This article is part of a series on smart irrigation controllers. The rest of the series can be found at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/topics/irrigation_systems.

Introduction

Water is essential for the basic growth and maintenance of turfgrass and other landscape plants. When an adequate amount of water is not available to meet plant needs, stress can occur, ultimately leading to reduced quality or even plant death. Irrigation is common in Florida landscapes due to sporadic rainfall and the low water holding capacity of its prevalent sandy soils. This inability of many of Florida soils to hold substantial water can cause plant stress after just a few days without rainfall or irrigation.

Water conservation is a pressing issue in Florida due to increased demands from a growing population. One of the areas with the greatest potential for reducing water consumption is residential outdoor water use, which accounts for half of publicly supplied drinking water in the United States (DeOreo et al., 2016). Most new homes built in Florida are equipped with an automated irrigation system, which includes an irrigation timer to schedule irrigation. These automated irrigation systems have been shown to use 47% more water on average than non-automated systems (e.g., hose and sprinkler), largely due to the tendency to set irrigation timers and not adjust them for varying weather conditions.

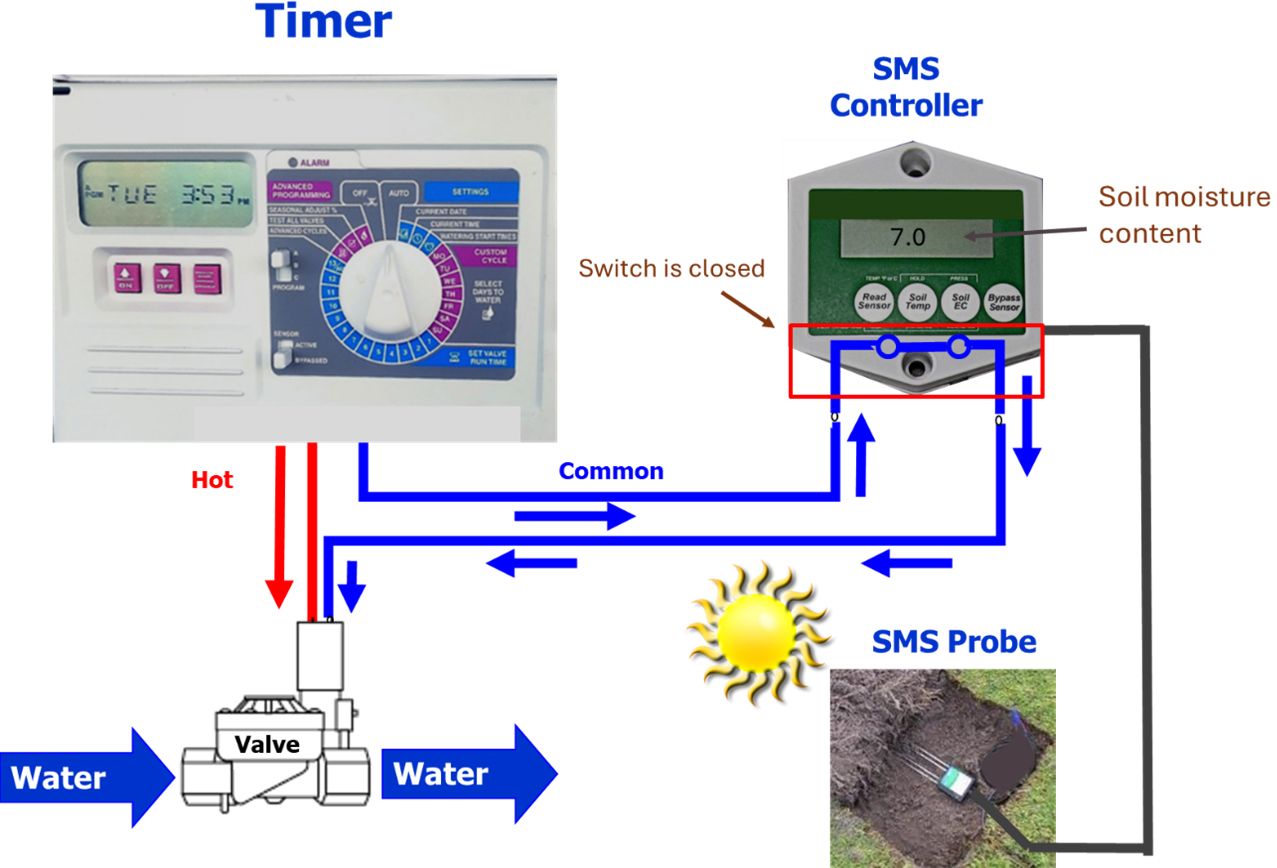

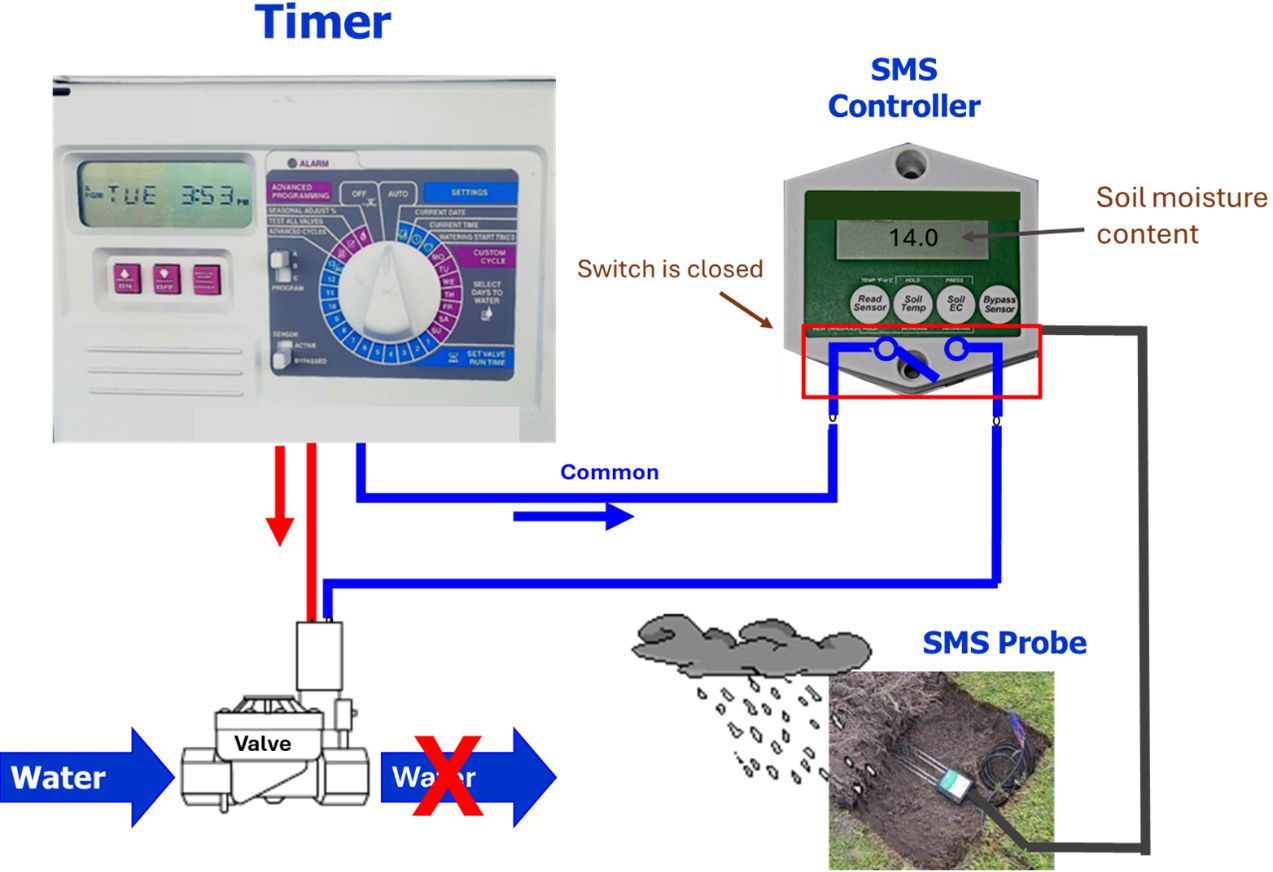

Irrigation control technology that improves water application efficiency is now available. In particular, soil moisture sensor (SMS) systems are add-on devices that connect to automated irrigation system timers and can reduce the number of unnecessary irrigation events. Commercially available SMS systems consist of a probe (or sensor) inserted into the soil and a controller (or interface) where an adjustable soil water content threshold can be set (Figure 1). This Ask IFAS publication is intended for irrigation professionals, homeowners, Extension agents, master gardeners, scientists, and the general public. This document provides basic information about SMS systems when integrated into automatic irrigation systems and how they could reduce irrigation water application.

Credit: Bernard Cardenas UF/IFAS

How Soil Moisture Sensor Systems Work?

Most SMSs are designed to estimate soil volumetric water content based on the dielectric constant (soil bulk permittivity) of the soil, which can be thought of as the soil's ability to transmit electricity. The dielectric constant of the soil rises as its water content increases because the dielectric constant of water is much higher than the other soil components, including air. Thus, measuring the dielectric constant provides a reliable estimate of soil water content. For more information on soil moisture sensors, see Field Devices for Monitoring Soil Water Content, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AE266.

There are two basic types of SMS systems for landscape and small farm irrigation: bypass and on-demand. The most common type is the bypass system, which uses water content information from the probe to either allow or bypass scheduled irrigation cycles on the timer (Figures 2 and 3). The SMS controller has an adjustable soil moisture threshold setting from “dry” to “wet”. The soil moisture content is routinely checked by the sensor and compared to the threshold setpoint, and, if the soil water content exceeds that setting, the irrigation event is bypassed (Figure 3). The soil water content threshold can be manually set by the user or, depending on the SMS brand and model, may be set by an auto-calibration feature (see section “Setting the Soil Moisture Sensor System Threshold” below).

In an on-demand SMS system, there are two threshold settings: a “low” and a “high” threshold. The controller initiates irrigation when the soil water content reaches the low threshold and stops irrigation when it reaches the high threshold. The on-demand SMS controller concept is discussed in What Makes an Irrigation Controller Smart? https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AE442.

Credit: Bernard Cardenas UF/IFAS

Credit: Bernard Cardenas UF/IFAS

Sensor Installation

A single sensor can be used to control the irrigation for many zones (where an irrigation zone is defined by a solenoid valve) or multiple sensors can be used to irrigate individual zones. In the case of one sensor for several zones, the zone that is normally the driest, or most in need of irrigation, is selected for placement of the sensor to ensure adequate irrigation in all zones.

Some general rules for the burial of the soil moisture sensor are:

- Soil in the area of burial should be representative of the entire irrigated area.

- Sensors should be buried in the root zone of the plants to be irrigated, as this is where plants will extract water, and will help ensure adequate turf or landscape quality.

- For turfgrass, the sensor should typically be buried with the center of their sensing section at about three inches deep.

- If otherwise not stated by the manufacturer, sensors should be buried in undisturbed soil, ensuring no air gaps surrounding the sensor.

- Sensors should also be located at least 5 feet from irrigation heads and toward the center of an irrigation zone.

- Sensors should be placed at least 5 feet from the home, property line, or an impervious surface (such as a driveway) and 3 feet from a planted bed area.

- Sensors should not be buried in traffic areas to prevent compaction of the soil around the sensor.

Setting the Soil Moisture Sensor System Threshold

The procedure for determining the irrigation threshold, or setpoint, in the controller is referred as “calibration” by SMS manufacturers. This can be accomplished either manually or automatically. The University of Florida suggests the automatic approach, as it results in a setpoint that is site-specific. Users can adjust this setpoint later if needed.

The initial step in an automatic calibration is to fully saturate the soil where the probe has been installed. This step is essential for establishing the soil's field capacity, which means no additional water will drain below the root zone. To saturate the soil, apply at least 5 gallons of water directly over the installed and connected SMS, using a hose or a bucket.

Important: The soil surrounding the sensor must not receive any water during the 24-hour period following saturation. If there is any irrigation or rainfall during this time, the soil will not reach its field capacity after 24 hours, and the process will need to be restarted once the soil dries out.

After the saturation is completed, the installer should perform the calibration on the SMS controller. Calibration instructions are brand-specific; therefore, the user should consult the manufacturer's manual and follow the provided instructions. After 24 hours, the SMS controller will read the soil moisture content, which should be close to field capacity. At that point, the controller will automatically establish the setpoint, which will range between 50% and 75% of the field capacity, depending on the SMS brand.

Note: Timing related to lawn establishment is an important factor in proper calibration. Establishment periods typically range from 30 to 60 days. The controller and sensor should be calibrated after establishment, as root depth and soil conditions differ between the pre- and post-establishment phases.

Programming the Irrigation Timer with a Soil Moisture Sensor System

Soil moisture sensor systems can help reduce water use on the lawn by bypassing scheduled irrigation events. However, it is essential to ensure that the irrigation schedule is correctly programmed into the irrigation timer to significantly improve water use efficiency.

Before setting the irrigation schedule, it is important to determine when water will be applied and how much should be applied during each irrigation event. In most areas of Florida, the days of the week in which irrigation is allowed is already limited by local water restrictions.

Irrigation run time is the amount of time an irrigation zone stays on to apply the desired amount of water. It is affected by the application rate of the irrigation sprinklers and the time of the year. For more information on setting the irrigation timer properly see Operation of Residential Irrigation Timers, https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AE220, which is also provided as a tool in the Florida Automated Weather Network (FAWN) urban irrigation scheduler (https://fawn.ifas.ufl.edu/tools/urban_irrigation/).

References

DeOreo, W.B., Mayer, P., Dziegielewski, B. and Kiefer, J. 2016. Residential end uses of water, version 2. The Water Research Foundation (WRF): https://www.waterrf.org/research/projects/residential-end-uses-water-version-2.

Dukes, M.D., B. Cardenas, and D.Z. Haman. 2024. Operation of Residential Irrigation Timers. EDIS CIR1421/AE220. Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AE220.

Muñoz-Carpena, R. 2004. Field Devices for Monitoring Soil Water Content. EDIS. Retrieved July 7, 2008, from Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/AE266.