from R1 + Rs often stalked with MA (Figure 10); maxillary and labial palpi with a small peg-like apiculus so that they appear 6- and 4-segmented respectively (Figure 16) . . . . . 5

4 (3). Male paramere with lateral process not forked distally (Figure 6a); forewing usually lacking dark brown spots around distal crossveins between branches of Cu (although light brown cloudings of the membrane adjacent to the crossveins may be present), usually with 2 broad transverse light brown bands paralleling the inner and outer series of gradate crossveins . . . . . Boriomyia fidelis (Banks)

- Observations: Recorded here for the first time from Florida (34 specimens from Gainesville, March to September).

4'. Male paramere with lateral process forked distally (Figure 6b); forewing usually with discrete dark brown spots around distal crossveins of Cu and the M-Cu crossvein, pale brown maculations sometimes present elsewhere, especially around the inner and outer series of gradate crossveins . . . . . Boriomyia speciosa (Banks)

- Observations: Carpenter (1940) recorded female specimens from Sanibel Island but we know of no new records from Florida. Few specimens are known so that the constancy of the wing markings must still be verified.

5 (3'). Forewing with five or more outer gradate veins (Figure 7); forewing without crossvein between MP and MA . . . . . Hemerobius Banks . . . . . 6

5'. Forewing with four or fewer outer gradate veins Figure 10); MP and MA connected by crossvein shortly after origin of former (Figure 10) . . . Sympherobius Banks . . . 7

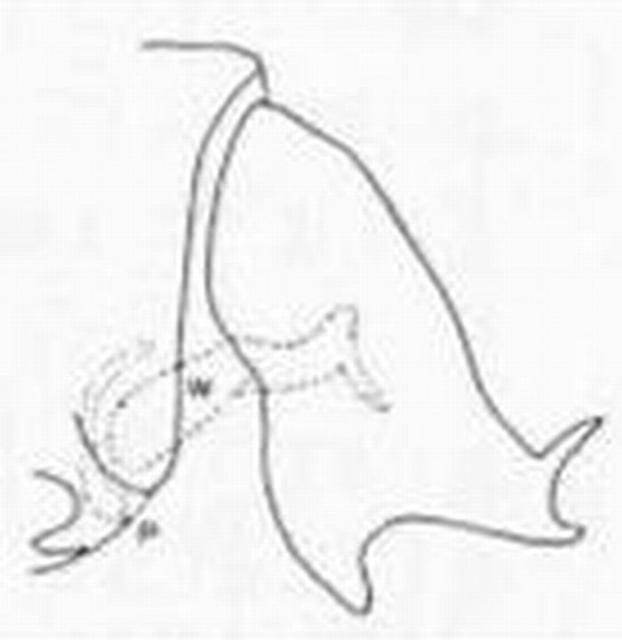

6 (5). Pronotum and mesonotum with broad yellow stripe; upper process of male ectoproct forked distally (Figure 8) . . . . . Hemerobius humulinus Linnaeus

- Observations: This holarctic species appears to be uncommon in Florida. Killington (1937) and Smith (1923) provided biological data.

6'. Pronotum and mesonotum with, at most, a narrow median stripe (this is often absent); mesonotum without defined stripe (Figure 17); upper process of male ectoproct not forked (Figure 9) . . . . . Hemerobius stigma Stephens

- Observations: This is the most common Hemerobius, ranging from the Panhandle to Highlands County. Smith (1923) gave some biological data. Adults hibernate. Tjeder (1960) synonymized stigmaterus Fitch.

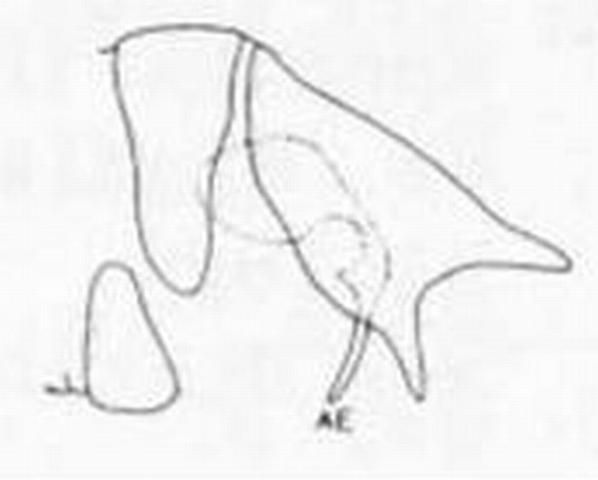

7 (5'). Forewing without radial crossvein; male ectoproct with three processes, none bifurcate; upper process shorter than lower one (Figure 11) . . . . .Sympherobius barberi Banks

- Observations: This is the most widespread U.S. species and has been introduced into Hawaii for biological control. It is being released in Texas or control of citrus mealybug. In Florida there are records from Escambia County to Hillsborough County.

7'. Forewing with radial crossvein (Figure 10, "rc"); male ectoproct either with two processes, or, if three, one is bifurcate or the upper as long as lower one . . . . . 8

8 (7'). Forewing vein Cul forks nearer hindmargin than to crossvein m-cu; male ectoproct with two processes . . . . . Sympherobius occidentalis Fitch

- Observations: This is an uncommon species recorded here from Florida for the first time (two males, Gainesville, March, October). Besides the distinctive wing venation and male ectoproct, the forewing markings are characteristic with veins dark brown and cell pattern similar to S. gracilis, but with the gradates more boldly margined.

8'. Forewing vein Cul forks at or near crossvein m-cu (Figure 10); male ectoproct with three processes . . . . . 9

9 (8'). Most cells of forewing pale in centers and along margins of veins; veins nearly uniformly dark with at most slightly darker points at bases of setae; male ectoproct with lower process bifurcate (Figure 13) . . . . . Sympherobius gracilis Carpenter

- Observations: This uncommon species is recorded here from Florida for the first time (14 specimens from Gainesville, May to July).

9'. Ells of forewing membrane hyaline with irregular gray or brown blotching; veins pale with dark spots at setal bases (especially along Cu and A) and where crossed by membrane maculations; male ectoproct without bifurcate process (Figure 14) . . . . . Sympherobius amiculus (Fitch)

- Observations: This appears to be the most common species in Florida, ranging from the Panhandle south to Highlands County. Smith (1923) described its biology. Both male terminalia and wing maculation are distinctive.

Selected References

Carpenter FM. 1940. A revision of the Nearctic Hemerobiidae, Berothidae. Sisyridae, Polystoechotidae and Dilaridae. Proceedings of the American Academy of the Arts and Science 74: 193–280.

Cutright CR. 1923. Life history of Micromus posticus Walker. Journal of Economic Entomology 16: 448–456.

Dean HA, Hart WG, Ingle S. 1971. Citrus mealybug, a potential problem on Texas grapefruit. Journal of the Rio Grande Horticultural Society 25: 46–53.

Killington F. 1937. A Monograph of the British Neuroptera. Vol. II. The Ray Society, London. p. 1–269.

MacLeod EG. 1960. The immature stages of Boriomyia fidelis (Banks) with taxonomic notes on the affinities of the genus Boriomyia. Psyche 67: 26–40.

Smith RC. 1923. The life histories and stages of some hemerobiids, and allied species. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 16: 129–151.

Smith RC. 1934. Notes on the Neuroptera and Mecoptera of Kansas, with keys to the identification of species. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 7: 120–144.

Tjeder B. 1960. Neuroptera from Newfoundland, Miquelon, and Labrador. Opuscula Ent. 25: 146–149.

Tjeder B. 1961. Neuroptera Planipennia IV. Hemerobiidae. South African Animal Life 8: 296–408.

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry

Credit: Division of Plant Industry